Key Points

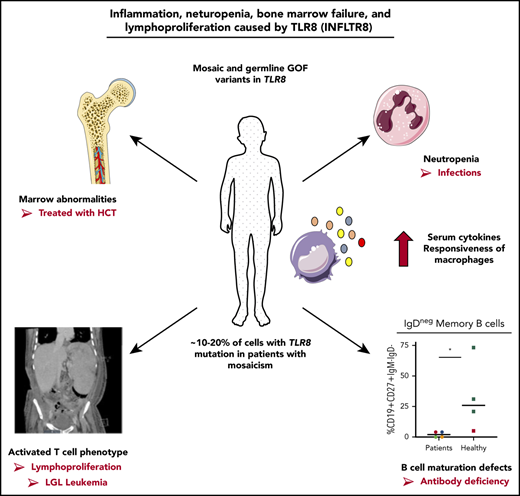

Mosaic and germline gain-of-function variants in TLR8 cause neutropenia, antibody deficiency, lymphoproliferation, and bone marrow failure.

TLR8 gain of function leads to an inflammatory environment with activated T cells and abnormalities in B-cell differentiation.

Visual Abstract

Some images in the graphical abstract were adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), provided by Les Laboratoires Servier. They are available for reuse under the CC-BY 3.0 Unported license.

Some images in the graphical abstract were adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), provided by Les Laboratoires Servier. They are available for reuse under the CC-BY 3.0 Unported license.

Abstract

Inborn errors of immunity (IEI) are a genetically heterogeneous group of disorders with a broad clinical spectrum. Identification of molecular and functional bases of these disorders is important for diagnosis, treatment, and an understanding of the human immune response. We identified 6 unrelated males with neutropenia, infections, lymphoproliferation, humoral immune defects, and in some cases bone marrow failure associated with 3 different variants in the X-linked gene TLR8, encoding the endosomal Toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8). Interestingly, 5 patients had somatic variants in TLR8 with <30% mosaicism, suggesting a dominant mechanism responsible for the clinical phenotype. Mosaicism was also detected in skin-derived fibroblasts in 3 patients, demonstrating that mutations were not limited to the hematopoietic compartment. All patients had refractory chronic neutropenia, and 3 patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. All variants conferred gain of function to TLR8 protein, and immune phenotyping demonstrated a proinflammatory phenotype with activated T cells and elevated serum cytokines associated with impaired B-cell maturation. Differentiation of myeloid cells from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells demonstrated increased responsiveness to TLR8. Together, these findings demonstrate that gain-of-function variants in TLR8 lead to a novel childhood-onset IEI with lymphoproliferation, neutropenia, infectious susceptibility, B- and T-cell defects, and in some cases, bone marrow failure. Somatic mosaicism is a prominent molecular mechanism of this new disease.

Introduction

Inborn errors of immunity (IEI) are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders affecting the immune system with multiple clinical manifestations, including infection, autoimmunity, autoinflammation, bone marrow failure, malignancy, and atopy.1,2 Genomic investigation of rare patients with IEI has revealed a spectrum of genetic inheritance and mechanisms of disease, including loss-of-function and gain-of-function variants, sometimes in the same gene with overlapping or divergent phenotypes.3-5 While most IEIs are associated with germline defects, postzygotic mutational events leading to somatic mosaicism can also cause disease; for example, somatic mutation in hematopoietic stem cells can cause autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome.6 The overall number of patients with IEIs due to postzygotic somatic mosaicism was thought to be relatively low based on rare case reports. However, recent investigation using targeted sequencing of 128 families suspected to have specific IEIs but without an identified germline variant found that ∼15% of patients had mosaic variants in the known targeted IEI genes.7 The recent identification of somatic mutations in UBA1 in the hematopoietic cells of men with adult-onset autoinflammatory disease highlights the importance of investigating nongermline genetic variants in IEIs.8 However, somatic mosaicism is generally overlooked as a cause of IEI and monogenic disease, particularly with regards to disease discovery. The reasons for this may include challenges in detecting low-frequency variants and the need to perform genetic testing on the tissue or cell type carrying the variant.

We identified 6 unrelated males with severe infections, neutropenia, humoral abnormalities, and bone marrow failure consistent with an IEI. Sequencing of peripheral blood DNA samples identified novel missense variants in the TLR8 gene, with 5 patients having genetic mosaicism. TLR8 is located on the short arm of chromosome X (Xp22.2) and encodes Toll-like receptor protein 8 (TLR8), an endosomal receptor that senses microbial single-stranded RNA degradation products and serves to alert the immune response to the presence of viral and bacterial infection.9,10 TLR8 is primarily expressed by neutrophils and monocytes. We investigated the mechanism whereby identified variants altered the function of the encoded TLR8 protein and the immune response associated with the clinical phenotype of patients. Findings identified increased activity of TLR8 and downstream inflammatory signals associated with human disease.

Methods

Patients and genetic testing

Written and informed consent was obtained for all participants at Washington University or the National Institutes of Health. Some patients were identified through GeneMatcher.11 These studies were approved by the institutional review boards of the authors’ institutions. Exome sequencing was performed using whole-blood DNA as a research or clinical test. To confirm genetic variants and determine allele frequency, droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) (Bio-Rad) was performed with DNA and/or complementary DNA (cDNA) samples from the indicated tissue. ddPCR included ddPCR SuperMix for Probes (no dUTP) (Bio-Rad), reference probe (HEX dye), and probes specific for TLR8 c.1295C>T or TLR8 c.1482C>A variants (FAM dyes, custom design, Bio-Rad), nuclease-free water with 25 ng DNA or cDNA. All ddPCR assays were analyzed using the QX200 Droplet reader and Quantasoft software version 1.7.4.

Flow cytometry

Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and analysis of phosphorylated p65 Ser536 (NF-κB) were performed using standard flow cytometry–based assays. Detailed methodology is provided in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Serum cytokine analysis

Serum cytokines were measured using a multianalyte (13-plex) (Luminex assay kit; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) by the Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Programs at Washington University. Analytes assayed included tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-18 (IL-18), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), BAFF, sIL2Rα, IL-12/23p40, CXCL10, IL-10, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, IL1-β, and MCP-1. IL-18 binding protein levels were measured by a previously defined method.12 Levels of soluble forms of Fas ligand were quantitated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA).

Transfection studies in TLR8-deficient NF-κB reporter cell line

Expression plasmids with P432L, F494L, G572D, and D543A were generated as described in supplemental Methods. Human HEK Blue Null1 NF-κB reporter cells (InvivoGen), which lack expression of TLR7 and TLR8, were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, normocin (50 μg/mL), blasticidin (10 μg/mL), and Zeocin (100 μg/mL) (InvivoGen). NF-κB transcriptional activity was measured by quantifying secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) by QUANTI-BLUE assay (InvivoGen) in reporter cells transiently transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutant TLR8 following stimulation. TLR ligands/agonists used in these studies included TL8-506 (TLR8 agonist), CLO75 (TLR8/TLR7 agonist), R848 (resiquimod, a TLR7/TLR8 agonist), or CL264 (TLR7 agonist) (all from InvivoGen). Specificity of TL8-506 for TLR8 was demonstrated in HEK cells expressing human TLR7, which did not respond to TL8-506 stimulation (supplemental Figure 2B). Similarly, cells expressing TLR8 but lacking TLR7 did not respond to stimulation with CL264 (supplemental Figure 2F). For transfection experiments, briefly, 500 ng (or indicated concentration) WT or mutant TLR8 plasmid was transiently transfected into reporter cells (Lipofectamine; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and 48 hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with the indicated doses of TLR agonist followed by quantification of SEAP in the supernatant as a readout of NF-κB activity. Fold change in SEAP activity was calculated by normalizing data to untransfected wells without TLR8 stimulation. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), where a P value < .05 was considered significant.

Fibroblast and iPSC line generation

Skin-punch biopsies were obtained from patients P1, P2, P3, and P5 after written informed consent and approval from local institutional review boards at Washington University, Nemours Alfred I. DuPont Hospital for Children, or Vanderbilt University. Primary fibroblasts lines from patients were generated by the Genome Engineering and iPSC Center at Washington University in St. Louis. Fibroblasts from 2 patients (P2 and P3) were reprogrammed to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by the Genome Engineering and iPSC Center using the Cytotune 2.0 reprogramming kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Karyotype (G-banding) was performed and confirmed 46XY karyotype. The STEMdiff Hematopoietic Kit (05310, STEMCELL Technologies, Inc.) was used to differentiate iPSCs into CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs). Detailed methodology is provided in supplemental Methods.

Generation of iPSCs or modified CD34-derived neutrophils and macrophages

To differentiate neutrophils, CRISPR-modified CD34s (details for generation in supplemental Methods) or iPSC-derived CD34s were maintained in STEMspan media containing stem cell factor (100 ng/mL, Stem Cell Technologies) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF; 10 ng/mL, R&D Systems) and were differentiated by a slight modification of a previously described protocol.13 Cells were pelleted by centrifugation on day 14, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with CD45, CD66b (BD Optibuild) for the defining neutrophil population (CD45+/CD66b+) and used for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Neutrophil differentiation was further confirmed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining following cytospin centrifugation on slides at 500 rpm for 8 minutes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Macrophages were differentiated from iPSC-derived CD34s with Myeloid Expansion Supplement II (Stem Cell Technologies). Macrophage differentiation was confirmed on day 14 by flow cytometry as CD45+CD14+ (BD Biosciences) and by H&E staining.

Additional methods in online supplement

Additional detailed methodology for protein modeling, protein expression by western analysis, mass cytometry, and IFN signature studies may be found in supplemental Methods.

Results

Clinical phenotype

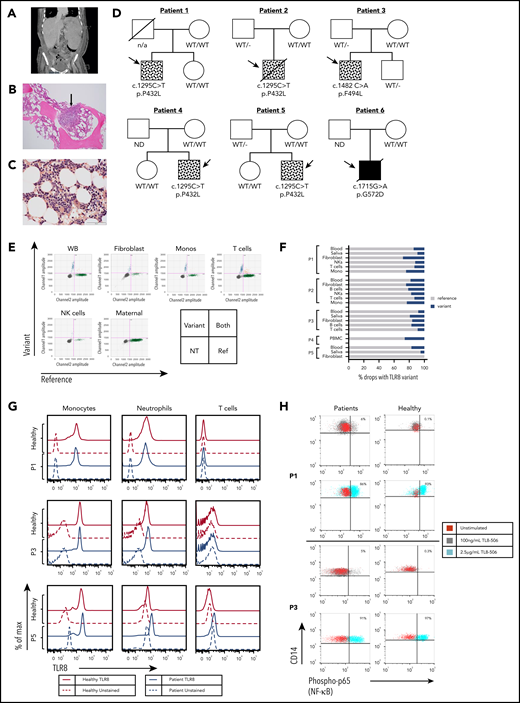

All patients (P1-P6) presented with infections leading to diagnosis of neutropenia (Table 1). Clinical case summaries for each patient may be found in supplemental Methods. Two patients presented in their first year of life (P2 and P6). One patient (P5) had a history of refractory immune thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly at 5 years of age prior to onset of neutropenia at age 14 years. Absolute neutrophil counts were 0 or very low at diagnosis (range, 0-284 cells/µL; supplemental Table 1). All patients had evidence of lymphoproliferation, including lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly (Table 1 and Figure 1A). Two patients had positive antineutrophil antibodies (supplemental Table 2).

Patients have mosaic and germline variants in TLR8 with normal expression of TLR8 protein and enhanced responsiveness to TLR8 stimulation. (A) Abdominal computed tomography scan from P1 showing marked splenomegaly. (B) H&E staining of bone marrow biopsy specimen (P3) showing hypocellularity for age with lymphohistiocytic aggregate (arrow). (C) Leder staining demonstrating myeloid hypoplasia (P3). (D) Family pedigrees of the 6 patients with variants in TLR8. Symbols with dots indicate mosaicism, and the solid black box indicates a germline variant in P6 (ND, not done). (E) ddPCR of patient DNA showing droplets with TLR8 variant p.P432L (upper left), WT TLR8 (lower right), both templates (upper right), or no TLR8 template (lower left) for P1 and the mother. Monos, monocytes; NK, natural killer; WB, whole blood, NT, no TLR8 template. (F) Percentage of droplets with variant or WT sequence in DNA or cDNA from whole blood or PBMCs, saliva, fibroblast lines, and/or sorted cell populations. (G) Intracellular TLR8 expression by flow cytometry in cells from age-matched healthy controls (solid red lines) and patients (P1, P3, and P5, solid blue lines). Similar expression of TLR8 was observed in patient monocytes and neutrophils. CD3+ T cells did not express TLR8. Red dashed line and blue dashed line indicates unstained control in healthy controls and patients respectively. (H) Expression of phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in monocytes (CD14+) from patients (P1 and P3) and healthy age-matched male controls stimulated with indicated doses of TLR8 agonist TL8-506. A small percentage (5% to 6%) of patient monocytes responded to the lower dose (100 ng/mL) of the stimulant. Healthy cells responded at the highest dose of TLR8 stimulation. There was no statistical difference between the patient cells and healthy cells with respect to their response at the highest dose of stimulation.

Patients have mosaic and germline variants in TLR8 with normal expression of TLR8 protein and enhanced responsiveness to TLR8 stimulation. (A) Abdominal computed tomography scan from P1 showing marked splenomegaly. (B) H&E staining of bone marrow biopsy specimen (P3) showing hypocellularity for age with lymphohistiocytic aggregate (arrow). (C) Leder staining demonstrating myeloid hypoplasia (P3). (D) Family pedigrees of the 6 patients with variants in TLR8. Symbols with dots indicate mosaicism, and the solid black box indicates a germline variant in P6 (ND, not done). (E) ddPCR of patient DNA showing droplets with TLR8 variant p.P432L (upper left), WT TLR8 (lower right), both templates (upper right), or no TLR8 template (lower left) for P1 and the mother. Monos, monocytes; NK, natural killer; WB, whole blood, NT, no TLR8 template. (F) Percentage of droplets with variant or WT sequence in DNA or cDNA from whole blood or PBMCs, saliva, fibroblast lines, and/or sorted cell populations. (G) Intracellular TLR8 expression by flow cytometry in cells from age-matched healthy controls (solid red lines) and patients (P1, P3, and P5, solid blue lines). Similar expression of TLR8 was observed in patient monocytes and neutrophils. CD3+ T cells did not express TLR8. Red dashed line and blue dashed line indicates unstained control in healthy controls and patients respectively. (H) Expression of phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in monocytes (CD14+) from patients (P1 and P3) and healthy age-matched male controls stimulated with indicated doses of TLR8 agonist TL8-506. A small percentage (5% to 6%) of patient monocytes responded to the lower dose (100 ng/mL) of the stimulant. Healthy cells responded at the highest dose of TLR8 stimulation. There was no statistical difference between the patient cells and healthy cells with respect to their response at the highest dose of stimulation.

With the exception of P1, who responded to G-CSF therapy and prednisolone, patients had a poor response to therapeutic or high doses of G-CSF. Five patients received immunoglobulin replacement therapy due to low serum immunoglobulin G (IgG), recurrent infections, and/or low B-cell numbers (Table 1). All patients received immunosuppressive therapies that included corticosteroids. Other medications used in >1 patient included sirolimus and rituximab (clinical case summaries, supplemental Methods). Bone marrow biopsy findings varied and included hypocellularity and lymphohistiocytic or lymphoid aggregates (Table 1 and Figure 1B-C; supplemental Table 1). A T-cell clonality test was performed on the bone marrow of 4 patients, and 2 patients had oligoclonality with dominant T-cell clones in the marrow by T-cell receptor γ rearrangement studies (P1 and P4; Table 1). Three patients (P2, P4, and P5) underwent hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). P2 had bone marrow findings of absent neutrophils with normal myeloblasts and a prolonged period (>9 months) of absent peripheral blood neutrophils prior to allogeneic HCT from a mismatched unrelated donor. He failed to engraft with his first transplant and was retransplanted several months later but died at day +172 due to renal failure and vasoplegia (clinical case summaries, supplemental Methods). P4 was diagnosed with evolving T-cell large granular lymphocytic (T-LGL) leukemia and underwent haploidentical donor HCT, subsequently requiring donor T-cell infusions due to relapse of neutropenia with loss of donor chimerism. P5 had a hypocellular bone marrow with leukopenia and thrombocytopenia refractory to treatment prior to a matched sibling HCT. P6 died at 8 years of age due to overwhelming fungal infections and bone marrow failure.

Genetic investigation

Exome sequencing identified TLR8 gene variants in all patients, either on initial review or by targeted review of the TLR8 gene evaluating for low-level mosaicism (Figure 1D). Five patients (P1-P5) had mosaic TLR8 variants; 4 patients (P1, P2, P4, and P5) shared the same variant (c.1295 C>T; p.P432L), while the fifth patient (P3) harbored a different mosaic variant (c.1482 C>A, p.F494L). The final patient (P6) had a de novo germline hemizygous variant in TLR8 (c.1715 G>A, p.G572D). None of the variants were present in the gnomAD database,14 and all were predicted to be deleterious by Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score (supplemental Table 3). No other known disease-causing variants relevant to clinical phenotypes were identified. To determine the frequency of mosaicism and its origin, ddPCR was performed using DNA and cDNA from different cell lineages and tissues including whole blood, PBMCs, purified immune subsets, saliva and/or skin fibroblast lines in patients with mosaic variants (Figure 1E-F). All patients had <30% mosaicism, with similar allelic frequencies across different cell types, suggesting the mutational event may have occurred at an early stage of embryonic development. One patient (P5) did not carry the mutated allele in a skin fibroblast line. Analysis of lung tissue of P2 post-HCT at a time when he had 100% donor chimerism revealed the presence of the variant in the DNA, but not RNA (not shown), consistent with the presence of genetic mosaicism in lung tissue rather than the presence of donor immune cells expressing TLR8 transcript.

Functional consequences of TLR8 variants

Monocytes and neutrophils from patients expressed TLR8 protein (Figure 1G). Following ligand binding, TLR8 signaling activates NF-κB to upregulate a proinflammatory transcriptional signal. Stimulation of peripheral blood monocytes with a low dose of the TLR8 agonist TL8-506 led to the activation of a small percentage of monocytes (5% to 6%) in patients with mosaic variants, as measured by phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) (Figure 1H), suggesting that the observed TLR8 variants may lower the activation threshold to ligand in primary cells.

Based on mosaicism conferring disease and enhanced activation of patient cells, we hypothesized that the variants may confer increased function to the encoded protein. The TLR8 dimer undergoes a rigid body rotational and hinge motion upon activation (supplemental Figure 2A).15 Residues affected by the mosaic variants, P432 and F494, contact each other in one monomer and, after TLR8 activation, come into close contact with the same residues from the other subunit (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2A). Similarly, G572, the location of the germline variant, is solvent exposed in the inactive dimer but is in close proximity to R375 in the other subunit in the activated dimer. In both cases, patient amino acid substitutions would be predicted to kinetically or thermodynamically stabilize activated TLR8 homodimers through hydrophobic (P432L and F494L) or charged (G572D) interactions.

Functional studies demonstrate gain of function of TLR8. (A) Analysis of residues altered by TLR8 variants show that positions P432 and F494 contact the symmetric positions in the other subunit of the active ligand-bound dimer. G572D in the ligand-binding state is predicted to enter into a hydrophobic pocket and interact with R375. (B-C) NF-κB reporter cells (HEK Blue Null1 cells) that do not express endogenous TLR8 were transfected with WT TLR8, patient TLR8 variants (encoding p.P432L, p.F494L, p.G572D), or a loss-of-function (LOF) TLR8 variant (encoding p.D543A) and stimulated with the indicated doses of the TLR8-specific agonist TL8-506 (B) or the TLR8/TLR7 agonist CLO75 (C) for 24 hours. Mosaic and germline TLR8 variants lead to gain of function in TLR8 activity as measured by NF-κB transcriptional activity. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation of biological replicates and representative of 8 independent experiments (TL8-506) or 3 independent experiments (CLO75). **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001 by 2-way ANOVA test.

Functional studies demonstrate gain of function of TLR8. (A) Analysis of residues altered by TLR8 variants show that positions P432 and F494 contact the symmetric positions in the other subunit of the active ligand-bound dimer. G572D in the ligand-binding state is predicted to enter into a hydrophobic pocket and interact with R375. (B-C) NF-κB reporter cells (HEK Blue Null1 cells) that do not express endogenous TLR8 were transfected with WT TLR8, patient TLR8 variants (encoding p.P432L, p.F494L, p.G572D), or a loss-of-function (LOF) TLR8 variant (encoding p.D543A) and stimulated with the indicated doses of the TLR8-specific agonist TL8-506 (B) or the TLR8/TLR7 agonist CLO75 (C) for 24 hours. Mosaic and germline TLR8 variants lead to gain of function in TLR8 activity as measured by NF-κB transcriptional activity. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation of biological replicates and representative of 8 independent experiments (TL8-506) or 3 independent experiments (CLO75). **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001 by 2-way ANOVA test.

A cell line lacking TLR7 and TLR8 (HEK Blue Null1) was transfected with reference (WT) and mutant TLR8 constructs (p.P432L, p.F494L, and p.G572D), as well as a previously reported loss-of-function mutant, p.D543A15 (supplemental Figure 2C). Overexpression of WT or variant TLR8 did not lead to constitutive signaling (Figure 2B-C). Following stimulation with the TLR8-specific chemical ligand TL8-506, the 3 putative disease-causing constructs led to an increased NF-κB activity compared with WT or loss-of-function constructs (Figure 2B). The gain-of-function response was independent of the concentration of plasmid (supplemental Figure 2D) and was also present in the presence of WT TLR8 (supplemental Figure 2E) and when stimulated with a TLR8/TLR7 ligand (CLO75) (Figure 2C). When TLR8 variants were expressed in a reporter cell line also expressing TLR7, similar enhanced responses to TLR8 ligand, but not TLR7 ligand, were observed, supporting specificity of the enhanced responsiveness due to patient variants (supplemental Figure 2F). Together, these findings support gain of function of TLR8 due to the identified genetic variants.

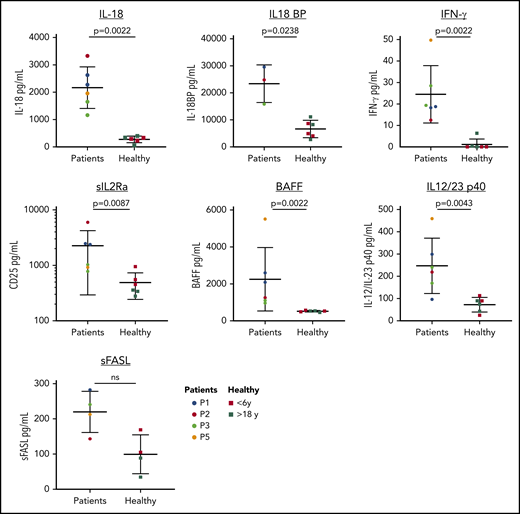

Immunologic features in patients with gain-of-function TLR8

Immunologic laboratory features of the patients were variable, likely due to differences in disease state of patients (Figure 3). Several patients had evidence of T-cell dysregulation, with inverse CD4:CD8 ratio, skewed naive to memory ratio of CD4+ T cells, and elevated CD8+ CD45RA+ CCR7− effector memory T cells . Patients also had increased double-negative T cells (supplemental Table 2), which is seen in patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome but also reflective of immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, and a lymphoproliferative state.16,17 Consistent with hypogammaglobulinemia, all patients had reduced class-switch memory B cells. Further characterization of B-cell subsets in 2 patients identified reduced frequency of CD24hiCD38hi transitional B cells, CCR6+ naive B cells, and a reduced expression of CD21 on naive B cells relative to healthy controls (supplemental Figure 3B), suggesting an impairment in activation of naive B cells and maturation of B cells. One patient had a high percentage of CD21lo/− B cells (supplemental Figure 3B), a subset of naive B cells that is elevated in patients with autoimmune diseases and common variable immune deficiency, and is associated with splenomegaly and cytopenias.18-20 Serum cytokine analysis revealed significantly elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-18, IFN-γ, IL12/23p40, and IL2Rα (Figure 4; supplemental Figure 3A). The B-cell survival factor BAFF was also elevated in patients, consistent with the observed defects in mature B cells.21 Three patients had elevated soluble Fas ligand levels (>200 pg/mL), a biomarker of lymphoproliferative disorders and a mediator of neutropenia in chronic idiopathic neutropenia and large granular lymphocytic leukemia.22-24 Monocyte subset analysis showed a reduced frequency of nonclassical CD14loCD16+ monocytes compared with age-matched controls (supplemental Figure 3C). TLR8 signaling upregulates type I IFNs.9 While 3 patients with mosaic variants had an increased IFN signature in their peripheral blood compared with healthy controls, this was lower than patients with primary disorders of type I IFN production (supplemental Figure 4), suggesting it may not be the major driver of disease in our patients.25 Bone marrow samples from P1 and P5 were examined by mass cytometry for intracellular cytokines and other markers of inflammation, and findings in P1 correlated with that patient’s highly activated T-cell immune phenotype and hyperinflammatory cytokine environment detected in the serum (supplemental Figures 5-7). Together, these studies demonstrate the presence of an inflammatory signal in patients with an activated T-cell phenotype and defects in B-cell maturation and suggest the possibility of an inflammatory environment in the bone marrow.

Immunological findings in TLR8 gain-of-function patients. (A) Representative flow plots of T and B cells immunophenotyping showing a skewed ratio of CD4+ T cells expressing CD45RA or CD45RO (RA:RO ratio) and reduced class-switch memory B cells in a representative patient. (B) Quantitation of CD4:CD8 ratio, CD45RA:CD45RO ratio, percentage of effector memory T cells re-expressing CD45RA (CD45RA+ CCR7− effector memory T cells [TEMRAs]), and percentage of memory B cells and class-switch memory B cells relative to age-matched healthy male controls. In contrast to healthy controls, patients had a significantly reduced percentage of class-switch memory B cells. Young healthy male controls (<6 years) are indicated in red and young adult healthy male controls in green. Horizontal line indicates the median; a Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical evaluation. Findings that are statistically significant are denoted by an asterisk (*P ≤ .05).

Immunological findings in TLR8 gain-of-function patients. (A) Representative flow plots of T and B cells immunophenotyping showing a skewed ratio of CD4+ T cells expressing CD45RA or CD45RO (RA:RO ratio) and reduced class-switch memory B cells in a representative patient. (B) Quantitation of CD4:CD8 ratio, CD45RA:CD45RO ratio, percentage of effector memory T cells re-expressing CD45RA (CD45RA+ CCR7− effector memory T cells [TEMRAs]), and percentage of memory B cells and class-switch memory B cells relative to age-matched healthy male controls. In contrast to healthy controls, patients had a significantly reduced percentage of class-switch memory B cells. Young healthy male controls (<6 years) are indicated in red and young adult healthy male controls in green. Horizontal line indicates the median; a Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical evaluation. Findings that are statistically significant are denoted by an asterisk (*P ≤ .05).

Elevated serum cytokines in patients. Patients have increased levels of IL-18, IL-18 binding protein (BP), IFN-γ, sCD25, BAFF, and IL12/23p40. No statistical difference was observed between the levels of Fas ligand in the patient and healthy group; however, 3 patients had elevated levels of Fas ligand (>200 pg/mL). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation; a Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical evaluation. Multiple samples collected >6 months apart were assayed for P1 and P3. Young healthy male controls (<6 years) are indicated in red and young adult healthy controls in green. L, ligand; ns, not significant; S, soluble.

Elevated serum cytokines in patients. Patients have increased levels of IL-18, IL-18 binding protein (BP), IFN-γ, sCD25, BAFF, and IL12/23p40. No statistical difference was observed between the levels of Fas ligand in the patient and healthy group; however, 3 patients had elevated levels of Fas ligand (>200 pg/mL). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation; a Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical evaluation. Multiple samples collected >6 months apart were assayed for P1 and P3. Young healthy male controls (<6 years) are indicated in red and young adult healthy controls in green. L, ligand; ns, not significant; S, soluble.

Myeloid differentiation of patient-derived iPSCs and gene-edited CD34+ cells

Skin fibroblast lines from P2 and P3 with either the p.P432L or p.F494L mosaic defects were reprogrammed into iPSCs that were then single-cell cloned to generate lines with WT or variant TLR8. Following multiple (≥5) passages, cell lines appeared clonal based on the presence of WT or variant TLR8 DNA (supplemental Figure 8A). Hematopoietic precursor cells were differentiated from patient-derived iPSC lines and cultured with G-CSF to generate neutrophils (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 8B-C). HPCs derived from iPSC-p.P432L had 100% variant TLR8 DNA allele frequency. Following neutrophil differentiation, there was an emergence of a small population (∼30%) of neutrophils with WT TLR8 DNA sequence detected by both ddPCR and Sanger sequencing, potentially due to outgrowth of previously undetectable WT iPSCs through selective advantage or somatic reversion. However, it is unclear whether this WT DNA was efficiently transcribed and expressed, since WT cDNA from the same samples was not detected by PCR (supplemental Figure 8D-E). Stimulation of iPSC-derived neutrophils from WT or variant TLR8 with a TLR8 ligand demonstrated increased NF-κB signaling in samples with TLR8 variants compared with neutrophils with WT TLR8, demonstrating gain of function in primary relevant cells (Figure 5A). Similar findings were observed in neutrophils from healthy donor hematopoietic progenitors (CD34+ cells) genetically engineered to express the p.P432L TLR8 variant (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 9A-C). Hematopoietic precursor cells derived from patient P2 iPSCs were also differentiated into macrophages. Similar to neutrophils, macrophages with variant TLR8 (p.P432L) demonstrated increased NF-κB signaling in response to TLR8 stimulation (Figure 5C). As with results from neutrophil assays, undifferentiated iPSC-p.P432L and derived CD34+ HPCs did not have detectable WT TLR8 sequence; however, following differentiation into macrophages, there was again an emergence of a small population (13%) of cells with WT TLR8 DNA that was not detected in the transcript (supplemental Figure 9E). Macrophages derived from iPSC-p.P432L cells secreted more IL-6 and TNF-α compared with iPSC-derived cells with WT TLR8 following overnight stimulation with a low dose of TLR8 agonist (TL8-506, 25 ng/mL; Figure 5D). These cells also produced more IL-1β and IL-10 (data not shown). Stimulation of iPSC-derived macrophages with the TLR7 agonist CL264 demonstrated no differences in cytokine production (Figure 5D), suggesting that the TLR8 variants here do not alter responses to TLR7. Stimulation of macrophages through a nonendosomal TLR with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (TLR4 agonist) demonstrated similar levels of cytokines (Figure 5E).

Myeloid differentiated cells derived from patient iPSCs and gene-edited CD34s with the TLR8 variants demonstrated increased responsiveness to TLR8 stimulation. (A) Cytospin analysis of cells derived from neutrophil differentiation of WT or p.P432L iPSC clones from patient (P2) and WT or p.F494L iPSC clones from patient (P3) and their upregulation of phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in response to stimulation with the indicated doses of the TLR8-ligand TL8-506. (B) H&E stain of cytospin from cells derived from neutrophil differentiation of WT and gene-edited (p.P432L) healthy donor human CD34+ HPCs and their upregulation of phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in response to the TL8-506. Cells in flow plots are gated on CD45+CD66b+ neutrophils. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Cytospin analysis of cells derived from macrophage differentiation of WT or p.P432L induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) clones from patient (P2) and phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in response to stimulation with the indicated doses of the TLR8-ligand TL8-506. Cells are gated on CD45+CD14+ macrophages. (D-E) iPSC-derived macrophages with WT or p.P432L TLR8 from patient (P2) were cultured overnight with the indicated doses of TL8-506 (TLR8 agonist), CL264 (TLR7 agonist), or LPS (TLR4 agonist). (D) Cytokines were measured in the cell culture supernatant and demonstrate that macrophages with variant TLR8 produced significantly more IL-6 and TNF-α with low-dose TLR8 stimulation (TL8-506, 25ng/mL) compared with cells with WT TLR8. There was no difference in the cytokine response to TLR7 stimulation (CL264), and doses of CL264 <100 ng/mL did not result in cellular activation (data not shown). (E) WT and p.P432L macrophages had a similar response to the TLR4 ligand LPS with respect to production of TNF-α and IL-6. NS, no stimulation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and includes data from 3 independent experiments, analyzed by 2-way ANOVA. Findings that are statistically significant are denoted by an asterisk (*P ≤ .05).

Myeloid differentiated cells derived from patient iPSCs and gene-edited CD34s with the TLR8 variants demonstrated increased responsiveness to TLR8 stimulation. (A) Cytospin analysis of cells derived from neutrophil differentiation of WT or p.P432L iPSC clones from patient (P2) and WT or p.F494L iPSC clones from patient (P3) and their upregulation of phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in response to stimulation with the indicated doses of the TLR8-ligand TL8-506. (B) H&E stain of cytospin from cells derived from neutrophil differentiation of WT and gene-edited (p.P432L) healthy donor human CD34+ HPCs and their upregulation of phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in response to the TL8-506. Cells in flow plots are gated on CD45+CD66b+ neutrophils. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Cytospin analysis of cells derived from macrophage differentiation of WT or p.P432L induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) clones from patient (P2) and phosphorylated p65 (NF-κB) in response to stimulation with the indicated doses of the TLR8-ligand TL8-506. Cells are gated on CD45+CD14+ macrophages. (D-E) iPSC-derived macrophages with WT or p.P432L TLR8 from patient (P2) were cultured overnight with the indicated doses of TL8-506 (TLR8 agonist), CL264 (TLR7 agonist), or LPS (TLR4 agonist). (D) Cytokines were measured in the cell culture supernatant and demonstrate that macrophages with variant TLR8 produced significantly more IL-6 and TNF-α with low-dose TLR8 stimulation (TL8-506, 25ng/mL) compared with cells with WT TLR8. There was no difference in the cytokine response to TLR7 stimulation (CL264), and doses of CL264 <100 ng/mL did not result in cellular activation (data not shown). (E) WT and p.P432L macrophages had a similar response to the TLR4 ligand LPS with respect to production of TNF-α and IL-6. NS, no stimulation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and includes data from 3 independent experiments, analyzed by 2-way ANOVA. Findings that are statistically significant are denoted by an asterisk (*P ≤ .05).

Overall, these experiments demonstrate that both neutrophils and macrophages with the TLR8 variant have increased responsiveness to TLR8 stimulation, measured by phosphorylation of NF-κB and cytokine production. The identification of WT DNA in neutrophils and macrophages, but not CD34+ HPCs, derived from TLR8 variant iPSC clones suggests the possibility of a selective advantage for reversion mutations that may be silenced based on the lack of expressed cDNA.

Discussion

We report 6 unrelated male patients with an IEI characterized by neutropenia, infections, lymphoproliferation, B-cell defects, and in some cases bone marrow failure due to mutations in TLR8, the X-chromosome gene encoding TLR8, a pattern recognition receptor recognizing single-stranded RNA. Importantly, 5 of the 6 patients were mosaic for TLR8 variants, with 4 patients sharing the same mosaic variant. Mosaicism was <30%, suggesting an X-linked dominant phenotype. Detection of TLR8 variants in multiple tissues, including skin fibroblasts, suggests that mutational events causing disease likely occurred at a relatively early stage of embryogenesis and are not limited to the hematopoietic compartment in most patients. There are >430 recognized monogenic disorders associated with immunodeficiency.1 While genetic mosaicism in known disease-causing genes has been detected in patients with IEI through targeted sequencing,7 somatic mutation as a primary mechanism of monogenic IEI is rare.1 Our discovery suggests that mosaicism should be considered in disease discovery, which will require new approaches to exome and genome analysis to identify low-frequency genetic variation.

Single-gene defects in TLR8 have not been previously associated with monogenic human disease. Monogenic loss-of-function defects in signaling molecules downstream of TLR8 been associated with susceptibility to infection and a clinical phenotype distinct from our patients, including those in genes encoding IRAK-4, MyD88, IRF7, and the NF-κB protein complex.26-29 Loss-of-function variants in the gene encoding TLR3 lead to an IEI with susceptibility to herpes simplex encephalitis.30 Genetic variants in TLR7 were reported in patients with severe response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, although whether these confer altered responses to that or other viruses is unknown.31 Studies of the functional role of TLR8 in the immune response have been limited in large part due to difference in ligand binding between mouse and human TLR8. Deletion of Tlr8 in the mouse leads to increased TLR7 signaling due to the lack of inhibition by TLR8, with dendritic cells producing high amounts of cytokines causing spontaneous autoimmunity, autoantibodies, splenomegaly, and reduced B-cell numbers, similar to features in our patients.32 By contrast, transgenic expression of human TLR8 also caused increased cytokine production with hyperinflammation, even in mice with few as 20% of blood cells containing the human TLR8 transgene, demonstrating a strong biological effect of TLR8 signaling.33 Our data suggest that TLR7 signaling is not altered with patient TLR8 gain-of-function variants, based on similar cytokine responses with a TLR7 agonist in patient-derived macrophages.

The TLR8 variants here lead to a gain-of-function phenotype with patient-derived cells exhibiting hypersensitivity to ligand stimulation including increased NF-κB activation and cytokine production. The age of onset ranged from infancy to teenage years. While one of the patients with early-onset disease had a germline variant (P6), which could be predicted to lead to more severe disease than low-level genetic mosaicism, patients with mosaic disease presented between 1 and 16 years. Variant TLR8 was present in fibroblasts of 4 of 5 patients with mosaicism, suggesting that the mutation occurred at an early stage of development. While it was not possible to test DNA samples of patients with later-onset disease to determine whether mosaicism changed, analysis of peripheral blood samples from 2 patients at different time points in their disease demonstrated stable mosaicism (supplemental Figure 9F). The triggers for disease in patients with somatic TLR8 variants are uncertain, but variability of onset age in patients with the same genetic variant and similar levels of mosaicism suggest that environmental factors, most likely those known to stimulate TLR8, including pathogenic bacteria, viruses and commensal microbiota, may influence clinical severity and initiation of disease. Following onset of neutropenia, no patients had remission without therapy, suggesting that once triggered, the inflammatory process driving disease is not easily controlled and is potentially self-perpetuating. One patient (P5) had refractory ITP 11 years prior to onset of neutropenia. He had a period of disease remission following his ITP diagnosis; however, once he developed neutropenia, his disease progressed to require HCT. Interestingly, this fibroblasts from this patient did not carry the TLR8 variant, suggesting that the mutation may have been limited to the hematopoietic compartment in this case.

TLR8 is primarily expressed in neutrophils and other myeloid-derived cells. While the most unifying clinical phenotype of these patients is neutropenia, the other striking findings in patients were elevated serum cytokines and skewing of adaptive immune cell compartments. Patients had an activated T-cell phenotype and abnormal B-cell maturation, and most patients required immunoglobulin replacement therapy. While some of the patients here had an elevated type I transcriptional signature in their peripheral blood, this was much lower than patients with type I interferonopathies, and patients with TLR8 gain of function lack other clinical features of these disorders such as vasculopathy, interstitial lung disease, and central nervous system disease.34 Two patients developed oligoclonal T-cell populations within their bone marrow, with one patient diagnosed with T-LGL leukemia. A reduced frequency of transitional B cells, memory B-cell precursors, and class-switch memory B cells suggests a defect in both transitioning from the bone marrow and maturing into memory cells. High levels of serum BAFF, a B-cell survival and differentiation factor normally used by mature B cells, further correlated with the findings of low memory B cells.35 Together, the immunologic findings in these patients suggest cell-extrinsic effects of TLR8 gain of function, which we hypothesize is due to increased inflammatory cytokines, activated T cells, and possibly direct interactions with activated antigen-presenting cells bearing variant TLR8 in patients.

The phenotype of cytopenias and B-cell defects with lymphoproliferation in our patients has clinical overlap with other IEIs, including autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, deficiency of ADA2, and other primary immune regulatory disorders.36-39 There is also clinical and pathologic overlap between TLR8 gain of function and T-LGL leukemia, including elevated levels of IL-18 and IFN-γ, bone marrow findings of follicular hyperplasia, an activated T-cell phenotype, neutropenia, and progression to marrow failure in some patients.24,40-43 As many as 80% of T-LGL leukemia patients have neutropenia of uncertain etiology, with evidence for elevated Fas ligand from activated T cells mediating apoptosis of neutrophils and direct cytotoxic effects of activated T cells on immature neutrophils in that disease.24,40,42 Pathologic overlap in the marrow of patients with T-LGL leukemia has also been observed with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome.44

The consistent refractory neutropenia with lymphoproliferation makes TLR8 gain of function a unique entity among IEIs. While the mechanism of neutropenia in IEI is often attributed to autoimmunity, only a subset of patients here had detectable antineutrophil antibodies. Interestingly gain-of-function variants in another X-linked gene, WAS, are associated with X-linked severe congenital neutropenia due to a defect in myeloid differentiation.45-47 Differentiation of neutrophils from patient-derived iPSCs expressing TLR8 variants suggests there may be an intrinsic effect of gain-of-function TLR8 on the development and/or survival of neutrophils, based on the emergence of cells with WT TLR8 sequence. However, the dominant effect of a small number of cells clearly demonstrate a more complex phenotype. We hypothesize that the mechanism of neutropenia in patients with TLR8 gain of function is multifactorial, potentially including antineutrophil antibodies; proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-18, TNF-α, and IFN-γ impairing neutrophil differentiation; and direct and indirect effects of activated T cells and monocytes, including cytotoxicity and soluble Fas ligand.41,48

Our findings of 3 novel variants in TLR8 in 6 unrelated patients provides evidence for a new monogenic TLR8-associated IEI with neutropenia, infections, lymphoproliferation, B-cell defects, and in some patients bone marrow failure. We propose naming this disorder “inflammation, neutropenia, bone marrow failure, and lymphoproliferation caused by TLR8” (INFLTR8). Identification of mosaic variants causing disease demonstrates the importance of considering somatic mutation as a genetic cause of IEI, especially in molecularly uncharacterized disease. Considering the range of mosaicism detected in our cohort sufficient to cause disease (5% to 30%), it is likely that patients with a low percentage of mosaicism in a disease-causing gene may be overlooked by exome or genome sequencing. Treatment of the patients with TLR8 gain of function has proven challenging, and this is perhaps related to the multifactorial involvement of myeloid cells, T and B lymphocytes, and a proinflammatory environment. Further investigation of the functional consequences of TLR8 gain of function and identification of additional patients will lead to a better understanding of this new disorder and provide guidance for evidence-based therapy improving long-term outcome.

The authors will respond to e-mails to the corresponding authors for sharing methods and data. Patients presented here have not been previously reported.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to dedicate this article to Joseph and his family. The authors also wish to thank Joie Davis and Susan Price for their contributions toward clinical evaluation and care of patients.

Research support was provided by The Children’s Discovery Institute at Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, Center for Pediatric Immunology and St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation, The Jeffrey Modell Diagnostic and Research Center for Primary Immunodeficiencies at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, The Immune Deficiency Foundation, and the Washington University Rheumatic Diseases Research Resource-Based Center through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant P30AR073752 (M.A.C.). Support was provided by the Genome Engineering and iPSC Center at Washington University, the Bursky Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Programs (CHiiPs), and the Division of Intramural Research, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Support was provided for the Immunomonitoring Laboratory and immunoassay service by the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital, supported in part by a National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute cancer center support grant P30 CA091842. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. Support was provided by the Centralized Sequencing Initiative, Division of Intramural Research (DIR), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contracts HHSN261200800001E and 75N910D00024, task order 75N91019F00131.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.C. and J.A. designed the study, analyzed genomic, clinical, and experimental data, and wrote the manuscript; J.A., M.A.W., N.S., E.M.R., M.T.H., M.P.K., A.B., L.C.P., C.D.P., A.A.d.J., M.C., S.W.C., and S.S.D.R. performed experiments, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript; S.K., M.K., M. Shinawi, M.R., M. Similuk, E.K., M.J., Y.-S.L., J. J. Bednarski, C.B.-S., S.M.A., M.M.D., J.P., S.M.J., A.M.S., S.S.D.R., J. J. Bleesing, J.A.C., V.K.R., L.G.S., and M.A.C. provided clinical care to patients, interpreted genomic findings, performed clinical phenotyping and reviewed the manuscript; and R.G.-M., P.L.K., and M.C.D. analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Megan A. Cooper, 660 S. Euclid Ave, Box 8208, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: cooper_m@wustl.edu.

![Immunological findings in TLR8 gain-of-function patients. (A) Representative flow plots of T and B cells immunophenotyping showing a skewed ratio of CD4+ T cells expressing CD45RA or CD45RO (RA:RO ratio) and reduced class-switch memory B cells in a representative patient. (B) Quantitation of CD4:CD8 ratio, CD45RA:CD45RO ratio, percentage of effector memory T cells re-expressing CD45RA (CD45RA+ CCR7− effector memory T cells [TEMRAs]), and percentage of memory B cells and class-switch memory B cells relative to age-matched healthy male controls. In contrast to healthy controls, patients had a significantly reduced percentage of class-switch memory B cells. Young healthy male controls (<6 years) are indicated in red and young adult healthy male controls in green. Horizontal line indicates the median; a Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical evaluation. Findings that are statistically significant are denoted by an asterisk (*P ≤ .05).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/137/18/10.1182_blood.2020009620/3/m_bloodbld2020009620f3.png?Expires=1765991007&Signature=walOkRutlJ5Ihc3PkY0YP34z3ZMgoEP~73HBluAXBLUmdyO~24oWZVmOwBjKTs~zSl83FHOxJZ6xvuhHfRpoOHWAZFsRS65vuStOAOlXGF~~ByvwHSNQCG9JYpDWxxTkPtRf7lFRdqnUXP5QfnZoJDpd4w4aN17AYocKJQMLsmABGGLoG941VdJDUA96C2ktyp8zKpaOHP1vM9X4NPTcXQw6k95Z~fDuaWpUYXgnM8J7c1Ie33idIEEVvMxcIHABmMqtN2Po33FX~85dYCLWJUUZla6Y8pZfa1jb5v1dETdU5zwDmIVr5k5WV3OSNCb0lf5Ur0gc7TEvdBESSl7vdA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)