Abstract

Previous studies have established a role of vascular-disrupting agents as anti- cancer agents. Plinabulin is a novel vascular-disrupting agent that exhibits potent interruption of tumor blood flow because of the disruption of tumor vascular endothelial cells, resulting in tumor necrosis. In addition, plinabulin exerts a direct action on tumor cells, resulting in apoptosis. In the present study, we examined the anti–multiple myeloma (MM) activity of plinabulin. We show that low concentrations of plinabulin exhibit a potent antiangiogenic action on vascular endothelial cells. Importantly, plinabulin also induces apoptotic cell death in MM cell lines and tumor cells from patients with MM, associated with mitotic growth arrest. Plinabulin-induced apoptosis is mediated through activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage. Moreover, plinabulin triggered phosphorylation of stress response protein JNK, as a primary target, whereas blockade of JNK with a biochemical inhibitor or small interfering RNA strategy abrogated plinabulin-induced mitotic block or MM cell death. Finally, in vivo studies show that plinabulin was well tolerated and significantly inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in a human MM.1S plasmacytoma murine xenograft model. Our study therefore provides the rationale for clinical evaluation of plinabulin to improve patient outcome in MM.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is still an incurable malignancy because of the development of drug-resistant phenotype after prolonged therapy.1,2 Several studies that used various cancer models, including MM, have provided evidence of therapeutic potential for vascular-disrupting agents (VDAs).3-5 VDAs disrupt functional tumor vasculature, reducing tumor blood flow, and thereby causing tumor collapse with subsequent anoxia and tumor regression.6 The importance of the vascular network as a therapeutic target to inhibit tumor growth7-10 has led to the development of novel VDAs that act in a ligand-directed manner and prevent tubulin polymerization (eg, plinabulin, fosbretabulin, ABT-751), which clearly differentiates them from the microtubule-stabilizing agents (eg, taxanes and epothilones).8,11-13

Several tubulin-stabilizing agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of different cancers, including breast, testicular, and ovarian cancers, as well as Kaposi sarcoma. However, in MM there has been little clinical success with docetaxel and paclitaxel.3-5 All of these agents showed modest anti-MM activity, associated with severe toxicity.12,14-17 Mechanistic studies show that all of these VDAs target tubulin but at different site and therefore are also known as tubulin poison or mitotic spindle poison. Many tubulin poisons are under investigation for their antitumor activity, but only a few of them are successful in the clinic. One possibility for their failure could be because of poor therapeutic index or imbalance between efficacy and toxicity18-20

A recent preclinical study showed that small molecule tubulin polymerization inhibitor CYT997 induces MM cell death in vitro; however, its clinical activity remains to be evaluated. Recent medicinal chemistry efforts led to the discovery and development of a novel VDA plinabulin (NPI-2358). Plinabulin is a synthetic analog of the diketopiperazine phenylahistin (halimide) discovered from marine and terrestrial Aspergillus sp. Plinabulin is structurally different from colchicine and its combretastatin-like analogs (eg, fosbretabulin) and binds at or near the colchicine binding site on tubulin monomers. Previous studies showed that plinabulin induced vascular endothelial cell tubulin depolymerization and monolayer permeability at low concentrations compared with colchicine and that it induced apoptosis in Jurkat leukemia cells. In addition, a phase 1 study of plinabulin as a single agent in patients with advanced malignancies (lung, prostrate, and colon cancers) showed a favorable pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamics, and safety profile; phase 2 study combining plinabulin with docetaxel in patients with non–small cell lung cancer showed encouraging safety, pharmacokinetic, and efficacy data.21,22

In the present study, we show that the novel VDA plinabulin induces cell death in MM cells, without affecting viability of normal PBMCs. The antiproliferative activity of plinabulin is because of its ability to trigger early mitotic arrest in MM cells. Blockade of JNK abrogated plinabulin-induced mitotic arrest or MM cell death. Moreover, we show that plinabulin inhibits tumor growth in human plasmacytoma mouse xenograft models at well-tolerated doses. These preclinical studies provide the rationale for the development of plinabulin as a novel therapy to improve patient outcome in MM.

Methods

Cell culture

Human MM cell lines MM.1S, MM.1R, RPMI-8226, and INA-6 were cultured in complete medium (RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2mM l-glutamine). MM patient tumor cells were purified by CD138+ selection with the use of Auto MACS (Miltenyi Biotec). Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Helsinki protocol. PBMCs from healthy donors were maintained in culture medium, as mentioned above. Plinabulin was obtained from Nereus Pharmaceuticals Inc. Stock solutions were made in 100% DMSO and stored in amber vials at −80°C.

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell viability was assessed by MTT (Chemicon International Inc), as previously described.23 Percentage of cell death in control versus treated cells was determined by Trypan Blue Exclusion assay. Apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining assay kit, as per manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems Inc) and analyzed on a FACSCaliber (Becton Dickinson). To examine the effects of plinabulin on mitosis, MM cells were stained with antibody against phospho-histone H3 (Cell Signaling) and analyzed by flow cytometry.24

Thymidine incorporation assay for coculture experiments

MM cells were incubated in the presence or absence of BM stroma cells, pulsed with 3[H]-thymidine (0.5 μCi [0.018 Bq]), harvested, and counted with the use of a LKB betaplate scintillation counter (Wallac).25

Western blot analysis

Protein lysate from control and drug-treated cells were subjected to immunoblotting against PARP, caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, pJNK, or GAPDH antibodies. (Cell Signaling,) Blots were then developed by ECL (Amersham).

Small interfering RNA transfection

The JNK small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown was performed with signal silence SAPK/JNK siRNA kit (Cell Signaling). Transfection was performed with cell line Nucleofactor Kit V solution (Amaxa Biosystems/Lonza), as per the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, MM.1S cells were transfected with JNK-I or JNK-II siRNA (Cell Signaling) and then separated into 2 groups. The first group of cells was cultured for 72 hours; protein lysates were then analyzed for the expression of JNK-I or JNK-II by immunoblotting with the use of anti-JNK Ab. In the second group MM.1S cells were transfected with JNK siRNA; after 24 hours of incubation, plinabulin (8nM) was added for an additional 48 hours, followed by analysis of viability with the MTT assay.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells were grown in 4-well chambers slides (BD Falcon) and treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 24 hours. Cells were then washed twice in PBS, fixed in 0.4% of paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature, permeabilized in 0.05% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes, and blocked in blocking buffer (3% BSA plus 0.05% Triton X-100). Fixed cells were incubated with primary Ab (α-tubulin [1:2000]/pericentrin [1:1000]) and secondary antibody (anti–mouse Alexa 488 [1:2000]/anti–rabbit Alexa 568 [1:1000]) (Invitrogen) for 1 hour each, then washed with PBS, and mounted with prolong gold antifade mounting medium (Invitrogen). Hoechst was used to stain the nuclei.

Human plasmacytoma xenograft

The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal studies. The in vivo anti-MM activity of plinabulin was assessed with the xenograft tumor model, as previously described.26-28 Briefly, CB-17 male SCID mice (n = 12; Charles River Laboratories) were subcutaneously injected with MM.1S cells (5.0 × 106) in 100 μL of serum-free RPMI-1640 medium. When tumors were measurable (∼ 350-400 mm3) ∼ 2 weeks after cell injection, mice were treated intraperitoneally with plinabulin (7.5 mg/kg) or vehicle alone for 21 days on a twice-weekly schedule (day 1/day 4). The dosing vehicle for plinabulin consisted of 12% polyethylene glycol 400 (Fluka; Sigma), 8% solutol, and 80% double distilled water and stored in amber vials.

In situ detection of apoptosis and assessment of microvessel density

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of differences observed in drug-treated versus control cultures was determined with the Student t test. Tumor volume differences were determined with a Student t test. The minimal level of significance was P < .05. Survival of mice was measured with Kaplan-Meier curves (GraphPad Software Inc).

Results

Anti-MM activity of plinabulin

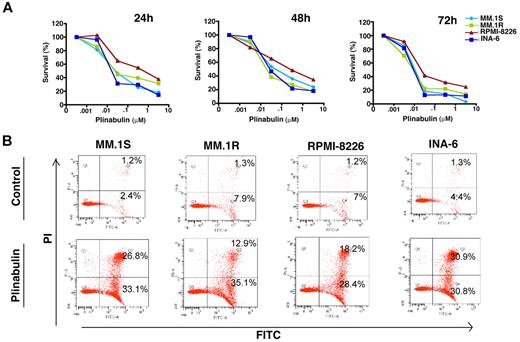

Human MM cell lines MM.1S, MM.1R (Dex-resistant), RPMI-8226, and INA-6 (IL-6–dependent) were treated with plinabulin at different concentrations (range, 1nM to 10μM) for 24, 48, and 72 hours, and cell viability was measured by MTT assays. As shown in Figure 1A, plinabulin significantly decreased the viability of all the MM cell lines in a time- and dose-dependent manner (IC50 ranges from 8nM to 10nM for different cell lines). Importantly, plinabulin-induced decrease in cell viability was because of apoptosis, as evidenced by a significant increase in the number of Annexin V+/PI− cells (Figure 1B).

Plinabulin inhibits growth and triggers apoptosis in MM. (A) Human MM cell lines MM.1S, MM.1R, RPMI-8226, and INA-6 were treated with plinabulin (dose range, 0.001-10μM) for 24, 48, and 72 hours; cell viability was measured with MTT assays. Data presented are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (P < .05 for all the cell lines at different time points). (B) MM.1S, MM.1R, RPMI-8226, and INA-6 cell lines were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours, and apoptosis was measured with Annexin V/PI binding assay by flow cytometry (P < .05; n = 3). A representative graph from 3 independent experiments is shown. Right quadrant: top panel, Annexin V+/PI+ cells; bottom panel, Annexin V+.

Plinabulin inhibits growth and triggers apoptosis in MM. (A) Human MM cell lines MM.1S, MM.1R, RPMI-8226, and INA-6 were treated with plinabulin (dose range, 0.001-10μM) for 24, 48, and 72 hours; cell viability was measured with MTT assays. Data presented are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (P < .05 for all the cell lines at different time points). (B) MM.1S, MM.1R, RPMI-8226, and INA-6 cell lines were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours, and apoptosis was measured with Annexin V/PI binding assay by flow cytometry (P < .05; n = 3). A representative graph from 3 independent experiments is shown. Right quadrant: top panel, Annexin V+/PI+ cells; bottom panel, Annexin V+.

Plinabulin triggers mitotic arrest in MM cells

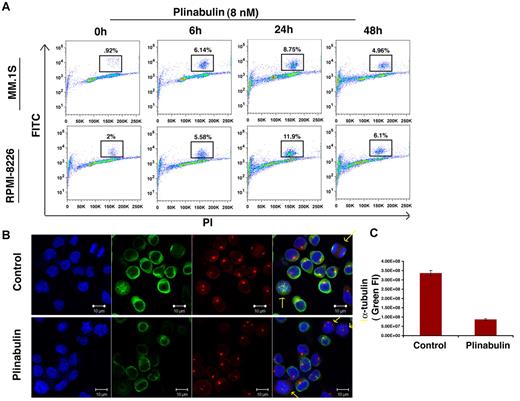

VDAs are known to block the polymerization of tubulin monomers into newly formed microtubules and microfilaments, thereby causing mitotic arrest.24 Phosphorylation of histone H3 is a marker for mitotic progression, and our data show that plinabulin triggers > 4-fold increase in the number of phosphor-histone H3-positive cells as early as 6 hours after treatment. However, after 48 hours of plinabulin treatment the number of histone-positive cells declined with a concomitant increase in the percentage of dead cells (Figure 2A). These data indicate that plinabulin induces mitotic failure early, whereas longer exposure leads to cell death. In agreement with our phospho-histone H3 data, plinabulin blocked cells in metaphase with irregular chromosome alignment (Figure 2B). Confocal images show fluorescence intensity of α-tubulin (green) to be significantly down-regulated in plinabulin-treated cells compared with vehicle-treated control cells (Figure 2C). These data suggest that plinabulin disrupts the formation of microtubules and microfilaments, causing mitotic arrest in proliferating MM cells.

Plinabulin treatment leads to mitotic block in MM. (A) MM cell lines MM.1S and RPMI-8226 were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 6, 24, and 48 hours, followed by analysis for histone H3 phosphorylation with the use of flow cytometry. Data are representation of 3 independent experiments. (B) MM.1S cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 24 hours and stained for α-tubulin, pericentrin, and Hoechst. (C) Fluorescence intensity (FI) of α-tubulin (green fluorescence) was measured with the use of Velocity software (Improvision). Representative figures (C-D) are from 4 independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD.

Plinabulin treatment leads to mitotic block in MM. (A) MM cell lines MM.1S and RPMI-8226 were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 6, 24, and 48 hours, followed by analysis for histone H3 phosphorylation with the use of flow cytometry. Data are representation of 3 independent experiments. (B) MM.1S cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 24 hours and stained for α-tubulin, pericentrin, and Hoechst. (C) Fluorescence intensity (FI) of α-tubulin (green fluorescence) was measured with the use of Velocity software (Improvision). Representative figures (C-D) are from 4 independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD.

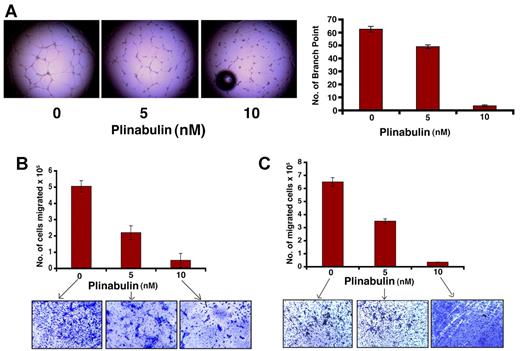

Plinabulin inhibits tubule formation and migration of endothelial as well as MM cells

To examine the antivascular activity of plinabulin, we performed capillary tubule formation assays with the use of HUVECs. Even low concentrations of plinabulin (5nM treatment for 12 hours) triggered significantly decreased tubule formation in HUVECs (Figure 3A; 70%-80% decrease; P < .05; n = 3). To further confirm the antivascular activity of plinabulin, we examined the effects of plinabulin on the chemotactic motility of both MM and endothelial cells with the use of trans-well insert assays. A marked reduction was observed in serum-dependent migration in plinabulin-treated MM cells (Figure 3B; 58% ± 2.1% inhibition in plinabulin-treated vs control; P < .05). At this concentration 5nM plinabulin for 12 hours did not affect survival of MM cells (> 95% viable cells). Similar effects of plinabulin were noted against HUVECs (Figure 3C; 48% ± 1.7% decrease in migration; P < .05). Together, these data suggest that plinabulin disrupts tumor vasculature by inhibiting both cell migration and endothelial cell tubule formation.

Antivascular activity of plinabulin. (A) HUVECs were treated with plinabulin (5nM) for 12 hours and assessed for in vitro vascularization with the use of matrigel capillary-like tube structure formation assays (magnification, 4×/0.10 NA oil; media, EBM-2). (Left) Micrograph images show the effect of plinabulin on capillary tube branch formation. (Right) The bar graph represents quantification of capillary-like tube structure formation in response to plinabulin. Branch points in several random view fields/well were counted; values were averaged; and statistically significant differences were measured with the Student t test. (B-C) For migration assay, HUVECs and MM cells were treated with plinabulin (5nM and 10nM) for 12 hours; cells were > 90% viable at this time point. Cells were washed and cultured in serum-free medium, plated on a fibronectin-coated polycarbonate membrane in the upper chamber of trans-well inserts, and exposed for 2 hours to serum containing medium in the lower chamber. Cells migrating to the bottom face of the membrane were fixed with 90% ethanol and stained with crystal violet (magnification, 10×/0.25 NA oil). A total of 3 randomly selected fields were examined for cells that had migrated from the top to the bottom chambers. (B-C top) Bar graph represents quantification of migrated cells. Data presented are means ± SD (n = 2; P < .05 for control versus plinabulin). (B-C bottom) Image is representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

Antivascular activity of plinabulin. (A) HUVECs were treated with plinabulin (5nM) for 12 hours and assessed for in vitro vascularization with the use of matrigel capillary-like tube structure formation assays (magnification, 4×/0.10 NA oil; media, EBM-2). (Left) Micrograph images show the effect of plinabulin on capillary tube branch formation. (Right) The bar graph represents quantification of capillary-like tube structure formation in response to plinabulin. Branch points in several random view fields/well were counted; values were averaged; and statistically significant differences were measured with the Student t test. (B-C) For migration assay, HUVECs and MM cells were treated with plinabulin (5nM and 10nM) for 12 hours; cells were > 90% viable at this time point. Cells were washed and cultured in serum-free medium, plated on a fibronectin-coated polycarbonate membrane in the upper chamber of trans-well inserts, and exposed for 2 hours to serum containing medium in the lower chamber. Cells migrating to the bottom face of the membrane were fixed with 90% ethanol and stained with crystal violet (magnification, 10×/0.25 NA oil). A total of 3 randomly selected fields were examined for cells that had migrated from the top to the bottom chambers. (B-C top) Bar graph represents quantification of migrated cells. Data presented are means ± SD (n = 2; P < .05 for control versus plinabulin). (B-C bottom) Image is representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

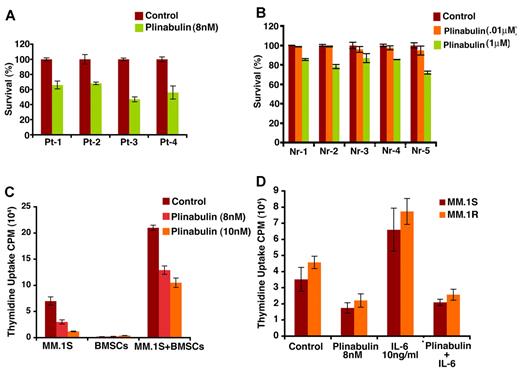

Plinabulin induces cell death in patient MM (CD138+) cells without effecting viability of normal mononuclear cells

Patient MM cells (CD138+) were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours), and cell viability was measured with Trypan Blue Exclusion assays. Two patients were newly diagnosed, and 2 other patients were undergoing therapy. As noted in MM cell lines, plinabulin induced significant cell death in patient MM cells (Figure 4A; n = 3; P < .05). Importantly, a minimal decrease in viability of normal PBMCs was observed (Figure 4B). These results indicate potent anti-MM activity of plinabulin and suggest a favorable therapeutic index.

Plinabulin induces cell death in patient tumor (CD138+) cells and inhibits BMSC-induced MM cell growth. (A) Purified patient MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours, and cell death was measured with Trypan Blue Exclusion assays. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05 for all patients). (B) PBMCs from 5 healthy donors were treated with plinabulin (0.1μM and 1μM) for 48 hours and then analyzed for viability with MTT assay. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05; n = 3). (C) MM.1S cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours) in the presence or absence of 3 different patient BMSCs, and cell growth was measured with thymidine incorporation. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05; n = 3,). (D) MM.1S and MM.1R cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours) in the presence or absence of rhIL-6 (10 ng/mL), and then cell growth was measured with thymidine incorporation. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05 for all the cell lines).

Plinabulin induces cell death in patient tumor (CD138+) cells and inhibits BMSC-induced MM cell growth. (A) Purified patient MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours, and cell death was measured with Trypan Blue Exclusion assays. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05 for all patients). (B) PBMCs from 5 healthy donors were treated with plinabulin (0.1μM and 1μM) for 48 hours and then analyzed for viability with MTT assay. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05; n = 3). (C) MM.1S cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours) in the presence or absence of 3 different patient BMSCs, and cell growth was measured with thymidine incorporation. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05; n = 3,). (D) MM.1S and MM.1R cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours) in the presence or absence of rhIL-6 (10 ng/mL), and then cell growth was measured with thymidine incorporation. Data presented are mean ± SD of triplicate samples (P < .05 for all the cell lines).

Plinabulin blocks BM stromal cell–induced MM cell growth

MM.1S and MM.1R MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours), in the presence or absence of BM stem cells (BMSCs); cell proliferation was then analyzed by thymidine incorporation assay. As shown in Figure 4C, plinabulin significantly inhibits BMSC-induced MM cell growth (P < .05; n = 3). Our prior studies showed that adhesion of MM cells to BMSCs triggers transcription and secretion of MM cell growth and survival factors such as IL-6.30 We therefore next examined whether plinabulin retains its anti-MM activity even in the presence of IL-6. MM.1S and MM.1R cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours) in the presence or absence of IL-6 (10 ng/mL); cell proliferation was then analyzed by thymidine incorporation assay. Results (Figure 4D) show that plinabulin decreases MM cell proliferation even in the presence of IL-6.

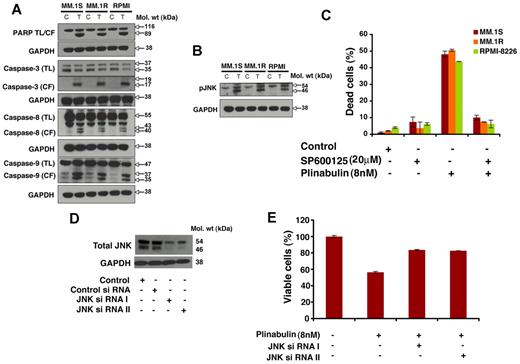

Plinabulin-induced apoptosis is associated with activation of caspases

MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours), and protein lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Plinabulin triggers PARP cleavage in all 3 MM cells (Figure 5A). Furthermore, plinabulin induces activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 (Figure 5A). These findings indicate involvement of both intrinsic (caspase-8–mediated) and extrinsic (caspase-9–mediated) apoptotic signaling during plinabulin-induced MM cell death.

Plinabulin-induced apoptosis in MM cells is associated with activation of caspases and JNK. (A) MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours and harvested, and total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with the use of antibodies against PARP, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, or GAPDH. TL indicates total length; CF, cleaved fragment. Blots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) MM.1S and MM.1R MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours and harvested, and total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against pJNK or GAPDH. Blots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 MM cells were pretreated with the biochemical inhibitor of JNK (SP600125; 20μM for 30 minutes), followed by plinabulin treatment (8nM, 48 hours). After incubation, cell death was measured with the Trypan Blue assay (n = 3; P < .05). (D) MM.1S cells were transfected with 100nM siRNA JNK I or JNK II or scrambled siRNA with the use of the cell line Nucleofactor Kit V solution (Amaxa Biosystems/Lonza) for 72 hours, and protein expression of JNK-I or JNK-II was examined by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for JNK I and II. (E) Transfected MM.1S cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours), and cell viability was measured with the MTT assay (n = 3; P > .05).

Plinabulin-induced apoptosis in MM cells is associated with activation of caspases and JNK. (A) MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours and harvested, and total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with the use of antibodies against PARP, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, or GAPDH. TL indicates total length; CF, cleaved fragment. Blots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) MM.1S and MM.1R MM cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM) for 48 hours and harvested, and total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against pJNK or GAPDH. Blots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 MM cells were pretreated with the biochemical inhibitor of JNK (SP600125; 20μM for 30 minutes), followed by plinabulin treatment (8nM, 48 hours). After incubation, cell death was measured with the Trypan Blue assay (n = 3; P < .05). (D) MM.1S cells were transfected with 100nM siRNA JNK I or JNK II or scrambled siRNA with the use of the cell line Nucleofactor Kit V solution (Amaxa Biosystems/Lonza) for 72 hours, and protein expression of JNK-I or JNK-II was examined by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for JNK I and II. (E) Transfected MM.1S cells were treated with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours), and cell viability was measured with the MTT assay (n = 3; P > .05).

Plinabulin-induced apoptosis in MM cells requires JNK

Cell death or apoptosis induced by plinabulin can also be regulated through a stress-inducible regulatory network that includes activation of JNK. We therefore next examined effects of plinabulin on phosphorylation of JNK. Treatment of MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 cells with plinabulin (8nM, 48 hours) triggered phosphorylation of JNK (Figure 5B).

To further confirm the role of JNK in plinabulin-induced cell death, we pretreated MM.1S, MM.1R, and RPMI-8226 MM cells with a biochemical inhibitor of JNK (SP600125, 20μM for 30 minutes), followed by plinabulin treatment (8 nm, 48 hours), and analysis of cell death with the use of the Trypan Blue cell viability assay. Plinabulin-induced cell death was significantly blocked (80%-85%) in the presence of JNK inhibitor (Figure 5C). We further confirmed the involvement of JNK with the use of the siRNA strategy. Blockade of JNK-I or JNK-II with siRNA significantly abrogated plinabulin decrease in cell viability (Figure 5E). Together these data confirm an obligatory role of JNK during plinabulin-induced MM cell death.

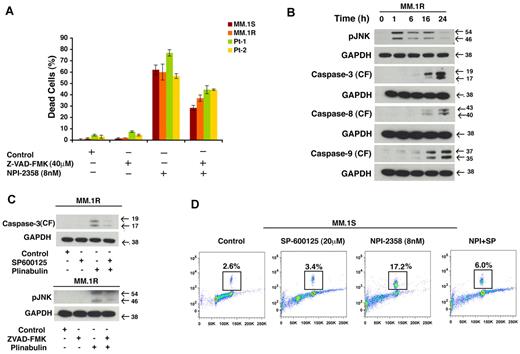

Plinabulin-induced cell death is dependent on JNK and caspase activation

To further investigate the role of caspases in plinabulin-induced cell death, we pretreated MM.1S, MM.1R, and primary patients cells with Pan caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK; 40μM, 2 hours) followed by plinabulin (8nM) treatment for another 48 hours. After the desired time point Trypan Blue assay was performed. Our result (Figure 6A) shows that in the presence of PAN caspase inhibitor, plinabulin-induced cell death was significantly rescued. To further investigate whether JNK is the primary target for plinabulin, we examined the effect of plinabulin on activation of JNK by measuring the phosphorylation of JNK as a function of time. To do so we treated MM cells with a higher concentration of plinabulin (20nM) for different time points, then we checked JNK and caspase activation by Western blot analysis. Our result (Figure 6B) shows that JNK activation occurs as early as 1 hour after plinabulin treatment, whereas caspases were activated only at later time point such as 16 and 24 hours. All of these results together suggest JNK as a primary target for this drug. To investigate further about JNK or caspase dependence, we treated MM cells with JNK inhibitor and checked for caspase-3 cleavage, and we treated cells with caspase inhibitor and checked for JNK activation. In both situations caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 6C top) and JNK (Figure 6C bottom) activation was blocked suggesting that JNK and caspases are working in an autoamplification loop and their activity depends on each other. Our earlier result showed plinabulin induced mitotic block at an early time point; therefore, we determined whether JNK is also playing a role in antimitotic activity of plinabulin. To do so, we pretreated MM.1S cells with SP600125, and then plinabulin was added for another 16 hours. Results (Figure 6D) showed that plinabulin-induced mitotic arrest was significantly abrogated.

Cell death induced by plinabulin depends on JNK as well as caspases. (A) MM.1S, MM.1R, and primary patients cells were pretreated with PAN caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (40μM, 2 hours) followed by plinabulin treatment (8nM, 48 hours). After the desired time point cell death were measured with the Trypan Blue assay (n = 2; P > .05). (B) MM.1R cells were treated with higher doses of plinabulin (20nM) for 1, 6, 16, and 24 hours, and Western blot analyses were performed with antibodies against pJNK, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, or GAPDH. CF indicates cleaved fragment. Results were representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (C top) MM.1R cells were treated with PAN caspase inhibitor for 2 hours, and then plinabulin (8nM) was added for an additional 48 hours. Protein lysate was prepared; phosphorylation of JNK was checked with Western blot analysis. (C bottom) MM.1R cells were pretreated with JNK inhibitor SP600125 (20μM, 2 hours), and plinabulin (8nM) was added for another 48 hours. After 48 hours protein lysate was prepared and cleaved caspase-3 expression was checked with Western blot analysis. (D) MM cell line MM.1S was pretreated with SP600125 (20μM) for 2 hours, and plinabulin (8nM) was added for an additional 16 hours followed by analysis for histone H3 phosphorylation with the use of flow cytometry. Data are representation of 3 independent experiments.

Cell death induced by plinabulin depends on JNK as well as caspases. (A) MM.1S, MM.1R, and primary patients cells were pretreated with PAN caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (40μM, 2 hours) followed by plinabulin treatment (8nM, 48 hours). After the desired time point cell death were measured with the Trypan Blue assay (n = 2; P > .05). (B) MM.1R cells were treated with higher doses of plinabulin (20nM) for 1, 6, 16, and 24 hours, and Western blot analyses were performed with antibodies against pJNK, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, or GAPDH. CF indicates cleaved fragment. Results were representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (C top) MM.1R cells were treated with PAN caspase inhibitor for 2 hours, and then plinabulin (8nM) was added for an additional 48 hours. Protein lysate was prepared; phosphorylation of JNK was checked with Western blot analysis. (C bottom) MM.1R cells were pretreated with JNK inhibitor SP600125 (20μM, 2 hours), and plinabulin (8nM) was added for another 48 hours. After 48 hours protein lysate was prepared and cleaved caspase-3 expression was checked with Western blot analysis. (D) MM cell line MM.1S was pretreated with SP600125 (20μM) for 2 hours, and plinabulin (8nM) was added for an additional 16 hours followed by analysis for histone H3 phosphorylation with the use of flow cytometry. Data are representation of 3 independent experiments.

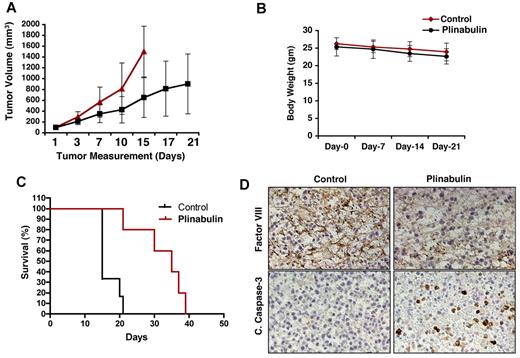

Plinabulin inhibits tumor growth in the human plasmacytoma xenograft mouse model

Having shown the in vitro anti-MM activity of plinabulin, we next examined in vivo efficacy of plinabulin with the use of human MM xenograft murine models. MM.1S tumor-bearing mice were treated with plinabulin (7.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally) or vehicle alone twice a week for 3 weeks. Plinabulin treatment inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in mice (Figure 7A,C; P < .05). Plinabulin treatment was well tolerated, without significant weight loss (Figure 7B). Importantly, increased survival was noted in mice receiving plinabulin versus vehicle alone (P = .0041); median survival in the control group was 15 days versus 35 days in the plinabulin treatment group (Figure 7C).

In vivo anti-MM activity of plinabulin. (A) MM.1S cells (5 × 106 in 100 μL of serum-free RPMI-1640 medium) were implanted subcutaneously in mice (7 mice/group); average and standard deviation of tumor volume (mm3) were monitored every third day. Mice were treated intraperitoneally with plinabulin (7.5 mg/kg) or vehicle alone twice weekly for 3 weeks. Bars indicate mean ± SD (P = .05). (B) Body weight of plinabulin-treated versus control mice was monitored once a week. Data show ± SD of 6 different mice/group. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival of mice treated with plinabulin compared with vehicle-treated controls. (D) Tumors from control and plinabulin-treated mice were subjected to immunostaining with antibodies against cleaved caspase-3 and factor VIII. Photographs are representative of similar observations in 2 different mice receiving the same treatment.

In vivo anti-MM activity of plinabulin. (A) MM.1S cells (5 × 106 in 100 μL of serum-free RPMI-1640 medium) were implanted subcutaneously in mice (7 mice/group); average and standard deviation of tumor volume (mm3) were monitored every third day. Mice were treated intraperitoneally with plinabulin (7.5 mg/kg) or vehicle alone twice weekly for 3 weeks. Bars indicate mean ± SD (P = .05). (B) Body weight of plinabulin-treated versus control mice was monitored once a week. Data show ± SD of 6 different mice/group. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival of mice treated with plinabulin compared with vehicle-treated controls. (D) Tumors from control and plinabulin-treated mice were subjected to immunostaining with antibodies against cleaved caspase-3 and factor VIII. Photographs are representative of similar observations in 2 different mice receiving the same treatment.

We next examined tumors from plinabulin-treated compared with control mice, and we performed immunostaining for cleaved caspase-3 and vasculature-related marker such as factor VIII. As shown in Figure 7D, increase in cleaved caspase-3 was observed in tumor sections from the plinabulin-treated group versus the control group (Figure 7D bottom). Moreover, antivascular activity of plinabulin was evidenced by a significant reduction in factor VIII expression (Figure 7D top). These results show that in vivo anti-MM activity of plinabulin is associated with disruption of tumor vasculature and proapoptotic activity.

Discussion

VDAs target the cytoskeleton and tubulin network of endothelial cells,31 thereby causing vascular disruption and subsequent tumor cell death.32-36 Previous studies have shown that plinabulin (NPI-2358) can inhibit microtubule depolymerization in proliferating HUVECs at much lower concentrations compared with colchicine.18,37 Similar to colchicine, plinabulin can inhibit polymerization of the microtubule, which is an important component of tubulin and essential for mitosis; therefore they are also known as mitotic poison or spindle poison. Microtubule-disrupting agents have the ability to induce structural changes in the microtubule cytoskeleton; therefore, they stop the cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest by activating the cell cycle checkpoint that can monitor the mechanics of mitotic spindle function.38,39 Mitotic arrest is the primary function for anti–microtubule agents and is responsible for cytotoxicity activity of several microtubule-disrupting agents. Cells that escape from mitosis lack both anaphase and cytokinesis, and they proceed to the G1 phase of the cell cycle.40,41 Several studies have shown that cells with an intact G1 checkpoint remain in the same state; however, cells with a defective G1 checkpoint undergo aberrant apoptosis or cell death.42

Similar to previously reported microtubule-disrupting agents, plinabulin also inhibits the proliferation of MM cells by triggering mitotic block as an early event, whereas apoptosis is a terminal event.12,33 Trans-well insert assays and tubule formation assays confirmed antitumor vasculature activity of plinabulin. Plinabulin did not affect viability of normal PBMCs, suggesting a favorable therapeutic index. In MM, adhesion of tumor cells to BMSCs trigger transcription and secretion of various cytokines mediating MM cell growth, survival, migration, and drug resistance2,30,43 ; importantly, plinabulin overcomes BMSC- or IL-6–induced MM cell growth.

Mechanistic studies showed that plinabulin-induced apoptosis is mediated through activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 and PARP cleavage. Plinabulin also triggers phosphorylation of the stress response protein JNK. Previous studies have shown that sustained JNK activation is associated with apoptosis induction, whereas transient JNK activation leads to cell survival.44-47 Microtubule-disrupting agents can induce JNK as a primary target in a variety of cancer cells by inhibiting the microtubule dynamic that helps cells to undergo apoptosis. Previous studies have shown that microtubule inhibitor can lead to proteasomal degradation of both cellular FLICE (FADD-like IL-1β–converting enzyme)–activating protein through mitotic arrest and JNK-dependent mechanism48 and trigger sustained activation of JNK in a variety of human cancer cells.49 In agreement with previously reported data, our result showed that JNK is activated very early in response to plinabulin treatment and is required for both mitotic arrest and apoptosis. Our results suggest that caspase and JNK both are required for plinabulin-induced cell death; however, JNK appears to be a primary target. Indeed, our results showed that pharmacologic blockade of JNK-I or JNK-II with SP600125 or genetic knockdown with the use of siRNA significantly blocked plinabulin-induced MM cell apoptosis, confirming an obligatory role for JNK during plinabulin-induced mitotic arrest and MM cell death.

In vivo studies showed that plinabulin significantly inhibits tumor growth and prolongs survival of mice receiving plinabulin compared with vehicle-treated controls. Importantly, favorable tolerability was observed in mice receiving plinabulin treatment, evidenced by < 10% weight loss. Analysis of tumor sections from plinabulin-treated mice showed increased apoptosis, assessed by cleaved-caspase-3 staining, associated with a marked antivascular activity, evidenced by reduction in factor VIII expression. At present, plinabulin is in phase 2 clinical trials in combination with docetaxel in patients with non–small cell lung cancer. 21,22 These in vitro and in vivo preclinical data now provide the framework for clinical trials of plinabulin to improve patient outcome in MM as well.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH (grants SPORE-P50100707, PO1-CA078378, and RO1CA050947) and MRF funds. K.C.A. is an ACS Clinical Research Professor.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: D.C. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; A.V.S. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.B. performed the experiments; N.R. and P.R. provided clinical samples; M.A.P. designed treatment approaches and provided plinabulin; and K.C.A. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.C.A. is a consultant to Nereus Pharmaceuticals Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kenneth C. Anderson, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Mayer Bldg Rm 561, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 0211; e-mail: kenneth_anderson@dfci.harvard.edu; or Dharminder Chauhan, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Mayer Bldg Rm 561, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 0211; e-mail: dharminder_chauhan@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

D.C. and K.C.A. are co–senior authors.