Abstract

The cellular and molecular bases of platelet release by terminally differentiated megakaryocytes represent important questions in cell biology and hematopoiesis. Mice lacking the transcription factor NF-E2 show profound thrombocytopenia, and their megakaryocytes fail to produce proplatelets, the microtubule-based precursors of blood platelets. Using mRNA subtraction between normal and NF-E2–deficient megakaryocytes, cDNA was isolated encoding β1 tubulin, the most divergent β tubulin isoform. In NF-E2–deficient megakaryocytes, β1 tubulin mRNA and protein are virtually absent. The expression of β1 tubulin is exquisitely restricted to platelets and megakaryocytes, where it appears late in differentiation and localizes to microtubule shafts and coils within proplatelets. Restoring NF-E2 activity in a megakaryoblastic cell line or in NF-E2–deficient primary megakaryocytes rescues the expression of β1 tubulin. Re-expressing β1 tubulin in isolation does not, however, restore proplatelet formation in the defective megakaryocytes, indicating that other critical factors are required; indeed, other genes identified by mRNA subtraction also encode structural and regulatory components of the cytoskeleton. These findings provide critical mechanistic links between NF-E2, platelet formation, and selected microtubule proteins, and they also provide novel molecular insights into thrombopoiesis.

Introduction

Megakaryocyte differentiation culminates in the release of hundreds of platelets by mechanisms that are poorly understood.1 Use of thrombopoietin (TPO), the major cytokine regulator of megakaryocyte growth and differentiation,2 has allowed expansion and differentiation of megakaryocytes in culture, leading to cellular and molecular studies that were not previously possible.3-5Concomitantly, targeted disruption of several transcription factor genes in mice has revealed phenotypes of moderate to severe thrombocytopenia and paved the way for dissection of the transcriptional control of platelet biogenesis.6-9

The transcription factor NF-E2 binds AP-1–like sites within selected erythroid-specific cis-elements, including the β-globin locus control region.10-12 NF-E2 is a heterodimer composed of 2 basic-leucine zipper (bZip) subunits of 45 and 18 kd and functions as a sequence-specific transcriptional activator.13-16Mice lacking the hematopoietic-restricted p45 NF-E2 protein show profound thrombocytopenia associated with increased megakaryocytes and lethal hemorrhage.6 p45 NF-E2−/−megakaryocytes are polyploid and have a large cytoplasm containing abundant internal membranes but few intact granules. When cultured in vitro, these cells never develop proplatelets,17 which are considered to be the immediate precursors of blood platelets.3,18,19 Thrombocytopenia and megakaryocytosis are completely reproduced in lethally irradiated wild-type mice on hematopoietic reconstitution by p45 NF-E2−/−cells.17 Targeted disruption of the gene encoding MafG, the major binding partner of p45 NF-E2 in megakaryocytes,5also results in thrombocytopenia.9 These findings implicate NF-E2 as an essential regulator of terminal megakaryocyte differentiation and platelet formation and indicate that its transcriptional targets are expressed within megakaryocytes.

To explore the molecular basis of platelet production and release, we identified candidate transcriptional targets of NF-E2 using mRNA subtraction. The predominant cDNA in the subtracted library encodes β1 tubulin, the most evolutionarily divergent isoform of β tubulin and a hematopoietic-specific protein.20 The eukaryotic tubulins, α and β, are 2 highly homologous proteins that form the core of microtubules21; α–β tubulin heterodimers integrate into linear protofilaments that assemble into microtubules by parallel association.22 Microtubules generate intracellular forces that drive diverse cellular functions, including chromosome segregation, motility of cilia and flagella, transport of vesicles and organelles, and cell morphogenesis.23Numerous distinct α and β tubulin genes have been identified in all species21,24,25 and typically share a high degree of homology within each family. Most sequence divergence is concentrated in the carboxyl terminal region,26 which is exposed on the outer surface of microtubules and is thought to interact with microtubule-associated proteins.27-29 Most murine α and β tubulin isotypes are expressed ubiquitously, though β4 is present only in the brain and β1 only in hematopoietic tissues.20,24,30 Based on C-terminal sequence divergence, the various β tubulin isoforms harbor considerable potential for functional specificity, possibly with overlap in other cellular functions. Indeed, many studies have demonstrated that β tubulin isotypes display unique biochemical properties and are partially, but not completely, interchangeable.25,31 32

Here we show that the expression of β1 tubulin mRNA and protein is almost completely abolished in the absence of NF-E2. In normal mice this distinct β tubulin isoform is restricted in expression to platelets and megakaryocytes, where it appears late in differentiation and localizes to the microtubules and microtubule rings found in proplatelets. Restoration of NF-E2 activity in a p45 NF-E2–null megakaryoblastic cell line induces the expression of β1 tubulin mRNA and protein. Considered together, these findings provide a mechanistic link between NF-E2, formation of platelet precursors (proplatelets), and specific components of the microtubule cytoskeleton. p45 NF-E2−/− cells infected with a retrovirus containing p45 NF-E2 cDNA are rescued for both β1 tubulin expression and proplatelet formation; in contrast, the isolated expression of β1 tubulin in these cells does not restore proplatelet production in vitro. This suggests that other components of the cytoskeletal machinery may also be regulated by NF-E2.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

p45 NF-E2+/− mice were maintained on an inbred 129/Sv genetic background, and fetal liver cultures were grown as described previously.17 Whole livers were recovered from mouse fetuses between embryonic days (E)13 and E15, and single-cell suspensions were prepared by successive passage through 22- and 25-gauge needles. Fetal liver and L8057 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, Bethesda, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/Ll-glutamine, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Fetal liver cultures were further supplemented with 1% tissue culture supernatant from a fibroblast cell line engineered to secrete recombinant human TPO.33 Cultured primary megakaryocytes were harvested between the third and fifth days of culture. To generate megakaryocyte colonies in semi-solid medium, 1 to 5 × 105 fetal liver cells were cultured in 1.2 mL 0.8% methylcellulose in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium, supplemented with 30% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and 1% tissue culture supernatant from the TPO producer cell line. Proplatelet formation was examined after 7 days, when individual colonies were picked under direct microscopic observation; groups of 100 colonies were pooled for analysis.

Stably transfected L8057 cell lines were generated by electroporation of linearized plasmid constructs carrying p45 or p18 NF-E2 cDNA under control of the human elongation factor (EF)-1α promoter34 and a drug-resistance cassette. p45-Transfected cells were selected in 1 mg/mL G418 (Gibco BRL), and p18-transfected cells were selected in 100 μg/mL Hygromycin B (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Stable lines were subcloned by limiting dilution and maintained in cultures containing half the above drug concentrations.

Purification of primary megakaryocytes and hematopoietic progenitors

mRNA subtraction was performed on entire cultures of fetal liver cells in TPO, without additional purification of megakaryocytes. Other experiments were performed on purified megakaryocytes (populations containing more than 90% acetylcholinesterase-positive cells) obtained by sedimentation of concentrated cultures through 2 gradients of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1.5% and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at room temperature.4 Lin− cells were obtained by the depletion of mature blood cell lineages by incubation of fetal liver cells for 30 minutes at 4°C with monoclonal antibodies directed against the differentiation markers Mac-1, GR-1, B220, and TER-119 (PharMingen, Los Angeles, CA), followed by the addition of magnetic beads coated with sheep antirat IgG (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) for 30 minutes at 4°C and the magnetic removal of bound cells.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed according to standard protocols.35 Cell extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and incubated with 1:1000 dilution of either anti-p45 NF-E2, anti-Tal-1 (provided by Richard Baer, University of Texas), or anti-β1 tubulin36 (provided by Sally Lewis and Nick Cowan, New York University) rabbit antisera for 1 hour at room temperature. After 5 washes, incubation with 1:1000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey antirabbit IgG or HRP-conjugated Protein A (Amersham Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 1 hour, and 5 additional washes, bound antibodies were detected using an enzymatic chemiluminescence kit (Amersham). Immunoblot analyses with anti-pan β tubulin (Sigma) and anti-GAPDH (Biodesign International, Kennebunk, ME) monoclonal antibodies were performed with 1:2500 dilution for the primary antibody and 1:5000 HRP-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (Amersham).

Indirect immunofluorescence

Monoclonal antibodies specific for β tubulin and fluorescein isothiocyanate and tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate conjugates of goat antirabbit and goat antimouse IgG were obtained from Sigma, and anti-β1 tubulin antiserum was obtained as above. Primary and secondary antibodies were used at 5 μg/mL and at 1:200 dilution, respectively, in PBS + 1% BSA. Cultured megakaryocytes were cyto-centrifuged at 500g for 4 minutes onto poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips, fixed in 4% formaldehyde in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco BRL) for 20 minutes, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in HBSS containing 0.1 mmol/L EGTA, and blocked with 0.5% BSA in PBS. Specimens were incubated in primary antibody for 3 to 6 hours, washed, treated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 hour, and washed again. Staining controls were processed identically except for the omission of the primary antibody. Preparations were observed with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) MRC 1024 laser scanning confocal microscope (100× differential interference contrast–apochromatic oil immersion objective) equipped with Lasersharp 3.1 software, or a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) Axiovert S100 microscope (40× phase-contrast objective) equipped with appropriate filters for fluorescein isothiocyanate and tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate fluorescence.

Subtractive hybridization

The PCR-Select cDNA subtraction kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was used for cDNA synthesis and suppressive subtractive hybridization, according to the recommended protocol. Briefly, 1 μg poly-(A)+ RNA from wild-type and p45 NF-E2−/− fetal livers cultured in the presence of TPO were used to generate double-stranded cDNA. RsaI-digested wild-type cDNA was used as the tester sample and ligated to 2 unique adapters. RsaI-digested p45 NF-E2-null cDNA was used as the driver sample without adapters. Hybridization of the tester population, with an excess of driver and an amplification of subtracted species with oligonucleotide primers corresponding to the 2 unique adapters in the tester cDNA, produced a pool of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified fragments enriched in the wild-type, but absent or reduced in the p45 NF-E2−/−, megakaryocytes. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were obtained from adult mice, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4°C, and embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were cut onto charged glass slides. Sections were cleared with xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanols, quenched in 40% methanol and 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed, and incubated with the β1 tubulin or normal rabbit (control) sera at a dilution of 1:100 for 1 hour at room temperature. After washes in PBS, sections were further incubated with donkey antirabbit–HRP antibody at 1:200 dilution for 30 minutes and washed in PBS. Peroxidase activity was revealed using 0.02% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector, Burlingame, CA) and counterstained with hematoxylin for 15 to 30 seconds. Sections were then dehydrated in graded ethanols, recleared in xylene, and mounted for microscopy.

RNA isolation, Northern blot analysis, and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated using RNAzol B (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) as recommended by the manufacturer. Northern blot analysis was performed as described.37RT-PCR analysis was conducted as described previously,6using 0.1 μCi α-[32P]dCTP as a radiotracer; the reaction products were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE and detected by autoradiography. Annealing temperature for PCR was 60°C for β tubulin and 58°C for other reactions; all reactions were confirmed to be in the linear range of amplification. Primer sequences and sizes of the amplified fragments were as follows: p45 NF-E2 (529 bp) forward 5′ AACTTGCCGGTAGATGACTTTAAT 3′ reverse 5′ CACCAAATACTCCCAGGTGATATG 3′ β1 tubulin coding sequence (492 bp) forward 5′ ATCAGGGAGGAGTACCCGGATCGGA 3′ reverse 5′ CCCGGAATATACAAGCCACAGTCAG 3′ β1 tubulin 3′untranslated region (311 bp) forward 5′ GCATGATGCTGGATTCTCAAGTCCTGG 3′ reverse 5′ CGGTGTTTCTCCGTCCACAGCAAAGT 3′ β2 tubulin (465 bp) forward 5′ CGAGCCCTGACGGTGCCCGAGCTG 3′ reverse 5′ GAACTCTCCCTCTTCCTCAGCCTG 3′ β4 tubulin (520 bp) forward 5′ CCAGGATTCGCACCCTTGACCAGC 3′ reverse 5′ AGCCTCCTCTTCGAACTCGCCCTC 3′ β5 tubulin (396 bp) forward 5′ CGCCACGGCCGGTACCTCACAGTT 3′ reverse 5′ TCCGAAATCCTCTTCCTCTTCCGC 3′ hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT, 249 bp) forward 5′ CACAGGACTAGAACACCTGC 3′ reverse 5′ GCTGGTGAAAAFFACCTCT 3′ glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 452 bp) forward 5′ ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC 3′ reverse 5′ TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA 3′ α-globin (331 bp) forward 5′ CTCTCTGGGGAAGACAAAAGCAAC 3′ reverse 5′ GGTGGCTAGCCAAGGTCACCAGCA 3′

Retrovirus production and infection of Lin− cells

The virus is based on the MPZen2 vector containing a 3′ long terminal repeat derived from myeloproliferative sarcoma virus.38 p45 NF-E2 and β1 tubulin cDNA were amplified by PCR and inserted into the polylinker site. EBNA 293 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were plated at a density of 2 × 106cells/10-cm dish in DMEM (Gibco BRL) containing 10% fetal calf serum 4 days before transfection and were fed 1 day before transfection. The retroviral vector and 2 pN8ε vectors (12 μg each) encoding the gag/pol proteins from the murine Moloney leukemia virus and the G glycoprotein from the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G)39(gift of Jay Morgenstern) were transfected using lipofectamine (Gibco BRL), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and fresh medium was added after 5 hours. Viral supernatants were collected 48, 72, and 96 hours after transfection, filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and centrifuged at 50 000g at 4°C for 2 hours. Pellets were resuspended in 1.5 mL DMEM + 10% FBS with agitation for 24 hours at 4°C and frozen at −80°C until transduction.

E13.5 mouse fetal liver cells were depleted of erythrocytes by lysis in 0.15 mol/L NH4Cl and expanded in vitro by culturing for 20 hours in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% tissue culture supernatant from the TPO producer cell line, as above, and 0.1 μg/mL c-kit ligand (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The VSV-G pseudotyped viruses were then used for infection of Lin− fetal liver cells and isolated as described above by culturing with viral supernatants in the continued presence of c-kit ligand and TPO for an additional 36 hours. After 2 washes, infected cells were cultured in TPO alone for an additional 48 hours and were monitored periodically by light microscopy for proplatelets. As judged by immunofluorescence, the transduction efficiency of retroviruses carrying either p45 NF-E2 or β1 tubulin cDNA was in the range of 5% to 10%.

Results

Isolation of a candidate effector of NF-E2 function in megakaryocytes

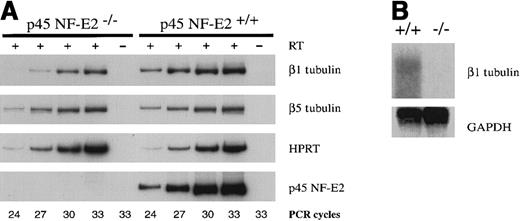

To identify putative transcriptional targets of NF-E2, we used suppressive subtractive hybridization40,41 to generate a cDNA library enriched for transcripts missing or reduced in the p45 NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes. Approximately 10% of the subtracted library contains a DNA fragment from the 3′ untranslated region of the gene encoding β1 tubulin. Expression of this mRNA is reported to be restricted to hematopoietic tissues,20including blood platelets,36 and β1 tubulin is the most evolutionarily divergent murine β tubulin isoform, sharing only 78% amino acid homology with other β tubulins.20 This raised the possibility of cell-specific functions, and the absence of a microtubule protein provides a plausible mechanism for the profound thrombocytopenia and failure of proplatelet formation in p45 NF-E2−/− mice. We examined levels of mRNA encoding each of the known murine β tubulin isotypes25 in megakaryocytes purified from wild-type and p45 NF-E2−/−cultures. Only β1 tubulin mRNA was down-regulated in p45 NF-E2−/− cells (Figure 1A; analysis of isoforms β2-β4 not shown). Northern analysis confirmed the virtual absence of β1 tubulin mRNA in p45 NF-E2−/−megakaryocytes (Figure 1B).

Specific down-regulation of β1 tubulin mRNA in the absence of NF-E2.

(A) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis on mRNA isolated from wild-type (+/+) and mutant (−/−) purified primary megakaryocytes using primers specific for the β1 and β5 tubulin isoforms, or for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) and p45 NF-E2 as controls. RT treatment of the template and numbers of PCR cycles are indicated. (B) Northern blot analysis of wild-type (+/+) and mutant (−/−) primary megakaryocytes, using β1 tubulin and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, loading control) cDNA probes.

Specific down-regulation of β1 tubulin mRNA in the absence of NF-E2.

(A) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis on mRNA isolated from wild-type (+/+) and mutant (−/−) purified primary megakaryocytes using primers specific for the β1 and β5 tubulin isoforms, or for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) and p45 NF-E2 as controls. RT treatment of the template and numbers of PCR cycles are indicated. (B) Northern blot analysis of wild-type (+/+) and mutant (−/−) primary megakaryocytes, using β1 tubulin and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, loading control) cDNA probes.

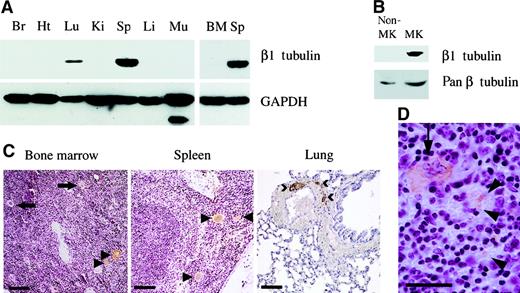

Restricted expression of β1 tubulin in late stages of megakaryocyte differentiation and platelets

Expression of β1 tubulin mRNA in adult mice is reported to be restricted to the spleen and, to a lesser extent, to the developing lung and liver.20 Using a cDNA probe derived from the unique 3′ untranslated region of the murine β1 tubulin gene, we confirmed this finding on Northern blot analysis (data not shown). We also used an isoform-specific β1 tubulin antibody36 to establish that the expression of β1 tubulin protein is restricted to the spleen in adult mice, with lower levels in the lung (Figure2A). Among all hematopoietic cells cultured from the fetal liver in the presence of TPO, this protein was detected exclusively in the megakaryocyte fraction isolated by density-gradient separation from other cell types (Figure 2B). Furthermore, immunohistochemistry on bone marrow and spleen from normal adult mice showed the β1 tubulin protein to be remarkably confined to megakaryocytes (Figure 2C). However, we detected only a weak immunoblot signal in bone marrow compared to that found in the spleen (Figure 2A), despite the known presence of megakaryocytes in both tissues, which suggested a significant contribution toward the spleen signal from sequestered blood platelets. This was confirmed by immunohistochemical analysis of the spleen (Figure 2C,D), in which extramegakaryocytic staining was restricted to platelet-sized particles found interspersed with fully differentiated erythrocytes within sinusoids in the red pulp. Significantly, only large cells morphologically identifiable as mature megakaryocytes showed detectable levels of β1 tubulin; immature megakaryocytes expressed little, if any, β1 tubulin. This finding strongly suggests that the β1 isoform appears in late stages of megakaryocyte differentiation. We failed to detect distinct cellular staining within bronchi, pneumocytes, or connective tissue in the lung; instead, immunostaining was confined to platelets within the vasculature (Figure 2C). Thus, β1 tubulin was detected exclusively in a subpopulation of mature megakaryocytes and in platelets observed in largest numbers in the spleen and lung.

Restricted expression of β1 tubulin.

Immunoblot analysis of (A) adult mouse tissues (Br, brain; Ht, heart; Lu, lung; Ki, kidney; Sp, spleen; Li, liver; Mu, muscle; BM, bone marrow) and (B) normal purified megakaryocytes and nonmegakaryocytic cells, using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum or monoclonal antibodies against GAPDH or all β tubulin isoforms (pan β tubulin). (C) Immunohistochemistry of adult mouse tissues using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum. Cellular staining in bone marrow and spleen is confined to a subset (arrowheads) of mature megakaryocytes (arrows point to unstained megakaryocytes). In lung, the signal derives from blood platelets within the abundant vasculature, occasionally detected as microthrombi (>). Background staining with the secondary antibody alone was negligible and is not shown. Scale bars: bone marrow, 300 μm; spleen and lung, 150 μm. (D) In the spleen, staining is noted both in megakaryocytes (arrow) and in particles most consistent with blood-derived platelets (arrowheads). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Restricted expression of β1 tubulin.

Immunoblot analysis of (A) adult mouse tissues (Br, brain; Ht, heart; Lu, lung; Ki, kidney; Sp, spleen; Li, liver; Mu, muscle; BM, bone marrow) and (B) normal purified megakaryocytes and nonmegakaryocytic cells, using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum or monoclonal antibodies against GAPDH or all β tubulin isoforms (pan β tubulin). (C) Immunohistochemistry of adult mouse tissues using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum. Cellular staining in bone marrow and spleen is confined to a subset (arrowheads) of mature megakaryocytes (arrows point to unstained megakaryocytes). In lung, the signal derives from blood platelets within the abundant vasculature, occasionally detected as microthrombi (>). Background staining with the secondary antibody alone was negligible and is not shown. Scale bars: bone marrow, 300 μm; spleen and lung, 150 μm. (D) In the spleen, staining is noted both in megakaryocytes (arrow) and in particles most consistent with blood-derived platelets (arrowheads). Scale bar, 50 μm.

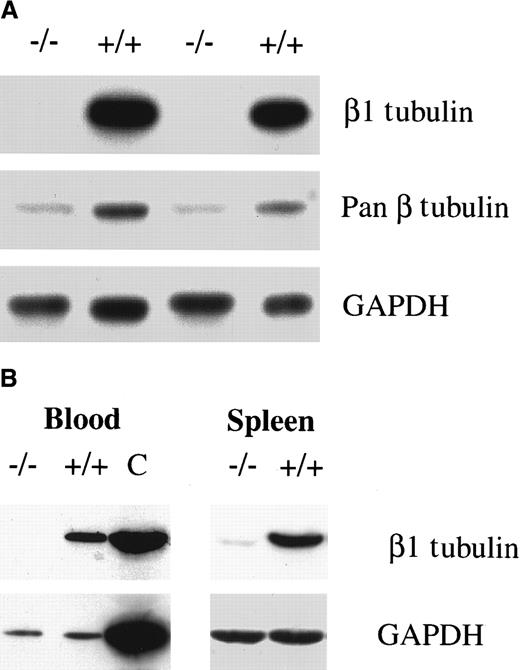

Absence of β1 tubulin protein in p45 NF-E2−/−megakaryocytes in vitro and in vivo

Cellular quantities of β tubulin mRNA and protein are regulated at 2 levels. First, there is transcriptional control that limits the expression of selected isoforms to specific cell types.30Second, a posttranslational mechanism sets the quantitative level of β tubulin through an autoregulatory pathway in which mRNA stability is governed by the concentration of the β tubulin polypeptide.42 43 Hence, the reduction of β1 tubulin mRNA in p45 NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes could in principle reflect the presence of excess free β tubulin monomers. However, the β1 isoform was undetectable in purified megakaryocytes cultured from p45 NF-E2−/− mice, and the total amount of β tubulin protein was significantly reduced (Figure3A). Thus, in the absence of NF-E2 function there is selective and profound down-regulation of the transcription of β1 tubulin, the most abundant β tubulin isoform in mature megakaryocytes. Reduced β1 tubulin expression was observed not only in cultured megakaryocytes but also in the spleen and blood of adult p45 NF-E2−/− mice (Figure 3B). Immunohistochemical analysis of the spleen and bone marrow further highlighted the absence of β1 tubulin protein in p45 NF-E2−/− mice, despite an abundance of megakaryocytes (data not shown).

Absence of β1 tubulin protein in the absence of NF-E2 in vitro and in vivo.

Immunoblot analysis of (A) purified megakaryocytes from 2 different in vitro cultures and (B) wild-type or p45 NF-E2 mutant blood (left) and spleen (right) samples, using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum, monoclonal antibodies directed against all β tubulin isoforms (pan β in A), or against GAPDH. C indicates a positive control (spleen).

Absence of β1 tubulin protein in the absence of NF-E2 in vitro and in vivo.

Immunoblot analysis of (A) purified megakaryocytes from 2 different in vitro cultures and (B) wild-type or p45 NF-E2 mutant blood (left) and spleen (right) samples, using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum, monoclonal antibodies directed against all β tubulin isoforms (pan β in A), or against GAPDH. C indicates a positive control (spleen).

β1 tubulin expression correlates with terminal phases of megakaryocyte differentiation and localizes to proplatelets and to platelet marginal bands

One feature of advanced megakaryocyte differentiation is the formation of long cytoplasmic processes, called proplatelets, which are considered to be the immediate precursors of circulating blood platelets.3,19 The absence of NF-E2 results in a failure of proplatelet formation.17 Because the generation of proplatelets involves extensive reorganization of the microtubule cytoskeleton,44 β1 tubulin is an excellent candidate mediator of thrombopoiesis. In cultures of wild-type hematopoietic cells, β1 tubulin expression was restricted to cells producing proplatelets (Figure 4A). Immature megakaryocytes and other blood lineages, including granulocytes and monocytes recognized by morphologic criteria (arrows in Figure 4A), did not express β1 tubulin. This finding complemented the in situ immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2C) in which β1 tubulin is detected only in a subset of megakaryocytes, and it was consistent with our observations17 that megakaryocytes cultured from fetal livers are functional and fundamentally similar to bone marrow–derived cells.

β1 tubulin expression is associated with megakaryocytes forming proplatelets.

(A) Immunofluorescence analysis of primary wild-type fetal liver cell cultures performed with β1 tubulin-specific antiserum (left). Cells not forming proplatelets (arrows; including other blood cell lineages and immature megakaryocytes) are not stained. A phase-contrast image of the same microscopic field is shown on the right. (B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of β1 tubulin mRNA expressed in wild-type megakaryocytic colonies forming (+) or not forming (−) proplatelets, using primers specific for β1 tubulin and GAPDH (loading control). The numbers of PCR cycles are indicated. (C-F) Immunofluorescence analysis of individual cultured megakaryocytes (C), proplatelet fragments (D, E), and blood platelets (F) with β1 tubulin-specific antiserum. Scale bar, 5 μm.

β1 tubulin expression is associated with megakaryocytes forming proplatelets.

(A) Immunofluorescence analysis of primary wild-type fetal liver cell cultures performed with β1 tubulin-specific antiserum (left). Cells not forming proplatelets (arrows; including other blood cell lineages and immature megakaryocytes) are not stained. A phase-contrast image of the same microscopic field is shown on the right. (B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of β1 tubulin mRNA expressed in wild-type megakaryocytic colonies forming (+) or not forming (−) proplatelets, using primers specific for β1 tubulin and GAPDH (loading control). The numbers of PCR cycles are indicated. (C-F) Immunofluorescence analysis of individual cultured megakaryocytes (C), proplatelet fragments (D, E), and blood platelets (F) with β1 tubulin-specific antiserum. Scale bar, 5 μm.

We further cultured megakaryocyte colonies in methylcellulose and carefully picked, under microscopic observation, 2 classes: colonies clearly producing proplatelets and those of equal size and apparently equal cellular maturity but not producing proplatelets. The β1 tubulin mRNA level in proplatelet-producing colonies was approximately 10-fold higher than in those without proplatelets (Figure 4B). This points to β1 tubulin as a product of late megakaryocyte maturation, corresponding to the stage at which differentiation is arrested in the absence of NF-E2.

One characteristic feature of resting mammalian platelets is the presence of a prominent peripheral microtubule coil positioned along the long axis, called the marginal band.45 Emerging evidence strongly suggests that the platelet marginal band is assembled within developing proplatelets as an integral aspect of thrombopoiesis,44 and Lewis et al36 have shown the platelet marginal band to contain β1 tubulin. We extended these findings to the realm of platelet biogenesis. A microtubule ring was consistently present at the termini of individual proplatelet filaments, and β1 tubulin localized to this structure (Figure 4C, D), which was similar to the marginal band of blood-derived platelets (Figure 4E). This specific localization of β1 tubulin to proplatelet shafts and platelet marginal bands immediately suggested a potential mechanism whereby this divergent and lineage-specific β tubulin isoform may participate in the assembly and release of blood platelets.

Expression of the β1 tubulin gene is dependent on intact NF-E2 function

The dramatic reduction in β1 tubulin mRNA levels in the absence of NF-E2 may reflect either direct transcriptional regulation by NF-E2 or simply the late differentiation block in NF-E2–null megakaryocytes. The mouse megakaryoblastic cell line L805746 shows complete lack of p45 NF-E2 protein (Figure5A) and mRNA (data not shown), whereas expression of other megakaryocyte-associated transcription factors, including Tal-1,47 is detected readily; these cells also fail to express β1 tubulin. In transfected L8057 cells showing stable expression of p45 NF-E2, however, β1 tubulin expression was restored (Figure 5A). Although the small-Maf (18 kd) component of the NF-E2 heterodimer was present in L8057 cells (data not shown), its availability might have been limiting for optimal formation of the functional transcription factor complex. Indeed, overexpression of p18/MafK in p45 NF-E2-expressing L8057 cells further increased the level of β1 tubulin protein (Figure 5A). These studies in a megakaryocyte cell line suggest a critical requirement for NF-E2 in the expression of β1 tubulin. Interestingly, a small fraction of NF-E2–expressing L8057 cells also went on to generate proplatelets in culture (K.S.W., R.A.S., unpublished data).

Dependence of β1 tubulin expression on NF-E2.

(A) NF-E2–dependent expression of β1 tubulin in the megakaryocytic cell line L8057. Stable subclones that do not express p45 NF-E2 or express p45 NF-E2 alone or in combination with the small-Maf p18 subunit (designated as Neo, p45, or p45 + p18, respectively) have been generated. Expression of β1 tubulin protein is absent in the parental or mock-transfected lines and is restored in p45-expressing subclones and, to a greater extent, in subclones that overexpress both p45 and p18 proteins. Immunoblots using a monoclonal antibody reactive against all β tubulin isoforms (pan β) or rabbit anti-Tal1 serum are included as loading controls. Anti-p45 NF-E2 antibody reveals the absence of p45 protein in mock-transfected L8057 cells (Neo) (B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of β1 tubulin mRNA levels in embryonic (primitive) erythrocytes purified from p45 NF-E2−/− and control (wild-type) yolk sacs. Equal loading of RNA is confirmed by PCR for the red blood cell–specific α-globin transcript, and the numbers of PCR cycles are indicated.

Dependence of β1 tubulin expression on NF-E2.

(A) NF-E2–dependent expression of β1 tubulin in the megakaryocytic cell line L8057. Stable subclones that do not express p45 NF-E2 or express p45 NF-E2 alone or in combination with the small-Maf p18 subunit (designated as Neo, p45, or p45 + p18, respectively) have been generated. Expression of β1 tubulin protein is absent in the parental or mock-transfected lines and is restored in p45-expressing subclones and, to a greater extent, in subclones that overexpress both p45 and p18 proteins. Immunoblots using a monoclonal antibody reactive against all β tubulin isoforms (pan β) or rabbit anti-Tal1 serum are included as loading controls. Anti-p45 NF-E2 antibody reveals the absence of p45 protein in mock-transfected L8057 cells (Neo) (B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of β1 tubulin mRNA levels in embryonic (primitive) erythrocytes purified from p45 NF-E2−/− and control (wild-type) yolk sacs. Equal loading of RNA is confirmed by PCR for the red blood cell–specific α-globin transcript, and the numbers of PCR cycles are indicated.

Mice lacking p45 NF-E2 show only mild red blood cell abnormalities.48 If reduced β1 tubulin in NF-E2 knockout mice simply reflects the late block in megakaryocyte differentiation, rather than direct transcriptional regulation, then β1 tubulin mRNA levels would not be expected to be reduced in erythroid cells, in which a comparable differentiation arrest is not evident. Indeed, the known presence of β1 tubulin within marginal microtubule bands in chicken erythrocytes49 50 raises the possibility that expression of this gene in 2 closely related blood cell lineages is regulated by the same transcription factor, NF-E2. β1 tubulin is absent from adult mammalian erythrocytes, and the levels of mRNA and protein in normal embryonic, nucleated red blood cells are very low (data not shown). These low levels of β1 tubulin mRNA in embryonic erythrocytes purified from yolk sacs are further reduced in cells from p45 null embryos compared with wild-type embryos (Figure 5B). This experiment, in which the possibility of yolk sac contamination by maternal platelets was carefully excluded, further supports a role for NF-E2 in transcriptional regulation of the β1 tubulin gene.

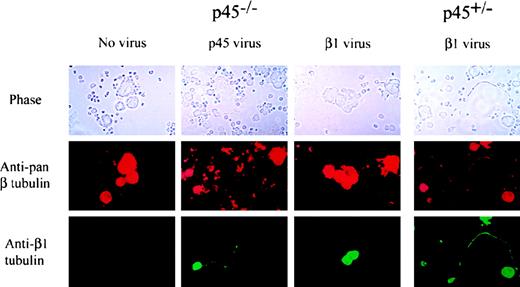

In the absence of NF-E2, β1 tubulin is not sufficient to restore proplatelet formation

Considered together, the above observations implicate β1 tubulin as a specific and possibly essential component of the cellular machinery for platelet formation and release. To investigate the possibility that the absence of β1 tubulin alone might account for profound thrombocytopenia in p45 NF-E2−/− mice, we attempted to rescue the cellular phenotype of failure of proplatelet formation in vitro. Hematopoietic progenitors (Lin− cells) from wild-type or p45 NF-E2−/− fetal liver cells were induced to proliferate in the presence of TPO and the c-kit ligand, infected with retroviruses encoding p45 NF-E2 or β1 tubulin, then cultured in TPO alone and monitored for proplatelet formation. Despite a predictably low (5%-10%) efficiency of retroviral transduction, as judged by immunofluorescence, this experimental design permitted analysis at the level of single cells in culture. Restoration of p45 NF-E2 expression in p45 NF-E2−/− cells induced readily detectable proplatelets (Figure 6) in up to half of the p45 NF-E2–expressing cells, similar to the fraction of all mature megakaryocytes producing proplatelet in vitro.17 This result formally proves that the phenotype of p45 NF-E2 knockout megakaryocytes is a direct result of inactivation of the targeted gene rather than of inadvertent silencing of a neighboring gene locus, as has been observed in rare cases.51Reintroduction of p45 NF-E2 also restored β1 tubulin expression (Figure 6), underscoring the requirement for NF-E2 in the expression of the β1 tubulin gene. In contrast, cells transduced with β1 tubulin alone failed to produce proplatelets, despite detectable expression of the protein by immunofluorescence. p45 NF-E2+/+ cells infected with β1 tubulin-encoding virus showed no compromise in the ability to produce proplatelets, thus excluding the possibility that the β1 tubulin retrovirus is toxic to cells.

β1 tubulin expression in p45 NF-E2−/−megakaryocytes does not by itself induce the formation of proplatelets.

Wild-type (right) or p45 NF-E2−/− Lin− cells (left) were infected with retroviruses encoding p45 NF-E2 or β1 tubulin or were not infected as indicated on the top. After 3 days of culture, immunofluorescence was performed using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum (bottom) or a monoclonal antibody reactive against all β tubulin isoforms (middle). Phase-contrast images of the same microscopic field are shown for each case.

β1 tubulin expression in p45 NF-E2−/−megakaryocytes does not by itself induce the formation of proplatelets.

Wild-type (right) or p45 NF-E2−/− Lin− cells (left) were infected with retroviruses encoding p45 NF-E2 or β1 tubulin or were not infected as indicated on the top. After 3 days of culture, immunofluorescence was performed using β1 tubulin-specific antiserum (bottom) or a monoclonal antibody reactive against all β tubulin isoforms (middle). Phase-contrast images of the same microscopic field are shown for each case.

Among cDNAs isolated in the mRNA subtraction between wild-type and p45 NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes, several others encode proteins with known or plausible roles in regulating both the microtubule and the actin cytoskeletons, including pleckstrin and tropomyosin 4 (P.L., R.A.S., unpublished data). In contrast to β1 tubulin, however, expression of these genes is neither lineage specific nor completely abolished in the absence of NF-E2, suggesting that megakaryocyte expression may be only partially or indirectly regulated by NF-E2. We conclude that β1 tubulin is but one protein missing in NF-E2–deficient megakaryocytes.

Discussion

Investigating the molecular mechanisms of platelet release

Cellular and molecular regulation of platelet release by terminally differentiated megakaryocytes remain poorly understood, in part because the rarity of megakaryocytes in vivo limits the identification of cells in the act of releasing platelets. Nevertheless, many independent studies have converged on a model of thrombopoiesis that recognizes that megakaryocyte differentiation culminates in the extension of long cytoplasmic processes, designated proplatelets.18 These structures are comprised of arrays of nascent blood platelets that fragment into particles with functional properties of circulating platelets.3,19,44 The internal membranes of mature megakaryocytes are believed to provide the lipid surface necessary to produce numerous proplatelets and blood platelets,52 and experimental evidence points to a central role for microtubules. Proplatelet ultrastructure reveals the presence of microtubule bundles in the shaft,3,19,53 proplatelet formation is disrupted by drugs that interfere with microtubule function,52,54,55 and the platelet marginal band is assembled by the coiling of microtubules within proplatelets.44 Megakaryocytes from genetically thrombocytopenic mice lacking NF-E2 or GATA-1 function are defective in generating proplatelets in vitro,17 underscoring the correlation with thrombopoiesis in vivo.

To identify genes required for late megakaryocyte maturation and platelet release, we took advantage of the ability to culture large numbers of normal and p45 NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes and generated a subtraction library highly enriched for transcripts that are reduced or absent in p45 NF-E2−/− megakaryocytes. Among the differentially expressed transcripts, the gene encoding β1 tubulin was particularly attractive for detailed study for several reasons. First, a β1 tubulin cDNA fragment constitutes approximately 10% of the subtracted library, and β1 tubulin mRNA is practically undetectable in megakaryocytes lacking NF-E2. Second, β1 tubulin is a hematopoietic-specific isoform that shares much lower homology with the other β tubulins than is characteristic of this family,20 suggesting the possibility that β1 tubulin may have evolved to fulfill lineage-specific functions. Third, the absence of proplatelet formation in megakaryocytes lacking NF-E217suggests a highly plausible mechanism of NF-E2–dependent thrombopoiesis that invokes reorganization of the microtubule cytoskeleton.

Here we report that the absence of NF-E2 function is associated with a lack of β1 tubulin as a result of transcriptional down-regulation, both in primary megakaryocytes and in a megakaryoblastic cell line. Coincident with the stage at which cell differentiation is arrested in the absence of NF-E2, β1 tubulin mRNA and protein expression are observed almost exclusively in late megakaryocyte differentiation. Furthermore, the protein is largely localized to proplatelets, the critical intermediate structures missing from NF-E2–deficient megakaryocytes, and we suggest that the β1 tubulin gene may be a direct transcriptional target of NF-E2. However, β1 tubulin cDNA by itself is insufficient to rescue proplatelet formation by NF-E2–deficient megakaryocytes in vitro, suggesting that other transcriptional targets of NF-E2 are also required. These findings begin to identify the components of an NF-E2–regulated biochemical pathway of thrombopoiesis.

Role of β1 tubulin in proplatelet formation and platelet release

Tubulins are core microtubule components that belong to 2 highly conserved protein families, α and β. Because isotypes within these families share considerable amino acid sequence identity (greater than 95%; β1 tubulin is the most divergent, with 78% homology), it has been difficult to demonstrate specific functions for individual isoforms. Only the testis-specific β tubulin isotype inDrosophila is known to fulfill a specific and unique role56; β1 tubulin is predominantly incorporated into a microtubule structure called the marginal band, which functions to maintain platelet discoid shape,57 and into microtubule bundles that traverse the length of proplatelet filaments in megakaryocytes (Figure 4). This cellular localization particularly suggests the possibility of a role for β1 tubulin in the genesis and stability of mammalian blood platelets. In contrast to the usual rigidity of microtubules, the platelet marginal band is remarkably flexible and is composed of a single microtubule coiled tightly within a confined space.45 Microtubules in maturing proplatelets likely also function as the conduit for rapid transport and compartmentalization of platelet organelles, another specialized function. One possibility is that the carboxyl terminus of β1 tubulin, the region of maximum sequence diversity20 and a putative mediator of protein–protein interactions,28,29associates with other megakaryocyte-specific proteins involved in organelle transport and creation or stabilization of the marginal band. Despite these considerations, β tubulin is capable of assembling into functional mitotic spindles when expressed ectopically in HeLa cells.36 This finding does not, however, preclude the possibility of additional cell-specific functions in megakaryocytes.

One is thus left with 2 broad possibilities: either β1 tubulin fulfills important lineage-specific functions that account for its sequence divergence and its restricted pattern of expression, or β1 tubulin evolved to fulfill the spatio-temporal demand for unusually high microtubule synthesis rather than to perform unique cellular functions. Notably, each of these possibilities is consistent with a dominant role for NF-E2, either as the transcriptional regulator of a specific isoform or as a factor driving high levels of lineage- and stage-specific gene expression.

β1 tubulin in an NF-E2–dependent pathway of thrombopoiesis

The absence of β1 tubulin mRNA in p45 NF-E2-null megakaryocytes is compatible with 2 distinct modes of regulation. The β1 tubulin gene could be a direct transcriptional target of NF-E2; alternatively, it may be regulated in a stage-specific manner that precludes expression in cells with arrested terminal differentiation. Either possibility places the β1 tubulin gene within an NF-E2–dependent pathway of transcriptional regulation. Transduction of p45 NF-E2 into the mutant megakaryocytes induces β1 tubulin expression (Figure 6), and expression of β1 tubulin in a megakaryoblastic cell line is dependent on NF-E2 function (Figure 5A). Although the expression of β1 tubulin is largely restricted to megakaryocytes and platelets, it has also been detected in primitive embryonic erythrocytes in mammals and in the nucleated mature erythrocytes of nonmammalian species.58-60 This expression pattern is remarkably concordant with that of p45 NF-E2, and β1 tubulin mRNA levels are decreased in red cells isolated from p45 NF-E2−/− yolk sacs (Figure 5B). Although the physiologic significance of this finding is uncertain because protein levels are low in this cell lineage, even in wild-type mice (data not shown), the result is informative with respect to the regulation of gene expression. Our initial characterization of genomic clones of murine β1 tubulin indicates the absence of a canonical TATA box and the presence of 2 consensus NF-E2–binding sites in the 5′ flanking region of the gene (P.L., R.A.S., unpublished data); experiments are in progress to determine the functional relevance of these sites in transcriptional regulation.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the expression of β1 tubulin cDNA by itself is insufficient to restore proplatelet production in megakaryocytes that lack NF-E2 function (Figure 6). These cells are known to have at least one defect in addition to the failure of proplatelet formation, a paucity of platelet-specific granules,6 for which there is no obvious link to the absence of β1 tubulin. In addition, the expression of at least one other megakaryocyte product, thromboxane synthase, appears to depend on NF-E2.61 62 The sum of the data thus points to NF-E2 as a critical regulator of a broad program of gene expression in terminally differentiated megakaryocytes. Among these genes, the lineage-specific β1 tubulin is only one, though likely a critical, component.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally Lewis and Nick Cowan for generously providing β1 tubulin-specific antiserum and John Hartwig for support and insightful discussions. We thank Ezra Poister for superb technical assistance, Carmen Tam and Massimo Loda for help with immunohistochemistry, Hideki Sasaki for providing L8057 cells, Richard Baer for anti-Tal1 serum, Karen Kotkow for the p18 NF-E2 (MafK) plasmid construct, Paresh Vyas for use of a mouse megakaryocyte cDNA library to isolate full-length β1 tubulin cDNA, and John Hartwig, Stuart Orkin, David Pellman, and Paresh Vyas for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Supported by a fellowship from the American Society of Hematology (P.L.), a National Institutes of Health training grant (J.E.I.), the Asian Life Science Institute, Korea (S.W.K.), and awards from the Cancer Research Fund of the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation (R.A.S.) and the National Institutes of Health (R.A.S.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Ramesh A. Shivdasani, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:ramesh_shivdasani@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal