In this issue of Blood, Shanmuganathan et al have presented a model that has redefined the frequency of molecular (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] for BCR-ABL) testing in patients discontinuing tyrosine kinase therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) as part of attempts at treatment-free remission (TFR). This is a less conservative, more feasible approach that should make safe discontinuation a reality for more patients.1

Over the past 2 decades, the management of CML has evolved tremendously from therapies restricted to some individuals (bone marrow transplantation or α-interferon) with overall median time to disease progression for all patients of 4 to 5 years, to therapy now available to almost everyone, with a survival that approximates age-matched controls.2 Following imatinib, the first-generation drug, as second and third generation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been developed and come into usage, the survival of patients has not improved, but more patients are achieving faster deep molecular remission, which is the jumping off point for attempts at TFR.3 So why then, if the survival of chronic phase CML patients is so good on therapy, do patients and physicians want to consider the possibility of discontinuing therapy, or as it is known, TFR?

Patients with any disease like to be cured. With CML over the years, this definition has transformed from improved survival, to normal lifespan on therapy, to normal lifespan off therapy. No one wants to be taking medications they do not need, and it is well known that the longer a drug is taken, the poorer the compliance.4 The question arose as to whether we can safely discontinue CML therapy in some patients. This was elegantly looked at by the group in France and proven to be effective in roughly half of the patients who were deemed eligible for this study5 and confirmed by others for both first- and second-generation drugs.6

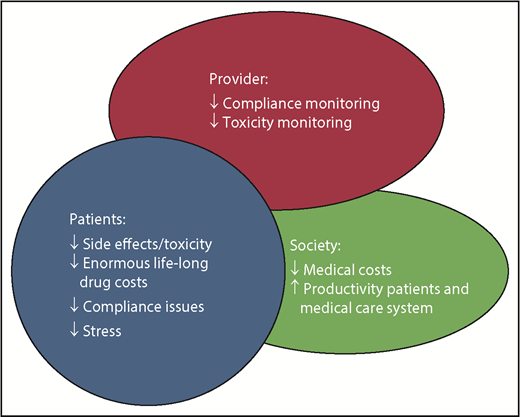

The advantages to TFR are obvious and multiple (see figure). However, stopping therapy on study vs in the real world is very different. So long as appropriate guidelines are followed, it can be done safely, and here is where the potential for problems takes place. With easy access to the Internet, patients are jumping on to this concept, in many cases without a good understanding of what is required for eligibility and safe follow-up.7 I dare say from my own observations that some treating physicians who are not CML specialists in some cases are not aware of or paying attention to the guidelines that have been laid out for safe discontinuation. These have been laid out in detail by several experts8 and by groups such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network9 and European LeukemiaNet (2019 Recommendations, R. Hehlmann et al, manuscript in preparation).

We do not have good-quality data on monitoring in TFR in the real world. We do have reports of what monitoring was like to follow therapy response, and it showed that a very large percentage of patients were not getting the recommended testing.10,11 True, in reality, the majority of newly diagnosed CML patients started front line on a TKI will do well even if they never have a single monitoring test done. The ones who fail to respond or lose response, because of resistance and/or intolerance leading to issues of compliance, are the patients who run the risk of disease progression to a stage more difficult or impossible to treat, or who may miss the opportunity to switch to a different drug or form of therapy that will change their outcomes.

Because of this concern, it is necessary to monitor all patients on therapy. Thus, it is even more important when discontinuing therapy electively, to catch the roughly half of patients who will lose their disease control, and get them back on therapy. Resuming therapy immediately on discovering a loss of response will result in virtually all patients recovering their disease control and deep molecular response.5,6

The question of what is appropriate monitoring in patients undertaking treatment discontinuation has been an issue, addressed well in Shanmuganathan and Hughes.8 For monitoring of patients on therapy, the usual guideline was a PCR test every 3 months at least until a stable major molecular remission was reached. On treatment discontinuation, this frequency was increased to monthly for at least the first year, bimonthly in the second year, and then every 3 months thereafter. This was based on the fact that virtually all but in very rare cases, molecular relapse would occur within the first 6 to 8 months.5,6 It has been argued that this is a very conservative, almost obsessive approach, that is inconvenient to patients and physicians, costly, and difficult to do in places where this frequency of testing is not available because of quality of testing or reimbursement. This may have discouraged physicians from approaching their patients to consider this or perhaps even having patients discontinue with suboptimal testing being done, or having patients refuse to consider it because of inconvenience.

The Adelaide, Australia group who have led the way in monitoring technology and recommendations8 have appropriately looked at this in a well-designed model, presented in this issue of Blood.1 Their conclusions suggest that less frequent monitoring is possible under certain conditions, making TFR more accessible and cost-effective, while retaining the safety net. What is important is that the criteria for consideration of therapy discontinuation are appropriate for a given patient, that good understanding by patient and physician and communication between patient and physician exist, and that the understanding that therapy reinitiation may be the end point of the exercise. It is hoped this “relaxed” approach will aid in getting the appropriate reimbursement in place to allow physicians to offer this to patients and for physicians to feel more comfortable and less restricted in that offering.

Even if only a minority of patients can successfully stop their TKI therapy, this would be a major cost savings. Although the introduction of quality generic TKIs has helped in some jurisdictions to some extent to reduce cost, the prevalence of CML patients on therapy continues to rise and hence also the costs. Stopping therapy will save money as suggested in initial studies.5

What is needed now is a good economic analysis of TFR in the real world, to prove this to those who control the purse strings.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author receives research funding and is a consultant with Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Takeda.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal