Whereas the chimeric type I anti-CD20 Ab rituximab has improved outcomes for patients with B-cell malignancies significantly, many patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) remain incurable. Obinutuzumab (GA101) is a glycoengineered, humanized anti-CD20 type II Ab that has demonstrated superior activity against type I Abs in vitro and in preclinical studies. In the present study, we evaluated the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of GA101 in a phase 1 study of 21 patients with heavily pretreated, relapsed, or refractory CD20+ indolent NHL. Patients received GA101 in a dose-escalating fashion (3 per cohort, range 50/100-1200/2000 mg) for 8 × 21-day cycles. The majority of adverse events (AEs) were grades 1 and 2 (114 of 132 total AEs). Seven patients reported a total of 18 grade 3 or 4 AEs. Infusion-related reactions were the most common AE, with most occurring during the first infusion and resolving with appropriate management. Three patients experienced grade 3 or 4 drug-related infusion-related reactions. The best overall response was 43%, with 5 complete responses and 4 partial responses. Data from this study suggest that GA101 was well tolerated and demonstrated encouraging activity in patients with previously treated NHL up to doses of 2000 mg. This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00517530.

Introduction

The chimeric anti-CD20 Ab rituximab has improved outcomes for patients with B-cell malignancies significantly over the past decade, and is now a standard treatment in combination with chemotherapy in both aggressive and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and as maintenance therapy in follicular lymphoma.1,,,,,–7 However, whereas significant advances in both progression-free and overall survival have been achieved, a significant number of patients with NHL remain incurable and develop rituximab-refractory disease.

Because the CD20 antigen, which is expressed on normal and malignant B cells, has proven to be such a highly successful target antigen for immunotherapeutic approaches, there has been considerable interest in novel anti-CD20 Abs with different functional activity from rituximab that might translate into improved efficacy. Studies of CD20 Abs that have been developed have used complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), and direct induction of cell death8 to various extents in in vitro assays. However, it remains unclear to what extent each mechanism is important to the therapeutic activity of the Ab. Based on mechanisms of action, anti-CD20 Abs can be divided into 2 types: type I, which have good CDC and ADCC activity but are relatively poor at inducing direct cell death; and type II, which have little CDC activity but are effective at inducing direct cell death.8,–10 In contrast to that caused by type I Abs, direct cell death induced by type II Abs has been observed to occur in the presence of antiapoptotic signals such as BCL-2.11 Type I and type II Abs can also be distinguished by their differing ability to reorganize CD20 into lipid rafts in the cell membrane; unlike type II Abs, type I Abs effectively translocate and stabilize CD20 in these rafts, and this appears to be important for their ability to activate complement.10

The majority of new anti-CD20 Abs (eg, rituximab) have been of the type I variety. These include veltuzumab,12 ocrelizumab,13 and ofatumumab.14 Obinutuzumab (GA101) was specifically designed as a type II Ab and is glycoengineered; the Fc region of the Ab is nonfucosylated, which gives it increased ADCC activity.15 The modifications in the GA101 structure were designed with the intention of providing an Ab with increased B cell–killing activity compared with rituximab and other type I anti-CD20 mAbs. Observations from in vitro studies suggest that GA101 is superior to type I Abs in inducing direct cell death of lymphoma cells,11,15 in ADCC induction, and in depleting B cells from whole human blood.16 GA101 also demonstrated increased antitumor activity compared with type I Abs in human tumor xenograft models, both as a single agent15,17 and in combination with chemotherapy,17 and has also been shown to deplete B cells from lymphoid tissues in nonhuman primates.15

Given the apparent superiority of GA101 over rituximab in preclinical studies, it is now being evaluated as a treatment for various hematologic malignancies. We report herein the safety and clinical activity of GA101 in a phase 1 dose-finding study of patients with heavily pretreated, relapsed, or refractory CD20+ NHL.

Methods

Patients

This was a multicenter, phase 1 study evaluating the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and clinical activity of escalating doses of single-agent GA101 in patients with relapsed/refractory NHL. The primary end point was safety. Approval was received from the independent ethics committee/independent review boards of all participating institutions before the study commenced.

Eligible patients were > 18 years of age with CD20+ B-cell lymphoma with at least one bidimensionally measurable lesion (> 1.5 cm), life expectancy > 12 weeks, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2. Eligible patients had disease with an indication for treatment for which no therapy of curative potential or of higher priority existed. Confirmation of CD20 positivity was provided by local biopsy before dosing and later by central review. Patients could not have received rituximab within 56 days of study entry, although for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma requiring immediate treatment, a rituximab washout period of 28 days was sufficient and considered on a case-by-case basis. Prior radioimmunotherapy within 3 months or administration of an investigational mAb or other agent within 6 months was also not permitted.

Patients were required to have adequate renal function (creatinine clearance > 50 mL/min) and liver function (alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase ≤ 2.5 × upper limit of normal) and appropriate hematologic parameters (platelets ≥ 75 × 109/L, neutrophils ≥ 1.5 × 109/L, and hemoglobin 10 g/dL unless due to lymphoma).

Patients with known active bacterial or viral infections or with positive serologic tests for hepatitis B (surface or core antigen), hepatitis C, or HIV were excluded.

All patients gave written informed consent, including consent for genotyping of Fcγ receptors, before study participation.

Treatment

Patients were treated in dose cohorts of 3 patients each and received GA101 IV as a flat dose in a dose-escalating fashion for 8 × 21-day cycles. Because no dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) occurred with either the first or subsequent administrations, dose escalation was continued through 7 cohorts. The first 4 cohorts received 50% of the scheduled dose in the first infusion (50/100 mg, 100/200 mg, 200/400 mg, or 400/800 mg) and the full assigned dose for the remaining 8 infusions in the absence of severe infusion-related reactions (IRRs). In the absence of DLTs, cohorts 5 and 6 were adjusted to 800/1200 mg and 1200/2000 mg. Based on early pharmacokinetic data suggesting rapid elimination of the Ab after the first administration, cohort 7 received a “loading” dose of 1600 mg on day 1 and day 8 of the first cycle and 800 mg in subsequent cycles.

Infusions were given on days 1 and 8 of the first cycle and on day 1 of subsequent cycles for a total of 9 infusions. Patients were premedicated with diphenhydramine and acetaminophen, and corticosteroids were permitted at investigator discretion for patients with a large tumor burden, previous severe reactions to rituximab, or severe IRRs observed with the first GA101 infusion. For administration, GA101 was diluted to 10 mg/mL and administered at an initial rate of 50 mg/h. In the absence of IRRs, the rate could be increased in increments of 50 mg/h every 30 minutes to a maximum of 400 mg/h.

Assessments

A full clinical history and clinical and biologic evaluation, including blood counts, differential serum chemistry, and renal and hepatic function, were carried out at screening, with subsequent safety assessments on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1 and on day 1 of subsequent treatment cycles. Serial serum samples were taken during cycles 1 and 8 for assessment of GA101 concentrations and other variables, such as complement and cytokine levels, by ELISA and cytometric bead arrays. Samples were also taken before and after dose for all cycles. CD19+ cells in the peripheral blood were assessed by flow cytometry at cycles 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 and every 3 months during follow-up. DNA was extracted from pretreatment blood samples for genotype analysis of Fcγ receptors. Patients were assessed for clinical response after 4 and 8 cycles of GA101 (12 and 24 weeks from study entry) according to standardized response criteria for NHL.18

DLTs

DLTs were defined as any grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event (AE) within the first 28 days of treatment other than lymphopenia, neutropenia that did not result in febrile neutropenia and resolved to grade 2 or lower within 2 weeks, and thrombocytopenia that did not result in bleeding and resolved to grade 2 or lower within 2 weeks.

In addition, infusion-related DLTs (first infusion only) were defined as any grade 4 infusion-related toxicity or any grade 3 infusion-related toxicity that could not be resolved by infusion rate reduction, dose interruption/discontinuation, or supportive care.

If 2 or more patients within a cohort experienced infusion-related DLTs with the first infusion, dose escalation for the first infusion was stopped and the maximum tolerated dose for the first infusion was established from the previous cohort. If 2 or more patients within a cohort experienced DLTs with subsequent doses, the overall maximum tolerated dose was established and dose escalation was stopped.

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 21 patients were recruited to 7 dose cohorts. Lymphoma subtypes were follicular (n = 13), mantle cell (n = 4), diffuse large B cell (n = 1), small lymphocytic (n = 1), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (n = 1), and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (n = 1). Patients had received a median of 5 (range, 1-8) prior therapies. All but 1 patient had received rituximab previously (Table 1).

Patient demographics

| Characteristic . | N = 21 . |

|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 9/12 |

| Median age, y (range) | 64 (39-83) |

| Median time from diagnosis, y (range) | 5.9 (2.5-24.2) |

| Median prior therapies, n (range) | 5 (1-8) |

| Prior rituximab, n (%) | 20 (95) |

| Rituximab-refractory, n (%) | 9 (43) |

| Prior ASCT, n (%) | 6 (29) |

| Prior fludarabine, n (%) | 5 (24) |

| Median duration of response to last treatment, mo (range) | 16 (3-112) |

| Baseline hematologic parameters, median (range) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 123 (75-151) |

| Neutrophils, 109/L | 3.27 (1.59-8.28) |

| Platelets, 109/L | 172 (73-325) |

| Characteristic . | N = 21 . |

|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 9/12 |

| Median age, y (range) | 64 (39-83) |

| Median time from diagnosis, y (range) | 5.9 (2.5-24.2) |

| Median prior therapies, n (range) | 5 (1-8) |

| Prior rituximab, n (%) | 20 (95) |

| Rituximab-refractory, n (%) | 9 (43) |

| Prior ASCT, n (%) | 6 (29) |

| Prior fludarabine, n (%) | 5 (24) |

| Median duration of response to last treatment, mo (range) | 16 (3-112) |

| Baseline hematologic parameters, median (range) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 123 (75-151) |

| Neutrophils, 109/L | 3.27 (1.59-8.28) |

| Platelets, 109/L | 172 (73-325) |

ASCT indicates autologous stem cell transplantation.

Refractory is defined as progression on treatment, stable disease, or partial response or better with progression < 6 months after any prior rituximab-containing therapy.

Analysis populations

All 21 patients recruited to the study received at least 1 dose of GA101 and were included in both the safety and efficacy analyses.

Safety and tolerability

All patients experienced at least 1 AE during the course of the study. AEs were distributed evenly across dose groups, with no evidence of a dose-effect relationship. A summary of AEs is shown in Table 2. The majority of AEs were grade 1 and 2 (114 of 132 total AEs, 86%), with only 7 patients (33%) reporting a total of 18 grade 3 or 4 AEs. All related grade 4 events were neutropenias, and the majority of grade 3 events were hematologic toxicities and IRRs.

All Grade 3 or 4 AEs and additional AEs (all grades) occurring in more than 1 patient

| AE . | All grades . | Grade 3 or 4 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | No. of events . | n . | % . | No. of events . | |

| Any AE | 21 | 100 | 132 | 7 | 33 | 18 |

| Infusion-related reactions | 18 | 86 | 48 | 2 | 10 | 3 |

| Cycle 1, day 1 (n = 21) | 17 | 81 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Cycle 1, day 8 (n = 20) | 8 | 40 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Cycle 2 (n = 19) | 5 | 26 | ||||

| Cycle 3 or later (n = 16) | 6 | 38 | ||||

| Infections* | 11 | 52 | 16 | |||

| Asthenia | 8 | 38 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 24 | 7 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Anorexia | 4 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Weight loss | 4 | 19 | 4 | |||

| Lymphopenia | 3 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 3 | 14 | 3 | |||

| Nausea | 3 | 14 | 3 | |||

| Insomnia | 3 | 14 | 3 | |||

| Neutropenia | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| Anemia | 2 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Sciatica | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Extrinsic vascular compression | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Leukopenia | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Axillary pain | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular accident† | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||

| AE . | All grades . | Grade 3 or 4 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | No. of events . | n . | % . | No. of events . | |

| Any AE | 21 | 100 | 132 | 7 | 33 | 18 |

| Infusion-related reactions | 18 | 86 | 48 | 2 | 10 | 3 |

| Cycle 1, day 1 (n = 21) | 17 | 81 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Cycle 1, day 8 (n = 20) | 8 | 40 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Cycle 2 (n = 19) | 5 | 26 | ||||

| Cycle 3 or later (n = 16) | 6 | 38 | ||||

| Infections* | 11 | 52 | 16 | |||

| Asthenia | 8 | 38 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 24 | 7 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Anorexia | 4 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Weight loss | 4 | 19 | 4 | |||

| Lymphopenia | 3 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 3 | 14 | 3 | |||

| Nausea | 3 | 14 | 3 | |||

| Insomnia | 3 | 14 | 3 | |||

| Neutropenia | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| Anemia | 2 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Sciatica | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Extrinsic vascular compression | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Leukopenia | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Axillary pain | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular accident† | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||

The most common infection reported was bronchitis (n = 4). Herpesvirus infection occurred in 2 patients. All reported infections were grade 1 or 2.

The incidence of cerebrovascular accident was grade 5 and resulted in death. This 83-year-old patient had a low IgM level before treatment (115 mg/dL). IgM levels increased to 404 mg/dL after cycle 1, but returned to 107 mg/dL after cycle 2, 34 days before the cerebrovascular accident. Although no disease evaluation or IgM measurement was available before death, given this kinetic and the patient's underlying illness, the investigator judged that this event was unrelated to the study drug.

IRRs were the most frequently reported AEs, with a total of 18 of 21 patients (86%) experiencing an IRR (Table 3). The majority (98%) of IRRs were limited to grade 1 or 2; no grade 4 IRRs were observed. Most IRRs were observed during the first infusion and resolved with slowing or interruption of the infusion and/or steroid administration, with patients ultimately able to receive their full dose. The most common IRRs, experienced by more than 3 patients, were hypotension (52%), pyrexia (48%), nausea (43%), vomiting (38%), chills (29%), asthenia (29%), flushing (14%), headache (14%), and larynx irritation (14%). Three patients (14%) experienced drug-related (investigator-assessed) grade 3 or 4 AEs during or within 24 hours of completion of infusion, comprising 2 IRRs and 1 case each of anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and tumor lysis syndrome that resolved with appropriate management. Two patients had treatment-related grade 3 neutropenia that appeared at days 65 and 127 and recovered within 12 and 34 days, respectively, without the need for supportive treatment with G-CSF. Grade 3 serious thrombocytopenia was reported in 1 patient on day 1 of the study, which resolved without further sequelae after platelet transfusion. Only 2 patients had received steroids before their first infusion of GA101; 1 patient (with elevated WBC counts) experienced a tumor lysis syndrome and the other patient did not experience an IRR.

Symptoms of infusion-related reactions and other drug-related AEs, listed by frequency, experienced by 3 or more patients during infusion and within 24 hours after completion of infusion (N = 21)

| AE . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least 1 AE | 18 | 86 |

| Hypotension* | 11 | 52 |

| Pyrexia | 10 | 48 |

| Nausea* | 9 | 43 |

| Vomiting* | 8 | 38 |

| Chills* | 6 | 29 |

| Asthenia | 6 | 29 |

| Flushing | 3 | 14 |

| Headache | 3 | 14 |

| Larynx irritation | 3 | 14 |

| AE . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least 1 AE | 18 | 86 |

| Hypotension* | 11 | 52 |

| Pyrexia | 10 | 48 |

| Nausea* | 9 | 43 |

| Vomiting* | 8 | 38 |

| Chills* | 6 | 29 |

| Asthenia | 6 | 29 |

| Flushing | 3 | 14 |

| Headache | 3 | 14 |

| Larynx irritation | 3 | 14 |

One patient experienced grade 3 hypotension, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness that resulted in the dosage being modified. Other grade 3 events were observed in a mantle cell lymphoma patient who experienced tumor lysis syndrome; events included asthenia, chills, dyspnea, headache, hyperkalemia, hyperthermia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. No grade 4 infusion-related events were observed.

Eleven patients (52%) had at least 1 infusion modification, comprising slowing down of infusion (8 patients) and interruption of the infusion (3 patients). The time taken for infusion varied widely depending on the dose infused and whether modifications were required. The 50- and 100-mg doses could often be infused in less than 50 minutes, whereas for the 2000-mg dose, at least 6 hours and frequently longer periods were required.

Serious AEs were reported for 3 patients (14%), 1 in the 50/100-mg dose group (a fatal cerebrovascular accident in an 83-year-old male patient with Waldenström macroglobulinemia who had low serum IgM levels and was not considered treatment-related by the investigator; see the legend to Table 2 for more details) and 2 in the 1200/2000-mg dose group (1 patient with renal colic and 1 with an IRR, thrombocytopenia, and tumor lysis syndrome). Ten patients withdrew from the study before receiving all 8 scheduled cycles. Reasons for withdrawal were: insufficient response or disease progression (n = 7), investigator decision (n = 1), administrative reasons (n = 1), or death (n = 1). There were no withdrawals for toxicity.

Immunologic parameters

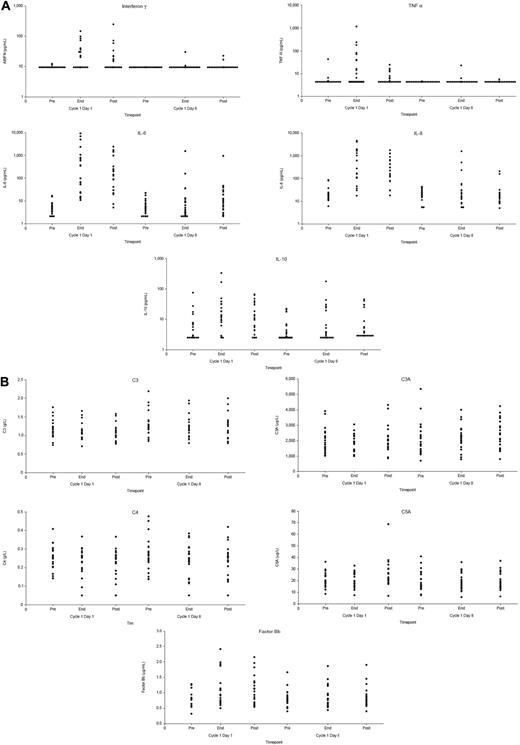

Peripheral B-cell counts were assessed at a central laboratory; the lower limit of normal range was 0.08 × 109/L. The majority of patients had low peripheral B-cell counts at baseline (median CD19+ B-cell count, 0.055 × 109/L), as might be expected from the effects of previous therapy. Treatment with GA101 was associated with a further lowering of B-cell counts, with 19 of 21 patients having CD19+ B cells lower than 0.04 × 109/L by the second infusion. At current limited follow-up (patients only in follow-up until progressive disease/new antilymphoma treatment), B-cell recovery to at least 0.08 × 109/L (investigator reference range, 0.080-0.616 × 109/L) has been observed in 1 patient, with recovery observed at day 409; most of the other patients progressed or received further treatment before B-cell recovery. Elevated cytokine levels were observed after the first infusion, becoming less common with subsequent infusions (Figure 1A). With only 1 patient presenting a grade 3 IRR, a correlation between cytokine release and the severity of the observed IRRs could not be established. No significant changes in serum levels of complement fractions were observed during or after infusion (Figure 1B). For the 9 patients for whom these data were available, no clinically significant changes in IgA, IgG, and IgM levels were observed when assessed 4 or more months after treatment was completed compared with pretreatment (data not shown).

Levels of cytokines and complement fractions before and after infusion of GA101. (A) Levels of cytokines (IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10). (B) Levels of complement fractions (C3, C3a, C4, C5b, and Bb). Levels were assessed 1 hour before infusion, at the end of infusion, and 2.5 hours after infusion. Each circle represents a single data point.

Levels of cytokines and complement fractions before and after infusion of GA101. (A) Levels of cytokines (IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10). (B) Levels of complement fractions (C3, C3a, C4, C5b, and Bb). Levels were assessed 1 hour before infusion, at the end of infusion, and 2.5 hours after infusion. Each circle represents a single data point.

Pharmacokinetics

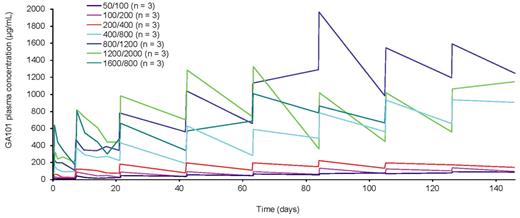

Serum obinutuzumab concentrations increase as dose increases; however, for the 3 lower-dose cohorts (50/100, 100/200, and 200/400 mg), the serum concentrations stayed persistently below 200 μg/mL and the increases in concentration were small. After doses of 400/800 mg and higher, there were substantial increases in serum obinutuzumab concentrations compared with the lower doses and a tendency for serum concentrations to increase over the treatment course (Figure 2).

Mean GA101 serum concentration-time profile. Each curve represents the mean of the cohort.

Mean GA101 serum concentration-time profile. Each curve represents the mean of the cohort.

Efficacy

One of the 21 patients died before having a response assessment and was considered a nonresponder for purposes of efficacy analysis. The response rate at the end of treatment (defined as 28 days from the last GA101 infusion) was 33% (4 complete responses [CRs] or unconfirmed CRs [CRu's] and 3 partial responses [PRs]). One patient had a transient PR midtreatment and progressed before the end of treatment, and 2 patients had an improvement in tumor response after the end of treatment (1 patient from stable disease [SD] to PR at day 562 and 1 patient from PR to CR at day 256). Nine patients achieved a response over time (best overall response rate was 43%), with 5 being CR/CRu (24%) and 4 PR (19%). Responses occurred in all dose groups, with no evidence of a dose-response relationship (Table 4).

Response by dose group (best overall response)

| . | GA101 dose (mg) . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50/100 (n = 3) . | 100/200 (n = 3) . | 200/400 (n = 3) . | 400/800 (n = 3) . | 800/1200 (n = 3) . | 1200/1200 (n = 3) . | 1600/1600/ 800 (n = 3) . | All (N = 21) . | |

| CR/CRu* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| PR†‡ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| SD | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| PD | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Death | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| . | GA101 dose (mg) . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50/100 (n = 3) . | 100/200 (n = 3) . | 200/400 (n = 3) . | 400/800 (n = 3) . | 800/1200 (n = 3) . | 1200/1200 (n = 3) . | 1600/1600/ 800 (n = 3) . | All (N = 21) . | |

| CR/CRu* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| PR†‡ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| SD | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| PD | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Death | 1 | 1 | ||||||

PD indicates progressive disease.

One patient with PR at the end of treatment later converted to CR.

One patient with PR after 4 cycles of treatment experienced disease progression before the end of treatment (8 cycles).

One patient who was stable at the end of treatment later converted to PR.

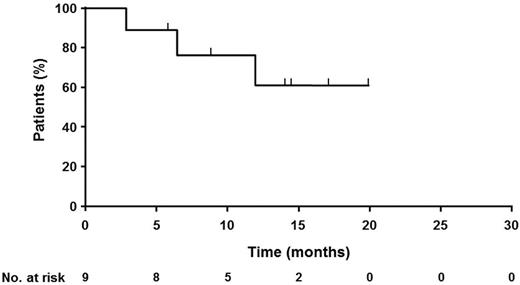

All responding patients were from the follicular lymphoma subgroup, giving a best overall response rate for follicular lymphoma of 69% (9 of 13 patients) with 38% CR (5 patients). Two of the 9 rituximab-refractory patients responded. The end-of-treatment response rate for follicular lymphoma was 54% (n = 7) with 31% CR (n = 4). One patient also had a late response, converting from SD to PR after 17 months in SD. Of the 4 mantle cell lymphoma patients, 2 progressed during treatment, 1 had a short-lived improvement in tumor load and progressed immediately after the end of therapy, and 1 had lasting SD for 1 year after study entry. Time-to-event data are immature, but 5 of the responding patients have an ongoing response, with the duration of response ranging from 5 months to more than 21 months (Figure 3).

Response duration in 9 responding patients. The curve shows duration of response for the 9 responding patients.

Response duration in 9 responding patients. The curve shows duration of response for the 9 responding patients.

As shown in Table 5, responses were observed in patients with all Fcγ receptor genotypes, including in 5 of 10 patients carrying the low-affinity FF isoform of FcγR IIIa. Because of the limited patient numbers, it was not possible to determine a correlation between the observed IRRs and Fcγ receptor genotype.

Response by FcγR polymorphisms (best overall response)

| . | FcγR IIa . | FcγR IIIa . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (n = 7) . | HH (n, 5) . | RR (n = 5) . | FF (n = 10) . | VV (n = 3) . | FV (n = 4) . | |

| Responder, n (%) | 2 (29) | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 5 (50) | 2 (67) | 1 (25) |

| Nonresponder, n (%) | 5 (71) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 5 (50) | 1 (33) | 3 (75) |

| . | FcγR IIa . | FcγR IIIa . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (n = 7) . | HH (n, 5) . | RR (n = 5) . | FF (n = 10) . | VV (n = 3) . | FV (n = 4) . | |

| Responder, n (%) | 2 (29) | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 5 (50) | 2 (67) | 1 (25) |

| Nonresponder, n (%) | 5 (71) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 5 (50) | 1 (33) | 3 (75) |

Response was defined as CR/CRu or PR; nonresponse was defined as progressive disease or SD. FcγR polymorphism data were available for 20 patients.

Discussion

This phase 1 study has demonstrated that GA101 can be administered in patients with previously treated B-cell lymphoid malignancies up to doses of 2000 mg. GA101 had an acceptable safety profile in this limited number of patients. The most common AEs were IRRs, which were predominantly associated with the first infusion and resolved with appropriate management. Symptoms mainly comprised fever, chills, and rigors. Other symptoms included flushing, angioedema, bronchospasm, vomiting, nausea, urticaria/rash, fatigue, headache, throat irritation, rhinitis, pruritus, pain, tachycardia, hypertension, hypotension, dyspnea, dyspepsia, asthenia, and features of tumor lysis syndrome. Grade 3/4 IRRs occurred in 10% of patients. Previous studies have reported elevated cytokine levels with rituximab infusion and an association between cytokine release and IRRs and other clinical symptoms such as fever, chills, and nausea.19,20 In the present study, elevated cytokine levels were observed after the first infusion, becoming less common with subsequent infusions. Correspondingly, the majority of IRRs were seen with the first infusion. The lack of complement activation did not prevent the occurrence of IRRs; however, with the low patient numbers, it was not possible to correlate cytokine release and severity of the observed IRRs. All patients who had received rituximab previously had a low lymphocyte count, which could reduce the rate of IRRs. Most AEs were mild to moderate in intensity, with only 7 patients experiencing any grade 3 or 4 toxicity and none experiencing grade 3 or 4 infections. The only patient experiencing a serious AE directly related to treatment (tumor lysis syndrome and thrombocytopenia after the first infusion) had mantle cell lymphoma, presented a rapid clearance of circulating lymphoma cells, and was then able to continue to receive GA101. That patient achieved a PR and was retreated with GA101 1 year later after a relapse. IRR was reported after the first dose of the second GA101 course of treatment; the patient received all 8 planned doses. One death due to cerebrovascular accident in an 83-year-old male patient with Waldenström macroglobulinemia was reported during treatment. Although this was not to be considered treatment related by the investigator, it cannot be excluded that the death could have been a result of a transient increase in serum IgM levels, which has been reported previously by patients during treatment with rituximab. In studies of rituximab in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia, transient increases in serum IgM levels have been observed after treatment initiation, which may be associated with hyperviscosity and related symptoms. The transient IgM increase usually returned to at least baseline level within 4 months. No DLTs were identified.

The present phase 1 study also shows encouraging activity for GA101 in 21 patients with heavily pretreated NHL. The best overall response rate was 43%, with 5 classified as CR/CRu. All responses were in follicular NHL, with 9 of 13 patients (69%) responding and 5 (38%) achieving a CR/CRu. The numbers of patients with other lymphoma subtypes was very small, so no conclusions regarding efficacy in these malignancies can be drawn in this phase 1 study. Responses (including CR) were observed in all dose cohorts, and there was no evidence for a dose-response effect in either safety profile or efficacy. Given the heterogeneity of the patient population in this study and the small patient numbers within each cohort, a relationship between dose and efficacy or safety cannot be discounted at this stage.

All doses of GA101 resulted in rapid depletion of B cells from the circulation, as expected. Patients treated with 4 infusions of rituximab generally achieve B-cell recovery within 6-12 months of the end of treatment.21 Data are too immature and variable to draw any conclusions about the length of B-cell depletion or time of recovery after up to 9 infusions of GA101 treatment.

Analysis of pharmacokinetic data indicated that, at lower doses (200/400 mg and below), obinutuzumab serum concentrations remain low, whereas after higher doses (400/800 mg and upwards), serum concentrations are substantially higher and accumulate over the treatment period. These data indicate that doses of at least 400/800 mg are required to fully saturate the target,22 and that target-mediated drug disposition may contribute significantly to the clearance of obinutuzumab at lower doses, whereas once the target is saturated the impact of this mechanism is minimized.

Through glycoengineering and its type II characterization, GA101 has been designed specifically to have both increased ADCC and direct cell death activity compared with rituximab. Consistent with its activity as a type II Ab, GA101 did not appear to activate the complement cascade, and no depletion of complement components was observed after infusion. The clinical activity is therefore presumably a result of ADCC and direct cell death induction, indicating a therapeutically important role for these mechanisms in therapeutic activity of anti-CD20 Abs. Previous data have indicated that FcγRIIIa gene polymorphism can influence rituximab activity.23 This dose-escalation study in a limited number of patients does not provide the best opportunity to further explore response variability according to FcγRIIIA polymorphism, and larger cohorts are required for such analysis to assess the hypothesis that glycoengineering of GA101 may overcome this variability.

The safety profile and efficacy observations from the present study are consistent with those reported for other anti-CD20 Abs, such as ofatumumab and ocrelizumab, when used in this patient population.13,14 The data from this phase 1 study show that this new type II glycoengineered Ab was well tolerated and offered encouraging activity, particularly in patients with follicular lymphoma. The phase 2 part of the current study is comparing 2 doses of GA101 (1600/800 vs 400/400 mg) in patients with relapsed/refractory indolent NHL. The current data support the continuation of GA101 development in phase 2, direct comparison with rituximab in the clinical setting, and studies in combination with chemotherapy. These studies are ongoing and will determine the role of GA101 in improving treatment options for patients with hematologic malignancies.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript, furnished by John Carron, PhD, was provided by F. Hoffmann–La Roche. The authors thank Elizabeth Wassner Fritsch for her contribution to the study.

Authorship

Contribution: G.S., F.M., T.L., N.M., C.T., H.T., and G.C. collected the data; G.S., F.M., T.L., N.M., C.T., H.T., G.B., D.C., and G.C. analyzed and interpreted the data; E.A. analyzed and interpreted the data and performed the statistical analysis; and all authors contributed intellectually to the development of this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.S. and G.C. have all received consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann–La Roche. G.S., F.M., N.M., and G.C. have all received honoraria from F. Hoffmann La–Roche. G.B., E.A., D.C., J.B., and P.P. were all employees of F. Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd at the time of the study. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Professor Gilles Salles, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Université Claude Bernard, UMR CNRS5239, Centre Hospitalier Lyon-Sud, 69310 Pierre-Bénite, France; e-mail: gilles.salles@chu-lyon.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal