IgM-secreting plasma cell tumors are rare variants of typical isotype-switched multiple myeloma with a similar disease outcome. To probe the origin and clonal history of these tumors, we have analyzed VH gene sequences in 6 cases. Potentially functional tumor-derived VH genes were all derived from VH3, with the V3-7 gene segment being used by 4 of 6. All were somatically mutated, with a mean deviation from germline sequence of 5.2% (range, 3.1% to 7.1%). The distribution of replacement mutations was consistent with antigen selection in 4 of 6 cases, and no intraclonal heterogeneity was observed. Clonally related switched isotype transcripts were sought in 4 cases, and Cγ transcripts with tumor-derived CDR3 sequence were identified in 2 of 4. These findings indicate that IgM-secreting myelomas are arrested at a postfollicular stage at which somatic mutation has been silenced. Isotype switch variants show the cell of origin to be at the IgM to IgG switch point. These features indicate that the final neoplastic event has occurred at a stage immediately before that of typical isotype-switched myeloma. One possibility is that IgM myeloma involves the previously identified precursor cell of typical myeloma.

NORMAL B CELLS UNDERGO a series of recombinatorial and mutational changes during differentiation that lead to unique sequences in the variable region genes, VH and VL.1 These sequences provide clonal markers for tracking B-cell clones, and they also reflect the point reached in the differentiation process.2 V-gene sequences preserved in neoplastic cells therefore indicate features of the cell of origin and its clonal history.3 For certain B-cell tumors, such as those involved in cold agglutinin disease,4 there is evidence for bias in usage of VH genes that might reflect stimulation of the cell of origin by a B-cell superantigen.5 Analysis of somatic mutational patterns has also shown if the cell of origin has been exposed to the somatic mutational mechanism, which is generally activated in the germinal center.6 For example, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), evidence from VH genes has shown heterogeneity in the cell of origin, with 1 subset derived from a naive cell with unmutated sequences and another from cells that have undergone somatic mutation.7 Cases of follicular lymphoma and other tumors located in the germinal center also have somatically mutated V-genes.8-10 Interestingly, these tumors often display intraclonal heterogeneity resulting from ongoing mutational activity posttransformation.8 10

Normal somatically mutated IgM+ B cells reach a crossroad in the germinal center from which they can either escape into the blood as memory cells11 or undergo isotype switch and differentiation to plasma cells.12 The pathways followed are controlled by a regulatory network of largely T-cell–mediated influences, including CD40 ligand and cytokines.13,14 In neoplastic cells, transcripts of isotype switch variants have been observed in typical IgM+ CLL,15,16 and there is evidence for alternative transcripts in cases of follicular lymphoma and diffuse large-cell lymphoma.17 These findings suggest that tumor cells are capable of responding to differentiation signals in vivo.

Analysis of more than 100 VH genes in typical isotype-switched multiple myeloma (MM) has shown only minor bias in usage when compared with the normal expressed repertoire.18-20 A notable feature is that the V4-34 gene, which is known to be rearranged in 5% to 10% of normal B cells, has been found in only 1 case of MM, and that case had an unusual IgD paraprotein.21,22 Myeloma V-genes are invariably mutated and display clustering of replacement amino acids characteristic of antigen selection in approximately 24% of VH gene sequences.20 This reaches approximately 70% when analysis includes VLsequences.23 Lack of intraclonal heterogeneity is another common feature, and stability of tumor sequence is observed from presentation to plateau phase of disease.24 These features indicate that the final malignant event has occurred in a postfollicular cell. One intriguing question that has remained concerns the existence of a less differentiated precursor cell of the myeloma clone, because VDJ-Cμ transcripts have been identified with sequence identity to the tumor IgG or IgA clone.25-27 However, both the neoplastic potential of the cells producing these transcripts and their existence as separate cells remain in question. Difficulties in identifying the Cμ transcripts would also suggest that these cells are present at low frequency.27 28

In this study, we have analyzed VH genes of a rare subset of MM that secretes IgM. The question posed was whether these tumors arise from plasma cells generated before somatic mutation or whether they have accumulated mutations in a manner similar to the previously identified precursor cell of isotype-switched MM. Their maturation status was further assessed by analysis of variant transcript synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient material.

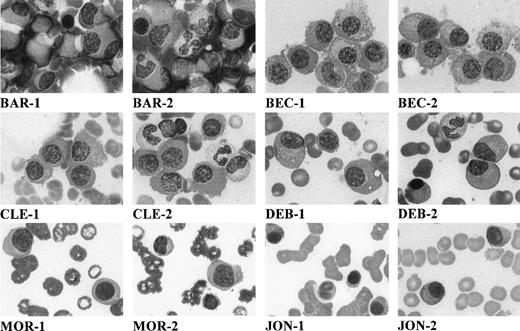

Bone marrow aspirates were obtained from 5 IgM MM and 1 IgM primary plasma-cell leukemia at the time of diagnosis. The presenting features of these patients are outlined in Table 1. The distinctive cytological features of these patients are shown in Fig 1. In Table 2, these features are contrasted with those of a cohort of 31 patients with IgM-secreting Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Morphology of myeloma cells on May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained bone marrow smears (original magnification × 1,000). Each patient is designated by initials, and 2 micrographs per patient are shown (numbered 1 and 2).

Morphology of myeloma cells on May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained bone marrow smears (original magnification × 1,000). Each patient is designated by initials, and 2 micrographs per patient are shown (numbered 1 and 2).

Cell preparation and phenotypic analysis.

Heparinized bone marrow aspirates were taken and used for May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained smears. Bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque and immunophenotyped as previously described.30

Genotypic analyses.

Cytogenetic analyses and probes and protocols used for fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and Southern blot analyses were as described.30a

Preparation of cDNA.

RNA was used as source material from tumor cells to amplify VH genes. This is a preferred approach to identify functional transcripts, because it reduces the likelihood of amplifying the aberrantly rearranged allele. Total RNA (5 to 10 μg) was isolated from the MNC fraction (4 to 10 × 106 cells) of the bone marrow aspirate using RNAzol B (Cinna Biotecx Labs, Inc, Houston, TX). Reverse transcription was performed using approximately 2 μg RNA and an outer Cμ1 constant region primer (Table 3) with a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For IgG transcripts, a Cγ1 primer was used to prime cDNA synthesis, and for IgA transcripts, a Cα1 primer was used (Table 3).

Amplification and sequencing of VH genes.

For analysis of the VH of tumor cells, one fifth to one third of a sample of cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a mixture of 5′-oligonucleotide VH leader primers specific for VH families 1 through 7 and a downstream nested Cμ2 primer (Table 3). For each sample, PCR conditions, cloning of amplified DNA, and sequence analysis were as previously reported.31 Analysis of V-gene sequences was by alignment to current EMBL/GenBank and V-BASE32 sequence directories using MacVector 4.0 software (International Biotechnologies Inc, New Haven, CT). At least 2 independent PCR amplifications were performed from each sample.

Investigation of tumor-related VH-Cγ/-Cα transcripts.

A 2-step nested PCR approach was used to investigate tumor-derived CH variant transcripts for patients CLE, DEZ, JON, and MOR. In step 1, one fifth of the cDNA was amplified using the appropriate 5′-VH leader primer together with Cγ1 or Cα1. In step 2, 1/20 of the PCR product of step 1 was directly amplified using a tumor-specific CDR2 (for CLE) or CDR3 (for DEZ, JON, and MOR) 5′-primer together with a nested downstream Cγ2 primer or a Cα2 primer (Table 3). Amplification conditions were modified to include an annealing temperature of 65°C for 1 minute in step 2. PCR products of predicted size were cloned and sequenced.

RESULTS

Tumor cell analyses.

The clinical and phenotypic data of the 6 IgM MM patients analyzed are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. It is noteworthy that 3 of 6 patients presented lytic bone lesions on bone radiography, with 1 of these patients also having hypercalcemia (Table 1). Cellular morphology assessed by stained bone marrow smears showed typical infiltrating plasma cells (Fig 1). Clearly, the 6 IgM MM patients had an excess of malignant plasma cells within the bone marrow, with a median value of 16% (range, 12% to 50%) versus 2% (range, 0% to 10%) in Waldenstrom’s disease (P < .01; Table 2). No expansion of lymphoid or lymphoplasmacytoid cells was observed, as compared with WM (Table 2). Immunophenotypic analysis showed the IgM MM tumor cells to be surface CD38++BB4+ and CD19−, confirming involvement of mature plasma cells and excluding any misdiagnosis with B-cell lymphoma (data not shown). Availability of material allowed cytogenetic analyses in 2 patients (BEC and MOR). In both patients, a t(11,14q32) translocation event was identified, which was further confirmed by FISH analysis in patient MOR. Southern blot analysis established the translocation breakpoint in patient MOR as occurring in the JH region and not in the switch region (data not shown).

VH gene use by tumor cells of patients.

The identification of tumor-derived VH genes was based on a common CDR3 signature sequence among multiple clones sequenced from each patient’s amplified cDNA.33Table 4 shows the number of tumor-derived clones identified of the total number of clones sequenced. Sequences not related to the tumor clone differed individually and were most likely derived from normal B cells. The VH gene used by each tumor, together with deviation in homology from their germline counterparts, are also shown in Table 4. The deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Fig 2. Nucleotide sequences have been deposited in the EMBL database (accession numbersAJ238036-AJ238040).

Deduced amino acid sequences of VH-Cμ transcripts from patients’ tumor cells. Comparisons are made with the closest germline VH genes. Uppercase letters, replacement mutations; lowercase letters, silent mutations. Replacement mutations in JH are underlined.

Deduced amino acid sequences of VH-Cμ transcripts from patients’ tumor cells. Comparisons are made with the closest germline VH genes. Uppercase letters, replacement mutations; lowercase letters, silent mutations. Replacement mutations in JH are underlined.

VH gene segments of 6 of 6 were derived from the VH3 family, and the individual germline genes used were V3-7 in 4 of 6 and V3-73 and V3-74 each in 1 case. The CDR3 length (6 to 10 amino acids) in these IgM tumors appears to be at the shorter end of reported length of CDR3s (2 to 25 amino acids) in functionally rearranged VH sequences from normal peripheral B cells.34 The CDR3 of patient CLE apparently lacked a D-segment gene and consisted of 7 amino acids that were part of JH6b, which is a long JH gene segment (Fig 2). Rare functional VH sequences from normal B cells in which CDR3 is derived from the JH gene segment have been previously reported.34 D segment genes of origin were not identified in any of the sequences using the recently established criteria of Corbett et al.35 Four of 6 cases used the common JH4b gene.34

Analysis of somatic mutations.

A significant degree of somatic mutation was evident in each tumor sequence (Table 4 and Fig 2). An average of 5.2% (range, 3.1% to 7.1%) deviation from germline was observed. Assessment of an influence of antigen selection on VH gene sequence has previously been based on a binomial distribution analysis of replacement and silent mutations.36 However, recent data from patterns in normal B cells have shown significant clustering of replacement mutations in CDRs even in nonfunctional sequences.37 Some of this reflects accumulation of mutations at hotspots.38 The main feature that distinguishes functional from nonfunctional sequences appears to be conservation of FR sequences.39 In the IgM myeloma sequences, hot spot mutations were observed in CDR1 (Ser 31) and in CDR2 (residue 50), as shown in Fig 2. Frequent mutations were also observed in FR3 at residues 79 and 93. Conservation of FR structural integrity was assessed using overall R:S ratios, and in 4 of 6 cases this ratio in FRs was less than 1.7 (Table 4), which is indicative of negative selection of R mutations.39

An assessment of intraclonal homogeneity among the tumor-derived clones, identified by shared CDR3 sequence, was made from at least 6 clones, except in the case of the previously published BAR VH sequence, in which only 3 clones were fully sequenced.29 A uniform feature of all the IgM tumors examined was a lack of intraclonal variation, as evident from identical VH gene sequences from tumor-derived clones.

Investigation of tumor-related isotype switch variants.

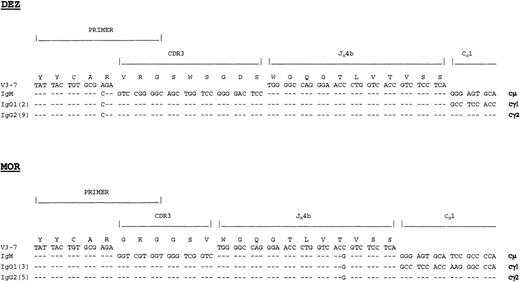

In 2 of 4 available cases, tumor-derived CDR3-Cγ transcripts were identified (DEZ and MOR), and in both cases, VDJ joined to Cγ1 and to Cγ2 were observed (Fig 3). Sequences from multiple clones of each variant transcript displayed intraclonal homogeneity and identity to CDR3-Cμ sequences. In all 4 cases, Cα transcripts linked to tumor VDJ were not found using a method previously shown to identify tumor-derived variant Cα transcripts in lymphoma cDNA.17

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the CDR3-Cγ transcripts from patients DEZ and MOR. The number of clones showing identical sequence are indicated in parentheses and comparison has been made with the tumor CDR3-Cμ transcript. The position of the 5′-CDR3 primer is indicated, and the position of the downstream Cγ primer (not shown) allowed identification of Cγ1 or Cγ2 transcripts.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the CDR3-Cγ transcripts from patients DEZ and MOR. The number of clones showing identical sequence are indicated in parentheses and comparison has been made with the tumor CDR3-Cμ transcript. The position of the 5′-CDR3 primer is indicated, and the position of the downstream Cγ primer (not shown) allowed identification of Cγ1 or Cγ2 transcripts.

DISCUSSION

In this investigation of IgM-secreting myeloma, VH gene analysis has been used to probe the maturation status and stage of arrest of the neoplastic cell of origin. A high level of somatic mutation was a consistent feature of these IgM-secreting tumors, indicating that the cell of origin has traversed the germinal center and activated the somatic hypermutation mechanism. Although the number of cases in this study is small, the level of mutation appears lower (average 5.2% deviation from germline; range, 3.1% to 7.1%) than in 114 cases of typical Ig class-switched myeloma (8.9%; range, 2.5% to 22.4%).19-23 The level in the IgM-secreting tumors appeared closer to mutational frequencies in preswitched IgM memory cells11 and in IgM tonsillar cells.40 The pattern of somatic mutations in tumor VH genes was indicative of replacement events in CDR1 and CDR2; however, intrinsic mutational hot spots may mask analysis of antigen-specific positive selection.37-39 Nevertheless, significantly low overall R:S ratios in FRs in the majority of cases suggested selective pressure to conserve functional structure by minimizing R events.39However, the role of CDR3, which lies at the center of the antigen-binding site,41 is difficult to assess in this type of analysis, and VL is additionally important in antigen recognition.42 Taking these findings together, it appears that the final transformation event has occurred in a cell with characteristics of an IgM+ memory cell.11The absence of intraclonal heterogeneity suggests that the stage of final transformation is postfollicular, which is, again, a feature common to isotype-switched myeloma.18-20 22-24

Insight into the stage of arrest is provided from the analysis of alternative isotype transcripts. In 2 of 4 IgM+ myeloma cases, it was possible to identify CDR3-Cγ1 and CDR3-Cγ2 transcripts in each. These transcripts also displayed sequence identity to tumor VDJ and intraclonal homogeneity. Although these tumors are secreting high levels of IgM, cells within the clone appear to be undergoing isotype switching to Cγ. In contrast, although typical myeloma cells are isotype-switched, there is evidence of bone marrow-derived tumor cells producing VDJ-Cμ transcripts with complete identity to tumor VDJ, as assessed from CDR2 or CDR3, and lack of any intraclonal sequence variation.25-27 The nature of the IgM+ precursor cell in conventional myeloma has not yet been fully characterized, partly due to the very low numbers present, but one possibilty is that IgM-secreting myeloma cells involve this precursor cell. The stage of transformation in IgM myeloma may immediately precede that in typical myeloma. It is also at this point that the cell of origin in IgM+ WM is thought to arise,43,44 but morphological and immunophenotypic features suggest that this cell may be less mature.45 In addition, no isotype-switch variants were found in our analysis of 6 WM tumors (Sahota SS, et al, manuscript in preparation).

The question arises as to whether the alternate isotypes originate from the same cell or are the products of separate, clonally related progeny. Evidence for separate populations was provided from our recent study of cases of lymphoplasmacytoid lymphomas synthesizing clonally related IgM and IgG.46 Divergent patterns of somatic mutation in the 2 isotype transcripts in 2 of 5 cases proved that there were 2 clonally related cell populations, 1 of which had switched presumably by deletional recombination. This might suggest that, in IgM-secreting myeloma, a few cells have undergone deletional switching to IgG1 or IgG2. In contrast, in typical isotype-switched myeloma, the majority have undergone isotype switch to a single constant region, but there appear to be a few nonswitched cells and a few that have switched to other constant regions.25-27 The fact that isotype switching tends to occur on both alleles, both in mice47and in IgG follicle center lymphoma, as shown by FISH analysis,48 makes it unlikely that alternate isotypes originate from the same cell bytrans-splicing.49

In 2 of the IgM MM patients, 1 allele is also involved in chromosomal translocations, which in patient MOR was shown to map in the JH region. Tumor-derived CDR3-Cγ1 and -Cγ2 transcripts were also identified in patient MOR; in this patient, alternate isotypes arising from the second allele bytrans-splicing are unlikely. However, contribution by downstream CH regions on the functional allele could occur, possibly by RNA processing. It is noteworthy that, in IgM follicular lymphoma, such downstream elements also rearrange by deletional recombination.48 Similar t(11;14q32) translocations have been detected in 10% to 15% of typical isotype-switched MM (Avet-Loiseau H, et al, manuscript submitted; reviewed in Hallek et al50). Translocations involving chromosome 14q32 may furthermore be key events in the pathogenesis of MM.50 However, it is evident that not all of these events occur during the process of isotype switch, and it would appear that switch recombination is not a prerequisite for development of MM.

Location of the IgM-secreting tumors in the bone marrow supports the concept that somatically mutated IgM+ B cells can leave the germinal center, circulate in the blood,11 and move to the marrow.51 The lack of ongoing mutations in these tumors and the apparent sequence identity between IgM and IgG variants based on CDR3-CH sequence would be consistent with isotype switch occurring in a site where somatic mutation is silent, possibly in the marrow. This clearly precludes the unmutated IgM-secreting plasma cell of the primary response as the cell of origin of these tumors.12 Hypermutated IgM+ mature normal B cells, isolated from the marrow, have been shown to secrete IgM when cultured together with autologous bone marrow T cells and T-cell–derived cytokines.51 These IgM+ cells, which increase with age,52 could represent potential normal precursors of IgM-secreting plasma cells. In normal bone marrow, there are few identifiable IgM-secreting plasma cells, but IgM antibody against tetanus toxin can be induced in bone marrow cells after vaccination.53 Extensively mutated IgM+ plasma cells have been found in normal gut mucosa, with the level of somatic mutation comparable to IgA plasma cells at this site.54

Morphologically and phenotypically, these myelomas appear more mature than the cells of WM, and they have evidently acquired the features that lead to a clinical course of disease similar to typical MM. The relationship of these tumors to the isotype-switched cells of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is unclear. It is rather surprising that the less mature IgM-positive cells lead to clinical features indistinguishable from conventional myeloma, whereas isotype-switched cells of MGUS do not. One possibility is that, although MGUS may convert to MM in some cases,55 the route to MGUS is distinct from that to MM. This suggestion is supported by the finding of intraclonal variation, which is indicative of a residual influence of the germinal center, in a subset of MGUS.31Clearly, we need to probe further into the differences between these tumors that have such impact on clinical outcome.

Supported by The Leukaemia Research Fund, UK.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Surinder S. Sahota, PhD, Molecular Immunology Group, Tenovus Laboratory, Southampton University Hospitals, Tremona Road, Southampton SO16 6YD, UK; e-mail: sss1@soton.ac.uk.