Key Points

Disruption of antioxidant selenoprotein synthesis exhibited significant defects in B lymphocyte development and HSC function.

Cell context and lineage dictate sensitivity to selenoprotein synthesis defects, with lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis serving as drivers.

Visual Abstract

The maintenance of cellular redox balance is crucial for cell survival and homeostasis and is disrupted with aging. Selenoproteins, comprising essential antioxidant enzymes, raise intriguing questions about their involvement in hematopoietic aging and potential reversibility. Motivated by our observation of messenger RNA downregulation of key antioxidant selenoproteins in aged human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and previous findings of increased lipid peroxidation in aged hematopoiesis, we used selenocysteine transfer RNA (tRNASec) gene (Trsp) knockout (KO) mouse model to simulate disrupted selenoprotein synthesis. This revealed insights into the protective roles of selenoproteins in preserving HSC stemness and B-lineage maturation, despite negligible effects on myeloid cells. Notably, Trsp KO exhibited B lymphocytopenia and reduced HSCs’ self-renewal capacity, recapitulating certain aspects of aged phenotypes, along with the upregulation of aging-related genes in both HSCs and pre-B cells. Although Trsp KO activated an antioxidant response transcription factor NRF2, we delineated a lineage-dependent phenotype driven by lipid peroxidation, which was exacerbated with aging yet ameliorated by ferroptosis inhibitors such as vitamin E. Interestingly, the myeloid genes were ectopically expressed in pre-B cells of Trsp KO mice, and KO pro-B/pre-B cells displayed differentiation potential toward functional CD11b+ fraction in the transplant model, suggesting that disrupted selenoprotein synthesis induces the potential of B-to-myeloid switch. Given the similarities between the KO model and aged wild-type mice, including ferroptosis vulnerability, impaired HSC self-renewal and B-lineage maturation, and characteristic lineage switch, our findings underscore the critical role of selenoprotein-mediated redox regulation in maintaining balanced hematopoiesis and suggest the preventive potential of selenoproteins against aging-related alterations.

Introduction

Age-related alterations in hematopoiesis manifest as a notable shift toward myeloid cell production, commonly referred to as myeloid skewing, alongside diminished levels of lymphoid cells, anemia, and reduced regenerative capacity of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).1 Several factors contribute to this decline,1,2 including increased CDC42 activity in aged HSCs, which is linked to the loss of cellular polarity,3 and reduced mitochondrial function coupled with epigenetic reprogramming.1 A growing body of evidence underscores age-related alterations in HSCs, particularly concerning their levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Functional analyses in mice have revealed an increase in the population of HSCs with high ROS levels (ROShigh), alongside a decrease in those with low ROS levels (ROSlow), compared with their younger counterparts, in which ROShigh HSCs exhibit a regenerative disadvantage compared with ROSlow HSCs.4 Indeed, transplantation of ROShigh HSCs into recipients resulted in lymphopenia and myeloid skewing, recapitulating the aging phenotypes observed in hematopoiesis.1,4 Although these findings show the critical involvement of ROS in the aging process of HSCs, the precise mechanisms and extent of ROS regulation in hematopoietic aging remain to be fully elucidated.

ROS are chemically reactive molecules, mainly generated as byproducts of the electron transport chain responsible for mitochondrial respiration.5,6 These ROS encompass various types, including superoxide anion (O2•–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•), all of which are rapidly metabolized and can modify and disrupt the function of DNA, proteins, and lipids. Notably, ROS can induce the accumulation of secondary products such as lipid peroxides, consequently triggering ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of programmed cell death.7 Excessive ROS levels can deteriorate oxidative stress, a condition implicated in cellular senescence and age-related diseases, including atherosclerosis, diabetes, and cancer.5,6,8,9 Therefore, maintaining a delicate balance between oxidants and antioxidants within cells is imperative for avoiding aging phenotype.

Selenoproteins represent a vital group of antioxidant enzymes, encompassing 25 selenocysteine (Sec)–containing proteins in humans and 24 in mice.10,11 Selenium, an essential trace element, in the Sec of selenoproteins is crucial for antioxidant activity.10,11 Sec is encoded by the UGA triplet at the messenger RNA (mRNA) level, which also serves as a stop codon.10,11 During translation, Sec is integrated into proteins by a Sec transfer RNA (tRNA; tRNASec), encoded by the n-TUtca2 gene, known as Trsp, only when the 3' untranslated region has a specific stem-loop structure.10,11 Examples of selenoproteins include thioredoxin reductase and glutathione peroxidase (GPX), which reduce the active form of thioredoxin and H2O2/lipid peroxides, respectively. Within the GPX family, GPX4 emerges as a key regulator of ferroptosis by mitigating lipid peroxides.12-14

Lipid peroxide accumulation in aging human HSCs is well documented,15 but the role of selenoprotein-regulated ferroptosis in aging phenotype and its reversibility remain unclear. Motivated by recent reports15,16 and our observations of impaired selenoprotein synthesis pathways in aged HSCs, we hypothesized that selenoproteins play a crucial role in maintaining hematopoiesis as part of an antioxidant system that counters age-related alterations. By using Trsp knockout (KO) mice as a model to simulate disrupted selenoprotein synthesis, we demonstrated that selenoproteins protect HSCs’ stemness and facilitate B lymphocyte maturation. This disruption triggered aging-related gene upregulation and a lineage-dependent shift driven by lipid peroxidation, which worsened with age but was mitigated by ferroptosis inhibitors. Notably, both Trsp KO and aged wild-type pro-B/pre-B cells also showed a unique potential for myeloid lineage switching. These findings highlight the crucial role of selenoproteins in regulating redox balance and suggest their potential involvement in sustaining hematopoiesis during aging.

Methods

Animals

All animals were housed at the Foundation for Biomedical Research and Innovation (Kobe, Japan) using a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle, at ambient temperature of 21.5°C ± 1°C and 30% to 70% humidity. All animal procedures were followed by the Guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Foundation for Biomedical Research and Innovation (21-11, 24-08). The Mx1-Cre and R26-CreERT2 strains were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Trsp floxed mouse strain (RBRC02681) was provided by Riken BioResource Research through the National BioResource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology-Japan/Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, Japan. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Japan SLC,Inc.

All additional methods are provided in supplemental Methods available on the Blood website.

Results

Lineage- and age-dependent effects of Trsp KO hematopoiesis

Accumulation of ROS stands out as a hallmark of aged hematopoiesis.1 We observed downregulation of mRNA for key antioxidant selenoproteins in aged human HSCs compared with their younger counterparts (supplemental Figure 1A-B),17 consistent with previous findings reporting decreased GPX activity and increased lipid peroxidation in peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells from older individuals.15,16 We further demonstrated that aging-related DNA damage, induced by treating human cord blood CD34+ cells with etoposide,3,18-24 resulted in reduced GPX1/2 and GPX4 protein expression and increased lipid peroxides, measured using C11-BODIPY 581/591 (supplemental Figure 1C-D). These results motivated us to examine previously unrecognized roles of selenoproteins in maintaining youthful hematopoiesis. To test this idea, we used a mouse model enabling time-dependent deletion of the tRNASec gene using Cre-loxP system in Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice (Figure 1A-B).25,26 Six weeks after polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pI-pC) treatment, Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice exhibited the expected DNA recombination (supplemental Figure 2A) and nearly undetectable tRNASec levels across both mature and immature bone marrow (BM) fractions (supplemental Figure 2B). As anticipated, Trsp KO mice displayed decreased levels of selenoprotein, such as SEPHS2, GPX1/2, and GPX4, both in the BM and spleen (Figure 1C). This finding was corroborated by mass spectrometry analysis of Trsp KO mouse BM cells (supplemental Figure 2C). Staining for 4-hydroxynonenal (HNEJ-1) revealed an accumulation of advanced lipid peroxidation end products across lineages (supplemental Figure 2D-E). Phenotypic analysis unveiled that Trsp KO mice developed macrocytic anemia (supplemental Figure 2F-G), with erythrocyte degradation and the presence of erythrocytes with nuclear remnants in the PB (supplemental Figure 2G), as well as B lymphocytopenia and splenomegaly filled with erythroblasts and expansion of red pulp (supplemental Figure 2H-I; Figure 1D), consistent with prior reports.26 Although the phenotypic changes of heterozygous KO were subtle (supplemental Figure 2J-K), the erythroid and B-lineage findings observed in homozygous KO mice were replicated by Trspfl/fl: R26-CreERT2 mice upon tamoxifen treatment (supplemental Figure 3A-E), reinforcing the direct impact of Trsp KO on the hematopoietic system.

Lineage- and age-dependent effects of Trsp KO hematopoiesis. (A) Schematic representation of the pathways involved in Sec incorporation into selenoproteins. This process involves a multiprotein complex that includes tRNA Sec 1 associated protein 1 (TRNAU1AP), eukaryotic elongation factor (EEFSEC), and tRNASec isoform by SECIS binding protein 2 (SECISBP2). SECISBP2 interacts with the SECIS stem-loop element located in the 3′ untranslated region of mammalian selenoprotein mRNAs, enabling the decoding UGA Sec codons at the ribosomal acceptor site to mediate Sec incorporation into nascent polypeptide. (B) Utilization of a mouse model allowing time-dependent deletion of the tRNAsec gene (Trsp) through the Cre-loxP system in Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice. Trsp gene is flanked by loxP sequences, shown by arrowheads. Trsp excision was induced by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of pI-pC every other day for 3 times. Control mice were pI-pC–treated Trspfl/fl mice, whereas Trsp KO mice represent Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice. (C) Western blot analysis for SEPHS2, GPX1/2, and GPX4 in whole BM cells and spleen cells derived from control mice and Trsp KO mice. Filled triangles indicate target protein bands, whereas open triangles represent nonspecific bands. (D) Absolute number and frequency of CD71+Ter-119+, CD3+, B220+, CD11b+Gr-1+, and CD11b+Gr-1– cells in the BM are shown. Frequencies of CD71+Ter-119+, CD3+, B220+, CD11b+Gr-1+, CD11b+Gr-1– cells, PB, and spleen of each group are shown (n = 5 per group). (E) Frequency of B220+ and CD11b+Gr-1+ cells in the BM of each group (young represents age <20 weeks; aged, 81 weeks; n = 5 per each group). (F) Representative histograms and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in B220+ or CD11b+ BM cells of aged control and Trsp KO mice (n = 5 per group; age 81 weeks). (G) Schematic representation of noncompetitive BM transplantation assays. (H) Counts of white blood cells (WBCs) in whole blood from recipient mice at 3 months after transplantation (control group, n = 6 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). (I) Frequency of CD45.2+ in the PB and of B220+ and CD11b+Gr-1+ cells in CD45.2+ cells of recipient mice at 3 months after transplantation (control group, n = 6 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant.

Lineage- and age-dependent effects of Trsp KO hematopoiesis. (A) Schematic representation of the pathways involved in Sec incorporation into selenoproteins. This process involves a multiprotein complex that includes tRNA Sec 1 associated protein 1 (TRNAU1AP), eukaryotic elongation factor (EEFSEC), and tRNASec isoform by SECIS binding protein 2 (SECISBP2). SECISBP2 interacts with the SECIS stem-loop element located in the 3′ untranslated region of mammalian selenoprotein mRNAs, enabling the decoding UGA Sec codons at the ribosomal acceptor site to mediate Sec incorporation into nascent polypeptide. (B) Utilization of a mouse model allowing time-dependent deletion of the tRNAsec gene (Trsp) through the Cre-loxP system in Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice. Trsp gene is flanked by loxP sequences, shown by arrowheads. Trsp excision was induced by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of pI-pC every other day for 3 times. Control mice were pI-pC–treated Trspfl/fl mice, whereas Trsp KO mice represent Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice. (C) Western blot analysis for SEPHS2, GPX1/2, and GPX4 in whole BM cells and spleen cells derived from control mice and Trsp KO mice. Filled triangles indicate target protein bands, whereas open triangles represent nonspecific bands. (D) Absolute number and frequency of CD71+Ter-119+, CD3+, B220+, CD11b+Gr-1+, and CD11b+Gr-1– cells in the BM are shown. Frequencies of CD71+Ter-119+, CD3+, B220+, CD11b+Gr-1+, CD11b+Gr-1– cells, PB, and spleen of each group are shown (n = 5 per group). (E) Frequency of B220+ and CD11b+Gr-1+ cells in the BM of each group (young represents age <20 weeks; aged, 81 weeks; n = 5 per each group). (F) Representative histograms and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in B220+ or CD11b+ BM cells of aged control and Trsp KO mice (n = 5 per group; age 81 weeks). (G) Schematic representation of noncompetitive BM transplantation assays. (H) Counts of white blood cells (WBCs) in whole blood from recipient mice at 3 months after transplantation (control group, n = 6 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). (I) Frequency of CD45.2+ in the PB and of B220+ and CD11b+Gr-1+ cells in CD45.2+ cells of recipient mice at 3 months after transplantation (control group, n = 6 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant.

Given that lymphocytopenia and anemia are prominent features in age-related hematopoiesis, we sought to elucidate how aging interacts with Trsp KO to manifest these phenotypes. Intriguingly, we observed an accelerated decline in B-cell numbers, subsequently inducing relative myeloid skewing in aged Trsp KO mice (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 4A). We hypothesized that this phenotype could be attributed to the accumulation of ROS in Trsp KO B cells. To investigate this, we stained BM B cells with C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX to assess lipid peroxidation and cytoplasmic ROS, respectively. Although there was no discernible difference in ROS accumulation between B and myeloid cells of young control and KO mice (supplemental Figure 4B), aged KO mice exhibited increased accumulation of lipid peroxide and cytoplasmic ROS specifically in B lymphocytes (Figure 1F). On the contrary, myeloid cells showed only cytoplasmic ROS accumulation (Figure 1F).

To ascertain whether the observed phenotypes in Trsp KO mice occur in a cell-autonomous manner, we conducted BM transplantation experiments by transplanting CD45.2+ control Trspfl/fl and Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre donor cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice (Figure 1G). This approach allowed us to assess the hematopoietic reconstitution capacity of transplanted HSCs. Consistent with the findings in primary mice, 3 months after pI-pC treatment, the Trsp KO group exhibited B-cell reduction and anemia compared with the control group (Figure 1H-I; supplemental Figure 4C-D). Notably, despite the profound B-cell phenotypes, Trsp KO did not lead to BM failure or shortened survival (supplemental Figure 4E). These results underscored the lineage-specific effects of Trsp KO on hematopoiesis.

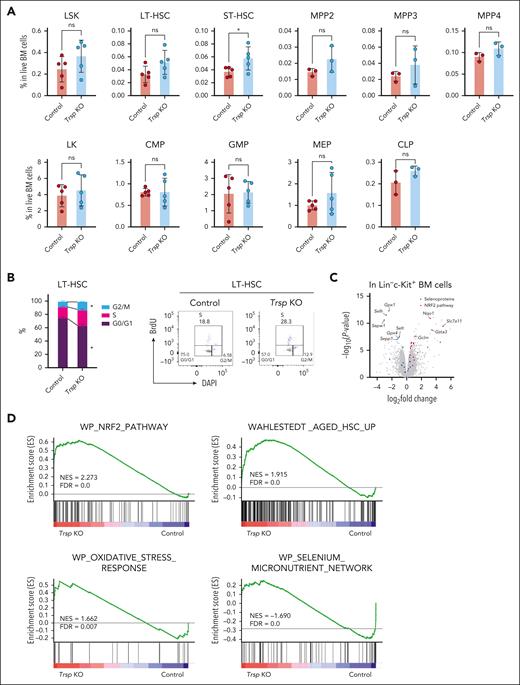

Trsp KO modulates HSCs’ state and elicits NRF2 activation across HSPCs

Given the perturbation of mature hematopoietic cells observed in Trsp KO, we aimed to investigate whether these effects originate from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). We first assessed various HSPC compartments in Trsp KO mice, including long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs), multipotent progenitors (MPPs; MPP2, MPP3, and MPP4), and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs). Interestingly, Trsp KO led to an increase in ST-HSCs without significant changes in LT-HSCs, MPPs, or progenitors (Figure 2A). Furthermore, cell cycle analysis revealed that Trsp KO resulted in a less quiescent state of LT-HSCs (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 5A), suggesting that enhanced cell cycle activity in LT-HSCs leads to an increase in ST-HSCs (Figure 2A).

Trsp KO modulates HSCs’ state and elicits NRF2 activation across HSPCs. (A) Frequency of LSK (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1+), LT-HSCs (CD48–CD150+ LSK), and ST-HSCs (CD48–CD150– LSK), megakaryocytic and erythroid-biased MPP2 (CD135–CD150+CD48+ LSK), myeloid-biased MPP3 (CD135–CD150–CD48+ LSK), lymphoid-biased MPP4 (CD135+ LSK), LK (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; CD34+FcγR– LK), granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs; CD34+FcγR+ LK), megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs; CD34–FcγR– LK), and CLPs (Lin–c-KitintSca1intCD127+CD135+) in the BM of each group (LSK, LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, LK, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs, n = 5 per group; MPP2, MPP3, MPP4, and CLP, n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles and percentages of bromodeoxyuridine-positive (BrdU+; S phase), DAPI+ (4N) BrdU– (G2/M phase), and DAPI+ (2N) BrdU– (G0/G1 phase) LT-HSCs in the BM (control group, n = 4 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 3 mice). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (C) Volcano plot illustrating differential mRNA expression in Trsp KO Lin–c-Kit+ cells, with selenoproteins highlighted in blue and NRF2 pathway genes highlighted in red. Control mice were pI-pC–treated Trspfl/fl mice, whereas Trsp KO mice represent Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice (n = 4 per group). (D) GSEA enrichment plot for upregulated and downregulated genes in RNA-seq of Trsp KO vs control in Lin–c-Kit+ cells (n = 4 per group). (E) Identification of distinct hematopoietic clusters in control and KO Lin–c-Kit+ cells base on uniform manifold approximation and projection analysis from scRNA-seq. The estimated fractions of stem, progenitor, and mature cells are labeled and highlighted (n = 1 per group). (F) Violin plots depicting mRNA expression of selenoptoteins (Gpx1, Selh, and Sepw1) in the indicated clusters (HSC, MPP2, MPP3, and MPP4). Box plot and kernel density plot of log2 expression values are shown. P values were reanalyzed using Loupe browser. In the box-and-whisker plots, the 0th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 100th percentiles and mean (dashed lines) are shown. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score; ns, not significant.

Trsp KO modulates HSCs’ state and elicits NRF2 activation across HSPCs. (A) Frequency of LSK (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1+), LT-HSCs (CD48–CD150+ LSK), and ST-HSCs (CD48–CD150– LSK), megakaryocytic and erythroid-biased MPP2 (CD135–CD150+CD48+ LSK), myeloid-biased MPP3 (CD135–CD150–CD48+ LSK), lymphoid-biased MPP4 (CD135+ LSK), LK (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; CD34+FcγR– LK), granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs; CD34+FcγR+ LK), megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs; CD34–FcγR– LK), and CLPs (Lin–c-KitintSca1intCD127+CD135+) in the BM of each group (LSK, LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, LK, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs, n = 5 per group; MPP2, MPP3, MPP4, and CLP, n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles and percentages of bromodeoxyuridine-positive (BrdU+; S phase), DAPI+ (4N) BrdU– (G2/M phase), and DAPI+ (2N) BrdU– (G0/G1 phase) LT-HSCs in the BM (control group, n = 4 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 3 mice). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (C) Volcano plot illustrating differential mRNA expression in Trsp KO Lin–c-Kit+ cells, with selenoproteins highlighted in blue and NRF2 pathway genes highlighted in red. Control mice were pI-pC–treated Trspfl/fl mice, whereas Trsp KO mice represent Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice (n = 4 per group). (D) GSEA enrichment plot for upregulated and downregulated genes in RNA-seq of Trsp KO vs control in Lin–c-Kit+ cells (n = 4 per group). (E) Identification of distinct hematopoietic clusters in control and KO Lin–c-Kit+ cells base on uniform manifold approximation and projection analysis from scRNA-seq. The estimated fractions of stem, progenitor, and mature cells are labeled and highlighted (n = 1 per group). (F) Violin plots depicting mRNA expression of selenoptoteins (Gpx1, Selh, and Sepw1) in the indicated clusters (HSC, MPP2, MPP3, and MPP4). Box plot and kernel density plot of log2 expression values are shown. P values were reanalyzed using Loupe browser. In the box-and-whisker plots, the 0th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 100th percentiles and mean (dashed lines) are shown. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score; ns, not significant.

To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying Trsp KO effects on HSPCs, we next performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-purified Lin–c-Kit+ BM cells from Trspfl/fl and Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice at 10 weeks after pI-pC injection in biological quadruplicates for each model. Transcriptomes of Lin–c-Kit+ cells exhibited substantial differences, as evident from principal component analysis (supplemental Figure 5B; Figure 2C). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) included a series of downregulated selenoproteins such as Gpx1, Gpx4, Selh, Selt, Sepw1, or Sepp1. This observation can be attributed to the phenomenon of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, in which UGA-coding Sec serves as a premature stop codon upon the absence of Trsp.27

In contrast, DEGs upregulated in Trsp KO encompassed pathways related to nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NRF2; Figure 2C), which are involved in ROS scavenging and detoxification.28 Notable examples included Scl7a11, Nqo1, Gclm, and Gsta3. Gene ontology and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of Trsp KO vs control RNA-seq results revealed positive enrichment not only for aged HSC characteristics29,30 but also for NRF2 pathway (Figure 2D), a finding consistent with observations in selenoprotein-deficient macrophages, liver, and BM cells.25,26 To further decipher how Trsp loss affects early lineage commitment of HSCs to MPPs, we conducted single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) targeting 10 000 BM Lin–c-Kit+ cells each from control and Trsp KO primary mice at 9 weeks after deletion. To ensure data quality, we excluded cells with elevated mitochondrial gene expression, because this is indicative of cell death.31,32 Uniform manifold approximation and projection analysis integrating both models revealed the expected stem and progenitor clusters, including LT-HSC, MPP, and erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid progenitors (Figure 2E).33-37 Selenoproteins exhibited uniform downregulation across all HSPC fractions, indicating consistent involvement of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway in modulating selenoprotein mRNA levels regardless of lineage variation (Figure 2F). Conversely, NRF2 target genes displayed upregulation across all Trsp KO HSPC fractions (supplemental Figure 5C). These findings suggest that in the absence of selenoproteins, NRF2 compensates for impaired ROS scavenging in HSPCs, and the behavior of NRF2 alone cannot entirely account for the lineage-specific phenotype observed in the Trsp KO model.

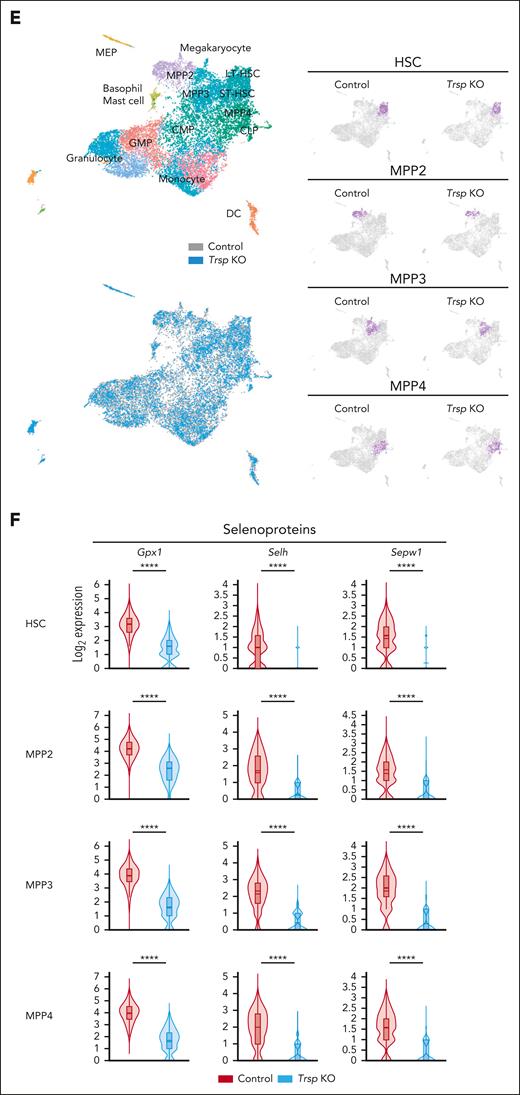

Selenoproteins are required for the maintenance of HSC function

Although detailed examination of primary Trsp KO mice revealed altered HSC states and lineage-specific effects, analyzing primary models alone cannot fully evaluate the intrinsic effects of Trsp-depleted HSCs compared with normal HSCs. To address this, we conducted an in vivo self-renewal assessment of control Trspfl/fl and Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre mice model in a competitive transplantation experiment. Equal numbers of CD45.2+ BM cells from each model were mixed with CD45.1+ wild-type BM cells and injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice. After DNA recombination induced by pI-pC injection, we monitored donor- and competitor-derived chimerism in PB monthly and euthanized all recipients 5 months later to assess chimerism in BM (Figure 3A). Although Trsp KO resulted in a significant disadvantage in PB chimerism, we observed relatively comparable chimerism in BM HSPCs 6 months after transplantation (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 5D). Notably, the competitive disadvantage in PB and BM was primarily attributed to the near-complete loss of Trsp KO cells in B220+ and CD3+ fractions (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 5D). To evaluate the long-term reconstitution ability, we also performed a serial transplant assay using whole BM cells from the first recipients. Remarkably, we observed a profound loss of donor-derived chimerism in all lineages of mature and HSPC fractions (Figure 3D), indicating that Trsp KO HSCs exhibited impaired long-term self-renewal and reconstitution ability compared with control HSCs. These results underscore the critical roles of selenoproteins in HSC maintenance in vivo. Given that transplant stress can raise ROS levels,38 we examined whether transplantation-induced ROS contributes to the impaired function of Trsp KO HSCs in a noncompetitive transplant experiment (supplemental Figure 5E). Although the control group accumulated ROS after transplant, the KO group did not, indicating that the impairments are not due to transplant-induced ROS (supplemental Figure 5F).

Selenoproteins are required for the maintenance of HSC function. (A) Schematic representation of competitive BM transplantation assays. (B) Percentage of donor-derived (CD45.2+) cells in total live cells in PB in primary and serial competitive transplantation (control group, n = 7 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). (C) Percentage of donor-derived (CD45.2+) cells in each indicated population in PB in primary and serial competitive transplantation (control group, n = 7 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). (D) The percentage of donor-derived cells in each indicated population in the BM after 4 months of serial competitive transplantation (control group, n = 4 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 7 mice). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Selenoproteins are required for the maintenance of HSC function. (A) Schematic representation of competitive BM transplantation assays. (B) Percentage of donor-derived (CD45.2+) cells in total live cells in PB in primary and serial competitive transplantation (control group, n = 7 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). (C) Percentage of donor-derived (CD45.2+) cells in each indicated population in PB in primary and serial competitive transplantation (control group, n = 7 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 8 mice). (D) The percentage of donor-derived cells in each indicated population in the BM after 4 months of serial competitive transplantation (control group, n = 4 mice; Trsp KO group, n = 7 mice). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

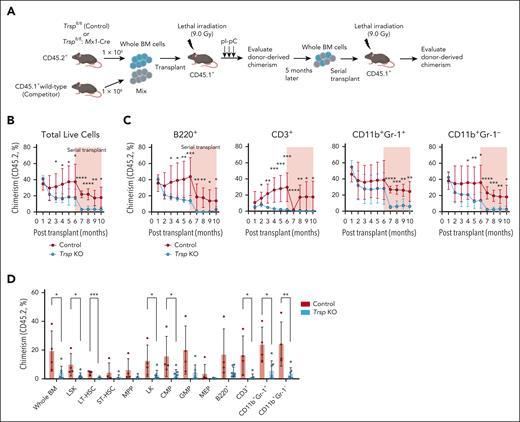

Trsp-deficient HSPCs are subject to ferroptosis

To examine the self-renewal and proliferation capacity of Trsp KO BM cells in vitro, we conducted a colony formation assay using whole BM cells from control and Trsp KO mice. Despite previous data indicating no decrease in the frequency of HSPCs in Trsp KO mice (Figure 2A), we observed that Trsp KO completely blocked colony formation capacity in cytokine-supplemented methylcellulose media, including myeloid, erythroid, and pre-B conditions (Figure 4A). To investigate the mechanism underlying cell death in Trsp KO BM cells, we targeted various regulatory factors of programmed cell death pathways in magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS)-sorted Lin– BM HSPCs (Figure 4B). Baseline viability of HSPCs from Trsp KO mice significantly decreased, accompanied by lipid peroxide accumulation during ex vivo culture (Figure 4C-E). Using the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) or α-tocopherol (α-Toc), a prominent component of vitamin E (Vit E), whose concentrations effectively rescued cell death caused by RSL3 (GPX4 inhibitor) in control Lin– cells, we observed significant rescue in KO Lin– cells with Fer-1 or α-Toc (Figure 4E; supplemental Figure 6A-B). Fer-1 also markedly inhibited lipid peroxide accumulation of Trsp KO HSPCs (Figure 4C). However, apoptosis (Z-VAD(OH)-FMK[zVAD]) or necroptosis (7-Cl-O-Nec1[Nec-1s]) inhibitors did not prevent cell death in KO HSPCs (Figure 4E; supplemental Figure 6A-B). Intriguingly, aged HSPCs exhibited modestly higher sensitivity to RSL3 than young HSPCs (supplemental Figure 6C). These findings suggest that ferroptosis is the key cell death pathway in KO HSPCs, further supported by the rescue of colony formation by Fer-1 and α-Toc (Figure 4F). These align with recent reports indicating that GPX4, one of the selenoproteins, serves as a main regulator of ferroptosis,12 and Gpx4 deficiency induced ferroptosis in HSPCs in vitro.39

Trsp-deficient HSPCs are subject to ferroptosis. (A) Representative pictures showing colony formation of whole BM cells in methylcellulose using M3434 for myeloid colonies. Colonies were scored 7 days after plating in methylcellulose in M3434, M3436, and M3630, for myeloid, erythroid, and pre-B colonies, respectively (n = 3 independent experiments). (B) Schematic representation of programmed cell death pathways. Ferroptosis (left) is triggered by iron-dependent accumulation of lethal ROS and lipid peroxides. Ferroptosis can be inhibited by iron (Fe2+) chelators such as deferoxamine (DFO). α-Toc and Fer-1 inhibit ferroptosis by suppressing lipid peroxidation. Apoptosis and necroptosis (right) are primarily regulated via TNFR1 signaling. Upon TNF binding, TNFR1 undergoes a conformational change, activating 2 potential cell death execution mechanisms. Caspase-8 triggers apoptosis by activating the classical caspase cascade and inactivating RIP1 and RIP3 through cleavage. As an alternative pathway, phosphorylated RIP1 and RIP3 initiate necroptosis independently of caspase-8. zVAD inhibits apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-8, whereas Necrostatin-1s (Nec-1s) inhibits necroptosis by inhibiting RIP1. (C) Relative MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining in Lin– cells from control mice and Trsp KO mice 24 hours after culturing in the presence of Fer-1 (1 μM; n = 5 independent experiments). (D) Frequency of DAPI– cells in Lin– cells measured 48 hours after treatment with Fer-1 (n = 5 independent experiments). (E) Heat map illustrating relative cell number of viable Lin– cells compared with day 0, as determined by the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability assay, 48 hours after culturing in the presence of Fer-1 (1-5 μM), α-Toc (1-2 mM), zVAD (25-50 μM), and Nec-1s (50-100 μM; n = 3 per group). (F) Colonies were scored 7 days after plating in methylcellulose (MethoCult M3434) in the presence of Fer-1 (5 μM) and α-Toc (2 mM; n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide GSH, glutathione-SH; ns, not significant; RIP1, receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR1, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1.

Trsp-deficient HSPCs are subject to ferroptosis. (A) Representative pictures showing colony formation of whole BM cells in methylcellulose using M3434 for myeloid colonies. Colonies were scored 7 days after plating in methylcellulose in M3434, M3436, and M3630, for myeloid, erythroid, and pre-B colonies, respectively (n = 3 independent experiments). (B) Schematic representation of programmed cell death pathways. Ferroptosis (left) is triggered by iron-dependent accumulation of lethal ROS and lipid peroxides. Ferroptosis can be inhibited by iron (Fe2+) chelators such as deferoxamine (DFO). α-Toc and Fer-1 inhibit ferroptosis by suppressing lipid peroxidation. Apoptosis and necroptosis (right) are primarily regulated via TNFR1 signaling. Upon TNF binding, TNFR1 undergoes a conformational change, activating 2 potential cell death execution mechanisms. Caspase-8 triggers apoptosis by activating the classical caspase cascade and inactivating RIP1 and RIP3 through cleavage. As an alternative pathway, phosphorylated RIP1 and RIP3 initiate necroptosis independently of caspase-8. zVAD inhibits apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-8, whereas Necrostatin-1s (Nec-1s) inhibits necroptosis by inhibiting RIP1. (C) Relative MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining in Lin– cells from control mice and Trsp KO mice 24 hours after culturing in the presence of Fer-1 (1 μM; n = 5 independent experiments). (D) Frequency of DAPI– cells in Lin– cells measured 48 hours after treatment with Fer-1 (n = 5 independent experiments). (E) Heat map illustrating relative cell number of viable Lin– cells compared with day 0, as determined by the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability assay, 48 hours after culturing in the presence of Fer-1 (1-5 μM), α-Toc (1-2 mM), zVAD (25-50 μM), and Nec-1s (50-100 μM; n = 3 per group). (F) Colonies were scored 7 days after plating in methylcellulose (MethoCult M3434) in the presence of Fer-1 (5 μM) and α-Toc (2 mM; n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide GSH, glutathione-SH; ns, not significant; RIP1, receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR1, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1.

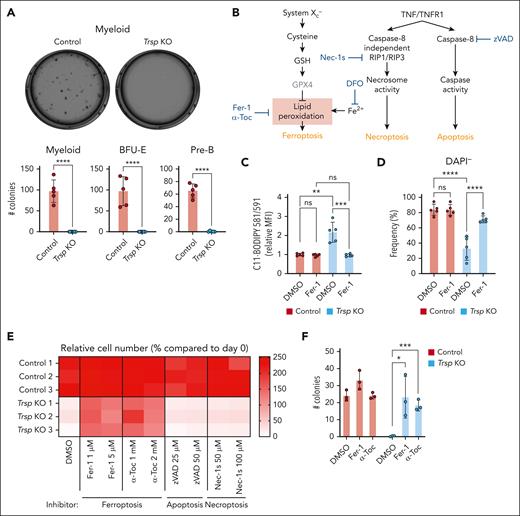

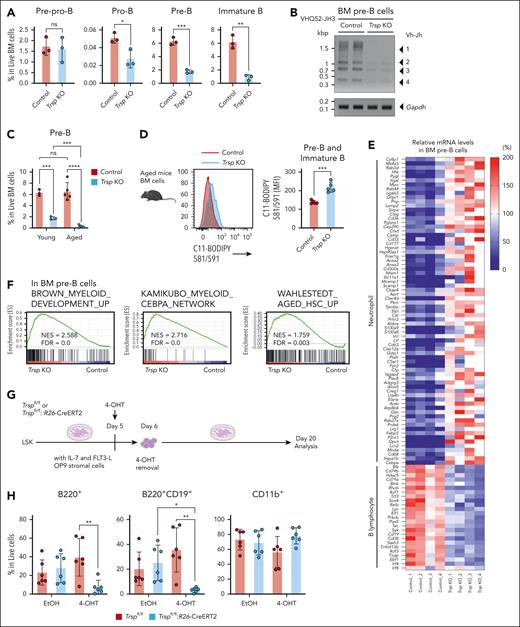

Dysregulation of redox control by Trsp KO disrupts B-cell differentiation and transcriptional program

Despite the observed B-cell reduction in Trsp KO mice, CLP frequencies remained comparable with controls (Figure 2A), and DEGs specific to MPP4 were not identified. Consequently, we aimed to pinpoint the stage of blocked B-cell maturation. B progenitors differentiate sequentially from pre–pro-B, pro-B, pre-B, and immature B cells.40 Notably, in Trsp KO mice, pre-B and immature B cells were significantly reduced, whereas pre–pro-B stages were comparable with that of control mice in BM and spleen (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 7A). Trsp KO pre-B cells exhibited impaired immunoglobulin heavy chain (Igh) V(D)J and immunoglobulin light chain (Igl) Vκ-Jκ gene rearrangement, indicating the functional impairment at the pre–B-cell stage (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 7B). However, CD19+ cells from Trsp KO spleens showed normal proliferation and IgM secretion upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/ interleukin-4 (IL-4) stimulation,41 suggesting functional integrity under stimulation (supplemental Figure 7C-E). Importantly, aged Trsp KO mice exhibited further pre–B-cell reduction and lipid peroxide accumulation (Figure 5C-D; supplemental Figure 7F-G), highlighting the detrimental impact of lipid peroxidation on B-cell differentiation. Similarly, aged wild-type mice accumulated lipid peroxides, particularly in the spleen (supplemental Figure 7H). These findings suggest overlapping lipid peroxidation–induced B-cell phenotypes in Trsp KO and aged mice.

Dysregulation of redox control by Trsp KO disrupts B-cell differentiation and transcriptional program. (A) Frequency of pre–pro-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19–CD43+), pro-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+CD43+), pre-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+CD43–), and immature B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM+CD19+CD43–) cells in the BM of control and Trsp KO mice (n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (B) Representative image of polymerase chain reaction amplification. pre-B cells were isolated from BM by cell sorting, and Igh V(D)J gene rearrangement was determined by polymerase chain reaction amplification with Gapdh as a loading control (n = 2 per group). (C) Frequency of pre-B cells in the BM of each group categorized by age (young [age <20 weeks], n = 3 mice per group; aged [81 weeks], n = 5 mice per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (D) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining in pre-B and immature B cells in the BM cells of aged control mice and aged Trsp KO mice (n = 5 mice per group; age 81 weeks). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (E) Heat map showing genes that regulate neutrophil and B-cell differentiation evaluated by RNA-seq in Trsp KO BM pre-B cells. The listed genes are from gene ontology biological process. Neutrophil includes neutrophil degranulation (GO:0043312) and Cebpa; B lymphocyte includes lymphocyte differentiation (GO:0030098), lymphocyte differentiation (GO: 0030098), regulation of B-cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050855), B-cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050853), regulation of B-cell proliferation (GO:0030888), and Ebf1, Irf4, and Irf8 (n = 4 per group). (F) GSEA enrichment plot for upregulate genes in RNA-seq of Trsp KO vs control in pre-B cells (n = 4 per group). (G) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. LSK cells were sorted from the BM of Trspfl/fl or Trspfl/fl: R26-CreERT2 mice, expanded until day 6, and cultured under B-cell differentiation conditions with OP-9 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 and FLT3-L. Cells were treated with 4-OHT for 24 hours on day 5. On day 20, they were analyzed by flow cytometry. (H) The frequency of B220+, B220+CD19+, and CD11b+ cells in each group is shown. P values were calculated by 1-way ANOVA test. (I) Schematic of BM transplantation assays. CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–CD19+IgM– (pro-B/pre-B) BM cells sorted from the BM of control (Trspfl/fl) or Trsp KO (Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre) mice at 8 weeks after pI-pC injection, with rescue cells (CD45.1+ whole BM cells) injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice. (J) Flow cytometric profiles for B220+ and CD11b+ in respective conditions and frequency of CD45.2+B220+ and CD45.2+CD11b+ cells in the BM of each group were assessed 1 month after transplantation (n = 5 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (K) The appearance of donor pro-B/pre-B–derived CD45.2+CD11b+ fractions in recipient PB is shown in each group (defined as >0.3% in live PB cells). P values were calculated using Fisher exact test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. EtOH, ethanol; FDR, false discovery rate; FLT3-L, FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; Igh V(D)J, immunoglobulin heavy chain V(D)J; IL-7, interleukin-7; NES, normalized enrichment score; ns, not significant.

Dysregulation of redox control by Trsp KO disrupts B-cell differentiation and transcriptional program. (A) Frequency of pre–pro-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19–CD43+), pro-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+CD43+), pre-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+CD43–), and immature B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM+CD19+CD43–) cells in the BM of control and Trsp KO mice (n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (B) Representative image of polymerase chain reaction amplification. pre-B cells were isolated from BM by cell sorting, and Igh V(D)J gene rearrangement was determined by polymerase chain reaction amplification with Gapdh as a loading control (n = 2 per group). (C) Frequency of pre-B cells in the BM of each group categorized by age (young [age <20 weeks], n = 3 mice per group; aged [81 weeks], n = 5 mice per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (D) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining in pre-B and immature B cells in the BM cells of aged control mice and aged Trsp KO mice (n = 5 mice per group; age 81 weeks). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (E) Heat map showing genes that regulate neutrophil and B-cell differentiation evaluated by RNA-seq in Trsp KO BM pre-B cells. The listed genes are from gene ontology biological process. Neutrophil includes neutrophil degranulation (GO:0043312) and Cebpa; B lymphocyte includes lymphocyte differentiation (GO:0030098), lymphocyte differentiation (GO: 0030098), regulation of B-cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050855), B-cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050853), regulation of B-cell proliferation (GO:0030888), and Ebf1, Irf4, and Irf8 (n = 4 per group). (F) GSEA enrichment plot for upregulate genes in RNA-seq of Trsp KO vs control in pre-B cells (n = 4 per group). (G) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. LSK cells were sorted from the BM of Trspfl/fl or Trspfl/fl: R26-CreERT2 mice, expanded until day 6, and cultured under B-cell differentiation conditions with OP-9 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 and FLT3-L. Cells were treated with 4-OHT for 24 hours on day 5. On day 20, they were analyzed by flow cytometry. (H) The frequency of B220+, B220+CD19+, and CD11b+ cells in each group is shown. P values were calculated by 1-way ANOVA test. (I) Schematic of BM transplantation assays. CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–CD19+IgM– (pro-B/pre-B) BM cells sorted from the BM of control (Trspfl/fl) or Trsp KO (Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre) mice at 8 weeks after pI-pC injection, with rescue cells (CD45.1+ whole BM cells) injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice. (J) Flow cytometric profiles for B220+ and CD11b+ in respective conditions and frequency of CD45.2+B220+ and CD45.2+CD11b+ cells in the BM of each group were assessed 1 month after transplantation (n = 5 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (K) The appearance of donor pro-B/pre-B–derived CD45.2+CD11b+ fractions in recipient PB is shown in each group (defined as >0.3% in live PB cells). P values were calculated using Fisher exact test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. EtOH, ethanol; FDR, false discovery rate; FLT3-L, FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; Igh V(D)J, immunoglobulin heavy chain V(D)J; IL-7, interleukin-7; NES, normalized enrichment score; ns, not significant.

To elucidate how Trsp KO dysregulates B-cell transcriptional program, we next performed RNA-seq analysis of FACS-purified BM pre–pro-B cells and pre-B cells from control and Trsp KO mice, with biological quadruplicates for each model. We observed a downregulation of pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and B-cell receptor signaling in the Trsp KO group, particularly pronounced in pre-B cells (Figure 5E; supplemental Figure 8A). For example, Igκ germ line transcription and Igκ rearrangement are regulated by the concerted action of multiple transcription factors (TFs) at the Eκ enhancers, including Tcf3, Pax5, and Irf4, whose downregulation was validated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (supplemental Figure 8B).40,42 In contrast, neutrophil-related genes were ectopically upregulated in Trsp KO group, especially in pre-B cells (Figure 5E; supplemental Figure 8A), which are supported by GSEA showing significant upregulation of myeloid TF CEBPA in pre-B cells (Figure 5F). However, scRNA-seq revealed no alterations in myeloid or lymphoid gene expression within the MPP4/CLP clusters (supplemental Figure 8C). GSEA also demonstrated a positive enrichment of aging HSC characteristics and the NRF2 pathway in pre-B cells (Figure 5F; supplemental Figure 8D).

Direct involvement of selenoproteins in B-lineage maturation in vitro and in vivo

To determine whether the impaired maturation of B lymphocytes is a direct consequence of Trsp KO, we performed an in vitro differentiation assay (Figure 5G-H; supplemental Figure 8E). BM LSK (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1+) cells from Trspfl/fl and Trspfl/fl: R26-CreERT2 mice were cultured on OP9 stromal cells with IL-7 and FLT3-L. On day 5, 4-OHT (4-hydroxytamoxifen) was added for 24 hours to delete the Trsp gene (supplemental Figure 8F). The cells were harvested on day 20 and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 5H; supplemental Figure 8E). Trsp KO LSK cells showed reduced B-lineage differentiation but not myeloid differentiation compared with controls (Figure 5H; supplemental Figure 8E), highlighting the critical role of selenoproteins in early B-cell development.

To investigate the differential potential of Trsp KO B progenitors in vivo, we performed transplantation of CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+ (pro-B and pre-B) cells from CD45.2+ control or Trsp KO model, along with CD45.1+ wild-type whole BM cells, into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients (Figure 5I). Subsequently, we analyzed the cellular composition of CD45.2+ cells in the BM of recipients. Our analysis revealed a significant decrease in CD45.2+ donor-derived cells in the Trsp KO group, indicating reduced viability of B progenitors from Trsp KO mice in vivo (Figure 5J; supplemental Figure 8G). Notably, Trsp KO pro-B/pre-B cells demonstrated a significant potential to generate CD11b+ myeloid cells in the recipient BM and PB (Figure 5J-K), consistent with the upregulation of myeloid-related genes observed in RNA-seq (Figure 5E-F; supplemental Figure 8A). These CD11b+ cells derived from Trsp KO pro-B/pre-B cells displayed morphology comparable with those from wild-type mice (supplemental Figure 8H). mRNA expression analysis of Trsp KO pro-B/pre-B–derived CD11b+ cells showed downregulation of genes involved in lymphocyte differentiation and B-cell receptor signaling pathways, alongside reciprocal upregulation of myeloid genes, to a level similar to that of wild-type CD11b+ cells (supplemental Figure 8I). A flow cytometry–based neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) assay further demonstrated that Trsp KO pro-B/pre-B–derived CD11b+ cells formed NETs, indicated by MPO+ histone H3+ staining,43 suggesting functional similarity to wild-type CD11b+cells (supplemental Figure 8J). These findings highlight the requirement of selenoproteins for B-cell maturation and highlight how their deficiency can disturb the normal differentiation program, leading to a B-to-myeloid lineage switch.

Next, we conducted a similar transplant with pro-B/pre-B cells of young or aged wild-type mice to assess the differentiation potential as observed in Trsp KO mice (supplemental Figure 9A). Our analysis revealed a significant reduction in CD45.2+B220+ cells in the aged group (supplemental Figure 9B-C), indicating impaired engraftment or proliferation of aged pro-B/pre-B progenitors. Interestingly, aged pro-B/pre-B cells showed the potential to generate CD11b+ myeloid cells in the recipient BM (supplemental Figure 9B), similar to Trsp KO B progenitors. The phenotypes of these uniquely generated CD11b+ cells, including morphology, gene expression, and NET formation, recapitulated those of Trsp KO–derived cells (supplemental Figure 9D-F). These findings highlight shared characteristics between physiological aging and Trsp KO in B progenitors, further underscoring the functional connection between the 2 conditions.

Ferroptosis modulation shapes B-cell phenotype in Trsp KO model

Given the rescue of Trsp KO HSPC survival by α-Toc (Figure 4E; supplemental Figure 6A), we postulated that dietary Vit E plays a critical role in protecting Trsp-depleted hematopoiesis from ferroptosis. To test this hypothesis, mice were fed with a fixed formulation diet containing either 75 mg/kg of Vit E (control diet) or an undetectable amount of Vit E (Vit E–deficient diet; Figure 6A). Remarkably, we observed an exacerbation of phenotypes in the B, erythroid, and myeloid lineages in the BM of Trsp KO mice fed with the Vit E–deficient diet for 6 weeks, whereas LSK and LK (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–) cells were largely unaffected (Figure 6B; supplemental Figure 10A-B). B lymphocytes and B progenitors in the BM exhibited additional accumulation of lipid peroxide and cytoplasmic ROS 3 weeks after the initiation of Vit E–deficient diet, suggesting a cooperative induction of ferroptosis in the B lineage due to deficiencies in both selenoproteins and Vit E (Figure 6C-D).

Ferroptosis modulation shapes B-cell phenotype in Trsp KO model. (A) Schematic representation of feeding a Vit E–deficient diet. (B) Frequency of B220+, CD11b+Gr-1+, and CD11b+Gr-1– cells in the BM of each group administered Vit E–deficient diet for 6 weeks (Trsp KO/Vit E–deficient diet group, n = 2 mice; other groups, n = 3 mice per group). (C) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in B220+ BM cells of each group administered Vit E–deficient diet for 3 weeks. For C11-BODIPY 581/591, control/control diet group included 4 mice; other groups, 5 mice per group. For CellROX, control/control diet group included 3 mice; other groups, 4 mice per group. Representative histograms of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in B220+ BM cells of each group are provided. (D) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in pre–pro-B, pro-B, pre-B, and immature B cells in BM cells of each group (control/control diet group, n = 3 mice; other groups, n = 4 mice per group). (E) Schematic representation of feeding a Vit E–rich diet. (F) Frequency of B220+ CD11b+Gr-1+ and CD11b+Gr-1– cells in the spleen of each group administered Vit E–rich diet for 6 weeks (n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, not significant.

Ferroptosis modulation shapes B-cell phenotype in Trsp KO model. (A) Schematic representation of feeding a Vit E–deficient diet. (B) Frequency of B220+, CD11b+Gr-1+, and CD11b+Gr-1– cells in the BM of each group administered Vit E–deficient diet for 6 weeks (Trsp KO/Vit E–deficient diet group, n = 2 mice; other groups, n = 3 mice per group). (C) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in B220+ BM cells of each group administered Vit E–deficient diet for 3 weeks. For C11-BODIPY 581/591, control/control diet group included 4 mice; other groups, 5 mice per group. For CellROX, control/control diet group included 3 mice; other groups, 4 mice per group. Representative histograms of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in B220+ BM cells of each group are provided. (D) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 and CellROX staining in pre–pro-B, pro-B, pre-B, and immature B cells in BM cells of each group (control/control diet group, n = 3 mice; other groups, n = 4 mice per group). (E) Schematic representation of feeding a Vit E–rich diet. (F) Frequency of B220+ CD11b+Gr-1+ and CD11b+Gr-1– cells in the spleen of each group administered Vit E–rich diet for 6 weeks (n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, not significant.

Next, we fed the mice with Vit E–rich diet (500 mg/kg) to clarify whether antiferroptotic effects of Vit E unlock the impaired B-cell differentiation of Trsp KO mice (Figure 6E). Indeed, Vit E–rich diet administered for 6 weeks partially rescued the frequency of B220+ B cells in Trsp KO mice (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 10C). These results indicate that ferroptosis occurring in the B cells of Trsp KO mice serves as the underlying cause of differentiation disorders. Notably, the 8-week administration of a Vit E–rich diet reduced the cell-cycling state of Trsp KO LT-HSCs shown in Figure 2B (supplemental Figure 10D-E), consistent with the rescue effect of Vit E (α-Toc) on HSPC ferroptotic cell death induced by RSL3 in vitro (supplemental Figure 6B). Together, these findings suggest that the phenotypes observed in Trsp KO mice are primarily attributable to ferroptosis, and dietary intervention can modulate the ferroptosis-induced phenotype both in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

Although the functions of selenoproteins in hematopoiesis have been documented in several contexts,26,44 the specific roles they play in HSC stemness and B lymphocyte maturation have remained elusive. Our study uncovers a protective role of selenoproteins in maintaining HSC stemness and highlights their critical involvement in B lymphocyte maturation (supplemental Figure 11A). Disruption of selenoprotein synthesis results in intrinsic impairment of B-lineage maturation, both in vivo and in vitro settings. Furthermore, B lymphocytes exhibit increased susceptibility to ferroptosis, particularly with aging. Although the Trsp KO model presents nonphysiological conditions that may amplify this phenotype, our data and others’15,16 suggest a link between physiological aging and selenoprotein-related traits in impaired HSC self-renewal (Figure 3B-D; supplemental Figure 5D) and B-lineage maturation (Figure 1D; Figure 5A), altered gene expression profiles (Figure 2D; Figure 5F; supplemental Figure 8D), and a unique potential for B-to-myeloid lineage switching (Figure 5J-K; supplemental Figure 9B-C). Because age-related declines in selenoprotein expression have been noted in various cell types, including human vascular smooth muscle cells and rat hepatocytes,45,46 further studies are expected to fairly evaluate the reduction in selenoproteins and the subsequent lipid peroxidation in aged human HSCs or HSCs from patients with age-related blood disorders.

Trsp KO mouse, serving as a model of selenoprotein synthesis failure, exhibited notable phenotypes in erythroid and B lymphocytes, whereas the myeloid lineage remained largely unaffected. The erythroid phenotypes align with previous findings,26,44 showing that selenoproteins modulate stress erythroid progenitors and the splenic microenvironment during stress-induced erythropoiesis.44 The erythroid phenotype in Trsp KO mice bears resemblance to that of the Gpx4 KO model, highlighting the importance of GPX4 in erythropoiesis.47,48 However, unlike Gpx4 KO mice, which showed no impairment in B-cell maturation in the BM,39,49 our experiments consistently demonstrated impaired B-cell maturation in Trsp KO model (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 7A). Notably, this B-cell phenotype was accompanied by lipid peroxide accumulation, exacerbated upon aging (Figure 1E-F; Figure 5C-D) or Vit E deficiency (Figure 6B-D). Although GPX4 is known to reduce lipid peroxides, other selenoproteins, such as thioredoxin reductase 1, likely contribute to protecting B cells by removing hydrogen peroxide via the peroxiredoxin/thioredoxin system, implicated in ferroptosis suppression.50 Myeloid cells did not accumulate lipid peroxides with age or Vit E deficiency, suggesting reliance on alternative antioxidant systems or inherent resistance to lipid peroxidation.

One of the most intriguing phenomena observed in Trsp KO mice is the lineage switch from pro-B/pre-B cells to myeloid cells, a trait also shared with aged wild-type pro-B/pre-B cells. As shown in supplemental Figure 8A, RNA-seq data from the Trsp KO pre–pro-B stage revealed modest changes in TFs involved in B and myeloid differentiation, with more pronounced alterations at the pre-B stage (Figure 5E). However, scRNA-seq did not reveal changes in the expression of myeloid or lymphoid lineage–specific genes within the MPP4/CLP clusters (supplemental Figure 8C), suggesting the switch occurs after the pre–pro-B stage (supplemental Figure 8A). Notably, CEBPA overexpression in B cells has been shown to drive reprogramming into myeloid cells.51 The significant upregulation of Cebpa in Trsp KO pro-B/pre-B cells may underlie this switch. Given the reported effects of oxidative stress on chromatin structure,52,53 future studies should investigate whether ROS or lipid peroxides influence lineage-determining TF expression and chromatin states.

Although Trsp KO HSPCs displayed cell death in vitro (Figure 4D-E), the survival of mice with hematopoietic cell–specific Trsp KO was not shortened (supplemental Figure 4E), suggesting protective mechanisms within the BM microenvironment. Factors such as the hypoxic and nutrient-rich environment, cellular density, and support from BM niche cells may contribute to this protection. In our experimental model, Vit E supplementation at least partially ameliorated the phenotype of Trsp KO HSPCs (Figure 4E; supplemental Figure 6A) and B cells (Figure 6F), highlighting the protective roles of Vit E within the BM, consistent with reports of Vit E supporting Gpx4 KO HSPC survival in vitro.39,48,54 Additionally, high cell density has been shown to increase resistance to ferroptosis induced by cysteine deprivation and GPX4 inhibition.55 Cell-cell contact through the NF2-Hippo-YAP pathway also confers ferroptosis resistance in epithelial cells.56 Considering the unique partnership between HSCs and mesenchymal stem cells in maintaining healthy hematopoiesis,57,58 it is plausible that mesenchymal stem cells help shield HSCs from ferroptosis.

The disruption in B lymphocyte differentiation in Trsp KO mice accelerated with aging. RNA-seq analysis revealed upregulation of NRF2 target genes in HSPCs (Figure 2C-D), B progenitors (supplemental Figure 8D), and myeloid cells of Trsp KO mice. It has been documented that, as aging progresses, NRF2 activation becomes less efficient due to a decline in the oxidative stress response.59 Additionally, positive regulators of NRF2 have been shown to decrease with aging in specific contexts.60-64 This reduction in compensatory mechanisms by NRF2 may explain the accelerated aging phenotype of Trsp KO mice. Furthermore, numerous cellular and structural changes occur in the BM microenvironment with aging,1,65 which may contribute to the loss of compensatory mechanisms and progression of phenotypes. Future studies aimed at elucidating these aging-related alterations, alongside defects in selenoprotein synthesis, that drive hematopoietic aging phenotypes are crucial for understanding the underlying mechanisms of aging-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Miyu Miyazaki for help with mass spectrometry. The supercomputing resource was provided by Human Genome Center (The University of Tokyo). Part of the illustration was created with BioRender.com.

This work was supported by The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP22J22398 [Y.A.], JP22KJ1980 [Y.A.], JP21K08432 [H.Y.], JP22H04922 [Advanced Animal Model Support; H.Y.], 16H06279 [Platform for Advanced Genome Science; H.Y.], JP23K07824 [K.N.], JP24H00866 [D.I.], JP20H00537 [D.I.], JP23H00430 [D.I.], and JP24K21298 [D.I.]), Japan Science and Technology Agency CREST (JPMJCR23B7 [D.I.] and JPMJCR19H4 [S.T.]), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP23ama221126 [D.I.] and JP24ama221135 [K.N.]), The Naito Foundation (H.Y. and K.N.), American Society of Hematology (D.I.), Japanese Society of Hematology (D.I.), Ono Medical Research Foundation (D.I.), Ono Pharmaceutical Foundation for Oncology (D.I.), The Mitsubishi Foundation (D.I.), The Cell Science Research Foundation (D.I.), Kobayashi Foundation for Cancer Research (D.I.), Takeda Science Foundation (K.N. and D.I.), Chugai Foundation for Innovative Drug Discovery Science (D.I.), Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research (D.I.), Friends of Leukemia Research Fund (K.N.), Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund (K.N.), Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (K.N.), MSD Life Science Foundation, Public Interest Incorporated Foundation (K.N.), and SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (D.I.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.A., H.Y., K.N., A.T.-K., and D.I. designed the study; T. Shigehiro and T.I. supervised polymerase chain reaction analysis of immunoglobulin heavy chain V(D)J and immunoglobulin light chain Vκ-Jκ gene rearrangements, B-cell differentiation experiments, and B progenitor transplantation experiments; Y.A., Y. Kong, and S.T. performed immunohistochemical staining; Y.A., Y.T., and K.I. performed label-free proteome analysis; Y.A., H.Y., Y.H., Y.M., and A. Toyoda performed single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq); Y.A., W.Z., and M.N. performed computational analyses of RNA-seq data; Y.A., H.Y., T. Suzuki, W.Z., H.I., Y. Koike, M.F., A. Tanaka, Y.Z., W.S., C.H., S.K., K.I., and M.Y. performed animal experiments; and Y.A., H.Y., D.I., M.N., and Y.T. wrote the manuscript, with approval from all coauthors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hiromi Yamazaki, Department of Cancer Pathology Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University 2-2, Yamadaoka, Suita, 565-0871, Japan; email: yamazaki.hiromi@patho.med.osaka-u.ac.jp; and Daichi Inoue, Department of Cancer Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine and Frontier Biosciences, Osaka University, Suita, 565-0871, Japan; email: d-inoue@patho.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

Y.A. and H.Y. contributed equally to this study.

RNA sequencing data have been uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE267189 and GSE267190).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Dysregulation of redox control by Trsp KO disrupts B-cell differentiation and transcriptional program. (A) Frequency of pre–pro-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19–CD43+), pro-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+CD43+), pre-B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM–CD19+CD43–), and immature B (CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–IgM+CD19+CD43–) cells in the BM of control and Trsp KO mice (n = 3 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (B) Representative image of polymerase chain reaction amplification. pre-B cells were isolated from BM by cell sorting, and Igh V(D)J gene rearrangement was determined by polymerase chain reaction amplification with Gapdh as a loading control (n = 2 per group). (C) Frequency of pre-B cells in the BM of each group categorized by age (young [age <20 weeks], n = 3 mice per group; aged [81 weeks], n = 5 mice per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (D) MFI of C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining in pre-B and immature B cells in the BM cells of aged control mice and aged Trsp KO mice (n = 5 mice per group; age 81 weeks). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (E) Heat map showing genes that regulate neutrophil and B-cell differentiation evaluated by RNA-seq in Trsp KO BM pre-B cells. The listed genes are from gene ontology biological process. Neutrophil includes neutrophil degranulation (GO:0043312) and Cebpa; B lymphocyte includes lymphocyte differentiation (GO:0030098), lymphocyte differentiation (GO: 0030098), regulation of B-cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050855), B-cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050853), regulation of B-cell proliferation (GO:0030888), and Ebf1, Irf4, and Irf8 (n = 4 per group). (F) GSEA enrichment plot for upregulate genes in RNA-seq of Trsp KO vs control in pre-B cells (n = 4 per group). (G) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. LSK cells were sorted from the BM of Trspfl/fl or Trspfl/fl: R26-CreERT2 mice, expanded until day 6, and cultured under B-cell differentiation conditions with OP-9 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 and FLT3-L. Cells were treated with 4-OHT for 24 hours on day 5. On day 20, they were analyzed by flow cytometry. (H) The frequency of B220+, B220+CD19+, and CD11b+ cells in each group is shown. P values were calculated by 1-way ANOVA test. (I) Schematic of BM transplantation assays. CD3–CD11b–Gr-1–Ter-119–CD19+IgM– (pro-B/pre-B) BM cells sorted from the BM of control (Trspfl/fl) or Trsp KO (Trspfl/fl: Mx1-Cre) mice at 8 weeks after pI-pC injection, with rescue cells (CD45.1+ whole BM cells) injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice. (J) Flow cytometric profiles for B220+ and CD11b+ in respective conditions and frequency of CD45.2+B220+ and CD45.2+CD11b+ cells in the BM of each group were assessed 1 month after transplantation (n = 5 per group). P values were calculated by a 2-sided Student t test. (K) The appearance of donor pro-B/pre-B–derived CD45.2+CD11b+ fractions in recipient PB is shown in each group (defined as >0.3% in live PB cells). P values were calculated using Fisher exact test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. EtOH, ethanol; FDR, false discovery rate; FLT3-L, FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; Igh V(D)J, immunoglobulin heavy chain V(D)J; IL-7, interleukin-7; NES, normalized enrichment score; ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/145/11/10.1182_blood.2024025402/2/m_blood_bld-2024-025402-gr5ik.jpeg?Expires=1765902465&Signature=JjsxpyKw1QWJ16qut0h~7bJ1xGHQR--HqgH2kAm9f~9Vm-ZF4y9TvfJnstVF8Dj5JrUM03k6qeQcIS3q8Q3yFEKlzzsPbMu-0RzDdedyo8-eEratL3frpLmWeo40K4IhIp4-VkOipROVX-cX0FaiN3~Lb4rxWBWACkIdNGNyFX7prK~OZvsvo0Ii15aJPHmUQKSalQsa7rzapdLvbXqYfG2dSqvTCV1OtjTKmbWLKXtsg6JcTKqy0zDBfeUsyqRljJu1WETA5mIpDhymFpxwtA5dNjW3gVv7z1qn9TRdE6DnEPL6MlxU5O5pEsrhkg1ouEIm27JqDsxN11zgsGaWPA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal