Key Points

IL-3 receptor α (CD123) expression is elevated in CML progenitor and stem cells compared with healthy donors.

CD123 monoclonal antibody targeting represents a novel, potentially clinically relevant approach to deplete CML progenitor and stem cells.

Abstract

Despite the remarkable efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in eliminating differentiated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells, recent evidence suggests that leukemic stem and progenitor cells (LSPCs) persist long term, which may be partly attributable to cytokine-mediated resistance. We evaluated the expression of the interleukin 3 (IL-3) receptor α subunit (CD123), an established marker of acute myeloid leukemia stem cells, on CML LSPCs and the potential of targeting those cells with the humanized anti-CD123 monoclonal antibody CSL362. Compared with normal donors, CD123 expression was higher in CD34+/CD38– cells of both chronic phase and blast crisis CML patients, with levels increasing upon disease progression. CSL362 effectively targeted CML LSPCs by selective antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)–facilitated lysis of CD123+ cells and reduced leukemic engraftment in mice. Importantly, not only were healthy donor allogeneic natural killer (NK) cells able to mount an effective CSL362-mediated ADCC response, but so were CML patients’ autologous NK cells. In addition, CSL362 also neutralized IL-3–mediated rescue of TKI-induced cell death. Notably, combination of TKI- and CSL362-induced ADCC caused even greater reduction of CML progenitors and further augmented their preferential elimination over normal hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Thus, our data support the further evaluation of CSL362 therapy in CML.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is characterized by the reciprocal chromosomal translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) resulting in the formation of the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph). This encodes the constitutively active Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, which profoundly affects proliferation, apoptosis, and cell adhesion signaling pathways.1,2 The majority of patients are diagnosed in chronic phase (CP), showing an expansion of myeloid lineage cells that are maintained by a rare subset of CD34+/CD38– leukemic stem cells (LSCs).1,2 Refractoriness of these LSCs to therapy may result in progression to blast crisis (BC). BC-CML is characterized by differentiation arrest and a disease more akin to that of an acute leukemia.1,2

CML evolved as a paradigm for targeted therapy because treatment with imatinib, a small-molecule Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), significantly improved the estimated overall survival in CP-CML patients to 85% at 8 years.3 Furthermore, more potent second-generation TKIs, such as nilotinib4 and dasatinib,5 induce faster and higher major molecular response (MMR) rates. Nevertheless, LSCs are thought to be insensitive to TKI therapy6,7 and persist in CML patients, even in those with sustained complete molecular response (CMR).8,9 This is supported by the observation of molecular relapse after cessation of imatinib in 61% to 66% of CML patients, previously in CMR.10,11 Thus, current research efforts aim to develop additional therapies to target these TKI-refractory CML LSCs.

In addition to other proposed mechanisms, we and others have previously shown that cytokine-induced Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) survival signaling potently mediates resistance to TKIs in CML CD34+ progenitors.12-14 Also, CML CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– cells are thought to produce interleukin (IL) 3 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) providing an autocrine activation loop that contributes to their innate resistance.15-17 Accordingly, the concept of targeting CML leukemic stem and progenitor cells (LSPCs) at the cytokine receptor level might be a promising approach, especially because some cytokine receptors are overexpressed in stem cells of certain leukemias. One example is CD123 (IL-3 receptor α subunit), an established LSC marker in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).18,19 However, in CML, cell surface markers that distinguish normal and LSCs remain elusive.

The IL-3 receptor consists of a ligand-binding α subunit (CD123) and the primary signaling subunit βc (CD131).20,21 IL-3 signaling is known to stimulate cell cycle progression in early hematopoietic progenitors and promote differentiation while inhibiting apoptosis in various hematopoietic cells.20,21 CD123 advanced as a promising therapeutic monoclonal antibody (mAb) target in AML because treatment with the IL-3–neutralizing antibody 7G322 reduced AML LSC homing, engraftment, and self-renewal ability and improved the survival of xenografted NOD/SCID mice with minimal effect on the engraftment of normal bone marrow (BM) cells.23 This prompted the clinical development of CSL362, a humanized form of 7G3, which was additionally Fc-engineered to achieve maximal antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).24

Here we show that, compared with normal donors, CD123 expression is significantly increased in CD34+/CD38– cells of both CP- and BC-CML patients and that CSL362 is highly effective in blocking IL-3–stimulated rescue of TKI-induced cell death and mediating ADCC in CML LSPCs. To our knowledge, this is the first report to investigate CD123 mAb targeting to eliminate CML LSPCs.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Peripheral blood and BM samples of normal donors, CML patients (patient characteristics in supplemental Table 1; available on the Blood Web site), and AML patients were obtained after informed consent in accordance with protocols approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Adelaide Hospital and the Declaration of Helsinki. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated by Ficoll (Lymphoprep, Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) density gradient centrifugation.

CD34+ and natural killer (NK) cell isolation

CD34+ cells were isolated from MNCs by magnetically activated cell sorting using the human CD34 progenitor kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). Cryopreservation and subsequent thawing and resting (1 hour at 37°C) of isolated CML CD34+ cells ensured high purity (>85%). The human NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech) was used to isolate CML patients’ and normal donors’ NK cells by magnetically activated cell sorting.

Cell lines

MOLM-1 megakaryoblastic CML cells25 and TF-1.8 erythroleukemia cells, lentivirally transduced to overexpress CD123 and green fluorescent protein (GFP), were cultured in RPMI/10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and RPMI/10% FCS supplemented with 2 ng/mL granulocyte macrophage–CSF (GM-CSF), respectively, at 37°C/5% CO2. The murine stromal cell line AFT024,26 a kind gift of I. D. Lewis, Department of Haematology, SA Pathology, Adelaide, Australia, was cultivated at 33°C/5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/10% FCS/0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol.

Reagents

CSL36224 and the corresponding IgG1 isotype control antibody BM4 were produced by CSL Limited, Parkville, Australia. Dasatinib and nilotinib were purchased from Symansis (Timaru, New Zealand). Recombinant cytokines were from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ), and insulin (Actrapid; Novo Nordisk, Denmark) and hydrocortisone (Solucortef; Pfizer, New York, NY) were from the Royal Adelaide Hospital Pharmacy Department. All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Flow cytometry

Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies for cell surface staining were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA; CD3, CD16, CD34, hCD45, CD56, and CD123), Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA; mCD45), and BioLegend (San Diego, CA; CD38). To determine STAT5 phosphorylation in CML LSPCs, CD34+ cells, treated as indicated, were fixed and permeabilized as described12 and costained with BD Phosflow pY694 STAT5-Alexa 488, CD34-PE, and CD38-Alexa 647. Data were acquired on an FC500 (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) and analyzed using FCS Express (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA). CP-CML CD34+/CD38lo subpopulations were sorted on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Aria (BD Biosciences).

Cell viability assay

CML CD34+ cells, treated as indicated, were cultured for 72 hours in serum-deprived medium, containing Iscove Modified Dulbecco Medium supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 U/mL insulin, 0.2 mg/mL iron-saturated transferrin, 20 µg/mL low-density lipoproteins, and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Cells were labeled with Annexin V-phycoerythrin (PE) (BD Biosciences) and 7-Aminoactinomycin D (Invitrogen) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Double-negative populations defined viable cells.

Colony-forming unit (CFU) assay

CD34+ cells, pretreated as indicated, or sorted cell populations were plated in Methocult H4230 Medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), containing 20 ng/mL of GM-CSF, G-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, and 50 ng/mL of stem cell factor. CFU–granulocyte and macrophage and spontaneous burst-forming unit–erythroid colonies were counted after 14 days. To determine the replating capability, all colonies per dish were harvested and washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline, and 104 cells were replated into fresh methylcellulose culture medium. Secondary colonies were counted after a further 14-day incubation.

Long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) assay

CD34+ cells, pretreated as indicated, were plated in duplicates on AFT024 feeder cell layers (irradiated with 20 Gy) established in 24-well plates in MyeloCult H5100 (Stem Cell Technologies) freshly supplemented with 10−6 M hydrocortisone. Cultures were maintained for 5 weeks at 37°C with weekly half-media changes, before seeding harvested cells into CFU assays.

CFSE proliferation assay

To assess proliferation, CP-CML CD34+ cells were labeled with 1 µM 5- (and 6-) carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Cell Trace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit, Invitrogen) prior to drug treatment of 72 hours and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry. Data were fitted using the FCS Express proliferation module (De Novo Software).

ADCC assay

Target cells (CD34+ cells or CD123+ cell lines), pretreated with CSL362 (15 minutes), were incubated with purified NK cells at an effector to target cell ratio (E:T) of 10:1 for 4 hours at 37°C in RPMI/5% FCS. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was measured using the CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI), and the percentage of specific antibody-mediated target cell lysis was calculated by subtracting spontaneous lysis. Remaining CFUs and LTC-ICs were enumerated, and CD123 expression was determined by flow cytometry. For combination experiments with nilotinib, effector and target cells were incubated at a ratio of 1:1 overnight with 0.5 ng/mL IL-2.

Murine engraftment studies

Mice were maintained using protocols and conditions approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of SA Pathology/Central Health Network. Transplantation of human cells into female NOD/SCID (NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J) mice was performed as previously described.23 Briefly, thawed BC-CML MNCs (5 × 106 per mouse) were incubated with CSL362 or BM4 isotype control antibody (1 µg/mL) in the presence of purified NK cells (E:T 1:1), with or without 1 µM nilotinib, overnight at 37°C in RPMI/5% FCS before tail vein injection into sub-lethally irradiated (275 cGy) mice. Engraftment was measured at 12 weeks by flow cytometric quantification of the proportion of human vs total (human and murine) CD45+ cells.27 BCR-ABL1 quantitative polymerase chain reaction28 was performed on total BM of all mice, whereas fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was only done if the engraftment exceeded 1%.

FISH

FACS-sorted cells or CFUs, plucked and washed in phosphate-buffered saline, were left to adhere to slides pretreated with poly-l-lysine (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) before fixation in ice-cold Carnoy’s fixative (methanol:acetic acid 3:1). Hybridization using the XL BCR/ABL1 plus dual fusion probe (MetaSystems, Altlussheim, Germany) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. At least 100 nuclei were scored per sample.

IL-3 plasma levels

IL-3 plasma levels were determined using a Human Cytokine Milliplex bead array assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and a Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex, Austin, TX).

Statistical analysis

Graphpad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for graphs, and data are presented as mean ± standard error or individual data points. Statistical analysis was performed in Sigma plot (San Jose, CA), and Student t tests or Mann-Whitney tests were used as required.

Results

CML CD34+/CD38– cells express elevated levels of CD123

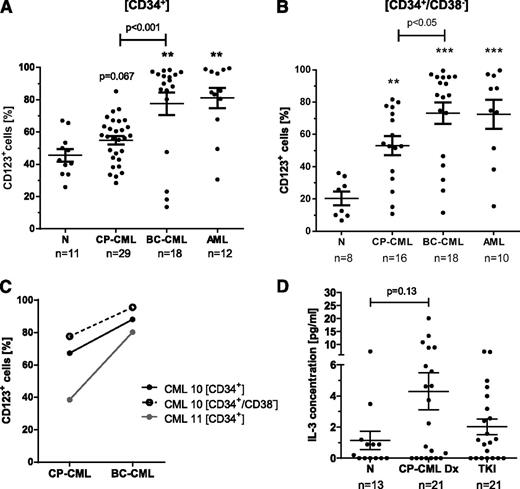

BC-CML CD34+ cells showed a higher frequency of CD123+ cells (77.5% vs 45.5%; P = .007) and an increase in CD123-PE mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; 7.3 vs 2.3; P = .001) compared with normal CD34+ cells, and in CD34+ cells from CP-CML patients, a trend toward increased CD123 expression was detected (Figure 1A; gating demonstrated in supplemental Figure 1). In the CD34+/CD38– subset, which is enriched for LSCs, the percentage of CD123+ cells and CD123 expression levels were significantly elevated (P < .01) in samples of both de novo CP-CML (53.0% CD123+/MFI 2.4) and BC-CML patients (73.2% CD123+/MFI 8.9) compared with normal donors (20.3% CD123+/MFI 1.6; Figure 1B). The observed CD123 expression levels were similar to those seen in primitive AML cells (72.4% CD123+/MFI 5.6; Figure 1B).

CD123 expression is significantly elevated in CD34+/CD38– cells of CP-CML and BC-CML patients compared with normal donors. The percentage of CD123+ cells within CD34+ (A) and CD34+/CD38– (B) subpopulations from normal donors (N), CP-CML, BC-CML, and AML patients has been determined by multicolor flow cytometry. **P < .01; ***P < .001 (by Mann-Whitney test compared with normal donors). (C) The percentage of CD123+ cells within CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– subpopulations of matched chronic and blast phase patient samples is plotted. (D) IL-3 levels in normal donor and in CP-CML patient plasma, with matched samples taken at diagnosis and following TKI treatment (on average 6 months on either imatinib or nilotinib), were measured by bead array.

CD123 expression is significantly elevated in CD34+/CD38– cells of CP-CML and BC-CML patients compared with normal donors. The percentage of CD123+ cells within CD34+ (A) and CD34+/CD38– (B) subpopulations from normal donors (N), CP-CML, BC-CML, and AML patients has been determined by multicolor flow cytometry. **P < .01; ***P < .001 (by Mann-Whitney test compared with normal donors). (C) The percentage of CD123+ cells within CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– subpopulations of matched chronic and blast phase patient samples is plotted. (D) IL-3 levels in normal donor and in CP-CML patient plasma, with matched samples taken at diagnosis and following TKI treatment (on average 6 months on either imatinib or nilotinib), were measured by bead array.

Interestingly, CD123 expression was consistently higher in BC-CML than CP-CML samples, confirmed by an increase in CD123 expression with disease progression in matched samples (Figure 1C). High CD123 expression was not only noted in myeloid BC CD34+/CD38– cells, but also in 3 of 3 lymphoid (94.1% ± 1.4% CD123+/MFI 20.9 ± 15.2) and 1 of 2 biphenotypic (74.7% CD123+/MFI 2.6 and 25.2% CD123+/MFI 2.2, respectively) BC-CML cases.

In addition, IL-3 plasma levels in CP-CML patients tended to be higher at diagnosis (4.3 ± 1.2 pg/mL) relative to plasma samples of healthy donors (1.1 ± 0.6 pg/mL) but were reduced in matched samples of TKI-treated patients (2.0 ± 0.5 pg/mL; Figure 1D).

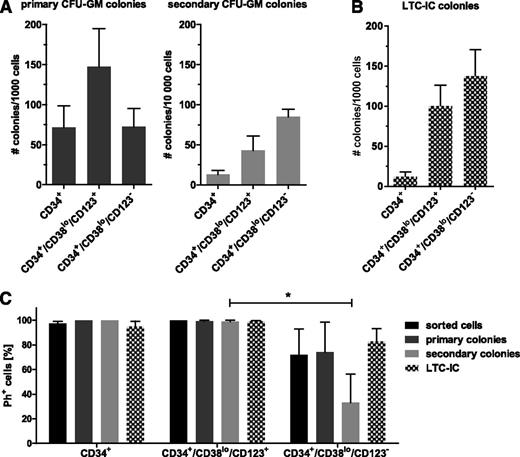

CD34+/CD38lo/CD123+ CP-CML LSPCs show in vitro self-renewal capacity

We compared the colony replating and LTC-IC potential, assays for primitive progenitors that can maintain long-term culture and can be used as surrogate markers of self-renewal capacity, of FACS-sorted CD123+ and CD123– CD34+/CD38lo subpopulations (supplemental Figure 2). Although the CD123+ CD34+/CD38lo subset formed more primary colonies (147.5 vs 72.4 per 1000 cells seeded, P = .06), these cells gave rise to fewer secondary colonies upon replating (42.9 vs 84.9 per 10 000 cells seeded, P = .1) compared with CD123– CD34+/CD38lo cells (Figure 2A). Similarly, LTC-IC colony numbers derived from CD123+ primitive CP-CML cells were lower than those from CD123– counterparts (100.3 vs 137.4 per 1000 cells seeded, P = .06; Figure 2B). However, BCR-ABL1 FISH revealed the presence of normal (Ph–) primitive cells specifically within the CD123– CD34+/CD38lo fraction and CFU and LTC-IC colonies (Figure 2C).

CD123+ and CD123– CD34+/CD38lo CP-CML cells show self-renewal capacity. FACS-sorted subpopulations of CP-CML early progenitor and stem cells were tested for their colony-forming and replating ability in methylcellulose media (A) as well as their long-term culture initiating potential (B). Graphs in both panels show an average of 5 individual patient samples. (C) The percentage of Ph+ cells within FACS-sorted populations and of plucked primary and secondary CFU and LTC-IC colonies was determined by BCR-ABL1 FISH (n = 3, *P < .05 by unpaired Student t test).

CD123+ and CD123– CD34+/CD38lo CP-CML cells show self-renewal capacity. FACS-sorted subpopulations of CP-CML early progenitor and stem cells were tested for their colony-forming and replating ability in methylcellulose media (A) as well as their long-term culture initiating potential (B). Graphs in both panels show an average of 5 individual patient samples. (C) The percentage of Ph+ cells within FACS-sorted populations and of plucked primary and secondary CFU and LTC-IC colonies was determined by BCR-ABL1 FISH (n = 3, *P < .05 by unpaired Student t test).

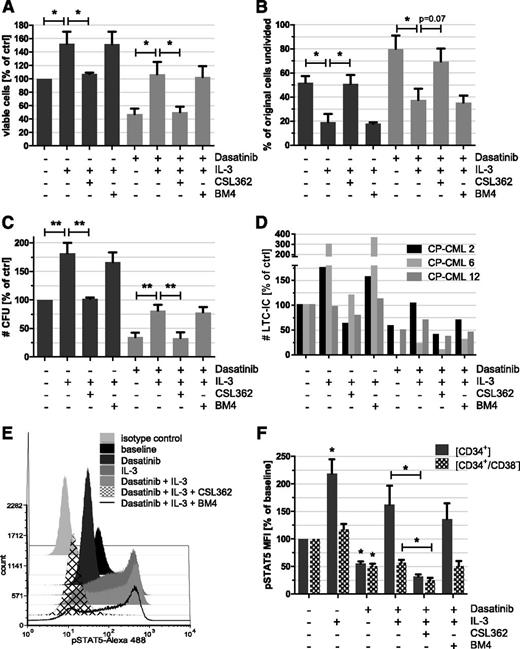

CSL362 prevents IL-3–mediated rescue of dasatinib-treated CP-CML LSPCs

Initial titration experiments ascertained optimal concentrations of IL-3 (1 ng/mL) required to rescue dasatinib-induced cell death and of CSL362 (10 µg/mL) needed to neutralize IL-3–mediated survival and signaling (supplemental Figure 3). As anticipated, IL-3 potently enhanced the survival of control dimethylsulfoxide-treated (152.2% vs 100%, P = .03) and dasatinib-exposed (106.5% vs 47.1%, P = .02) CP-CML CD34+ cells (Figure 3A) and induced proliferation, thereby reducing the percentage of undivided cells (Figure 3B). Accordingly, the numbers of CFUs (81.2% vs 34.5%, P = .004) and LTC-ICs (64.8% vs 35.8%, P = .4) were increased in IL-3 and dasatinib cotreated samples compared with dasatinib alone (Figure 3C-D). Importantly, CSL362, but not the matched isotype control antibody BM4, completely abrogated IL-3–mediated effects (Figure 3A-D), including the rescue of dasatinib-treated CP-CML CFUs (33.1% vs 81.2%, P = .005) and LTC-ICs (28.8% vs 64.8% on average, P = .3). Both CFU and LTC-IC colonies were predominantly Ph+ (93.8%, n = 4 and 95.5%, n = 2, respectively). In the absence of exogenous IL-3, CSL362 did not affect CML CFUs or LTC-ICs (data not shown).

IL-3 protects CP-CML LSPCs from the cytocidal effect of dasatinib, which is overcome by CSL362. CP-CML CD34+ cells were cultured with IL-3 (1 ng/mL), dasatinib (10 nM), and/or CSL362 or BM4 isotype-matched control antibody (both 1 µg/mL), as indicated, for 3 days. Cell viability was assessed using AnnexinV/7-Aminoactinomycin D flow cytometry assays (A) n = 7, whereas effects on cell proliferation were determined in CFSE-labeled CP-CML CD34+ cells; (B) n = 4, using flow cytometry, where the percentage of undivided cells was estimated using the proliferation tool in FCS Express. (C) CFU (n = 7) and (D) LTC-IC (n = 3) potential were monitored in parallel assays. (E) Combination of CSL362 and dasatinib effectively blocks STAT5 phosphorylation in IL-3–stimulated CP-CML progenitors. CD34+ cells of CP-CML patients were pretreated for 20 minutes with dasatinib (100 nM) and/or CSL362 or BM4 control antibody, respectively (both 10 µg/mL), prior to IL-3 (20 ng/mL) stimulation for 10 minutes (as indicated). Fixed and permeabilized cells were subsequently stained with conjugated antibodies against pY694-STAT5, CD34, and CD38 and analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) Quantitation of pSTAT5 flow cytometry data for CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– subpopulations as described in panel E from 3 independent experiments is shown. *P < .05; **P < .01 (by unpaired Student t test).

IL-3 protects CP-CML LSPCs from the cytocidal effect of dasatinib, which is overcome by CSL362. CP-CML CD34+ cells were cultured with IL-3 (1 ng/mL), dasatinib (10 nM), and/or CSL362 or BM4 isotype-matched control antibody (both 1 µg/mL), as indicated, for 3 days. Cell viability was assessed using AnnexinV/7-Aminoactinomycin D flow cytometry assays (A) n = 7, whereas effects on cell proliferation were determined in CFSE-labeled CP-CML CD34+ cells; (B) n = 4, using flow cytometry, where the percentage of undivided cells was estimated using the proliferation tool in FCS Express. (C) CFU (n = 7) and (D) LTC-IC (n = 3) potential were monitored in parallel assays. (E) Combination of CSL362 and dasatinib effectively blocks STAT5 phosphorylation in IL-3–stimulated CP-CML progenitors. CD34+ cells of CP-CML patients were pretreated for 20 minutes with dasatinib (100 nM) and/or CSL362 or BM4 control antibody, respectively (both 10 µg/mL), prior to IL-3 (20 ng/mL) stimulation for 10 minutes (as indicated). Fixed and permeabilized cells were subsequently stained with conjugated antibodies against pY694-STAT5, CD34, and CD38 and analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) Quantitation of pSTAT5 flow cytometry data for CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– subpopulations as described in panel E from 3 independent experiments is shown. *P < .05; **P < .01 (by unpaired Student t test).

There are several similarities in Bcr-Abl and IL-3 signaling with STAT5 activation being a point of convergence.29 STAT5 phospho–flow cytometry revealed that the observed effects of IL-3 and CSL362 on CP-CML LSPC survival were mirrored by STAT5 phosphorylation levels in CP-CML CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– cells (Figure 3E-F). Importantly, additive effects of combined dasatinib and CSL362 treatment, superseding the impact of dasatinib alone, in reducing STAT5 phosphorylation were seen in IL-3–stimulated cells (32.0% vs 162.6%, P = .02 for CD34+ cells and 24.7% vs 57.7%, P = .01 for CD34+/CD38– cells).

The combination of CSL362 even with low doses of dasatinib was able to neutralize IL-3 rescue in CP-CML CD34+ progenitors, evident from reduced numbers of viable CD34+ cells and CFUs (60.7% vs 81.3% of control at 0.1 nM dasatinib, P = .03; supplemental Figure 4). In the presence of multiple growth factors (5GF), likely to be present in the BM microenvironment,30 CSL362 treatment did not affect dasatinib-induced cell death at any dose (supplemental Figure 4).

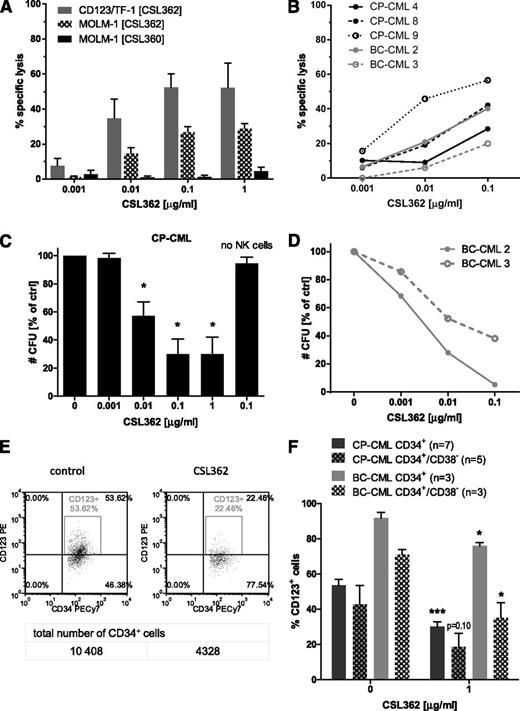

CSL362 mediates specific NK cell–dependent lysis of CD123+ CML LSPCs

First, CSL362-mediated ADCC was assessed in 4-hour LDH release assays using NK cells from healthy donors as effectors and CD123/TF-1 and MOLM-1 cells with high exogenous and endogenous CD123 expression, respectively, as target cells. CSL362 mediated dose-dependent cell lysis (52.4% and 26.9% lysis at 0.1 µg/mL CSL362 for CD123/TF-1 and MOLM-1, respectively), whereas CSL360, a human-mouse chimeric variant of 7G3 devoid of an ADCC-enhancing modification,24 did not (1.3% MOLM-1 cell lysis; Figure 4A). Importantly, progenitors from both CP- and BC-CML patients were killed by CSL362-mediated ADCC (37.5% lysis on average with 0.1 µg/mL CSL362; Figure 4B). This corresponded to a reduction in CFUs to 30.0% on average in CP-CML CD34+ cells (Figure 4C) and to 5.3% and 29.1%, respectively, in 2 BC-CML patient samples tested (Figure 4D). Also, CFUs of FACS-sorted CD34+/CD38+ and CD34+/CD38lo cells of a representative CP-CML patient were decreased to a similar extent when subjected to CSL362-mediated ADCC (supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that both subsets may be equally targeted. Accordingly, flow cytometry analysis revealed specific depletion of CD123-expressing CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– cells from CP-CML and BC-CML patients as a result of CSL362-mediated ADCC (Figure 4E-F).

CSL362 mediates specific, dose-dependent NK cell–induced cell lysis of CD123-positive leukemia cell lines and of CD34+ CML patient cells. (A) CD123-overexpressing TF-1 erythroleukemia cells (CD123/TF-1) and MOLM-1, a BC-CML cell line, were incubated for 4 hours with healthy donor NK cells at an E:T of 10:1 in the presence of increasing concentrations (as indicated) of CSL362 or CSL360 (negative control because it lacks ADCC activity). The percentage of antibody-dependent target cell lysis measured in at least 3 independent LDH assays is shown. (B) Percent lysis of individual CP- and BC-CML patients’ CD34+ cells during CSL362-induced ADCC was determined as described for panel A, and the number of remaining committed CP-CML (C) and BC-CML (D) progenitors was assessed by CFU assay. (E-F) CSL362-mediated ADCC selectively depletes CD123-expressing CML CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– cells. CD34+ cells of CP- and BC-CML patients subjected to CSL362-mediated ADCC as in panel A were analyzed by flow cytometry using antibodies against CD34, CD38, and CD123 (binding to a distinct epitope to CSL362). (E) Representative density and dot plots of CP-CML CD34+ cells are shown. (F) Quantitative analysis of the respective CD123-expressing populations. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (indicate significant differences by unpaired Student t test between control and CSL362-treated conditions).

CSL362 mediates specific, dose-dependent NK cell–induced cell lysis of CD123-positive leukemia cell lines and of CD34+ CML patient cells. (A) CD123-overexpressing TF-1 erythroleukemia cells (CD123/TF-1) and MOLM-1, a BC-CML cell line, were incubated for 4 hours with healthy donor NK cells at an E:T of 10:1 in the presence of increasing concentrations (as indicated) of CSL362 or CSL360 (negative control because it lacks ADCC activity). The percentage of antibody-dependent target cell lysis measured in at least 3 independent LDH assays is shown. (B) Percent lysis of individual CP- and BC-CML patients’ CD34+ cells during CSL362-induced ADCC was determined as described for panel A, and the number of remaining committed CP-CML (C) and BC-CML (D) progenitors was assessed by CFU assay. (E-F) CSL362-mediated ADCC selectively depletes CD123-expressing CML CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– cells. CD34+ cells of CP- and BC-CML patients subjected to CSL362-mediated ADCC as in panel A were analyzed by flow cytometry using antibodies against CD34, CD38, and CD123 (binding to a distinct epitope to CSL362). (E) Representative density and dot plots of CP-CML CD34+ cells are shown. (F) Quantitative analysis of the respective CD123-expressing populations. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (indicate significant differences by unpaired Student t test between control and CSL362-treated conditions).

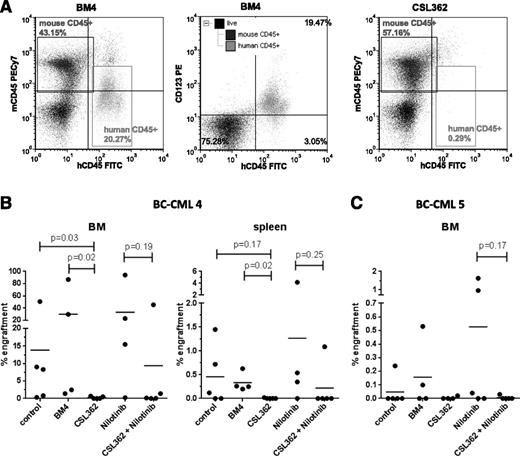

To assess the effect of CSL362 on leukemia-initiating cells, BC-CML patient cells were injected into sub-lethally irradiated, immune-compromised NOD/SCID mice. Indeed, CSL362 ex vivo pretreatment in the presence of NK cells reduced the leukemic cell engraftment of 2 individual BC-CML patient samples (Figure 5). Despite variable levels of engraftment between the patient samples, both FISH (100% of human engrafted cells were Ph+ for BC-CML 4) and BCR-ABL1 quantitative polymerase chain reaction (96.0 ±3.9% for BC-CML 4 and 104.1 ± 6.4% international scale for BC-CML 5) ascertained the leukemic nature of the engrafted cells independent of treatment. Moreover, flow cytometry studies showed that most of the engrafted hCD45+ cells were CD123+ (Figure 5A).

CSL362-mediated ADCC targets BC-CML leukemia-initiating cells. MNCs from patient BC-CML 4 (A-B) and BC-CML 5 (C) were incubated with 1 µg/mL CSL362 or BM4 isotype control antibody, without or with 1 µM nilotinib, in the presence of purified NK cells (E:T 1:1) overnight prior to intravenous transplantation into sub-lethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice. Human engraftment was analyzed by flow cytometry 12 weeks postinjection. (A) Representative flow plots for positive BM engraftment 12 weeks postinjection in a mouse from the BM4 group and for eliminated engraftment in a mouse from the CSL362 group are shown. The middle panel documents CD123 expression in engrafted cells. (B-C) Percentages of engraftment in BM and spleen of individual mice and the group means are plotted. Mice injected with BC-CML 5 cells did not show significant engraftment in the spleen. P values were determined by Mann-Whitney test.

CSL362-mediated ADCC targets BC-CML leukemia-initiating cells. MNCs from patient BC-CML 4 (A-B) and BC-CML 5 (C) were incubated with 1 µg/mL CSL362 or BM4 isotype control antibody, without or with 1 µM nilotinib, in the presence of purified NK cells (E:T 1:1) overnight prior to intravenous transplantation into sub-lethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice. Human engraftment was analyzed by flow cytometry 12 weeks postinjection. (A) Representative flow plots for positive BM engraftment 12 weeks postinjection in a mouse from the BM4 group and for eliminated engraftment in a mouse from the CSL362 group are shown. The middle panel documents CD123 expression in engrafted cells. (B-C) Percentages of engraftment in BM and spleen of individual mice and the group means are plotted. Mice injected with BC-CML 5 cells did not show significant engraftment in the spleen. P values were determined by Mann-Whitney test.

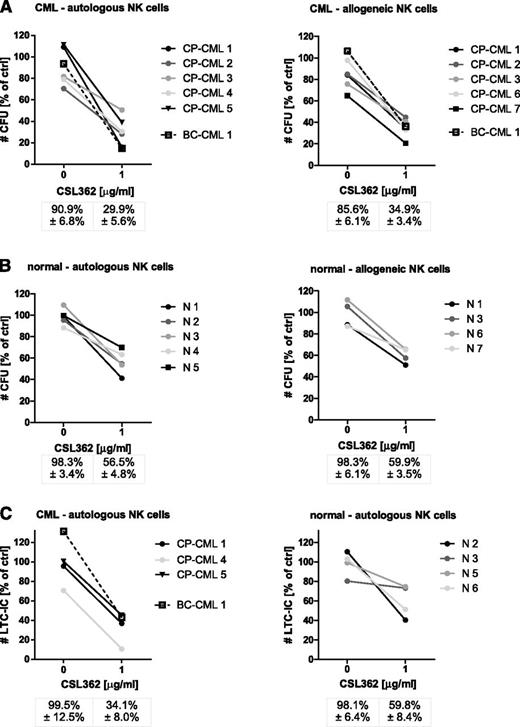

Autologous NK cells are potent effectors of CSL362-mediated ADCC in CP-CML LSPCs

Next, the efficiency of autologous NK cells of CML patients (Table 1), who achieved at least a CCyR, in mounting a CSL362-mediated ADCC response against matching cryopreserved CD34+ cells, collected at diagnosis, was tested. Remarkably, autologous CML patient NK cells induced CSL362-mediated cytotoxicity to the same extent as allogeneic healthy donor NK cells because the numbers of remaining CFUs were equivalent (28.0% vs 34.9%; Figure 6A) and CD123+ CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– populations were similarly depleted (supplemental Figure 6). Of note, autologous NK cells from dasatinib-treated patients appeared to be at least equally, if not more, potent compared with those of imatinib-treated patients (15.5% CFUs remaining, n = 2 vs 36.4% CFUs remaining, n = 3).

Clinical characteristics of patients included in the autologous NK cell study

| Patient . | Dx age in y (gender) . | Treatment (duration) . | Response at time of NK cell isolation* . | NK cells (% of lymphs) . | CD123 expression . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % CD123+ (MFI) [CD34+] . | % CD123+ (MFI) [CD34+/CD38–] . | |||||

| CP-CML 1 | 48 (M) | Dasatinib (12 mo) | CMR | 6.1 | 56.2 (2.6) | 10.7 (1.7) |

| CP-CML 2 | 70 (M) | Imatinib (28 mo) | MMR | 7.9 | 67.2 (2.9) | 15.1 (2.0) |

| CP-CML 3 | 64 (M) | Imatinib (10 mo) | CCyR | 6.8 | 48.7 (2.1) | 52.7 (2.1) |

| CP-CML 4 | 42 (M) | Imatinib (26 mo) | CCyR | 14.4 | 69.3 (2.5) | n. d. |

| CP-CML 5 | 64 (F) | Nilotinib (6 mo) | MMR | 5.1 | 70.1 (3.3) | 43.8 (2.6) |

| BC-CML 1 | 55 (F) | Dasatinib (48 mo) | CMR | 4.1 | 89.9 (6.7) | 84.3 (5.6) |

| Patient . | Dx age in y (gender) . | Treatment (duration) . | Response at time of NK cell isolation* . | NK cells (% of lymphs) . | CD123 expression . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % CD123+ (MFI) [CD34+] . | % CD123+ (MFI) [CD34+/CD38–] . | |||||

| CP-CML 1 | 48 (M) | Dasatinib (12 mo) | CMR | 6.1 | 56.2 (2.6) | 10.7 (1.7) |

| CP-CML 2 | 70 (M) | Imatinib (28 mo) | MMR | 7.9 | 67.2 (2.9) | 15.1 (2.0) |

| CP-CML 3 | 64 (M) | Imatinib (10 mo) | CCyR | 6.8 | 48.7 (2.1) | 52.7 (2.1) |

| CP-CML 4 | 42 (M) | Imatinib (26 mo) | CCyR | 14.4 | 69.3 (2.5) | n. d. |

| CP-CML 5 | 64 (F) | Nilotinib (6 mo) | MMR | 5.1 | 70.1 (3.3) | 43.8 (2.6) |

| BC-CML 1 | 55 (F) | Dasatinib (48 mo) | CMR | 4.1 | 89.9 (6.7) | 84.3 (5.6) |

CCyR, complete cytogenetic response; Dx, diagnosis; F, female; lymphs, lymphocytes; M, male; n. d., not determined.

CCyR (no Ph+ metaphases); CMR (undetectable BCR-ABL messenger RNA); MMR (≥3 log reduction of BCR-ABL messenger RNA).

Autologous CML patient NK cells trigger CSL362-mediated ADCC against matching CD34+ cells. (A) CD34+ of CML patients, collected at the time of diagnosis, were incubated for 4 hours with NK cells, isolated from the same patients after achieving complete cytogenetic response (see Table 1), at an E:T of 10:1 in the absence and presence of CSL362, and remaining CFUs were enumerated (left panel). In parallel, CML CD34+ cells were subjected to healthy donor NK cell–induced CSL362-mediated ADCC (right panel). (B) Normal CD34+ cells were used as targets of CSL362-mediated ADCC conferred by either autologous or allogeneic NK cells. (C) The long-term culture-initiating potential of normal and CML LSPCs subjected to CSL362-dependent autologous NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity is evaluated. All data are normalized to target cells alone.

Autologous CML patient NK cells trigger CSL362-mediated ADCC against matching CD34+ cells. (A) CD34+ of CML patients, collected at the time of diagnosis, were incubated for 4 hours with NK cells, isolated from the same patients after achieving complete cytogenetic response (see Table 1), at an E:T of 10:1 in the absence and presence of CSL362, and remaining CFUs were enumerated (left panel). In parallel, CML CD34+ cells were subjected to healthy donor NK cell–induced CSL362-mediated ADCC (right panel). (B) Normal CD34+ cells were used as targets of CSL362-mediated ADCC conferred by either autologous or allogeneic NK cells. (C) The long-term culture-initiating potential of normal and CML LSPCs subjected to CSL362-dependent autologous NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity is evaluated. All data are normalized to target cells alone.

To determine the effect of CSL362-mediated ADCC on normal progenitor and stem cells, matched healthy donor NK and CD34+ cells were used. Both autologous and allogeneic NK cells conferred CSL362-mediated ADCC (Figure 6B), but more importantly, the number of remaining normal CFUs was higher than that of CML CFUs (56.5% vs 28%, P = .008). Moreover, normal LTC-ICs were also less affected than CML LTC-ICs (59.8% vs 30.3%, P = .072; Figure 6C). In addition, although CML CFUs were predominantly Ph+ with or without CSL362-mediated ADCC (83.4% vs 89.4%, n = 4), the LTC-IC colonies remaining after CSL362-mediated ADCC of 2 of the 3 CP-CML patients were predominantly Ph– (Table 2), indicating that the majority of the spared LTC-ICs were of normal origin. Thus, the actual effect on Ph+ LTC-ICs in comparison with normal LTC-ICs (Figure 6C, right panel) was significantly greater (10.7% vs 59.8% remaining, P = .005).

Depletion of Ph+ LTC-IC colonies by CSL362-mediated ADCC

| Patient . | 0 µg/mL CSL362 . | 1 µg/mL CSL362 . | Ph+ LTC-IC colonies depleted . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTC-IC colony number (% Ph+) . | Calculated Ph+ LTC-IC colony number . | LTC-IC colony number (% Ph+) . | Calculated Ph+ LTC-IC colony number . | ||

| CP-CML 1 | 163 (67%) | 109 | 26 (36%) | 9 | 100 (91.7%) |

| CP-CML 4 | 312 (99%) | 312 | 48 (100%) | 48 | 264 (84.6%) |

| CP-CML 5 | 74 (63%) | 47 | 34 (9%) | 4 | 43 (91.5%) |

| Patient . | 0 µg/mL CSL362 . | 1 µg/mL CSL362 . | Ph+ LTC-IC colonies depleted . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTC-IC colony number (% Ph+) . | Calculated Ph+ LTC-IC colony number . | LTC-IC colony number (% Ph+) . | Calculated Ph+ LTC-IC colony number . | ||

| CP-CML 1 | 163 (67%) | 109 | 26 (36%) | 9 | 100 (91.7%) |

| CP-CML 4 | 312 (99%) | 312 | 48 (100%) | 48 | 264 (84.6%) |

| CP-CML 5 | 74 (63%) | 47 | 34 (9%) | 4 | 43 (91.5%) |

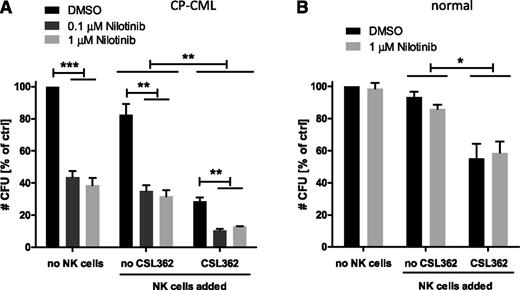

Additive effect of TKI-dependent and NK cell–dependent CSL362-mediated killing of CML LSPCs

To examine whether CSL362-mediated ADCC was effective in TKI-treated CML CD34+ cells and to determine if a combination treatment might improve selectivity for CML over normal progenitors, we first compared the effect of dasatinib and nilotinib at equipotent doses on CSL362-dependent cytotoxicity against MOLM-1 and CD34+ CP-CML cells. Interestingly, dasatinib (100 nM), but not nilotinib (1 µM), inhibited in vitro NK cell function (supplemental Figure 7), prompting the use of nilotinib in the following experiments.

To mimic the potential clinical setting of sequential TKI/CSL362 therapy, CP-CML CD34+ cells were pretreated with nilotinib for 48 hours and consecutively subjected to CSL362-mediated ADCC at an E:T ratio of 1:1 overnight in the presence of nilotinib. Importantly, this combination resulted in a significantly greater reduction in CFUs (to 12.7% remaining, P < .05) compared with either CSL362-mediated ADCC (28.7%) or nilotinib (38.6%) alone (Figure 7A). This additive effect was not observed when the same experiment was performed with normal CD34+ cells (with ADCC alone 55.2%, with nilotinib alone 85.9%, and in the combination of both 58.6% CFUs remaining; Figure 7B).

Combination of CSL362-mediated ADCC and TKI treatment further reduces CML but not normal CFUs. CP-CML (A) and normal CD34+ (B) (n = 3 each) cells were cultured with nilotinib at varying concentrations as indicated for 48 hours before overnight exposure to CSL362 (1 µg/mL) with or without allogeneic NK cells (E:T 1:1). Mean ± standard error of CFU colony numbers is shown. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (by unpaired Student t test).

Combination of CSL362-mediated ADCC and TKI treatment further reduces CML but not normal CFUs. CP-CML (A) and normal CD34+ (B) (n = 3 each) cells were cultured with nilotinib at varying concentrations as indicated for 48 hours before overnight exposure to CSL362 (1 µg/mL) with or without allogeneic NK cells (E:T 1:1). Mean ± standard error of CFU colony numbers is shown. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (by unpaired Student t test).

This was further substantiated by murine studies that demonstrated that although overnight ex vivo culture of BC-CML cells with 1 µM nilotinib alone did not reduce leukemic engraftment in NOD/SCID mice, a combination of nilotinib and CSL362-mediated ADCC was effective (Figure 5B-C).

Discussion

Although first- and second-generation TKIs revolutionized the CML treatment, elimination of the disease seems elusive for the majority of patients to date likely because of residual CML LSCs.6,7,10 Although CD123 is a recognized specific marker for AML CD34+/CD38– stem cells18,19 and has been suggested as a CML LSPC marker,31 its role in CML has not been elucidated in detail. In this study, we demonstrate that CD123 expression is significantly higher in CD34+/CD38– cells from both CP- and BC-CML patients as well as in CD34+ BC-CML cells compared with normal donors. Interestingly, CD123 expression in LSPCs increased with progression from chronic to blast phase CML, in line with previous reports associating the IL-3RA gene32 and an expansion of CD34+/CD38+CD123+CD45RA+ granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs)33 with BC-CML. As targeting AML LSCs with the specific CD123 mAbs 7G323 and CSL36224,34 has shown efficacy in vitro and in vivo, we further investigated the potential of CSL362 to deplete CML LSPCs. We show that CSL362 efficiently induces NK cell–dependent lysis of CD123-expressing CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– CP- and BC-CML cells and also neutralizes IL-3 function in CP-CML LSPCs.

In BC-CML, CD123+ GMPs, thought to constitute the leukemic, self-renewing stem cell population,33 represent the vast majority of CD34+ cells and were shown to be competent in maintaining leukemic CD123+ populations in engrafted immunocompromised mice,35 resembling the situation in AML.18 Our BC-CML engraftment studies in NOD/SCID mice also confirmed this notion. In the CP-CML setting, our studies comparing CD123+ and CD123– CD34+/CD38lo subsets yielded the unexpected result that the CD123– subpopulation showed higher replating and LTC-IC potential than the CD123+ subset. However, the enrichment of normal primitive cells in the CD123– subpopulation could be responsible for the higher replating and LTC-IC frequency because Bcr-Abl+ stem cells display reduced self-renewal ability compared with normal stem cells,36 suggesting a similar in vitro self-renewal capacity of leukemic CD123+ and CD123– CP-CML subsets. Clearly, murine studies evaluating the engraftment and serial transplantation ability of those cellular subsets are warranted to fully elucidate that question.

Apoptosis, proliferation, CFU, and LTC-IC assays confirmed the ability of CSL362 to prevent IL-3–mediated protection against dasatinib-induced cell death in CML LSPCs. However, this effect was lost in the presence of other cytokines, including GM-CSF and G-CSF, consistent with the implication of other cytokines in TKI resistance.12,13 Nevertheless, our experiments validated the potential of targeting CD123+ CML LSPCs with an anti-CD123 mAb.

CSL362 acts via a second, potentially more clinically relevant, mechanism by selectively inducing NK cell–dependent killing of CD123-expressing CML LSPCs. This is demonstrated by increased target cell lysis, reduction of CFUs and LTC-ICs, selective depletion of CD123+ CD34+ and CD34+/CD38– subpopulations, and reduction of leukemic engraftment in mice. As NK cell function may be reduced in CML,37 we questioned if CML patients’ NK cells were able to mount an effective CSL362-mediated ADCC response. Using NK cells from CML patients, who achieved at least CCyR, we could show that CSL362-induced ADCC is feasible in the autologous setting.

Of note, dasatinib, in contrast to nilotinib, inhibited NK cell function in ADCC assays, most likely because of inhibition of Src family kinases as reported previously.38,39 In vivo dasatinib treatment, in contrast, might cause positive immune-modulatory effects, such as enhanced NK cell activity40 and clonal expansion of large granular lymphocytes.41,42 Accordingly, NK cells isolated from 2 dasatinib-treated patients did not show any deficit in conferring CSL362-mediated ADCC.

An important consideration regarding the safety of CSL362 administration is the degree of selectivity for leukemic vs normal stem cells. Although we clearly demonstrated increased expression levels of CD123 in CML CD34+/CD38– cells, it was also evident that normal BM-derived progenitor and stem cells express CD123, albeit at lower levels. Preclinical toxicity studies of CSL362 in cynomolgus monkeys demonstrated the safety of this antibody in vivo, where no obvious effects on hematopoiesis were observed.43 Our own studies comparing the effects of CSL362-mediated ADCC indicated a preferential elimination of leukemic as opposed to normal CFUs and LTC-IC, but normal progenitor and stem cells are not completely spared. However, combination of TKI- and CSL362-dependent ADCC-induced cytotoxicity further increased selective targeting of CML over normal progenitors.

At which disease stage would it be most sensible to introduce CSL362 treatment? The majority of CML patients require long-term TKI therapy,10 associated with multiple concerns, such as development of resistance and tolerability issues. CSL362 treatment could be used to consolidate the TKI-induced molecular response in CP-CML patients and thus increase the chances of maintaining CMR off TKI therapy. Moreover, CD123+ GMPs, expanded in BC-CML and imatinib-resistant CML patients,33 represent excellent CSL362 targets. The reduction in murine engraftment of BC-CML cells by CSL362-mediated ADCC alone or in combination with nilotinib further substantiates this point. Potentially, the combination of TKI therapy and CSL362 may more effectively eliminate these progenitors in vivo than TKI treatment alone. However, NK cell competency during active disease stages remains to be ascertained. Of note, elevated CD123 expression was detected in CD34+ cells of patients not only in myeloid but also in lymphoid BC, consistent with high CD123 levels in B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), including Ph+ ALL.44,45

Another strategy targeting CD123, diphtheria toxin–conjugated IL-3, is currently under investigation for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome, AML, CML, and Ph+ ALL.44,46 However, although CD123 is an ideal target, the balance between specificity and potential toxicity may be delicate.47 Janus kinase 2 inhibition has also been suggested to overcome cytokine-mediated resistance of CML progenitors,12-14 but it may discriminate poorly between normal and leukemic progenitors.14 mAbs have proved successful in clinical practice, exemplified by the CD20-specific antibody rituximab to treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma48 and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.49

Taken together, we have established that CD123 expression is elevated in CML CD34+/CD38– cells and evaluated a novel anti-CD123 mAb-based approach to further complement current CML treatment to specifically target LSPCs by selective ADCC-mediated lysis and blocking IL-3–mediated signaling. Importantly, CSL362-mediated ADCC displayed selectivity for leukemic over normal progenitor and stem cells, which was further enhanced in CSL362/TKI combination treatments. Thus, targeting CD123 on LSPCs with CSL362 represents a potential new approach for CML therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Verity Saunders and Amity Frede for excellent technical assistance with patient sample processing and isolation of CD34+ CML cells and Richard D’Andrea for providing access to primary AML samples. We are grateful to Ian Lewis for help with the initial LTC-IC assay setup, Sarah Moore for sharing expertise in FISH on CFUs, and Craig Wallington-Beddoe for support with the murine studies.

This work was supported by research funding from CSL Limited (E.N., D.L.W., H.S.R., A.F.L., T.P.H., and D.K.H.) and by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and Cancer Australia. H.S.R. is supported by the Peter Nelson Leukaemia Research fund.

Authorship

Contribution: E.N. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; D.K.H. designed the research, reviewed the data, and wrote the manuscript; T.P.H. and D.L.W. were significantly involved in experimental design, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation; H.S.R., A.S.M.Y., and A.F.L. contributed to experimental design and reviewed the manuscript; H.S.R. also performed murine studies; M.B. determined IL-3 plasma levels; and S.J.B. and G.V. contributed to experimental design, provided reagents, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.N., H.S.R., A.F.L., and D.K.H. receive research funding from CSL Limited. D.L.W. and T.P.H. obtain funding from Novartis Oncology, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ariad, and CSL Limited. M.B., S.J.B., and G.V. are employed by CSL Limited. A.S.M.Y. receives research funding from Novartis Oncology.

Correspondence: Timothy Hughes, Department of Haematology, SA Pathology (RAH campus), PO Box 14, Rundle Mall, SA 5000, Australia; e-mail: timothy.hughes@health.sa.gov.au.