Abstract

Chronic innate immune signaling in hematopoietic cells is widely described in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and innate immune pathway activation, predominantly via pattern recognition receptors, increases the risk of developing MDS. An inflammatory component to MDS has been reported for many years, but only recently has evidence supported a more direct role of chronic innate immune signaling and associated inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of MDS. Here we review recent findings and discuss relevant questions related to chronic immune response dysregulation in MDS.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) are hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) disorders defined by somatic mutations, myeloid cell dysplasia, and ineffective hematopoiesis. Chronic inflammatory diseases associated with activated innate immune signaling pathways often precede MDS; thus a role for chronic innate immune signaling in hematopoietic cells is suspected in MDS. The innate immune system recognizes pathogens and host cellular by-products by pattern recognition receptors. Among the first pattern recognition receptors to be identified were the Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Upon ligand binding, TLRs recruit intracellular adaptors, kinases, and effector molecules. When TLR signaling is chronically activated, normal hematopoiesis is impaired and prolonged inflammation alters the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment.1 Herein, we will highlight the recent data that implicate innate immune pathway activation in the abnormal function of MDS HSCs and propose new directions for study and therapeutic intervention that are supported by this evidence.

Evidence of cell intrinsic dysregulation of innate immune signaling in MDS HSC

Expression of immune-related genes in MDS hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs)

Overexpression of immune-related genes in HSPCs is reported in >50% of MDS patients (Figure 1).2,3 In MDS HSPCs, TLRs are either mutated or overexpressed compared with healthy counterparts.4,5 Downstream effectors such as MyD88 or IRAK1 and IRAK4 kinases are also overexpressed and/or constitutively activated.5-7 Hyperactivation of TLRs, MyD88, or IRAKs is functionally relevant in MDS cells as suppression of TLR-mediated signaling in MDS CD34+ cells with an inhibitor of TLR2 or MyD88 restored the hematopoietic function of MDS HSPCs, and MDS HSPCs exhibiting activation of IRAK1 or IRAK4 are preferentially sensitive to IRAK1/4-inhibitors.5-7 Aberrant expression of TRAF6, a ubiquitin ligase that mediates signaling from several innate immune receptors, is observed in MDS HSPCs.2 TRAF6 messenger RNA is overexpressed in ∼40% of MDS CD34+ cells as compared with healthy individuals. However, downregulation of TRAF6 is also observed in a subset of MDS patients.8 The innate immune signaling pathway is tightly regulated by negative feedback mechanisms. Therefore, it is not surprising that negative regulators of innate immune signaling, such as miR-145, miR-146a, and TIFAB are deleted and/or repressed in MDS HSPCs (Figure 1).9-13 These findings indicate that dysregulation of innate immune-related genes is common in MDS HSPCs.

Cell intrinsic dysregulation of innate immune signaling in MDS HSCs. TLRs and interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)/IL1RAP recruit MyD88 and IRAK4/2 (Myddosome complex) upon ligand binding (lipopolysaccharide [LPS], S100A alarmins, and IL-1). CD14 functions as a coreceptor of TLR4 in response to LPS. Toll-interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) can also increase the efficiency of Myddosome assembly by binding MyD88. IRAK4, a serine/threonine kinase, activates IRAK2 and/or IRAK1 through IRAK4-dependent phosphorylation. IRAK1 activates the ubiquitin (Ub) ligase, TRAF6, which mediates signaling to NF-κB, MAPK, and RNA binding proteins (ie, hnRNPA1) through K63-linked Ub chains, leading to expression of proinflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 or splicing of the Rho guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein Arhgap. microRNA-146a (miR-146a) suppresses IRAK1 and TRAF6 protein expression. miR-145 suppresses TIRAP protein expression. TIFAB suppresses TRAF6 protein stability. Inflammosome activation results in caspase 1–dependent IL-1β processing and pyroptosis. Proteins and genes in green are downregulated and/or deleted in MDS. Proteins and genes in red are overexpressed and/or activated in MDS. Steps of the signaling pathway that have been pharmacologically inhibited are indicated. Adapted from Varney et al.112

Cell intrinsic dysregulation of innate immune signaling in MDS HSCs. TLRs and interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)/IL1RAP recruit MyD88 and IRAK4/2 (Myddosome complex) upon ligand binding (lipopolysaccharide [LPS], S100A alarmins, and IL-1). CD14 functions as a coreceptor of TLR4 in response to LPS. Toll-interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) can also increase the efficiency of Myddosome assembly by binding MyD88. IRAK4, a serine/threonine kinase, activates IRAK2 and/or IRAK1 through IRAK4-dependent phosphorylation. IRAK1 activates the ubiquitin (Ub) ligase, TRAF6, which mediates signaling to NF-κB, MAPK, and RNA binding proteins (ie, hnRNPA1) through K63-linked Ub chains, leading to expression of proinflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 or splicing of the Rho guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein Arhgap. microRNA-146a (miR-146a) suppresses IRAK1 and TRAF6 protein expression. miR-145 suppresses TIRAP protein expression. TIFAB suppresses TRAF6 protein stability. Inflammosome activation results in caspase 1–dependent IL-1β processing and pyroptosis. Proteins and genes in green are downregulated and/or deleted in MDS. Proteins and genes in red are overexpressed and/or activated in MDS. Steps of the signaling pathway that have been pharmacologically inhibited are indicated. Adapted from Varney et al.112

Functional evidence of innate immune signaling dysregulation in MDS

Del(5q) as a paradigm for chronic innate immune signaling in MDS.

Although there is plenty of evidence that innate immune-related genes are dysregulated in MDS HSPCs, the first hint at a link between chronic innate immune signaling and MDS emerged from population-based studies that revealed an increased risk of MDS in patients with chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.14 However, initial evidence that innate immune pathway activation is causal in MDS came from work related to the del(5q) MDS genes, miR-146a and TIFAB (Figure 1). Deletion of miR-146a increases TRAF6 messenger RNA levels and translation, while loss of TIFAB increases TRAF6 protein stability, thus resulting in overexpression and activation of TRAF6 in MDS HSCs.9,11 miR-146a resides on 5q33.3 and is deleted in 80% of all del(5q) MDS.15 Low expression of miR-146a also occurs in >25% of MDS patients independent of cytogenetic status9,16,17 and is part of an MDS diagnostic miRNA signature.16 Deletion of miR-146a in mouse hematopoietic cells results in myeloid expansion, and then in BM failure, MDS, and/or leukemia.18-20 TIFAB resides within 5q31.1, which is deleted in nearly all cases of del(5q) MDS. In an independent study, TIFAB was identified by a retroviral insertional mutagenesis screen as a target in del(5q) myeloid neoplasms.21 Tifab-deficient mice develop mild hematopoietic defects and occasionally BM failure.11 However, hematopoietic-specific deletion of Tifab and miR-146a together results in a highly penetrant BM failure, which better recapitulates human del(5q) MDS.10 Changes in gene expression of other 5q genes are also associated with innate immune signaling. For instance, loss of another 5q gene, miR-145, results in derepression of Mal/TIRAP, a protein adaptor that lies in the TLR-MyD88 pathway (Figure 1).9,12 DIAPH1, which encodes mDia1, is located on 5q31.3. mDia1-deficient mice either alone or when codeleted with miR-146a exhibit an age-dependent granulocytopenia and myeloid dysplasia through increased TLR4 signaling (Figure 1).22 Codeletion of mDia and miR-146a results in anemia and ineffective erythropoiesis mediated by elevated tumor necrosis factor α and IL-6, linking a clinical aspect of MDS with chronic inflammation.22 On the other hand, a gene overexpressed from the intact 5q allele, SQSTM1/p62, that activates TRAF6, is essential for the proliferation and viability of miR-146a-deficient HSPC.23 As an indirect mechanism of innate immune activation in del(5q) MDS, loss of RPS14, a 5q gene encoding for a ribosomal protein, contributes to a p53-dependent increase of the endogenous TLR ligands S100A8/A9 (Figure 2).24 These findings underscore the intricate signaling mechanisms that support innate immune signaling in del(5q) MDS through dysregulation of neighboring innate immune-related genes.

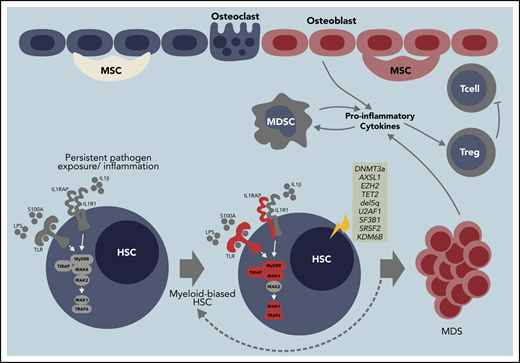

Model of innate immune signaling dysregulation in the pathogenesis of MDS. Certain diseases and conditions, such as aging, autoimmune disorders, chronic infections, and/or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), can induce innate immune signaling dysregulation in HSCs in part by creating an inflammatory BM microenvironment characterized by increased alarmins and/or cytokines. Development of MDS may occur by at least 2 independent mechanisms. (1) CHIP-associated mutations (ie, DNMT3a or TET2) occur in HSCs by innate immune independent mechanisms and drive the expansion of myeloid-biased HSC leading to altered innate immune signaling and development of MDS. (2) Prolonged innate immune signaling caused by clonally expanded myeloid-biased HSCs directly increases the risk of acquiring mutations (ie, CHIP mutations) contributing to MDS. Innate immune signaling dysregulation at the MDS stage occurs through cell-intrinsic (ie, increased cell death via pyroptosis) and cell-extrinsic mechanisms (ie, cytokines and alarmins stimulation from macrophage and myeloid derived suppressor cells [MDSCs]). As a result of altered innate immune signaling, MDSCs also promote regulatory T cell (Treg) activation to limit T-cell surveillance.

Model of innate immune signaling dysregulation in the pathogenesis of MDS. Certain diseases and conditions, such as aging, autoimmune disorders, chronic infections, and/or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), can induce innate immune signaling dysregulation in HSCs in part by creating an inflammatory BM microenvironment characterized by increased alarmins and/or cytokines. Development of MDS may occur by at least 2 independent mechanisms. (1) CHIP-associated mutations (ie, DNMT3a or TET2) occur in HSCs by innate immune independent mechanisms and drive the expansion of myeloid-biased HSC leading to altered innate immune signaling and development of MDS. (2) Prolonged innate immune signaling caused by clonally expanded myeloid-biased HSCs directly increases the risk of acquiring mutations (ie, CHIP mutations) contributing to MDS. Innate immune signaling dysregulation at the MDS stage occurs through cell-intrinsic (ie, increased cell death via pyroptosis) and cell-extrinsic mechanisms (ie, cytokines and alarmins stimulation from macrophage and myeloid derived suppressor cells [MDSCs]). As a result of altered innate immune signaling, MDSCs also promote regulatory T cell (Treg) activation to limit T-cell surveillance.

TRAF6 signaling hub underlies aberrant hematopoiesis in MDS.

In addition to its role in del(5q) MDS, TRAF6 expression is dysregulated in non-del(5q) MDS HSPCs. Overexpression of TRAF6 at disease-relevant levels in hematopoietic cells is sufficient to induce HSC defects in mice that are cell-intrinsic and associated with myeloid-biased differentiation.8 Although NF-κB is associated with TRAF6 function in immune effector cells, classic inflammatory genes are not preferentially upregulated in TRAF6-overexpressing HSPCs, suggesting that the hematopoietic phenotype following TRAF6 overexpression is not exclusively associated with activation of canonical NF-κB and inflammation. TRAF6 ubiquitinates the RNA binding protein hnRNPA1, and consequently, ubiquitinated hnRNPA1 induces aberrant splicing of Arhgap1, a negative regulator of Cdc42 whose activation mediates hematopoietic defects in TRAF6-overexpressing HSCs and MDS (Figure 1).8,25 According to genetic studies, the TRAF6 dosage impacts HSC function independent of overt infection.8,26,27 Multiple independent mechanisms contribute to hyperactivation of TLR signaling in MDS, many of which converge on TRAF6. Nevertheless, deeper insight is needed to identify the molecular consequences of TRAF6 activation in HSCs that contribute to MDS.

Inflammasome signaling as a driver of MDS.

The inflammasome consists of a family of Nod-like receptors (NLRs), which can lead to inflammatory-mediated cell death called pyroptosis.28 Of the NLR family, NLRP3 has been implicated in pyroptosis in MDS.29 Interestingly, NLRP3 is activated by diverse damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signals, including S100A8 and S100A9 (Figure 1). S100A9 and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in response to NLRP3 activation mediate pyroptosis and β-catenin activation in MDS. In addition to activation by DAMPs, inflammasome signaling is associated with common mutations in MDS, including U2AF1, SRSF2, SF3B1, ASXL1, and TET2, which all contribute to activation of NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis.29 Importantly, inhibiting the inflammasome restores normal hematopoiesis29 and protects against the development of cardiovascular disease in TET2-deficient mice.30 TRAF6 is involved in TLR-mediated priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome in BM-derived macrophages,31 suggesting that TLR signaling via TRAF6 is also linked to inflammasome activation in MDS.

Activation of immune receptors in MDS.

The best-studied TLR in MDS is TLR4 and its ligands LPS and S100A8/A9. Administration of low concentration levels of LPS in mice, meant to model chronic infection, results in myeloid-biased differentiation and loss of HSC fidelity.32 Sustained activation of TLR4 correlates with ROS-mediated DNA damage, suggesting that chronic TLR4 signaling can directly result in accumulation of genotoxicity and contribute to malignant transformation.33 Indeed, LPS was shown to induce MDS in mice with loss of the del(5q) gene mDia1, which corresponds with increased expression of the TLR4 cofactor, CD14 (Figure 1).34 TLR2 is also implicated broadly in MDS. Activation of TLR2 leads to proliferation of HSCs in mice35 and increased apoptosis and impaired erythroid differentiation of human CD34+ BM cells.5,36, Moreover, a somatic mutation of TLR2 is associated with enhanced innate immune signaling in MDS.5 Somewhat unexpectedly, a recent study suggests that TLR2 signaling has a protective role against leukemic transformation in a mouse model of MDS.37 Mice expressing NUP98-HOXD13 (NHD13 mice) developed leukemia more rapidly when crossed with Tlr2- or MyD88-deficient mice. In the NHD13 model, TLR2 appears to be important for the MDS phase of the disease, but its loss may accelerate transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Studies of TLR2 deficiency in additional models of MDS are warranted. Of note, murine models exhibit expression patterns for several TLRs that are distinct from humans, and species-specific differences in recognition of TLR ligands have been reported.38-40 Moreover, TLR signaling is sensitive to the origin, purity, and concentration of the ligand; as such, careful interpretation of experiments using TLR ligands to model chronic inflammation is necessary. Despite these caveats, human HSPCs also respond to TLR stimulation resulting in increased proliferation and myeloid differentiation,41,42 suggesting that the overall effects of innate immune signaling in human HSPCs resemble those observed in mice.

Alterations in epigenetic genes and their effects on innate immune signaling.

EZH2, a catalytic component of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) that adds repressive methyl marks to H3K27, is mutated or downregulated in MDS.43 On the other hand, KDM6B (JMJD3), which demethylates H3K27, is overexpressed in MDS CD34+ cells,44 and its expression can be induced with TLR2 ligands.5 In certain contexts, EZH2 is implicated as a negative regulator of innate immune signaling associated with viral sensing in part through inhibition of RIG-I or with degradation of TRAF6.45,46 KDM6B regulates several transcription factors of the innate immune response, and its expression is increased by NF-κB in response to microbial stimuli.47 In MDS patients, KDM6B mediates transcription of multiple genes involved in NF-κB activation, suggesting that KDM6B is a feed-forward activation node of innate immune signaling in HSPCs.44 The connections between these 2 epigenetic regulators and immunity were recently reviewed.48

Innate immune signaling and clonal hematopoiesis (CH)

HSCs represent a functionally heterogeneous cell population49-52 ; however, myeloid-biased differentiation is observed in chronic inflammation, autoimmune diseases, and aging,53,54 coinciding with diminished HSPC heterogeneity.55 The expansion of HSC clones at a rate disproportionately greater than other clones is known as CH (Figure 2). Increasing evidence suggests that innate immune signaling in HSPCs acts as a selective pressure contributing to CH. Throughout the life of an organism, HSCs encounter and respond to pathogens,56,57 resulting in rewiring of transcriptional networks driving myelopoiesis1,58-61 and “trained” innate immune memory.62,63 The expanded myeloid-biased long-term HSCs following an immune challenge exhibit enrichment of innate immune-related genes at the expense of gene expression related to lymphopoiesis.62 These observations suggest that clonal expansion of myeloid-biased HSCs with “trained” innate immune memory preceding MDS might be driven by continuous innate immune signaling. Indeed, myeloid-biased hematopoiesis is observed in immune-related diseases that often lead to MDS, such as arteriosclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, as a result of TLR4-mediated signaling in HSPCs.53,64-66 Although the clonally expanded myeloid-biased HSCs might not be malignant per se, they might serve as a conduit for the development of myeloid neoplasms. We envision development of MDS by at least 2 independent mechanisms: (1) prolonged innate immune signaling caused by clonally expanded myeloid-biased HSCs directly increases the risk of acquiring mutations contributing to MDS; or (2) somatic mutations occur in HSCs by innate immune independent mechanisms and drive the expansion of myeloid-biased HSCs leading to altered innate immune signaling and development of MDS (Figure 2).

Innate immune signaling as a driver of CHIP mutations

HSCs accumulate somatic mutations with age in otherwise healthy individuals.67 Although most of these mutations are inconsequential, HSCs can acquire mutations providing a clonal advantage leading to CHIP.68,69 Although individuals with CHIP might never develop hematopoietic malignancies, they are at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and MDS. The most common mutations identified in CHIP occur in DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1,70,71 which are also prevalent in MDS. The mechanisms by which CHIP mutations are acquired are not clearly discerned. Bacterial genotoxins and ROS resulting from chronic innate immune signaling are known to induce genomic mutations in hematopoietic cells.33,72-74 Despite evidence demonstrating that chronic innate immune signaling can induce genomic instability, acquisition of CHIP mutations because of inflammatory stressors has not been reported.

CHIP mutations as drivers of innate immune signaling

Mutations of DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 alter innate immune signaling through various mechanisms. TET2 negatively regulates expression of proinflammatory cytokines and interferons in immune cells,75-77 thus indicating that inactivation of TET2 increases innate immune signaling. In support of these observations, TET2 mutations in macrophages are associated with elevated IL-1β-NLRP3 signaling,30,76,78,79 a driver of MDS. Preleukemic myeloproliferation following Tet2 deficiency depends on IL-6 signaling and occurs only in a subset of mice that experienced bacterial infection from barrier dysfunction in the small intestine, indicating that infection-associated innate immune activation is required for myeloproliferation in cells bearing a CHIP-associated mutation.80 DNMT3A mutations have also been implicated in regulating innate immune signaling. DNMT3A-deficient mice exhibit increased interferon α/β and higher mortality rates after challenge with RNA viruses81 ; however, the mechanism by which DNMT3A regulates innate immune signaling remains unknown. Evidence for ASXL1 mutations regulating innate immune signaling is scarce. One study reported that mutant ASXL1 induces a myeloid differentiation block by reducing CLEC5 expression,82 a C-type lectin receptor activated by glycans present in microorganisms that is downregulated in MDS patients.82 Further studies are needed to determine if ASXL1 plays a role in regulating innate immunity.

HSPC-extrinsic mechanisms associated with innate immune signaling in MDS

Ineffective hematopoiesis and clonal dominance are not limited to cell-intrinsic mechanisms of the MDS clone. Recent evidence has revealed that age- and disease-related microenvironment changes within the MDS BM niche contribute to ineffective hematopoiesis. In this section, we summarize the recent perspectives on the role of aberrant innate immune signaling emerging from HSPC-extrinsic mechanisms in MDS.

Immune cells

MDSCs secrete immunosuppressive cytokines to reduce effector T-cell proliferation. MDSCs are increased in MDS BM, and the magnitude of MDSC abundance is an indicator of poor prognosis in MDS.83 Interestingly, MDSCs in MDS patients do not harbor the same somatic mutations as the MDS clone, indicating that the MDSCs arise from distinct hematopoietic clones.84 MDSCs are activated by binding of CD33 to S100A9, a DAMP abundantly expressed by MDSCs.85 In support of a model in which MDSC-derived S100A9 expression contributes to MDS, S100A9 transgenic mice develop an MDS-like disease that coincides with increased activation of MDSCs.84 In contrast, blocking S100A9 signaling restored normal hematopoiesis, thus implicating MDSCs as initiators of the MDS phenotype.84 Nevertheless, it remains unknown how MDSCs and MDSC-secreted DAMPs affect HSPCs and contribute to clonal selection.

The role of granulocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells is less clear in MDS.86-88 As indicated previously, deletion of mDia1 or TET2 results in increased innate immune signaling in mature myeloid cells. The contribution of the adaptive immune system, specifically T-cell surveillance, in MDS BM has not been as extensively documented. In low-risk MDS, the decreased number of Treg’s is associated with T effector cell targeting of HSPCs, whereas the increased number of Treg’s in high-risk MDS results in immunosuppression.89,90 This switch in immune surveillance correlates with changes in the cytokine milieu from a proinflammatory state in low-risk patients to anti-inflammatory state in high-risk MDS and AML patients.91

Mesenchymal stroma

The nonhematopoietic cells of the BM are composed of blood vessels and the mesenchymal stroma derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Endothelial cells and mesenchymal cells function to form a niche that is required for HSPC function. Although still somewhat inconclusive, a few studies point to a role of mesenchymal cells in MDS. For example, engraftment of human MDS HSPCs in immune-deficient mice is enhanced by cotransplantation with patient-derived mesenchymal cells.92-94 The role of innate immune signaling in MSC-mediated support for MDS HSPCs is reinforced by the findings that patient-derived MSCs exhibit higher inflammatory signaling compared with healthy controls and that MDS HSPC function is enhanced by coculture with LPS-stimulated stromal cells.66,93 Another study found that a mouse model of MDS could be engrafted into aged recipient mice more efficiently than in young mice, indicating that aged BM stroma is more conducive to MDS.22 Although these studies support a role for the mesenchyme in sustaining MDS, other studies suggest that the mesenchyme is important for the initiation of MDS. Mice bearing mesenchymal-specific deletion of Dicer1 or Sbds have increased inflammation in their BM, correlating with elevated secretion of S100A9, and development of MDS-like defects.66,95 Interestingly, DICER1 and SBDS are downregulated in mesenchymal cells of MDS patients,96 and DICER1 downregulation was implicated in increased senescence of MDS mesenchymal progenitor cells.97 Patients with Schwachman-Diamond syndrome have inherited mutations in SBDS and an elevated incidence of MDS; however, hematopoietic-specific deletion of Sbds failed to induce hematologic malignancies in mice. In contrast, mesenchymal-specific Sbds deletion resulted in MDS-like phenotypes, suggesting that the mesenchymal compartment is responsible for disease initiation in some MDS patients.98 A recent report described elevated WNT/β-catenin signaling in mesenchymal cells from MDS patients, and constitutive β-catenin activation in MSC-derived osteoblasts caused AML in a mouse model,99,100 suggesting that WNT signaling from the stroma also promotes disease progression. β-catenin signaling has known roles in transcriptional activation of innate immune and inflammation-associated signaling pathways, including transforming growth factor β and Notch.101 The mechanisms by which Dicer and Sbds deletion or constitutive β-catenin activation in mesenchymal cells cause increased innate immune signaling in hematopoietic cells may not be direct, but these studies collectively point to a role for abnormal mesenchymal cells as a source of innate immune signals in the BM microenvironment that may drive MDS development.

Cytokines

Elevated expression of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors is a hallmark of MDS (Figure 2). The source of these secreted factors in MDS has been demonstrated in various cell populations. As indicated previously, MDSCs secrete a host of immune-inhibitory cytokines in response to S100A9-mediated activation. Additionally, myeloid cells derived from the MDS clone secrete higher levels of cytokines.86 Cytokine profiling across large MDS cohorts has yielded conflicting reports on which cytokines are most relevant to MDS. Nevertheless, tumor necrosis factor α, transforming growth factor β, interferon γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor are commonly increased in MDS patients, and in certain cases their expression correlates with disease outcome.102-105 One of the clinical features of MDS is anemia. Proinflammatory cytokines were shown to mediate hepcidin expression in the liver, which negatively regulates iron availability in erythroblasts.106 However, a direct link between hepcidin expression and MDS has not been determined. Recent reviews have described the multifaceted roles of the aforementioned cytokines in MDS and ineffective hematopoiesis.107,108

Targeting innate immune pathways in MDS

Chronic innate immune signaling in MDS HSCs and in the microenvironment provides a rationale for the development of therapies that target oncogenic innate immune pathways. There are preclinical studies demonstrating the potential of inhibiting IL-1R/TLR-IRAK-TRAF6 signaling in MDS by targeting IRAK1 and/or IRAK4 with small molecules, or IL1RAP with antibodies (Figure 1).7,109 Targeting of the S100A9-CD33-TLR4 axis restores hematopoiesis in MDS-like mouse models, in part by dampening the activity of MDSCs. As such, monoclonal antibodies to CD33 are being investigated in lower-risk MDS patients.110 A phase 1/2 trial of low-risk MDS is underway testing the efficacy of OPN-305, an antagonistic monoclonal antibody to TLR2 (#NCT02363491). Although, the initial results showed an overall response rate of 50%, completion of the trial is necessary to assess the full potential of targeting TLR2 in MDS. CX-01, which disrupts TLR4 activation by blocking 1 of its endogenous ligands, HMGB1, is also under investigation in MDS (#NCT02995655). A rationale for targeting innate immune pathways is supported by the efficacy of lenalidomide in del(5q) MDS. Lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug derived from the chemical structure of thalidomide, exhibits multiple effects on the immune system.111 Given that innate immune signaling is activated not only in the MDS clone but also in the microenvironment, there is a growing enthusiasm to target these pathways in MDS. Although these therapies may or may not eliminate the neoplastic clone directly, the simultaneous attenuation of both MDS clonal expansion and microenvironmental innate immune signaling, which is likely essential for MDS clonal selection, may provide a clinical response through the outgrowth of healthy HSCs and restoration of normal hematopoiesis.

Conclusions

An inflammatory component to MDS has been reported for more than a decade, but only recently has evidence supported a more direct role of chronic innate immune signaling and associated inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of MDS. Despite the mounting data demonstrating that innate immune pathways have been co-opted in MDS HSPCs and activated in the microenvironmental cells, there remain many unanswered questions. Of most importance, is chronic immune signaling an initiating and/or a modifying event in MDS? How does dysregulation of innate immune signaling cooperate with other genetic and/or molecular defects observed in MDS? Given that innate immune pathways typically activate NF-κB and MAPK signaling, it is imperative to determine the role of these pathways in MDS clonal dominance vs dyshematopoiesis. Finally, it is important to distinguish between the effects of innate immune signaling on HSCs vs immune cells in MDS.

Acknowledgments

D.T.S. was supported by the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (Scholar Award), the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R35HL135787), and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (RO1DK113639, RO1DK102759). L.B. was supported by the American Society of Hematology (Scholar Award) and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES007250). T.M.C. was supported by the American Society of Hematology (Scholar Award) and the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (F32HL143993).

Authorship

Contribution: L.B., T.M.C., and D.T.S. designed and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel T. Starczynowski, Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: daniel.starczynowski@cchmc.org.

REFERENCES

Author notes

L.B. and T.M.C. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Cell intrinsic dysregulation of innate immune signaling in MDS HSCs. TLRs and interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)/IL1RAP recruit MyD88 and IRAK4/2 (Myddosome complex) upon ligand binding (lipopolysaccharide [LPS], S100A alarmins, and IL-1). CD14 functions as a coreceptor of TLR4 in response to LPS. Toll-interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) can also increase the efficiency of Myddosome assembly by binding MyD88. IRAK4, a serine/threonine kinase, activates IRAK2 and/or IRAK1 through IRAK4-dependent phosphorylation. IRAK1 activates the ubiquitin (Ub) ligase, TRAF6, which mediates signaling to NF-κB, MAPK, and RNA binding proteins (ie, hnRNPA1) through K63-linked Ub chains, leading to expression of proinflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 or splicing of the Rho guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein Arhgap. microRNA-146a (miR-146a) suppresses IRAK1 and TRAF6 protein expression. miR-145 suppresses TIRAP protein expression. TIFAB suppresses TRAF6 protein stability. Inflammosome activation results in caspase 1–dependent IL-1β processing and pyroptosis. Proteins and genes in green are downregulated and/or deleted in MDS. Proteins and genes in red are overexpressed and/or activated in MDS. Steps of the signaling pathway that have been pharmacologically inhibited are indicated. Adapted from Varney et al.112](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/132/15/10.1182_blood-2018-03-784116/4/m_blood784116f1.png?Expires=1767759523&Signature=VJ6360s~JBFt4VM0PEjgn~mrQqxbUhNYWmflumwrc0Pl8jrZomURg8Og9IySV1NIdwHSI2MTQMormQMbRv6wW8aXq10bviy~ZFtAW83SWjm~~SLn~e4PIdt7VnWX57wXAL64xwRa5-eHo-60M7-syNNu8-IBmekwwznhzm8nGD0IjhNRfVwBTntOJFLi8852s62IvrGmIwWQlPQ-0uMXcxG1Jc5RBqWpKPVZglIzErcQw4KZsAG4-PjjlgNLBaAeU3Bf24X56FO6-4HK3vngm7hUfD7z2LNvYpAu-7XgC~BMd-ChsLJLLefb7518VfsZ0kiayWbmffND1BTmJUNeEA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. Model of innate immune signaling dysregulation in the pathogenesis of MDS. Certain diseases and conditions, such as aging, autoimmune disorders, chronic infections, and/or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), can induce innate immune signaling dysregulation in HSCs in part by creating an inflammatory BM microenvironment characterized by increased alarmins and/or cytokines. Development of MDS may occur by at least 2 independent mechanisms. (1) CHIP-associated mutations (ie, DNMT3a or TET2) occur in HSCs by innate immune independent mechanisms and drive the expansion of myeloid-biased HSC leading to altered innate immune signaling and development of MDS. (2) Prolonged innate immune signaling caused by clonally expanded myeloid-biased HSCs directly increases the risk of acquiring mutations (ie, CHIP mutations) contributing to MDS. Innate immune signaling dysregulation at the MDS stage occurs through cell-intrinsic (ie, increased cell death via pyroptosis) and cell-extrinsic mechanisms (ie, cytokines and alarmins stimulation from macrophage and myeloid derived suppressor cells [MDSCs]). As a result of altered innate immune signaling, MDSCs also promote regulatory T cell (Treg) activation to limit T-cell surveillance.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/132/15/10.1182_blood-2018-03-784116/4/m_blood784116f2.png?Expires=1767759523&Signature=H3QbGxNY83tHyw0P6bM-vmaFBITO-kNJMnwT~Q4lzPpuvN3tX-ydJGxsqkGstA0QHYkX2kZaTvmg6YyWjMxc87Eo6ps54H-k6rgh4zLjrcKlBnPKBrd4ctz7XI7KC5YzOQ31vCPx8RxA2CoesBvkcnqfoST3o1B0A0CYQWwtDV9P2w2AxXbNwE-DdhJulPCl4y6QZzABXI-2RdwAVZhf7vC51oH7tF4Rc~oMTX~o~FsuWicr-K7Uqx1DByHOTiOo5O7xDhc6Pps0MI-36oUmv9lARvxlXxffOAJXSsV9cGzqh9Vxt~gurTh3E8oayp7lsCuoZBCLybDRwsVB9lQhEQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Cell intrinsic dysregulation of innate immune signaling in MDS HSCs. TLRs and interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)/IL1RAP recruit MyD88 and IRAK4/2 (Myddosome complex) upon ligand binding (lipopolysaccharide [LPS], S100A alarmins, and IL-1). CD14 functions as a coreceptor of TLR4 in response to LPS. Toll-interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) can also increase the efficiency of Myddosome assembly by binding MyD88. IRAK4, a serine/threonine kinase, activates IRAK2 and/or IRAK1 through IRAK4-dependent phosphorylation. IRAK1 activates the ubiquitin (Ub) ligase, TRAF6, which mediates signaling to NF-κB, MAPK, and RNA binding proteins (ie, hnRNPA1) through K63-linked Ub chains, leading to expression of proinflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 or splicing of the Rho guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein Arhgap. microRNA-146a (miR-146a) suppresses IRAK1 and TRAF6 protein expression. miR-145 suppresses TIRAP protein expression. TIFAB suppresses TRAF6 protein stability. Inflammosome activation results in caspase 1–dependent IL-1β processing and pyroptosis. Proteins and genes in green are downregulated and/or deleted in MDS. Proteins and genes in red are overexpressed and/or activated in MDS. Steps of the signaling pathway that have been pharmacologically inhibited are indicated. Adapted from Varney et al.112](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/132/15/10.1182_blood-2018-03-784116/4/m_blood784116f1.png?Expires=1767760533&Signature=HoHxsRn8bKGJ4HjhlfCNbB3~bidkjHyv6Imf36cfwp~~Pngx3d8iQxZvrSYa0EmeO6BWbW-KmHw42x1hh4p6wru9ARRwy5TJYkGYnTbrpxCbQA7k8tnohjtOftuEymf1UZkbpkLhD2jJTYrK4bVFAPAIwepserUqbnwosS~eCGYYSh3qHNICWnJUj1nkajgsm4Ss7YY0d2FT-7oRzQX64W68lBeQr9P7wR2grR6QcLUE0WC-UaF6hAyWS3ct2ltD0XLEVGn82VIT77wHvuWKDPVkBd8ZisDYvxJTYb4wjDtF-ObfTpeaBy~3AvpaQf8sOu6P2u8SUe~vmdREUFIZuA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. Model of innate immune signaling dysregulation in the pathogenesis of MDS. Certain diseases and conditions, such as aging, autoimmune disorders, chronic infections, and/or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), can induce innate immune signaling dysregulation in HSCs in part by creating an inflammatory BM microenvironment characterized by increased alarmins and/or cytokines. Development of MDS may occur by at least 2 independent mechanisms. (1) CHIP-associated mutations (ie, DNMT3a or TET2) occur in HSCs by innate immune independent mechanisms and drive the expansion of myeloid-biased HSC leading to altered innate immune signaling and development of MDS. (2) Prolonged innate immune signaling caused by clonally expanded myeloid-biased HSCs directly increases the risk of acquiring mutations (ie, CHIP mutations) contributing to MDS. Innate immune signaling dysregulation at the MDS stage occurs through cell-intrinsic (ie, increased cell death via pyroptosis) and cell-extrinsic mechanisms (ie, cytokines and alarmins stimulation from macrophage and myeloid derived suppressor cells [MDSCs]). As a result of altered innate immune signaling, MDSCs also promote regulatory T cell (Treg) activation to limit T-cell surveillance.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/132/15/10.1182_blood-2018-03-784116/4/m_blood784116f2.png?Expires=1767760533&Signature=agp~cJT3xoS5l-ippSnxYaSz2NoiN1OlEs407uBjivBuScTDFBtutjJeTeLqGKVVubOdPqZT-Klf5Sb~erM3y81QMhq3dH05CL5ljgWpYEqkavn3aH3DGC7dZPXamZTbF2MLaFCBAt7k6g9y4WY3nfSHyG8W0Rr2mjagpVSj~sB~JR3GeuFU6P7QE0maOfv14t5uQ2NxrI7asPH1NwFtZF0KJKxGVTktIl3IAhXz7ATnEQKo5WV8PXBm0pDSRtYCpIIUFtZitRPzEhuxHC-LRXgiOpJ2Mmfy-UMShQHfXeMlKnz6UElXesZHPUuLO4-HYP6rF~r2hoFjr9DGlOGB~Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)