Abstract

The classical model of hematopoiesis has long held that hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) sit at the apex of a developmental hierarchy in which HSCs undergo long-term self-renewal while giving rise to cells of all the blood lineages. In this model, self-renewing HSCs progressively lose the capacity for self-renewal as they transit into short-term self-renewing and multipotent progenitor states, with the first major lineage commitment occurring in multipotent progenitors, thus giving rise to progenitors that initiate the myeloid and lymphoid branches of hematopoiesis. Subsequently, within the myeloid lineage, bipotent megakaryocyte-erythrocyte and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors give rise to unipotent progenitors that ultimately give rise to all mature progeny. However, over the past several years, this developmental scheme has been challenged, with the origin of megakaryocyte precursors being one of the most debated subjects. Recent studies have suggested that megakaryocytes can be generated from multiple pathways and that some differentiation pathways do not require transit through a requisite multipotent or bipotent megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor stage. Indeed, some investigators have argued that HSCs contain a subset of cells with biased megakaryocyte potential, with megakaryocytes directly arising from HSCs under steady-state and stress conditions. In this review, we discuss the evidence supporting these nonclassical megakaryocytic differentiation pathways and consider their relative strengths and weaknesses as well as the technical limitations and potential pitfalls in interpreting these studies. Ultimately, such pitfalls will need to be overcome to provide a comprehensive and definitive understanding of megakaryopoiesis.

Introduction

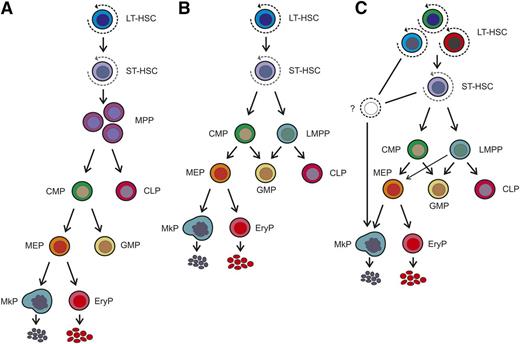

Ever since hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were first identified,1 there has been great interest in developing methods to purify them to better understand the molecular mechanisms regulating their function.2,3 Prospective separation of HSCs became possible with the advent of monoclonal antibodies and fluorescence activating cell sorting, leading to the description of HSC-enriched cells in 1988 by Weissman and colleagues (Spangrude et al4 ). Because similar approaches can also be used to identify committed progenitors, numerous investigators have successfully isolated committed progenitor populations, leading to the development of a hierarchical model of hematopoiesis in which HSCs give rise to increasingly committed progenitors with progressively decreasing self-renewal capacity and restricted lineage potential. In this classical model of hematopoiesis, a major bifurcation occurs between the myeloid and lymphoid branches (Figure 1A), and restricted myeloid progenitors undergo another bifurcation into bipotent granulocyte-macrophage (GM) and megakaryocyte-erythrocyte (MegE) progenitors.5-7 Moreover, unipotent megakaryocytic progenitor cells were placed downstream of bipotent MegE progenitors, suggesting that all megakaryocytes arise from committed precursors that are formed after requisite intermediate states.8,9

Models of the hematopoietic hierarchy. (A) Classical model of the hematopoietic hierarchy with a strict separation between the myeloid and lymphoid branches as the first step in lineage commitment downstream of the hematopoietic stem cell. (B) Alternative model as proposed by Adolfsson et al,32 incorporating the identification of LMPPs. The relationship between the LMPP and the CMP has not yet been resolved, but they are placed at similar positions in the hierarchy based on their lineage potential. (C) Recently proposed model, in which immunophenotypically defined HSC populations or their immediate committed progeny have restricted megakaryocytic potential. In this model, there is heterogeneity within the HSC population with respect to lineage potential, including a megakaryocyte-biased HSC that directly gives rise to megakaryocyte progenitors and bypasses classical intermediate commitment stages, including the CMP and MEP. Note: Nearly all of the studies described were performed in mice, and therefore the model shown should be considered to apply only to the murine hematopoietic system at this time. EryP, erythroid progenitor.

Models of the hematopoietic hierarchy. (A) Classical model of the hematopoietic hierarchy with a strict separation between the myeloid and lymphoid branches as the first step in lineage commitment downstream of the hematopoietic stem cell. (B) Alternative model as proposed by Adolfsson et al,32 incorporating the identification of LMPPs. The relationship between the LMPP and the CMP has not yet been resolved, but they are placed at similar positions in the hierarchy based on their lineage potential. (C) Recently proposed model, in which immunophenotypically defined HSC populations or their immediate committed progeny have restricted megakaryocytic potential. In this model, there is heterogeneity within the HSC population with respect to lineage potential, including a megakaryocyte-biased HSC that directly gives rise to megakaryocyte progenitors and bypasses classical intermediate commitment stages, including the CMP and MEP. Note: Nearly all of the studies described were performed in mice, and therefore the model shown should be considered to apply only to the murine hematopoietic system at this time. EryP, erythroid progenitor.

Although the hierarchical model has been very useful for understanding hematopoiesis, it has become increasingly clear that this model is inadequate for capturing all the complexities of early commitment steps in hematopoiesis and especially in megakaryopoiesis. With advances in the ability to prospectively separate HSCs and committed progenitors and the development of functional and molecular assays to assess the development potential of single cells in vitro and in vivo, a more complex picture of HSC commitment to the megakaryocytic lineage has emerged in which megakaryocytes may arise directly from HSCs as well as from multi-, bi-, and unipotent progenitors. In this review, we discuss the evidence supporting these newer models of megakaryopoiesis.

HSCs and megakaryocytes exhibit numerous similarities

It has long been appreciated that HSCs and megakaryocytes share several features, with the most notable being their shared expression of and dependence on the thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor (MPL) for their maintenance and expansion (reviewed by Huang and Cantor10 ). Indeed, studies of MPL-deficient mice identified defects in the ability of bone marrow to long-term reconstitute the hematopoietic system of irradiated recipients,11 and additional studies have showed that TPO-MPL signaling is important to maintain HSC quiescence.12,13 More recent studies have revealed that HSCs share cell surface receptors with megakaryocytes and their progenitors, including CXCR414,15 and CD150,9,16 and share similarities in gene expression signatures. In fact, a gene expression study comparing 38 states in human hematopoietic differentiation revealed the closest relationship between HSCs and progenitors in the MegE lineage, with these populations forming a separate cluster in an unsupervised analysis.17 Recently, Wilson et al18 performed single-cell functional assays combined with single-cell gene expression analysis and showed that there are cells within different immunophenotypically defined HSC populations that cluster with a subset of progenitor cells, possibly reflecting a megakaryocyte-biased stem cell population because these cells expressed high levels of von Willebrand factor (VWF), among other myeloid lineage-associated genes. Whether or not these individual cells were derived from multipotent, self-renewing HSCs, committed progenitors derived from HSCs or other origins were not addressed functionally, but these studies raised the possibility that HSCs and megakaryocyte progenitors are closer to one another in the hematopoietic developmental hierarchy than previously appreciated.

Perhaps it is not that surprising that HSCs and megakaryocytes are so similar. Given that multicellular organisms must develop strategies for rapidly generating platelets to protect the integrity of the vascular systems, it is possible that the generation of HSCs and generation of platelets are linked. Although this explanation is speculative, co-evolution of immunity and hemostasis can be seen even in invertebrates, in which cellular mediators of hemostasis (so-called “hemocytes”) evolved to protect the host from invading microbes and to prevent blood (ie, hemolymph) loss following injury by triggering coagulation.19,20 In mammals, megakaryocytes and red cells (and macrophages) appear at the same time during development along with the appearance of primitive hematopoiesis in the yolk sac.21,22 It is also noteworthy that the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages share a common embryonic precursor, the hemangioblast,23 with the majority of hemangioblast precursors exhibiting megakaryocyte potential.24 This may explain why many of the factors commonly expressed by megakaryocytes and HSCs (eg, VWF) are also expressed by endothelial cells and hemangioblasts.10 The overlapping and interrelated roles of endothelial cells and megakaryocytes are illustrated in hemostasis, in which platelets function to close disrupted endothelium after injury. In addition, the thrombomodulin-activated protein C pathway, important in anticoagulation,25 is also important for hematopoietic recovery after irradiation.26

Lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors and early loss of megakaryocyte potential

The identification of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs)5,7 and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs)27 resulted in a model of hematopoiesis in which the first lineage commitment step downstream from HSCs occurred at the segregation of the myeloid and lymphoid lineages. In the myeloid branch, CMPs gave rise to 2 more restricted progenitors, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs),5 with MEPs giving rise to erythroid progenitors and unipotent megakaryocytic precursors (Figure 1A).8,9,28

Although the classical model of hematopoiesis is simple in its binary conception of lineage potential, this model of hematopoiesis has been challenged by the identification of new progenitor populations. On the basis of their prior observation that loss of long-term HSC (LT-HSC) self-renewal coincided with the upregulation of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3)29 as well as demonstration that HSCs are enriched in the CD34– fraction of Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells of adult bone marrow,30,31 Adolfsson and colleagues32 evaluated the lineage potential of LSK cells separated on the basis of these cell surface markers. These studies revealed that the LSK cells are composed of multiple populations, including LT-HSCs identified as LSKCD34–Flt3– and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) identified as LSKCD34+Flt3+. Intermediate between these 2 populations is a third population that has gained CD34 expression but still lacks detectable Flt3 expression (LSKCD34+Flt3–) and exhibits a short-term HSC (ST-HSC) phenotype.33 These studies also showed that Flt3 expression identifies cells with varying megakaryocyte potential, with high-Flt3-expressing LSKCD34+ cells lacking significant MegE potential and being unresponsive to TPO, unlike LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs. When single cells from the highest (top 25%) Flt3-expressing LSK cells were assessed in vitro under myeloid-supporting conditions or on OP9 and OP-DL1 stromal cell lines, these cells exhibited granulocyte, monocyte, B-cell, and T-cell potential. When single LSKFlt3+ and LSKFlt3– cells were assessed for megakaryocyte potential by growing them in the presence of TPO in addition to other myeloid-lineage-promoting cytokines, 57% of LSKFlt3– cells produced megakaryocytes compared with only 2% of LSKFlt3+ cells.32 Because megakaryocytes and erythrocytes were thought to share a common progenitor,5 the authors investigated the erythroid potential of LSKFlt3+ cells and showed that these cells also exhibited limited ability to form erythroid progeny at a clonal level. These findings were confirmed in transplantation studies at the population level. In addition, quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) studies showed that LSKFlt3+ cells expressed low levels of genes involved in MegE development (eg, Gata-1, EpoR, Tal-1, Tpo-R) compared with LSKFlt3– cells. In contrast, Pu-1 and G-CSFR levels were comparable, and LSKFlt3+ cells showed increased expression of the early lymphoid gene IL-7Rα. On the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that LSKFlt3+ cells represent lympho-myeloid stem/progenitor cells that possess B-cell, T-cell, and GM potential but lack significant MegE potential, and they named these cells lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs) (Figure 1B). Ultimately, a model of hematopoiesis was formulated in which loss of MegE potential is among the first steps in lineage commitment by HSCs and in which MEPs may potentially directly arise from the ST-HSCs.32 This model was supported by another study that investigated lineage commitment of daughter cells generated in vitro from single HSCs, which suggested that HSC daughter cells may directly differentiate into an MegE progenitor.34 However, these latter studies should be interpreted with care, because differentiation was highly dependent on the culture conditions used. Although it is now clear that the classical model of bifurcated myeloid and lymphoid lineages is an oversimplified view of the lineage potential of the early hematopoietic progenitors, a number of questions remain, including the relationship between LMPPs and CMPs and whether LMPPs represent a heterogeneous population of cells with differences in lineage potential. Indeed, multiplex single-cell PCR revealed that LSKFlt3+ cells co-express IL-7Rα and G-CSFR, but this was only true for approximately 6% of the analyzed cells.32

The conclusions of Adolfsson et al32 were questioned when Forsberg et al35 studied the lineage potential of sorted donor cells derived from β-actin green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice (which express GFP in all nucleated cells and platelets36 ) in vivo instead of using the predominantly in vitro progenitor assays used by Adolfsson et al. In interpreting the results of these studies, it is important to note that Forsberg et al35 used a slightly different sorting strategy that included Thy1.1 to distinguish HSCs from MPPs. Nevertheless, LMPPs (25% brightest Flt3+LSK), were defined by using the same phenotype as Adolfsson et al,32 making it possible to compare these two studies. LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, MPPs, and LMPPs were transplanted, and their lineage potential and kinetics of reconstitution were evaluated. These populations demonstrated an inverse correlation between burst size and maturation state, with only LT-HSCs able to provide long-term multilineage reconstitution, whereas the other populations produced a transient wave of mature cells. Platelet production was observed first on days 7 to 9 after transplantation for all cell populations, and it increased over a 30-day period, but LT-HSCs produced stable platelet engraftment levels after 30 days. After the initial peak of platelet production, ST-HSCs showed a gradual decrease in platelet production over 3 months, whereas MPPs and LMPPs gave rise to platelets for significantly shorter periods (<4 weeks). Forsberg et al35 concluded that the discrepancy in their results and those of Adolfsson et al32 might be the result of differences in the number of transplanted cells and the time at which cell output was assessed. For example, Forsberg et al35 observed robust platelet production from 2500 LMPPs and concluded that LMPPs are capable of thrombopoiesis in vivo, but that higher cell doses of LMPPs than LT-HSCs are required to observe donor-derived platelets because of their lower expansion capacity. However, because these studies were performed with bulk populations, the percentage of sorted LMPPs that possessed platelet potential was not clear. Another group reported that Flt3highLSK cells produce significantly more platelets than Flt3lowLSK cells, with the lowest output in the Flt3highVCAM-1−LSK population, which also showed GM-B-T-lineage restriction.37 By using a different GFP transgenic reporter mouse (under control of Ikaros), Yoshida et al38 confirmed the existence of LMPPs, with GFP+ cells more lineage restricted than GFPlow cells and exhibiting lympho-myeloid potential but no erythroid potential when using in vitro assays. Taken together, these studies strongly supported the existence of an MPP population with lymphoid and GM potential without MegE potential, representing an early step in lineage commitment. However, rather than a sudden loss of MegE potential, it is more likely that there is a gradual decrease in the ability to commit to these lineages, coinciding with an increase in lymphoid priming.39 Thus, in this model, LMPPs mainly give rise to CLPs and GMPs but still exhibit limited MegE potential (Figure 1C). Indeed, the minimal MegE potential of LMPPs coincided with MPPs transitioning from Mplhigh to Mpl– and from Pu.1low to Pu.1high states within the Flt3highLSK population.39,40 Notably, the majority of Mpl+LSK cells were Flt3+ and the majority of Flt3+ cells were Mpl+, suggesting that the differences in megakaryocytic output may be true only for the cells at the far end of the Flt3-Mpl expression spectrum.

Stem cell commitment to megakaryocyte differentiation

It has become increasingly evident that even the most immature LT-HSC pool is functionally heterogeneous.41 In fact, myeloid-biased, lymphoid-biased, and myeloid-lymphoid balanced HSC subsets have been identified,42-45 and such lineage-biased HSCs can be prospectively separated on the basis of differential expression of CD150/SlamF1.46 Previous studies have also reported that CD41 expression marks myeloid-biased adult hematopoietic stem cells and increases with age.47 Unfortunately, none of these studies42-47 evaluated megakaryocyte or erythroid output from these functionally defined HSC subsets.

The identification of LMPPs suggested that a committed MegE-progenitor arises directly from an ST-HSC or early MPP without passing through a requisite CMP intermediate. These studies32,34 also demonstrated an inverse correlation between the degree of differentiation and the time to give rise to mature myelomonocytic and lymphoid cells (ie, faster myeloid cell production from CMPs compared with LT-HSCs). However, this relationship between degree of differentiation and time until detection of mature cells in vivo was not observed for platelets.35 Instead, platelets from all populations with megakaryocyte potential were detected at the same time, suggesting that there might be a short-cut along the differentiation route from HSC to megakaryocyte. Although such an interpretation is reasonable, it should be made with caution because it can be difficult to measure the emergence of cells of the various lineages from small numbers of cells, especially at early time points.

Evidence for a megakaryocyte-biased population of HSCs was provided by the Jacobsen group48 using transgenic mice with a GFP reporter driven by the megakaryocyte-associated VWF gene. Transplanting GFP+ HSCs (LSKCD150+CD48–), the authors showed that VWF-positive HSCs exhibited a distinct lineage-biased reconstitution pattern with a strong platelet bias and contribution to the myeloid lineages but with a very limited (short-term) lymphoid potential. In contrast, VWF-negative HSCs demonstrated a lymphoid-biased reconstitution pattern. Gene expression profiling of VWF-positive and VWF-negative HSCs revealed higher expression of megakaryocyte-lineage genes in VWF-positive HSCs, and a hierarchical relationship between the 2 identified HSC subtypes was established by demonstrating that VWF-positive HSCs can give rise to VWF-negative HSCs (but not the opposite), strongly suggesting that VWF-positive HSCs are at the top of the hematopoietic hierarchy.48

Additional evidence for a megakaryocyte-based subset of HSCs (Figure 1C) was reported by our group49 as well as Waskow’s,50 with highly purified LT-HSCs (LSKCD34–CD150+) exhibiting differences in lineage output based on differences in c-Kit cell surface expression. HSCs with high c-Kit expression were less quiescent compared with c-Kitint/low HSCs, and they exhibited reduced long-term lymphomyeloid reconstitution potential. In addition, early platelet production after transplantation was largely restricted to the highest c-Kit–expressing HSCs, although at later time points c-Kithigh and c-Kitint cells exhibited similar frequencies of myeloid and lymphoid cells. In vitro clonal assays showed that a significant percentage of single c-Kithigh HSCs possess megakaryocytic potential, and this potential correlated with increased expression of genes known to promote megakaryocyte development.49 Notably, no evidence was found for differential expression of CD41 on c-Kitint vs c-Kithigh HSCs.49,50 Interestingly, when both c-Kithigh and c-Kitint HSCs were placed into liquid culture conditions, both populations gave rise to cells with classical CMP and MEP immunophenotypes, but c-Kithigh cells gave rise to these cells with faster kinetics. Thus, these studies suggest that even immunophenotypic HSCs that rapidly give rise to megakaryocytes transit through the same development states as other HSCs. This raises the possibility that rapid in vivo platelet generation from immunophenotypic HSCs may arise from megakaryocytic progenitors generated from a more rapidly executed, but typical, megakaryocyte differentiation program. Unfortunately, it is difficult to compare the results of our group and Waskow’s group with those of Jacobsen et al48 because these studies used different strategies to sort HSCs, and the expression of VWF in c-Kithigh vs c-Kitint/low cells was not reported. It is likely that c-Kithigh and VWF-positive HSCs are not entirely overlapping, because in contrast to c-Kithigh cells, VWF-positive HSCs were reported to exhibit stable long-term reconstitution potential. It will be important to understand the relationship between these populations.

By performing single-cell transplantations of CD34– LSK cells from red fluorescent protein–positive transgenic mice, Yamamoto et al51 clonally traced donor-derived cells within all blood lineages. These studies demonstrated the presence of a unipotent megakaryocyte repopulating progenitor (MkRP). In addition, among the different types of progenitors identified among HSC daughter cells, only repopulating progenitors of the myeloid lineages, and not the lymphoid lineages, were found, suggesting that commitment to the myeloid lineage occurs before commitment to the lymphoid lineage. Consistent with the observations by Forsberg et al,35 platelet reconstitution was always detected first among all the lineages in transplanted mice, including those transplanted with a single HSC. In addition, paired daughter cell analyses followed by single-cell transplants demonstrated that in some cases the daughters consisted of one LT-HSC and one MkRP, indicating that LT-HSCs can differentiate into a megakaryocyte-restricted progenitor within 1 cell division. In fact, in cases in which the LT-HSC daughter cell pairs both reconstituted recipients, 7% gave rise to an LT-HSC and MkRP, and 11% gave rise to an ST-HSC and MkRP.51

Direct transition from an HSC to a unipotent megakaryocyte progenitor seems to be in conflict with studies indicating that all hematopoietic lineages develop from Flt3+ progenitors.52,53 In studies supporting a direct transition, a dual-color reporter mouse model was used that expressed red fluorescent protein in all cells except those expressing Flt3, in which Cre-mediated excision resulted in the expression of GFP. This irreversible excision resulted in all progeny of GFP+ cells to express GFP, even if those cells did not express Flt3 (GFP) themselves. The authors concluded that in steady-state hematopoiesis as well as upon transplantation, all blood lineages (including platelets) transit through an Flt3+ state. Because a 100% color switch was never observed within the myeloid lineages, the development of platelets directly from an Flt3– HSC could not be entirely excluded. Although imperfect floxing efficiency could explain the incomplete color switch, as suggested by the authors, no significant difference in the labeling of platelets vs myelomonocytes was observed, which would be expected if Flt3+ MPPs gave rise to myelomonocytes but not platelets. The data would also be compatible with a model in which a direct HSC-to-megakaryocyte transition occurs with a very transient upregulation of Flt3 without a detectable intermediate step. In this scenario, the cells developed through the pathway proposed by the Nakauchi group (Yamamoto et al51 ) would also be detected by the tracing system used by Forsberg et al.35

More recent studies have also provided support for a model in which HSCs rapidly commit to unipotent megakaryocytic progenitors not derived from bipotent MegE-committed progenitors (Figure 1C). Transplanted CD41+LSK cells differentiated into all myeloid and lymphoid cell types in vivo and gave rise to unipotent megakaryocytic progenitors (MkPs), mature megakaryocytes, and platelets in vitro and in vivo much more efficiently than Flt3+CD41–LSK cells.28 In addition, by using single-cell qPCR and flow cytometry, the authors were able to show that unipotent MkPs and a fraction of CD41+LSK cells, but not bipotent megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (biEMP), showed similarities in messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and TPO-induced signaling. Interestingly, a subset of CD41+LSK cells expressed CD42b after 5-fluorouracil challenge, with 90% of CD41+CD42b+LSK cells exhibiting restricted megakaryocytic potential in single-cell cultures and predominant platelet production after transplantation. The authors interpreted these results to show that CD41+CD42b+LSK cells are immediate progeny of megakaryocyte-platelet–biased stem cell–repopulating cells, but not of biEMP. Unfortunately, such studies were not performed after purifying LSK cells by using markers such as CD150, CD34, or c-Kit, and lineage and self-renewal capacity were not assessed in vivo. Such studies would have allowed a more detailed understanding of the relationships between CD41+LSK cells and previously defined LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and LMPP populations. In addition, the relationship between the stress-induced CD41+CD42b+ MkP and other previously identified MkP populations were not explored. However, a recent study54 demonstrated the presence of a subset of megakaryocyte-committed cells within the immunophenotypically defined HSC compartment that becomes activated upon inflammatory stress to efficiently replenish platelets. During homeostasis, these so called stem-like megakaryocyte-committed progenitors (SL-MkPs) were shown to be mainly quiescent but primed to megakaryocyte commitment because transcripts that encoded several megakaryocyte-associated proteins were actively translated in response to inflammation, resulting in the generation of mature megakaryocytes. SL-MkPs could be identified by their high CD41 expression upon inflammatory stimulation, and they represented a subpopulation of VWF+ HSCs, suggesting a model in which VWF+ HSCs preferentially give rise to SL-MkPs.

Megakaryocytes in the hematopoietic stem cell niche

The importance of the niche in regulating HSC function is well appreciated, and a role for megakaryocytes in the niche has been suggested.55-58 Two recent studies59,60 have demonstrated that megakaryocytes likely contribute to the HSC niche because in vivo megakaryocyte ablation results in a loss of HSC quiescence. Because HSCs are proximal to megakaryocytes in the bone marrow and because no changes were observed in other cellular niche components, these effects appear to be the result of direct effects of megakaryocytes on HSCs.59 This effect seems to be mediated in part by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), because TGF-β1 injection rescued HSC quiescence in megakaryocyte-depleted mice, and genetic deletion of Tgfb1 in megakaryocytes induced effects similar to megakaryocyte ablation.60 This phenotype may also be mediated in part by CXCL4 (a factor known to regulate HSC quiescence) produced by megakaryocytes, because administering CXCL4 to megakaryocyte-depleted mice partially rescued the HSC defect.59 Taken together, these data demonstrate a direct role for megakaryocytes in HSC regulation and raise the possibility that megakaryocytes provide direct feedback to HSCs, thereby controlling their own replenishment. Indeed, under stress conditions (eg, after chemotherapeutic treatment), the role of megakaryocytes might switch to promoting HSC proliferation and expansion, possibly by FGF1 secretion.60 It would be interesting to determine whether this feedback mechanism promotes megakaryocyte-platelet production by regulating multipotent HSCs or preferentially stimulates megakaryocyte-biased HSCs. In the latter case, one might hypothesize that platelet-biased HSCs could occupy distinct niches in which megakaryocytes play an important supportive role.

Developing a unified model of early megakaryopoiesis

Recent studies using clonal in vitro assays and in vivo clonal tracking analyses have identified cells within immunophenotypically defined HSCs or their immediate committed progeny that possess restricted megakaryocytic potential. These studies have resulted in a new model of megakaryopoiesis and a reconceptualization of the hematopoietic hierarchy (Figure 1C). In this model, HSCs are heterogeneous with respect to lineage potential and include a megakaryocyte-biased HSC (either LT or ST) that directly gives rise to megakaryocyte progenitors, bypassing the classical intermediate commitment stages. Meanwhile, megakaryocyte commitment is also possible through the classical pathway, including commitment to a bipotent MEP. In this new model, LMPPs mainly give rise to CLPs and GMPs and their progeny but can still commit to the MegE lineage (thinner arrow in Figure 1C). But how accurate is this model? In our opinion, a number of technical pitfalls and conceptual concerns must be addressed before a definitive model of megakaryopoiesis can be formulated.

At least 2 biases or pitfalls have strongly influenced the development of newer models of megakaryopoiesis. The first is common to nearly all studies, namely a reliance on cell surface immunophenotypes to identify candidate HSCs and committed progenitor populations. Given the HSC field’s pursuit to identify more highly-enriched HSC populations based on cell surface antigens,2,3 perhaps it is not surprising that this has led investigators to assume that cell populations with immunophenotypes similar to those of HSCs should be composed of cells with similar function. However, this assumption may not hold true for megakaryocytic progenitors, as exemplified by the presence of so-called “megakaryocyte-biased HSCs.”45,46,48 This potential bias can be addressed by identifying additional markers to prospectively separate distinct HSC subsets, such as those described for myeloid- and lymphoid-biased HSCs.46

The second bias or pitfall is an assumption shared by many of the studies, that HSCs must either divide (eg, paired daughter assays51 ) or alter their cell surface phenotypes during lineage commitment. A priori there is no reason to assume that either must be true, and definitive positive experimental evidence for either requirement is lacking. It is possible that changes in the expression of mRNA or protein encoding lineage commitment factors may occur in shorter time periods than those required for HSC or progenitor cell division or alterations in cell surface phenotypes, which could explain why HSCs might seem to commit directly to the megakaryocytic lineage. This phenomenon could also explain the observation that subsets of HSCs express megakaryocyte-associated genes. If this is true, then fluorescent reporters driven by megakaryocyte-associated gene promoters such as VWF may not necessarily mark the most immature HSC but rather an HSC that has acquired megakaryocytic potential.48 Ultimately, to resolve this issue, more sensitive techniques to identify the earliest steps in megakaryocyte commitment are required. For example, a methodology that allows real-time, sensitive measurement of the megakaryocyte-associated mRNA expression may significantly improve the ability to track megakaryocytic lineage commitment within HSC-enriched populations.

Although single-cell transplant assays have helped to characterize the diversity of outcomes for HSC-enriched populations, the inability to prospectively separate these subsets makes it difficult to determine whether the variable lineage potential is a result of contamination by committed progenitors within the immunophenotypically defined HSC pool or a result of intrinsic lineage bias of single HSCs themselves. The identification of markers that allow separation of clonally distinct, immunophenotypically defined HSCs and characterization of their hierarchical relationships could help distinguish between these possibilities. Thus, increased efforts to identify such markers are warranted.

It is important to note that many of the unresolved questions with respect to early megakaryocytic commitment remain because of differences in the cell populations evaluated (ie, using different immunophenotypes to identify HSCs) and the nature of the assays used (eg, in vitro vs in vivo; clonal vs population based). Ultimately, it will be important for investigators to use similar strategies, whether they use identical cell surface phenotypes or genetic reporters to identify HSCs, to resolve differences in experimental results and interpretations. Even if these factors are controlled for, investigators will still have to contend with the pitfalls of in vitro and transplantation assays used to functionally evaluate hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. In vitro assays, by their very nature, likely do not accurately reflect normal physiologic conditions, and in vivo transplantation assays are typically performed in irradiated animals, which can induce significant changes in hematopoietic output.61 Thus, it will be important to develop methods for studying endogenous hematopoietic differentiation at the clonal level in defined HSC and progenitor cell populations.

Clonal assays will remain the preferred method for evaluating engraftment and lineage outcomes of candidate HSC and progenitor populations because they can quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate differences in megakaryocyte potential in heterogeneous cell populations. However, these assays may be difficult to interpret because platelet production may be transient and below the limit of detection when assessing in vivo output from a limited number of candidate HSCs or progenitor cells. This is an important concern because platelets are frequently not evaluated until at least 2 weeks after transplant, at which time non–self-renewing megakaryocytic progenitors likely are no longer present and no longer give rise to platelets.35 Because some immunophenotypically defined HSCs may be able to commit to the megakaryocyte lineage almost immediately, it will be important to assess commitment to the megakaryocytic lineage at earlier time points during differentiation assays, even before cell division. This point is highlighted by our own data showing that although c-Kithigh HSCs give rise more rapidly to megakaryoctyes and platelets in vivo and in vitro, both c-Kithigh and c-Kitlow HSCs give rise to immunophenotypically defined MEPs, although c-Kithigh HSCs do so with faster kinetics.49 These data suggest that these HSCs may transit through similar potential progenitor stages, but more quickly. This issue could theoretically be addressed by evaluating the immunophenotype of engrafted donor hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells after single HSC transplants, even preceding the first wave of platelet entry into the peripheral blood. However, this approach would be very challenging because current methods likely would not be sufficiently sensitive to detect such small numbers of progeny from single-cell transplants.

Finally, it is important to note that most of the studies that have rigorously assessed the earliest steps in megakaryocyte lineage commitment were conducted in the mouse system. Although a putative human LMPP was identified using a combination of in vitro culture and xenotransplantation assays,62 whether human megakaryopoiesis includes megakaryocyte-biased HSC in addition to bipotent and unipotent megakaryocytic progenitors has yet to be investigated. One of the gene expression studies that indicated a close relationship between HSCs and MegE progenitors was performed in human cord blood and peripheral blood, suggesting that the observations in the murine system might also be true for humans,17 but at present, the concept of lineage-biased HSCs has not been confirmed in the human system.2 We look forward to future studies that assess whether human and mouse hematopoiesis exhibits similar properties with respect to these early steps in megakaryopoiesis, including the development of experimental systems that allow in vivo clonal tracking of single human HSCs and committed progenitors in the xenotransplantation setting.

Authorship

Contribution: C.M.W. and C.Y.P. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

Correspondence: Christopher Y. Park, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, Box 20, New York, NY, 10065; e-mail: parkc@mskcc.org.