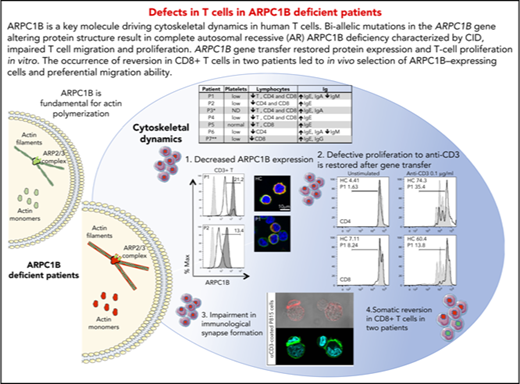

Key Points

ARPC1B deficiency alters T-cell proliferation, cytoskeleton dynamics, cell migration, and immunological synapse assembly.

Functional defects are corrected in naturally revertant and ex vivo transduced T cells.

Abstract

ARPC1B is a key factor for the assembly and maintenance of the ARP2/3 complex that is involved in actin branching from an existing filament. Germline biallelic mutations in ARPC1B have been recently described in 6 patients with clinical features of combined immunodeficiency (CID), whose neutrophils and platelets but not T lymphocytes were studied. We hypothesized that ARPC1B deficiency may also lead to cytoskeleton and functional defects in T cells. We have identified biallelic mutations in ARPC1B in 6 unrelated patients with early onset disease characterized by severe infections, autoimmune manifestations, and thrombocytopenia. Immunological features included T-cell lymphopenia, low numbers of naïve T cells, and hyper–immunoglobulin E. Alteration in ARPC1B protein structure led to absent/low expression by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. This molecular defect was associated with the inability of patient-derived T cells to extend an actin-rich lamellipodia upon T-cell receptor (TCR) stimulation and to assemble an immunological synapse. ARPC1B-deficient T cells additionally displayed impaired TCR-mediated proliferation and SDF1-α−directed migration. Gene transfer of ARPC1B in patients’ T cells using a lentiviral vector restored both ARPC1B expression and T-cell proliferation in vitro. In 2 of the patients, in vivo somatic reversion restored ARPC1B expression in a fraction of lymphocytes and was associated with a skewed TCR repertoire. In 1 revertant patient, memory CD8+ T cells expressing normal levels of ARPC1B displayed improved T-cell migration. Inherited ARPC1B deficiency therefore alters T-cell cytoskeletal dynamics and functions, contributing to the clinical features of CID.

Introduction

Actin cytoskeleton remodeling drives a number of dynamic processes, which are key to many aspects of cell biology. It relies on the rapid turnover of filaments and the assembly of large-scale meshworks. These tightly regulated mechanisms are governed by a molecular machinery composed of a set of more than a hundred actin-binding proteins.1 These proteins are endowed with different actin remodeling activities likely nucleation, elongation, capping, severing, depolymerization, and cross-linking of actin filaments. Because of the key role of actin cytoskeleton remodeling in immune cell function, its perturbation can result in autoimmunity or primary immunodeficiency (PID).2-4 In particular, the ARP2/3 complex plays an important role in actin nucleation and polymerization in blood cells. Loss of ARP2/3 complex results in decreased lamellipodia formation, defective chemotaxis, and cell migration,5 leading to abnormalities of innate and adaptive immunity and contributing to immune dysregulation. The ARP2/3 complex is activated by the WASP/WIP/CDC42 axis to induce actin polymerization and generate new branched actin filament networks in the context of cell migration, endocytosis, vesicular trafficking, and cytokinesis.6-11 Among its 7 subunits, ARPC1, a β-propeller protein with 7 blades, acts as a potential contact between the complex and an actin subunit in either the mother or the daughter filament. Two isoforms of ARPC1 have been described in humans, sharing 68% sequence identity. ARPC1B expression is restricted to hematopoietic cells,12 where it exerts a regulatory role for the assembly and maintenance of the ARP2/3 complex1,8,13,14 in driving the generation of a new actin filament from a preexisting filament.

Similarly to patients with loss-of-function mutations in the WAS gene, characterized by microthrombocytopenia, immunodeficiency, eczema, increased risk of malignancies and of autoimmune manifestations,15 dysfunctions and impaired regulation of ARPC1B may lead to immune dysregulation. Recently, 6 unrelated patients carrying distinct homozygous mutations in the ARPC1B gene were described with symptoms of infections, immune dysregulation, vascular lesions, and variable degree of bleeding.12,16,17 Platelets showed morphological and functional alterations because of impaired actin dynamics,12,16 and defects in neutrophil motility and chemotaxis with leukocytosis and bleeding tendency were documented.16 Arpc1b−/− mice display susceptibility to infections and mild vessel inflammation16 but no major T-cell alterations, and zebrafish mutants showed altered development of T cells and thrombocytes.17 Several open questions remain regarding the effects of mutations in the ARPC1B gene and the mechanisms affecting T-cell development and function in ARPC1B-mutated patients. We hypothesized that ARPC1B deficiency may lead to cytoskeleton, developmental, and functional defects in T cells, contributing to the clinical manifestations of the condition. Here we studied 6 patients of different ethnicities with combined immunodeficiency (CID) and immune dysregulation because of novel distinct homozygous mutations in the ARPC1B gene.

Methods

Patients and cell lines

Peripheral blood was obtained in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or ethical standards. Informed consents were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of San Raffaele Hospital (TIGET06, TIGET09), Ospedale Gaslini and Sheba Medical Center, National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board–approved protocol 16-I-N139, and Institutional Review Board–approved protocol 16-08-717 (CBE-SIU Universidad de Antioquia). See details of in vitro migration assay, T-cell proliferation, and transduction in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Next-generation sequencing (NGS)

Targeted sequencing (Haloplex custom kit of 200 bp; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) was performed on 630 genes among those described for PID and candidate genes18,19 in patient 1 (P1) and the family. Sequencing was performed with a MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycles) on Illumina MiSeq machine. Whole exome sequencing was performed in patients 2 to 6 (P2, P3, P4, P5, and P6) was sheared with a Covaris S2 Ultrasonicator (Covaris). See supplemental Methods for bioinformatics analysis.

Flow cytometry for ARPC1B

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or phytohemagglutinin (PHA) T-cell blasts20 were stained for lymphocyte surface markers (BD Bioscience), and intracellular staining for ARPC1B was performed after fixation and permeabilization according to described methods21,22 (see supplemental Methods). DNA was extracted from sorted subpopulations and sequenced for ARPC1B c.64+1G>C mutation. Results were analyzed by 4Peaks Electropherogram analyzer tool (Mekentosj, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). See supplemental Methods for Vbeta repertoire and modeling of ARPC1B protein mutants.

Confocal microscopy and immunological synapse (IS) assembly

Freshly isolated PBMCs were stained as described23 with ARPC1B, phalloidin, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and acquired with a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope (supplemental Methods). For IS PHA T-cell blasts were seeded on slides with preformed reaction wells (Marienfeld, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany), coated with 2 µg/mL recombinant ICAM-1/Fc chimera (R&D Systems) and 10 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (Ab) (OKT3, eBioscience). SMIFH2 pan-formin inhibitor was used at a final concentration of 50 µM. Slides were examined with LSM 710 confocal microscope (×63-1.4 oil immersion Plan-Apochromat objective; Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany). Images of randomly selected cells were acquired and analyzed by ImageJ software (supplemental Methods).

Conjugate formation

PHA T-cell blasts were stained with CellTrace Violet (ThermoFischer Scientific) and tested for conjugate formation against anti-CD3 (OKT3, 10µg/mL) coated/not P815 cells. The percentage of conjugates formation was analyzed by FlowJo software (supplemental Methods).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or median and analyzed with Graph-Pad Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad Software, la Jolla).

Results

ARPC1B mutations in patients with CID

We carried out NGS in 6 patients from unrelated families from Italy (P1 and P2), Canada (P3), Colombia (P4), Morocco (P5), and Turkey (P6) with CID. Clinical manifestations started in most patients within the first 2 months of life (supplemental Table 1) including infections, eczema, vasculitis, hepatosplenomegaly, and enterocolitis (supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Methods). All patients show T-cell lymphopenia and reduced numbers of naïve T cells; reduced platelets counts were present in 5 patients (supplemental Figure 2 and supplemental Tables 1-2). In P1 and P2, platelets abnormalities included reduced platelet size (P2) and a severe defect in PAC1 upregulation upon stimulation with adenosine-5′-diphosphate, thrombin, and collagen, whereas CD62P activation was normal (supplemental Figures 3-4 and supplemental Methods). A comparison between clinical manifestations of the disease in our patients and previously reported works12,16,17 is summarized in supplemental Table 3. Patient 7 (P7) was recently described17 and included as an ARPC1B-null patient for comparisons.

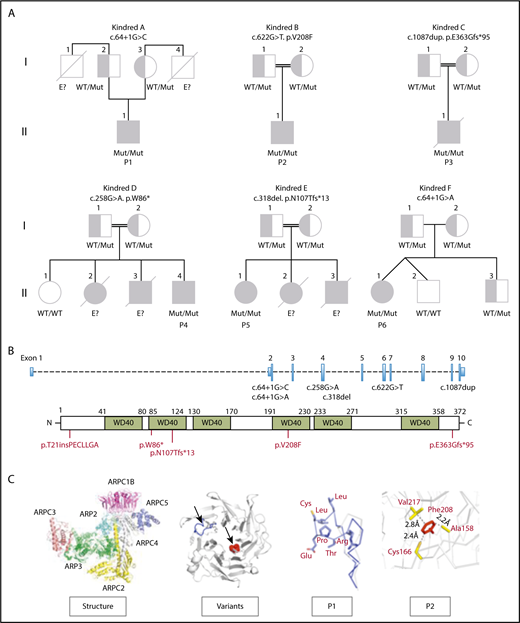

DNA was tested in the families by either targeted (P1) or whole exome sequencing (P2 to P6). Variants were sorted according to models of inheritance (autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, X-linked, or de novo mutations)24 and for their presence in well-known PID genes or in new candidate genes.19,25 Novel rare homozygous variants were found in the ARPC1B gene that has been recently associated with CID and platelet defects.12,16,17 P1 carries a homozygous splice donor variant c.64+1G>C (rs111297226, minor allele frequency <0.0001) predicted as damaging (combined annotation dependent depletion [CADD]:27.2),26-29 which inserted 21 nucleotides deriving from intron 2 (Figure 1A-B), leading to the usage of an alternative splice site with partial intron retention and maintenance of the reading frame. P2 carries a homozygous substitution at c.622G>T in exon 6, resulting in p.Val208Phe (rs371760619, minor allele frequency <0.01), predicted as a novel damaging missense mutation (combined annotation dependent depletion [CADD]:28.9). P3 carries a private homozygous duplication in exon 10, c.1087dup predicted as p.Glu363Glyfs*95 (CADD:35). In P4, a nonsense mutation in exon 4 (c.258G>A) results in an early stop codon (p.Trp86*) predicted as damaging (CADD:37). P5 carries a homozygous variant in exon 4 (c.318del) predicted as p.Asn107Thrfs*13. P6 carries a rare homozygous splice donor variants c.64+1G>A predicted as damaging (CADD:26.7). All variants were verified by Sanger, and we confirmed that both parents of the 6 cases were carriers of the respective mutations in heterozygous state, except for P5, where only the mother could be tested and no genetic material was available for the siblings.

Pedigree of ARPC1B-deficient patients. (A) Genetics and pedigree of families included in the study with reported mutations. Squares: male subjects; circles: female subjects; black filled symbols: patients with mutation; crossed-out symbols: deceased subjects. Each generation is designated by a roman numeral (I-II). No genomic DNA was available for testing for siblings labeled “E?”. (B) Nucleotide positions of mutations identified in index patients and representation of amino acid change caused by the mutations. (C) Crystal structure of the ARP2/3 complex from Bos taurus (access protein data bank: 1K8K), location of variants in the ARPC1B structure and modeling of c.64+1G>C splice donor and p.Val208Phe missense variants in P1 (blue) and P2 (red).

Pedigree of ARPC1B-deficient patients. (A) Genetics and pedigree of families included in the study with reported mutations. Squares: male subjects; circles: female subjects; black filled symbols: patients with mutation; crossed-out symbols: deceased subjects. Each generation is designated by a roman numeral (I-II). No genomic DNA was available for testing for siblings labeled “E?”. (B) Nucleotide positions of mutations identified in index patients and representation of amino acid change caused by the mutations. (C) Crystal structure of the ARP2/3 complex from Bos taurus (access protein data bank: 1K8K), location of variants in the ARPC1B structure and modeling of c.64+1G>C splice donor and p.Val208Phe missense variants in P1 (blue) and P2 (red).

Structural modeling for the c.64+1G>C and the c.64+1G>A spicing site mutations on the crystal structure of ARP2/3 complex30 showed an insertion of 7 additional hydrophobic amino acids at the loop between the first 2 β-strands in P1 and P6 (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 5), which might be exposed to the solvent interfering with protein folding and changing protein aggregation with other subunits, leading to novel protein-protein interactions. An unpaired cysteine on the edge of the loop might be subjected to oxidation, leading to nonspecific aggregation through the formation of a disulfide bridge. The p.Val208Phe mutation (P2) is located in the tightly packed hydrophobic core of the protein and could destabilize the ARPC1B structure, leading to an incorrect folding.

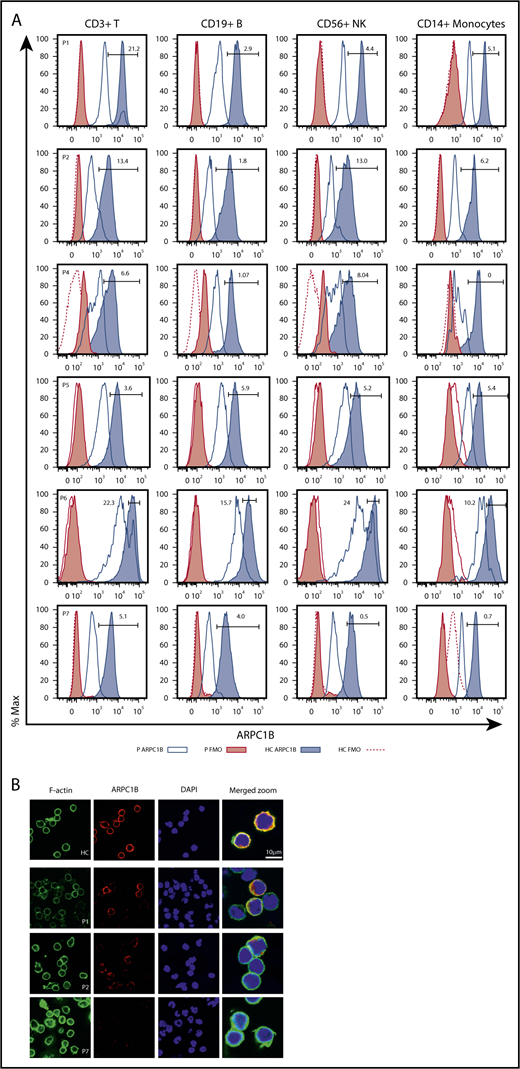

Altered expression of ARPC1B protein in PBMCs

We next carried out detailed immunological investigations in patients, according to availability of blood samples. We first set up an intracellular flow cytometry staining in PBMCs31 to investigate whether ARPC1B mutations in these patients affect protein expression. As shown in Figure 2, we observed severely reduced levels of ARPC1B in T, B, NK cells, and monocytes of ARPC1B-mutated patients as compared with pediatric healthy controls (HC) and to P7, completely ARPC1B negative. P1 had a subpopulation (21%) of T cells expressing normal levels of ARPC1B, which was clearly distinct from the ARPC1B-negative population. In P2, 13% of T and NK cells expressed low levels of ARPC1B. In P4 and P5, the ARPC1B expression was low in all subpopulations, whereas in P6 a subpopulation of T (22%) and NK (24%) cells express normal levels of ARPC1B. Fresh PBMCs from available patients and controls were stained for ARPC1B and F-actin, nuclei counterstained with DAPI, and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Figure 2B). In P1, a normal ARPC1B expression was found in ∼20% of leukocytes as compared with HC and P7, in which no detectable ARPC1B was found. In P2, some cells appear to express reduced levels of ARPC1B that accumulates in larges patches around the cell periphery and does not distribute evenly along the actin cortex.

Phenotypical characterization of ARPC1B-deficient patients. (A) Histograms showing ARPC1B expression in T, B, NK cells, and monocytes in patients included in the study (blue lines) and their healthy controls (HC; blue tinted lines) determined by flow cytometry. Red filled lines: negative controls of patients. Red dashed lines: negative controls of HC. Percentage of ARPC1B+ in patients’ cells is indicated. (B) Confocal microscopy of ARPC1B, F-actin, merged with nuclei (DAPI) in a representative field of HC, P1, P2, and P7 (ARPC1B-null patient) peripheral blood lymphocytes. Bar represents 10 μm. Arrows indicate positive staining for ARPC1B and F-actin.

Phenotypical characterization of ARPC1B-deficient patients. (A) Histograms showing ARPC1B expression in T, B, NK cells, and monocytes in patients included in the study (blue lines) and their healthy controls (HC; blue tinted lines) determined by flow cytometry. Red filled lines: negative controls of patients. Red dashed lines: negative controls of HC. Percentage of ARPC1B+ in patients’ cells is indicated. (B) Confocal microscopy of ARPC1B, F-actin, merged with nuclei (DAPI) in a representative field of HC, P1, P2, and P7 (ARPC1B-null patient) peripheral blood lymphocytes. Bar represents 10 μm. Arrows indicate positive staining for ARPC1B and F-actin.

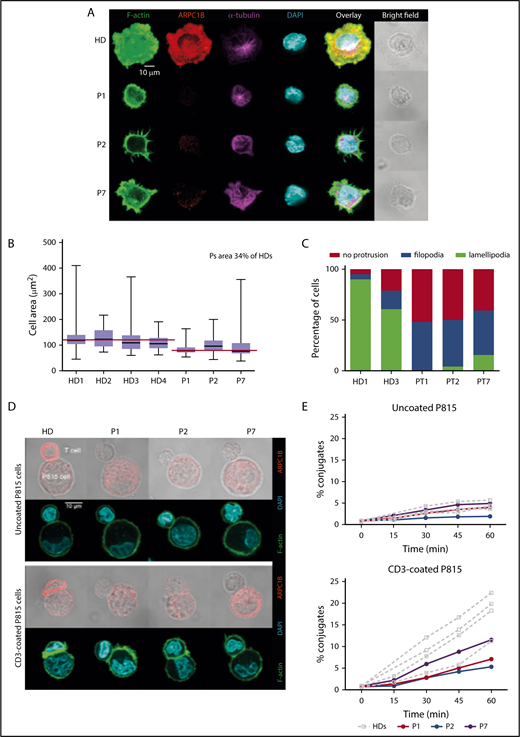

ARPC1B-deficient T cells emit aberrant filopodia and fail to spread radially

We therefore investigated whether ARPC1B mutations might affect the assembly or the structure of the IS. PHA T-cell blasts were deposited on stimulatory glass coverslips with adsorbed ICAM-1 and anti-CD3 Ab for IS assembly. In HC, the IS formation over ICAM-1/anti-CD3 involved a radial spreading, with distribution of F-actin into a wide peripheral lamellipodia that extended well beyond the cell body (Figure 3A). Upon IS assembly, ARPC1B polarized to the peripheral lamellipodia where it colocalized with F-actin. As expected, the microtubules converged toward the stimulatory surface in a rather central position of the synapse. In contrast, ARPC1B-deficient T cells in P1, P2, and P7 failed to spread radially. We observed a reduced surface over the stimulatory surface in ARPC1B-deficient T cells by image quantification, confirming the inability in assembling the IS (Figure 3B). Instead of disrupting the cortical actin to assemble a peripheral circular lamellipodia, ARPC1B-deficient T cells from the 3 studied patients emitted thin filopodia that stemmed from the cell cortex (Figure 3A,C). Interestingly, some T cells from P7 displayed a partial disruption of cortical actin with emission of erratic pseudopodia decorated with short filopodia. Whereas the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton was profoundly affected in the patient’s T cells, microtubules organization appeared normal (Figure 3A). These observations are in agreement with previous experiments in Jurkat T cells inhibited for Arp2 or Arp3 with short hairpin RNAs.32

Defective assembly of the IS in ARPC1B-deficient T lymphocytes. (A) Confocal images of T cells from a HC and P1, P2, and P7 adhering to ICAM1/anti-CD3 Ab-coated slides and stained for F-actin, ARPC1B, α-tubulin, and DAPI. Images representative from 1 out of 3 experiments. (B) Quantification of the area of individual cells interacting with ICAM1/anti-CD3 Ab. Median bar with minimum-maximum. Red lines: median average for HD and patients. %: Mean percentage of the medians between patients and HDs. Results of 2 independent experiments. (C) Distribution of T-cell morphologies according to the indicated subtypes: cell without protrusion, emission of filopodia, or assembly of a circular lamellipodia. (D) Representative confocal images of control T cells or T cells from P1, P2, and P7 upon interaction with P815 that have been precoated or not with anti-CD3 Ab. Fixed conjugates were stained for F-actin, ARPC1B, and DAPI. Representative images from 1 out of 2 experiments. (E) Quantification of the proportion of T cells engaged in conjugates with P815 targets precoated or not with anti-CD3 Ab. Conjugate formation was assessed at the indicated time points upon cell mixture. Results of 2 independent experiments.

Defective assembly of the IS in ARPC1B-deficient T lymphocytes. (A) Confocal images of T cells from a HC and P1, P2, and P7 adhering to ICAM1/anti-CD3 Ab-coated slides and stained for F-actin, ARPC1B, α-tubulin, and DAPI. Images representative from 1 out of 3 experiments. (B) Quantification of the area of individual cells interacting with ICAM1/anti-CD3 Ab. Median bar with minimum-maximum. Red lines: median average for HD and patients. %: Mean percentage of the medians between patients and HDs. Results of 2 independent experiments. (C) Distribution of T-cell morphologies according to the indicated subtypes: cell without protrusion, emission of filopodia, or assembly of a circular lamellipodia. (D) Representative confocal images of control T cells or T cells from P1, P2, and P7 upon interaction with P815 that have been precoated or not with anti-CD3 Ab. Fixed conjugates were stained for F-actin, ARPC1B, and DAPI. Representative images from 1 out of 2 experiments. (E) Quantification of the proportion of T cells engaged in conjugates with P815 targets precoated or not with anti-CD3 Ab. Conjugate formation was assessed at the indicated time points upon cell mixture. Results of 2 independent experiments.

Because Arp2/3 inhibition in Jurkat T cells results in the emission of formin-dependent actin spikes,33 we reasoned that the aberrant filamentous structures assembled at the periphery of ARPC1B-deficient T cells might arise from an imbalanced actin remodeling in favor of formins. To test this hypothesis, T cells were treated with the pan-formin inhibitor SMIFH2 prior to and during interaction with coverslips with absorbed ICAM-1/anti-CD3. We observed a collapse of the filopodia from the surface of patient-derived T cells (supplemental Figure 6A), indicating that the actin-rich filamentous structures emitted by patients’ T cells are under the control of formins. However, formin inhibition did not allow the ARPC1B-defective T cells to assemble a normal synapse, as indicated by lack of spreading (supplemental Figure 6B), confirming the driver role of the Arp2/3 complex in the formation of the IS.

ARPC1B-deficient T cells fail to assemble an IS

To further assess the consequence of ARPC1B deficiency in assembling the T-cell IS upon interaction with antigen-presenting cells, expanded T cells were incubated with anti-CD3-coated P815 cells and examined.34 Upon contact with uncoated P815 cells, control T cells established a narrow contact without major ARPC1B or F-actin enrichment. Upon interaction with anti-CD3-coated target cells, control T cells assembled an IS characterized by cell flattening and enlargement of the contact area, which accumulated polymerized actin (Figure 3D). In agreement with previous data (Figure 3A), ARPC1B polarized to the IS where it colocalized with F-actin. As compared with the control T cells, ARPC1B-deficient T cells displayed reduced spreading over the surface of the stimulatory P815 cells and very limited enrichment of F-actin at the site of contact (Figure 3D). Although filopodia were detected at the surface of patients’ T cells, these structures were less prominent than over ICAM-1/anti-CD3 Ab. The defective actin remodeling at the IS was associated with a reduced ability to stabilize contacts with the P815 cells. Indeed, the ARPC1B-deficient T cells displayed a reduced ability to form conjugates with the anti-CD3 Ab-coated P815 cells, as measured in parallel by flow cytometry (Figure 3E). Together, T cells from ARPC1B-deficient patients harbor a major defect in the organization of the IS, in agreement with the location of ARPC1B at the actin-rich synaptic lamellipodia in control cells.

Functional defects in lymphocytes of ARPC1B-mutated patients

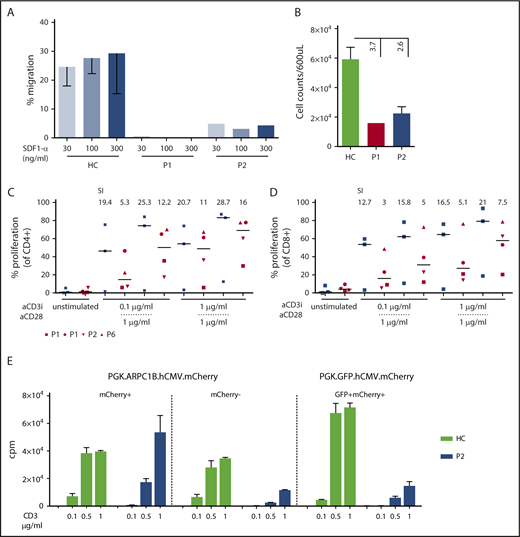

To dissect the role of ARPC1B in lymphocyte cytoskeleton remodeling, we tested freshly isolated PBMCs from P1 and P2 in an in vitro migration assay in response to SDF1-α (CXCL12)35 (Figure 4A). Lymphocytes from ARPC1B-mutated patients failed to migrate or responded poorly to increasing doses of SDF1-α. Moreover, spontaneous migration was 3.7- and 2.6-fold lower than the controls (Figure 4B).

Impaired migration and proliferation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. (A) Percentage of migrated freshly isolated lymphocytes after 3 hours of stimulation with increasing concentrations of SDF1-α in P1 and P2 as compared with HC (n = 6). Mean ± SEM. (B) Spontaneous migration in P1 (red bar), P2 (blue bar), and HC (n = 6; green bar). Mean ± SEM. (C-D) Percentage of proliferation determined by cell trace dilution in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for HC (blue, n = 3) and patients P1, P2, and P6 with anti-CD3 alone or in combination with anti-CD28. Median (bar) and patients’ symbols are indicated. Stimulation index: ratio between stimulated and unstimulated cells. (E) Restoration of proliferation in transduced PHA T-cell blasts of P2 and a HC. T cells were stimulated with increasing doses of plate-bound anti-CD3. Graph summarizes the proliferation of T cells sorted according to mCherry or GFP expression. Vectors used for transduction are indicated. Mean ± SEM. cpm, counts per minute.

Impaired migration and proliferation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. (A) Percentage of migrated freshly isolated lymphocytes after 3 hours of stimulation with increasing concentrations of SDF1-α in P1 and P2 as compared with HC (n = 6). Mean ± SEM. (B) Spontaneous migration in P1 (red bar), P2 (blue bar), and HC (n = 6; green bar). Mean ± SEM. (C-D) Percentage of proliferation determined by cell trace dilution in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for HC (blue, n = 3) and patients P1, P2, and P6 with anti-CD3 alone or in combination with anti-CD28. Median (bar) and patients’ symbols are indicated. Stimulation index: ratio between stimulated and unstimulated cells. (E) Restoration of proliferation in transduced PHA T-cell blasts of P2 and a HC. T cells were stimulated with increasing doses of plate-bound anti-CD3. Graph summarizes the proliferation of T cells sorted according to mCherry or GFP expression. Vectors used for transduction are indicated. Mean ± SEM. cpm, counts per minute.

To assess T-cell receptor (TCR)–driven proliferation, total PBMCs from available samples were stained with CellTrace dye and stimulated for 3 days in the presence of increasing doses of plate-bound anti-CD3 Ab. T-cell proliferation was reduced at lower concentrations of anti-CD3 Ab (0.1bμg/mL) but was normal at higher concentrations or after the addition of anti-CD28 Ab (Figure 4C-D). This might correlate with improved induction of actin rearrangement that is observed after TCR costimulation.36 To determine if the expression of a normal ARPC1B corrects the proliferation defect observed in patients’ cells, PHA T-cell blasts of P2 and a HC were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding either ARPC1B+ and mCherry or GFP and mCherry. The percentage of ARPC1B+mCherry+ T cells was 18% (supplemental Figure 7A). Bulk T-cell lines were sorted according to mCherry expression and stimulated for proliferation. Only the mCherry+ T cells expressed ARPC1B at higher levels (supplemental Figure 7B-C) and proliferated at similar levels than controls and mock-transduced sorted samples (Figure 4E).

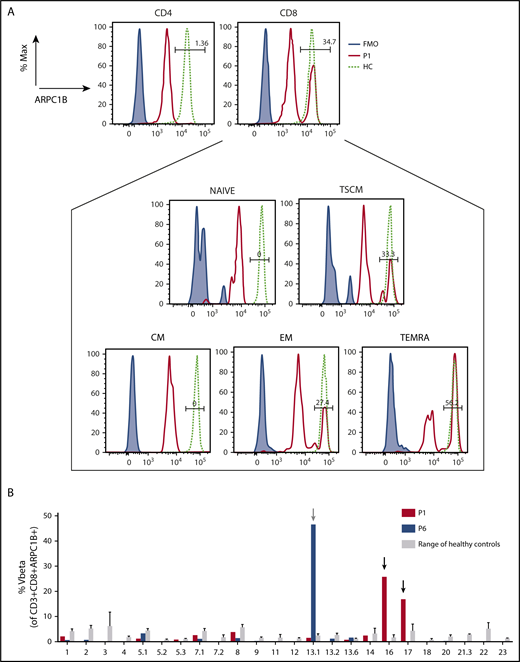

Altered T-cell repertoire and somatic reversion in CD8+ memory T cells

We next asked if an ARPC1B+ population in the T-cell compartment of P1 and P6 could be because of a somatic reversion as observed frequently in WASP-deficient patients.37-39 High throughput sequencing on whole blood revealed 3.17 ± 0.01374% of wild-type sequence in P1 and 1.96% ± 0.10684% in P6 (supplemental Table 4), and in both patients reversion of the variant could be observed. ARPC1B was expressed in CD8+ T cells (34.7% in P1 and 30.6% in P6, respectively), whereas it was absent in CD4+ T cells and B cells. In P6, 24% of NK cells were ARPC1B+. In P1, ARPC1B+ cells were present only in TEMRA (T effector memory-RA+ cell), effector memory (EM), and T memory stem cell (TSCM) compartments, but no ARPC1B+ cells were detected in naïve and central memory T cells (Figure 5A). TCR Vβ repertoire was polyclonal, with some skewing in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (supplemental Figure 8). Indeed, NGS of the immunoglobulin (IGH) and TCR-β (TRB) and TCR-γ (TRG) transcripts in circulating lymphocytes of P1 showed a significantly reduced Shannon’s index and high junctional diversity levels, measured by the germline index40 (supplemental Methods and supplemental Figure 9). We found 43% of P1 ARPC1B+CD8+cells that is mainly represented by 2 Vβ families (Vβ16 and Vβ17). Among 14% of ARPC1B+CD8+ T cells in P6, the Vβ13.1 was the main representative (Figure 5B).

Characterization of revertant CD8+T cells. (A) Histograms showing the presence of a revertant ARPC1B+ population in CD4+ and CD8+ compartments in freshly isolated PBMCs of P1 (red line) as compared with HC (dashed line). Blue line: negative control. Box represents the percentage of ARPC1B+ cells in naïve, central memory (CM), TSCM (CD3+CD8+CD45RA+CD62L+CD95+), EM (CD3+CD8+CD45RA−CD62L−), and TEMRA (CD3+CD8+CD45RA+CD62L−) gated on CD8+ T cells. P1, black line; HC, dashed line; negative control, blue line. (B) Determination of Vβ in gated CD3+CD8+ARPC1B+ T cells in P1 (red bars) and P6 (blue bars) as compared with HC (gray bars, n = 3). Mean ± SD. Arrows indicate relative expansion of Vβ.

Characterization of revertant CD8+T cells. (A) Histograms showing the presence of a revertant ARPC1B+ population in CD4+ and CD8+ compartments in freshly isolated PBMCs of P1 (red line) as compared with HC (dashed line). Blue line: negative control. Box represents the percentage of ARPC1B+ cells in naïve, central memory (CM), TSCM (CD3+CD8+CD45RA+CD62L+CD95+), EM (CD3+CD8+CD45RA−CD62L−), and TEMRA (CD3+CD8+CD45RA+CD62L−) gated on CD8+ T cells. P1, black line; HC, dashed line; negative control, blue line. (B) Determination of Vβ in gated CD3+CD8+ARPC1B+ T cells in P1 (red bars) and P6 (blue bars) as compared with HC (gray bars, n = 3). Mean ± SD. Arrows indicate relative expansion of Vβ.

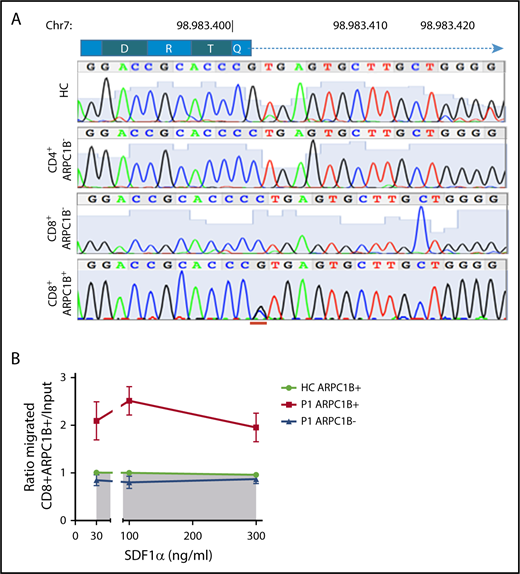

To determine if the revertant CD8+ T cells restore normal gene sequence, P1-derived PHA T-cell blasts were sorted according to CD4, CD8, and ARPC1B expression. Only ARPC1B+CD8+ T cells were heterozygous at the site of donor splice site mutation, as a consequence of a secondary spontaneous mutational event. In contrast, sorted ARPC1B-CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells were homozygous for the c.64+1G>C mutation (Figure 6A). Engraftment of maternal cells was excluded by HLA chimerism analysis (data not shown). We next tested if ARPC1B+ T cells behaved differently than ARPC1B− cells in a migration assay (Figure 6B). Unlike freshly isolated PBMCs, PHA T-cell blasts from P1 migrated to SDF1-α, although at lower levels of controls (data not shown). Interestingly, an enrichment for ARPC1B+CD8+ T cells in the migrating population was found, suggesting a preferential advantage for ARPC1B+ expressing cells.

Preferential migration of revertant CD8+T cells. (A) Electropherograms showing homozygous peaks in CD4+CD8−ARPC1B− and CD4−CD8+ARPC1B− and heterozygous peak in CD4−CD8+ARPC1B+ in sorted subpopulations in PHA T-cell lines of P1 as compared with bulk population in a HC. The site of second mutation is indicated in red. (B) Ratio of migrated ARPC1B+CD8+ (red) and ARPC1B−CD8+ (blue) T cells at to SDF1-α as compared with HC (n = 6, shaded area). Mean ± SEM. Input: percentage of T cells expressing ARPC1B before migration.

Preferential migration of revertant CD8+T cells. (A) Electropherograms showing homozygous peaks in CD4+CD8−ARPC1B− and CD4−CD8+ARPC1B− and heterozygous peak in CD4−CD8+ARPC1B+ in sorted subpopulations in PHA T-cell lines of P1 as compared with bulk population in a HC. The site of second mutation is indicated in red. (B) Ratio of migrated ARPC1B+CD8+ (red) and ARPC1B−CD8+ (blue) T cells at to SDF1-α as compared with HC (n = 6, shaded area). Mean ± SEM. Input: percentage of T cells expressing ARPC1B before migration.

Discussion

We report herein that ARPC1B is a key molecule driving cytoskeletal dynamics in human T cells. Biallelic mutations in the ARPC1B gene altering protein structure result in complete autosomal recessive ARPC1B deficiency characterized by CID and with impaired T-cell migration and proliferation. ARPC1B gene transfer restored protein expression and T-cell proliferation in vitro. The occurrence of reversion in CD8+ T cells in 2 patients led to in vivo selection of ARPC1B-expressing cells and preferential migration ability.

NGS was a fundamental tool to identify the causative mutations in ARPC1B gene12,16,17 in 6 newly described patients from 6 unrelated kindred with a variable phenotype ranging from a clinical picture clearly consistent with a Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS)15,41 to a predominant inflammatory picture dominated by severe flares of systemic inflammation and lymphoproliferation. Thrombocytopenia with low platelet volume, mild T-cell lymphopenia, vasculitis, and failure to thrive were common findings in all patients. To our knowledge, 6 other cases of complete autosomal recessive ARPC1B deficiency have been described12,16,17 and reported with variable degree of immune dysregulation. It is possible that several cases of ARPC1B deficiency exist that are still unrecognized or incorrectly diagnosed with WAS-like disease or CID, associated with platelet dysfunction, vasculitis, and systemic inflammation. Interestingly, all ARCP1B-mutated patients presented variably degrees of inflammation indicating the possible role of the ARP2/3 complex in the regulation or activation of the inflammatory response. In this regard, the impact of ARCP1B mutations on monocyte and macrophage subsets will shed light on the severe inflammatory phenotype observed in some patients, such as in P2.

Platelet abnormalities were reported in a single patient by Kuijpers et al16 describing mild bleeding tendency, a very mild platelet dysfunction and aggregation defect, a nearly normal PAC1 expression, and slight reduction of CD62P and CD63. Kahr et al12 found defects in platelets size and morphology in 3 ARPC1B-mutated patients, with reduction of calcium-rich platelets dense granules and inability to form lamellipodia, for a profound loss of actin branching. No defects were observed in this work for aggregation and platelets spreading. We documented bleeding in 3 patients, restricted to the gastrointestinal tract (bloody diarrhea, 2/3) or because of gingival bleeding (1/3). Patients reported here share some of the characteristic platelet abnormalities reported in WAS,41,42 including altered morphology, reduced dense granule content, and decreased surface expression of PAC1 especially after thrombin stimulation. Despite an increased activation of CD62P/PAC1 was reported in a cohort of WAS patients,43 we observed reduced levels of PAC1, similarly to patients with immune thrombocytopenia and high bleeding score.44

T-cell proliferation defects resemble what previously described in WAS and suggest that defects in cytoskeletal dynamics mediated by ARPC1B deficiency may cause impaired signaling through the TCR and costimulatory molecules.21,41,45 Indeed, revertant T cells observed in P1 displayed normal TCR-driven proliferation even at low-dose anti-CD3, sustaining the hypothesis of a selective advantage for revertant T cells in vivo. To our knowledge, no defects in B, NK, and monocytes were described so far. We observed a residual ARPC1B expression in NK cells. In WAS patients, NK cells were defective in cytotoxic function and F-actin content at the IS.46 Recently, Carisey et al47 showed that loss of the ARP2/3 complex related to impaired F-actin dynamism, as a critical component to secretory function needed for cytotoxicity. We cannot exclude that NK cells with residual expression of ARPC1B might be affected, and this function may be further studied, especially in P6 where a high percentage of revertant cells has been found.

We found that the ARPC1B mutations cause altered cellular morphology and aberrant filopodia and fail to spread radially with defective IS and conjugates formation. The inhibition of formins in favor of ARP2/3 activation and formation of filopodia results in their collapse in patients’ cells with decreased IS, which was also observed in controls, demonstrating a driver role of the ARP2/3 complex in the formation of this cellular structure. Together, our data demonstrate that ARPC1B-deficient T cells harbor a major defect in the organization of the IS, in agreement with the location of ARPC1B at the actin-rich synaptic lamellipodia in control cells. Defective chemokine-induced T-cell migration may be because of the impaired intracellular cytoskeletal machinery as the result of inability to activate the ARP2/3 complex. SDF1-α signaling involves the CDC42-WASP pathway to induce chemotaxis and activation of the ARP2/3 complex.3 Defects of T-cell activation and migration have been described in other conditions because of mutations in genes interacting with the ARP2/3 complex or involved in activation of this pathway. Indeed, in WAS patients defective chemotaxis was reported for T and B cells.3,48 In WIPF1-deficient mice and patients, an aberrant F-actin rearrangement leads to impaired activation of T cells.49,50 DOCK2-deficient cells showed defects in chemokine-induced lymphocyte migration, an impaired RAC1 activation, and defects in actin polymerization.2 The finding of somatic revertant in P1 and P6 CD8+ T cells and P6 NK cells is intriguing and suggests a strong selective pressure for the expansion of the revertant cells. Somatic revertant mosaicisms have been reported in other PID including WAS37-39 and can be because of true back mutations leading to restoration of wild-type sequences or to second site mutations resulting in compensatory changes. In WAS, somatic mosaicism has been reported in up to 11% of affected patients, especially in older patients, and is generally restricted to the T-cell subset.37,51 Memory T-cell and TSCM subsets constitute the majority of the T-cell pool in P1. TSCMs are a subpopulation with a high differentiation potential and self-renewal abilities and can rapidly generate antigen-experienced T-cell subsets with effector functions after stimulation.22 The presence of ARPC1B+ cells predominantly among EM, TEMRA, and TSCM subsets suggests that part of the selective pressure may have occurred upon antigen stimulation or as a result of homeostatic proliferation in the setting of T-cell lymphopenia. It is unclear whether ARPC1B deficiency may impact TCR diversity by impacting thymic maturation. Somech et al17 described a reduction of the TCR repertoire only in 1 patient, as a secondary consequence of altered selection during T-cell development, differential survival in the periphery, and/or altered immune responses caused by loss of ARPC1B function. Our patients showed a polyclonal repertoire, with some restriction of the TCR diversity and clonotypic expansion at immune phenotype and at NGS for TRB. Few ARPC1B+ clones survive in the periphery, sustaining the hypothesis that somatic reversion might have occurred in a lymphoid T-cell progenitor prior to TCR rearrangement or could be because of in vivo selection of ARPC1B+ clones after infectious events. Differently from RAG1/2 deficiency, where a poor TRB CDR3 diversity and an higher germline index are indicative of defective CDR3 junctional diversity,40 this was reduced in our patient, as indicative of higher junctional diversity level and most likely normal thymic maturation. The absence of detectable ARPC1B+ naïve T cells may suggest that the revertant T-cell progenitor was exhausted in vivo whereas memory T cells persisted long-term. Finally, transduction of patients’ T cells with a lentiviral vector encoding ARPC1B restored protein expression and normal proliferation, further corroborating the pathogenetic role of ARPC1B in these patients. These results open the way for gene therapy strategies for the treatment of this novel PID as in the treatment of other PID.21,52,53

In conclusion, our data expand the spectrum of clinical manifestation in ARPC1B deficiency and show that defects in ARPC1B are associated with altered cytoskeletal dynamics and functions in T cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Samantha Scaramuzza, Stefania Crippa, and Alessandra Mortellaro for fruitful scientific discussion; Lucia Sergi Sergi for help in vector production; Fanny Fouyssac (Nancy Hospital) for P6 referral; Christine Bole for genomic platform at Institute Imagine; and Maria Paola Rancoita from CUSSB (University Vita Salute, Milan) for statistical support.

The study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministero della Salute (Programma di rete, NET-2011-02350069), the European Commission (ERARE-3-JTC 2015 EUROCID), and Fondazione Telethon (TIGET Core grant C6). Part of this work was carried out in ALEMBIC, an advanced microscopy laboratory established by the San Raffaele Scientific Institute and the Vita-Salute San Raffaele University. This study was also partially funded by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health; and by the Colombian Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation Colciencias (111574455633, contract 774-2016).

Authorship

Contribution: I.B. designed and supervised the research, performed experiments, developed gene panel for targeted sequencing, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript; M.Z. performed bioinformatics analysis and molecular and functional experiments; M.P.C., F.B., S.V., M.G., G.R., R.C., P.P., J.L.F., T.I., A.I., A.B., J.A.A.-A., J.B., N.M., D.M., B.N., and R.S. provided clinical samples and patients’ clinical data; D.M. and M.B.-N. performed bioinformatic and genetic analysis for P6; Y.N.L. performed NGS for TRB, TRG, and IGH analysis; M.B.-N. performed high-throughput sequencing analysis; L. Pfajfer, C. Scielzo, L. Pavesi, and L.D. helped in cytoskeletal function assays and confocal microscopy; L.S. and A.V. performed platelet assays and analysis; S.G., C. Sartirana, F.D., S.S., P.C., A.L., J.R., A.A.A., J.A.A.-A., J.L.F., and L.B.-R. contributed to patient molecular and functional analyses and flow cytometry; B.M. performed HLA typing; J.-L.C., B.B., C.O.-Q., M.M.V., A.A.A., J.K., J.B., and K.D. performed genetic analysis; M.D. performed protein modelling; J.-L.C., L.D., and J.B. critically revised the manuscript; L.D.N., C. Scielzo, and M.G. participated in the study design, data interpretation, and manuscript revision; and A.A. designed and supervised the research, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Correspondence: Alessandro Aiuti, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy (SR-TIGET), Pediatric Immunohematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20123 Milano, Italy; e-mail: aiuti.alessandro@hsr.it.

REFERENCES

Author notes

M.G. and A.A. contributed equally to this study.