Abstract

We have identified a cell population expressing erythroid (TER-119) and megakaryocyte (4A5) markers in the bone marrow of normal mice. This population is present at high frequency in the marrows and in the spleens involved in the erythroid expansion that occurs in mice recovering from phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-induced hemolytic anemia. TER-119+/4A5+ cells were isolated from the spleen of PHZ-treated animals and were found to be blast-like benzidine-negative cells that generate erythroid and megakaryocytic cells within 24-48 hours of culture in the presence of erythropoietin (EPO) or thrombopoietin (TPO). TER-119+/4A5+ cells represent a late bipotent erythroid and megakaryocytic cell precursors that may exert an important role in the recovery from PHZ-induced anemia.

All the circulating elements of the blood derive from rare marrow cells through a complex process that involves extensive proliferation, lineage commitment, and cell differentiation and maturation.1,2 This process is modulated/regulated by cellular interactions with a wide range of cytokines.3,4One working model proposed for the mechanism of hematopoietic commitment suggests that the cells program their differentiation toward a particular lineage by progressive restriction of their differentiation potential.5 This model predicts the generation of bipotent cell precursors as one of the steps leading to erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation.6

The existence of this common precursor was suggested by the observations that the majority of the human7-10 and murine11,12 erythroleukemic and megakaryoblastic cell lines, as well as the blasts freshly isolated from human erythroblastic (M6) and megakaryoblastic (M7) leukemia,13,14 coexpress erythroid and megakaryocytic markers. These data could be explained either as lineage infidelity of leukemic cell differentiation15 or according to the hypothesis that leukemic cells retain certain properties of the normal cells from which they derive.5 Thus, in the case of these cell lines and primary leukemic blasts, they may have retained the properties of their common precursor.16

A linkage in the control of erythropoiesis and megakaryocytopoiesis was also suggested by the biological activity of erythropoietin (EPO) and thrombopoietin (TPO), the growth factors primarily responsible for differentiation toward these lineages.17,18 EPO and TPO were first identified because their levels specifically increase in the serum of animals recovering from anemia19 or thrombocytopenia,20 respectively. However, animals whose EPO17 (or TPO18) serum levels are exogenously increased develop not only increased numbers of circulating red cells (or platelets), but also higher numbers of megakaryocytic (or erythroid) progenitor cells in the marrow. Transgenic mice overexpressing the human TPO receptor (Mpl) exhibit not only chronic thrombocytosis but also enhanced erythroid recovery following 5-fluorouracyl treatment.21 Furthermore, the phenotype of mice that are genetically unable to express either one of these growth factors,22,23 as well as of their corresponding receptors,22,24,25 is characterized by reduced levels of both erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitor cells. Alternatively, because the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) and Mpl are coexpressed on erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitors26and erythroid progenitors from mice lacking EpoR differentiate in vitro in the presence of recombinant TPO,27 it is also possible that EPO and TPO are, at least partially, redundant in their control of the early stages of erythroid/megakaryocytic differentiation.

The hypothesis of a common cell precursor was invoked to explain the observation that not only the promoter regions of EpoR andMpl, but also those of all the other erythroid- and megakaryocytic-specific genes investigated, contain functional binding domains for a common panel of transcription factors.28Furthermore, mice in which the expression of eitherNef2,29,30Gata1,31,32 orFog6 (a recently described multitype zinc finger protein that modulates the biological activity of GATA)33 is impaired by gene disruption express a similar phenotype characterized by deficiency in both erythroid and megakaryocytic cell differentiation. Moreover, forced expression ofGata1 in avian myelomonocytic cells34 or in the murine myeloid cell line M135 induces both erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Evidence that megakaryocytic gene promoters are active into erythroid cells is provided by the observation that transgenic mice expressing a suicide gene under the control of the glycoprotein IIb (GpIIb)-specific promoter region are both thrombocytopenic and anemic.36 The fact that these mice contain reduced levels of multipotential progenitor cells supports the concept that activation of lineage-specific promoters precedes the establishment of the full differentiation program.37 38

Despite this accumulating data, common erythroid and megakaryocytic cell precursors have not been identified. Little evidence has been provided for a cell precursor whose frequency specifically increases in vivo by either increasing the serum levels of EPO39 or TPO40 or by forcing murine stem cells to expressMpl constitutively.41 Moreover, no cell precursor has been found to specifically decrease in tissues fromEpo/EpoR-22 orTpo/Mpl-42,43 deficient mice. Human44 and murine45 bipotent progenitor cells have been recently described but have not yet been isolated.

The specific aim of this study was to identify and describe the properties of an in vivo candidate cell for the bipotent precursor.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL mice (2-4 months old) were purchased as needed from Charles River (Calco, Italy). In experimental mice, phenylhydrazine (PHZ; 60 mg/kg body weight; Sigma Chem, St. Louis, MO) was injected intraperitoneally for 2 consecutive days.46 47On each of the 3 days after the second PHZ injection, 5 mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and the bones and spleens removed under sterile conditions for further analysis. All the procedures were approved by the institutional animal care committee.

Phenotypic analysis of the cells

Cell morphology was analyzed according to standard criteria on cytocentrifuged (Shandon, Astmoor, UK) slides stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa. Hemoglobin-containing cells were identified by benzidine staining.48 Megakaryocytes were identified by copper-thiocoline acethylcolinesterase E (ACHE) staining.49Cell viability was assessed either by trypan-blue (in optical microscopy) or by propidium iodide (5 μg/mL, Sigma) (in flow cytometry) exclusion. The cells were immunophenotyped with the following antibodies: phycoerythrin conjugated (PE)-TER-119 [Ly-76, a rat immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b) monoclonal antibody recognizing an antigen expressed on erythroid cells from erythroblasts to erythrocyte 50; fluorescein conjugated (FITC)-CD4, FITC-CD8, FITC-B220 (all from PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and FITC-4A5 [a rat monoclonal IgG2a antibody specific for murine megakaryocytes and platelets (gift from Dr S Burstein)51 that recognizes glycoprotein V (Burstein S, personal communication, April 1999)]. Cells, suspended in Ca++-, Mg++-free phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1% (v/v) bovine serum albumin, 2 mmol/L EDTA (that minimizes the adhesion of platelets, or of their membranes, to the cell surface), and 0.1% NaN3, were labeled with each antibody (∼1 μg/106 cells) for 30 minutes on ice. The cell fluorescence was analyzed either with the FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) or with a Coulter Epics Elite ESP (Coulter, Miami, FL) cell sorter. Cells incubated with appropriately labeled isotype controls (PharMingen) were used to gate the nonspecific fluorescence signal. Before the analysis, mature red cells were depleted by hypotonic lysis (0.38% ammonium chloride for 15 minutes on ice).

Cell purification

Monocellular spleen suspensions were prepared by cutting the spleens into small fragments in 5 mL of Ca++- and Mg++-free PBS containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and by passing the cell suspension through progressively smaller needles. Marrow cells were flushed from the femurs with a syringe containing 2 mL PBS-10% FBS. Marrow and spleen light density mononuclear cells were isolated by centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque (ρ = 1.077 g/mL; Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) at 800g for 20 minutes at room temperature. Light density spleen cells were either analyzed as such or further enriched for erythroid/megakaryocytic precursors by immunomagnetic selection or cell sorting. For the former, adherent cells were first removed by 2 cycles of adherence to plastic at 37°C for 1 hour. The nonadherent fraction was then depleted of B and T lymphocytes by binding to Dynabeads (Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) magnetic microspheres coated with anti-B220 (Pan-B) and anti-Thy 1.2 (Pan-T) antibodies as described by the manufacturer. The not-bound cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated 4A5 (∼1 μg/106 cells) for 30 minutes on ice, washed twice with PBS containing 0.5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and 2 mmol/L EDTA, and finally suspended in 80 μL of buffer and 20 μL of MACS microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) conjugated with goat antirat IgG F(ab)2. The cells were washed twice and loaded on a MS+/RS+ column placed in a MACS separator. 4A5− were recovered in the effluent fraction, whereas the 4A5+ cells were flushed out of the column. Both fractions were then incubated with PE-TER-119 for fluorimetric analysis. For cell sorter separation, light density cells were incubated with FITC-4A5 and 4A5+ cells sorted with a Coulter tuned at 488 nm. The sorted cells were then incubated with both PE-TER-119 and FITC-4A5 and double-positive cells sorted again. The sorted fractions were then reanalyzed for purity with the cytometer. In some experiments, purified cells were labeled again with FITC-4A5 and PE-TER-119 and examined under a fluorescent microscope (Axiookop Zeiss, GmbH, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence emission was captured and analyzed with the CytoVision program (Applied Imaging, Santa Clara, CA) after nucleous counterstaining with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vysis, Downers Grove, IL).

Liquid culture of spleen cells from PHZ-treated animals

Light density and purified cells (TER-119+/4A5± cells) were obtained from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice at days 1-2 following treatment. These cells were resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 10% Nutridoma (2-5 × 105 cells/mL) and incubated for up to 48 hours either without growth factors (GF) or in the presence of EPO (5 U/mL) or TPO (100 ng/mL) at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Semisolid culture of normal progenitor cells

Light density marrow cells (0.25-1.0 × 105cells/plate) isolated from normal mice were seeded into FBS-free semisolid culture plates (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). Colony growth was stimulated with the following combinations of recombinant growth factors: (i) rat stem cell factor (100 ng/mL), mouse interleukin 3 (IL-3; 10 ng/mL) (both from Sigma) and either human EPO (2 U/mL; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for burst-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E) growth52or (ii) mouse granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (50 ng/mL each; both from Sigma) for colony-forming unit–granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM) growth52 or (iii) human TPO (50 ng/mL; PrepoTech, London, UK) for colony-forming unit–megakaryocyte (CFU-Mk) growth.53 The growth of CFU-E–derived colonies was stimulated with EPO alone (2 U/mL).54 The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 in air and scored either 3 days (for CFU-E–derived colonies) or 7 days (for CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-Mk–derived colonies) following initiation of culture. Morphologically recognizable colonies that were clearly separated from the others (ie, the average distance from adjacent colonies was at least twice their diameter) were individually collected under sterile conditions, washed once in PBS, and suspended in 0.5 mL of Trizol (GIBCO BRL, Paisley, UK). In some experiments, single BFU-E– and CFU-GM–derived colonies were harvested at day 5 of culture and replated in secondary serum-deprived cultures stimulated with either EPO (5 U/mL) or TPO (100 ng/mL) alone (1 colony × 200 μL/well). After 4 days of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the wells were scored for the presence of CFU-E–derived colonies and megakaryocytes.

The frequency of BFU-E and CFU-E in the spleen of anemic mice and in the purified cell fractions was determined in triplicate cultures (105 or 104 cells/plate, respectively) under the conditions described above. To improve accuracy, the frequency of CFU-Mk was determined in triplicate semisolid agar cultures (0.3% Bacto-agar, 2.5 × 105 light density and 1.0 × 104 purified cells/plate) containingl-glutamine (2 mmol/L), l-serine (8 mg/L), sodium pyruvate (1 mmol/L), l-asparagine (16 mg/L), FBS (15% v/v); murine IL-3 (10 ng/mL), murine interleukin 6 (IL-6, 100 ng/mL; Sigma), and human TPO (50 ng/mL) in McCoy's 5A medium (GIBCO BRL). After 7 days of incubation, the agar was dehydrated and megakaryocytic colonies identified in situ by ACHE staining.53

RNA isolation and semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared using a commercial guanidine thiocyanate/phenol method (Trizol, GIBCO BRL) as described by the manufacturer. Glycogen (20 μg; Boehringer Mannheim) was added to each sample as a carrier. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed at 42°C for 30 minutes in 20 μL of 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, containing 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 U RNAse inhibitor, 2.5 U Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus reverse-transcriptase, and 2.5 μmol/L random hexamers (all from Perkin-Elmer, New Jersey). The expression ofα- and β-globin, EPO receptor (EpoR), acetylcholine esterase (AchE), GpIIb, TPO receptor (Mpl), and myeloperoxidase (Mpo) was analyzed by amplifying reverse-transcribed complementary DNA (cDNA; 2.5 μL) in the presence of the specific sense and antisense primers (100 nmol/L each) described elsewhere.55,56 The reaction was performed in 100 μL of 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, containing MgCl2(2 mmol/L), dNTP (200 μmol/L each), 0.1 μCi of [α32P]dCTP (specific activity 3000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Italia, Cologno Monzese, Italy) and 2 U AmpliTaq DNA polymerase. Primers specific for β-actin (50 nmol/L each) were added to each amplification after the first 10 cycles as a control for the amount of cDNA used in the reaction.55,56 PCR conditions were as follows: 60 seconds at 95°C, 60 seconds at 60°C, and 60 seconds at 72°C, using a GeneAmp 2400 Perkin-Elmer thermocycler. All the RT-PCR presented were done in the linear range of amplification defined by preliminary experiments to be, for most of the genes analyzed, between 20-30 cycles with the exception of Mpl (30-38 cycles) and α- and β-globin (18-24 cycles). Positive (RNA from adult marrow) and negative (mock cDNA) controls were included in each experiment. Aliquots (20 μL) were removed from the PCR mixture after amplification, and the amplified bands separated by electrophoresis on 4% polyacrylamide gel. Gels were dried using a Bio-Rad apparatus (Hercules, CA) and exposed to Hyperfilm-MP (Amersham Italia) for 2 hours at −70°C. All the procedures were according to standard protocols.57

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA test) using Origin 3.5 software for Windows (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA).

Results

Expression of erythroid and megakaryocytic markers in the marrow and spleens of normal and PHZ-treated mice

PHZ-treated mice develop a profound anemia from which they recover by augmenting splenic erythropoiesis (Tables1 and 2). Spleens from PHZ-treated animals are 1.8- to 3.7-fold larger than normal spleens. On day 1, they contained high numbers of BFU-E (140 ± 50 colonies/104 cells), relatively low numbers of CFU-E (21 ± 11 colonies/104 cells), and many (83% ± 5%) benzidine-negative blasts (Table 1). On day 3, they contained fewer BFU-E (15 ± 5 colonies/104 cells), more CFU-E (273 ± 39 colonies/104 cells), and even greater numbers (69% ± 15%) of benzidine-positive erythroblasts distributed along all maturation stages (Table 1). The numbers of megakaryocytic progenitors (0.8 ± 0.05 CFU-Mk/104cells, Table 1) and ACHE-positive cells (below detection limits) in the spleen remained low throughout the phase of recovery from anemia.

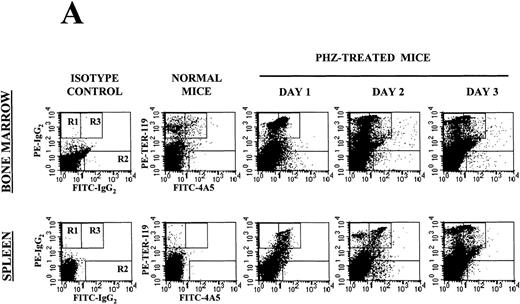

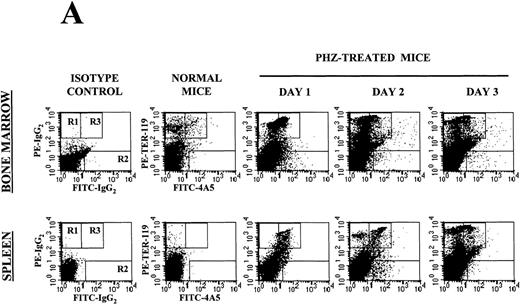

Flow cytometry analysis of the expression of erythroid (TER-119) and megakaryocytic (4A5) markers on cells from the bone marrow and the spleen of normal and PHZ-treated mice is shown in Figure1A and 1B. The frequency of TER-119+ and 4A5+ cells increased both in the marrow and in the spleen during the recovery from PHZ-induced anemia (Figure 1A, 1B, and Table 2). In addition, a third cell population coexpressing TER-119 and 4A5 was identified in the bone marrow of normal mice (Figure 1A). TER-119+/4A5+ cells represented 1.3% ± 0.6% of normal bone marrow cells and their frequency increased up to 3.8% (P < .01) in the marrow of PHZ-treated animals (Figure 1A and Table 2). A significant proportion (1.3%-8.3%) of TER-119+/4A5+ cells were also detected in the light density spleen cells from PHZ-treated mice. The analysis of the erythroid and megakaryocytic markers expressed by marrow and spleen cells from PHZ-treated animals was verified by examining the binding of both TER-119 and 2D5, an antibody that recognizes GPIIB (Burstein S, personal communication, April 1999). Dual positive TER-119+/2D5+ cells were identified in normal marrow and in the marrow and spleens from PHZ-treated mice. Their frequency was found to be identical to the frequency of TER-119+/4A5+ cells (Table 2 and result not shown).

Expression of erythroid and megakaryocytic markers in hematopoietic tissues from normal and phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated mice.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 (Y axes) and 4A5 (X axes) by bone marrow (top panels) and spleen (bottom panels) light density cells from normal and PHZ-treated (1, 2, and 3 days after the second injection) mice. The cells were also incubated with isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies as negative controls and the results presented on the left panels. R1, R2, and R3 indicate the gates used to define cells expressing TER-119 and 4A5 alone or coexpressing the 2 antigens. (The corresponding cell frequencies as determined in multiple experiments are presented in Table 2.) Propidium iodide–positive cells were less than 1% and were excluded by appropriate gating. (B) Hystogram analysis of the staining with FITC-IgG2 (right) or with FITC-4A5 (left) of normal (black line) and PHZ-treated (day 1, gray line) light density spleen cells gated in the TER-119–positive (R1+R3 of Figure 1A) area. (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid (β-globin and EpoR), megakaryocytic (GpIIb,AchE, and Mpl) and myeloid (Mpo) genes in spleen cells obtained from either normal or PHZ-treated (days 1 and 3) mice. Actin was amplified to control for the amount of cDNA used in each reaction. β-globin and actin were amplified for 18, 21, and 24 cycles; Mpl for 25, 30, and 35 cycles; and all the other genes for 27, 30, and 33 cycles (increasing numbers of cycles are indicated by a triangle on the top of the panels). The results are representative of those obtained in 3 separate experiments.

Expression of erythroid and megakaryocytic markers in hematopoietic tissues from normal and phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated mice.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 (Y axes) and 4A5 (X axes) by bone marrow (top panels) and spleen (bottom panels) light density cells from normal and PHZ-treated (1, 2, and 3 days after the second injection) mice. The cells were also incubated with isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies as negative controls and the results presented on the left panels. R1, R2, and R3 indicate the gates used to define cells expressing TER-119 and 4A5 alone or coexpressing the 2 antigens. (The corresponding cell frequencies as determined in multiple experiments are presented in Table 2.) Propidium iodide–positive cells were less than 1% and were excluded by appropriate gating. (B) Hystogram analysis of the staining with FITC-IgG2 (right) or with FITC-4A5 (left) of normal (black line) and PHZ-treated (day 1, gray line) light density spleen cells gated in the TER-119–positive (R1+R3 of Figure 1A) area. (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid (β-globin and EpoR), megakaryocytic (GpIIb,AchE, and Mpl) and myeloid (Mpo) genes in spleen cells obtained from either normal or PHZ-treated (days 1 and 3) mice. Actin was amplified to control for the amount of cDNA used in each reaction. β-globin and actin were amplified for 18, 21, and 24 cycles; Mpl for 25, 30, and 35 cycles; and all the other genes for 27, 30, and 33 cycles (increasing numbers of cycles are indicated by a triangle on the top of the panels). The results are representative of those obtained in 3 separate experiments.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression of erythroid- and megakaryocytic-specific genes from the spleens of normal and PHZ-treated mice is presented in Figure 1C. Of the genes analyzed, onlyβ-globin was readily amplified from normal spleen cells.AchE was amplified from those cells only after 33 cycles. In contrast, as predicted by the flow cytometry data, not only erythroid (β-globin and EpoR) but also megakaryocytic (GpIIb, AchE, and Mpl) genes were amplified with high efficiency from day 1 PHZ-spleens. With progression of the anemia (day 3 following PHZ-treatment), erythroid-specific genes (β-globin and EpoR) were amplified even more efficiently (maximal amplification noted after 18 and 30 cycles, respectively), whereas amplification of megakaryocytic genes was either barely (GpIIb) or not (AchE and Mpl) detectable. Mpo was never amplified, even at high numbers of cycles, from the spleens of either normal or PHZ-treated mice.

Isolation and characterization of TER-119+/4A5+ cells from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice

TER-119+/4A5+ cells were purified from the spleen of day 1-2 PHZ-treated animals because of the high TER-119+/4A5+ cell content of this tissue [∼1-1.75 × 106TER-119+/4A5+ cells/spleen = 5% of 40-70 × 106 light density cells/2 PHZ-treated spleens (Table 3)].

The first purification method was discovered serendipitously. We had found that day 1 PHZ-treated cells cultured for 18 hours in the absence of GF are enriched for cells that do not express β-globin by RT-PCR unless incubated for 2 hours with EPO.55 When analyzed for surface antigen expression, the GF-starved cells were found to contain few TER-119+ cells (7%) and to be enriched (∼5 times, from 5.8% to 30%) for TER-119+/4A5+ cells (Table 3). The majority (60%) of them were TER-119−/4A5− cells expressing either B220 (B cells) or CD4/CD8 (T cells) (Table 3). GF-starved cells contained some BFU-E (5 ± 2 BFU-E/104 cells) and no benzidine-positive (Table 1) or ACHE-positive (data not shown) cells.

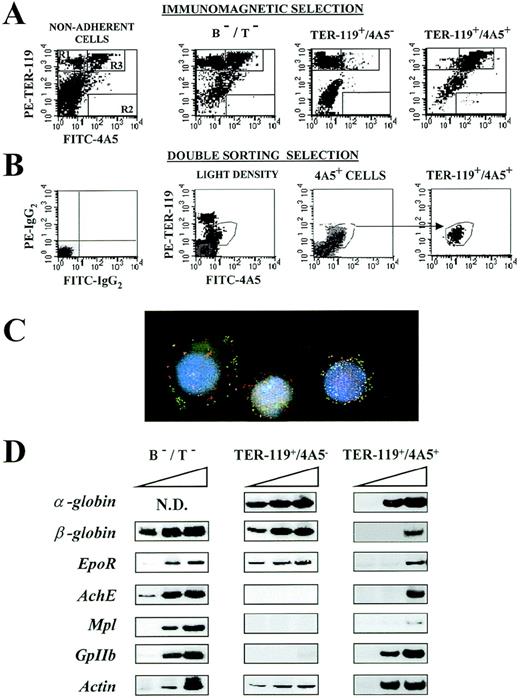

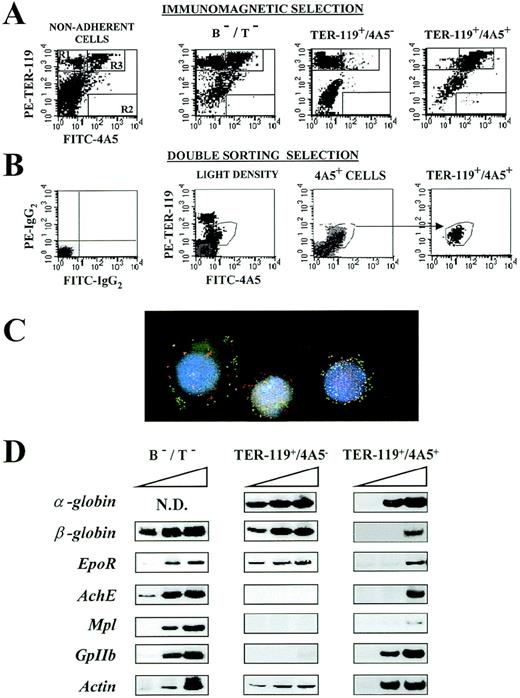

The physical isolation of TER-119+/4A5+ cells is described in Figure 2 and Table 3. For immunomagnetic selection, day 1-2 PHZ-treated light density spleen cells were first depleted of monocytes by 2 cycles of adherence to plastic, then depleted of lymphocytes by panning on panT/panB-coated microspheres (B−/T− cells), and finally positively selected for 4A5+ cells by the 4A5-coated immunomagnetic beads. The cell fraction that did not bind to the beads (4A5−) was isolated as a negative control. Alternatively, TER-119+/4A5+ cells were isolated from light-density spleen cells by 2 consecutive sortings, the first 1 on cells labeled with 4A5 only. The 4A5+ cells were then labeled with both 4A5 and TER-119 and sorted again.

Isolation of TER-119+/4A5+cells from the spleens of phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated animals.

(A) Immunomagnetic isolation. Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 (Y axes) and 4A5 (X axes) in nonadherent, B- and T-depleted (B−/T−), TER-119+/4A5−, and TER-119+/4A5+ cell fractions purified from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice. The gates, which identify cells expressing TER-119 and 4A5 alone or coexpressing the 2 antigens, were set to include only propidium iodide–negative cells. Gating and negative controls (not shown) are as in Figure 1A. Similar results were obtained in 7 additional purifications. The corresponding cell frequencies are summarized in Table 3. (B) Cell sorter isolation. Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 (Y axes) and 4A5 (X axes) in light density spleen cells, in 4A5+ cells isolated during the first sorting, and in the double TER-119+/4A5+ cells isolated with the second sorting. The gates, which identify cells expressing TER-119 and 4A5 alone or coexpressing the 2 antigens, were set to include only propidium iodide–negative cells. Gating and negative controls (not shown) are as in Figure 1A. Similar results were obtained in 3 additional purifications. The corresponding cell frequencies are summarized in Table 3. (C) Analysis of immunomagnetically purified TER119+/4A5+ cells using fluorescence microscopy and image analysis. Nuclei were counterstained (blue) with DAPI. FITC-4A5 fluorescence (green) and PE-TER-119 fluorescence (red) were individually analyzed and captured (original magnification ×100). (D) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid (α- and β-globin and EpoR) and megakaryocytic (AchE, Mpl, and GpIIb) genes in B−/T− cells or in TER-119+/4A5− and TER-119+/4A5+ cells (purified by double sorting) from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice. Actincomplementary DNA (cDNA) was amplified as well as control of the total cDNA used in each reaction. α-globin, GpIIb, andactin were amplified for 20, 25, and 30 cycles, whereas all the other genes were amplified for 25, 30, and 35 cycles (increasing numbers of cycles are indicated by a triangle on top of the panels). Similar results were obtained in 3 separate experiments.

Isolation of TER-119+/4A5+cells from the spleens of phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated animals.

(A) Immunomagnetic isolation. Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 (Y axes) and 4A5 (X axes) in nonadherent, B- and T-depleted (B−/T−), TER-119+/4A5−, and TER-119+/4A5+ cell fractions purified from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice. The gates, which identify cells expressing TER-119 and 4A5 alone or coexpressing the 2 antigens, were set to include only propidium iodide–negative cells. Gating and negative controls (not shown) are as in Figure 1A. Similar results were obtained in 7 additional purifications. The corresponding cell frequencies are summarized in Table 3. (B) Cell sorter isolation. Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 (Y axes) and 4A5 (X axes) in light density spleen cells, in 4A5+ cells isolated during the first sorting, and in the double TER-119+/4A5+ cells isolated with the second sorting. The gates, which identify cells expressing TER-119 and 4A5 alone or coexpressing the 2 antigens, were set to include only propidium iodide–negative cells. Gating and negative controls (not shown) are as in Figure 1A. Similar results were obtained in 3 additional purifications. The corresponding cell frequencies are summarized in Table 3. (C) Analysis of immunomagnetically purified TER119+/4A5+ cells using fluorescence microscopy and image analysis. Nuclei were counterstained (blue) with DAPI. FITC-4A5 fluorescence (green) and PE-TER-119 fluorescence (red) were individually analyzed and captured (original magnification ×100). (D) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid (α- and β-globin and EpoR) and megakaryocytic (AchE, Mpl, and GpIIb) genes in B−/T− cells or in TER-119+/4A5− and TER-119+/4A5+ cells (purified by double sorting) from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice. Actincomplementary DNA (cDNA) was amplified as well as control of the total cDNA used in each reaction. α-globin, GpIIb, andactin were amplified for 20, 25, and 30 cycles, whereas all the other genes were amplified for 25, 30, and 35 cycles (increasing numbers of cycles are indicated by a triangle on top of the panels). Similar results were obtained in 3 separate experiments.

With immunomagnetic selection, a total of [∼2 × 106 cells (∼66% of which TER-119+/4A5+ on reanalysis) were obtainedper 75 × 106 original light density spleen cells (Figure 2A and Table 3). Because the theoretical TER-119+/4A5+ cell content of the starting population was 4.3 × 106 cells, ∼32% of all the TER-119+/4A5+ cells were recovered with this procedure. The major contaminants were found to be single TER-119+ cells (10%-15%) and B and T lymphocytes (11%-15%; Table3). A lower number of cells (∼2 × 105) were recovered at the end of the purification by sorting. However, in this case, the purified cells contained a higher proportion of TER-119+/4A5+ (∼82% on reanalysis) cells, and the majority of contaminants were represented by neutrophils (the lymphocytes were excluded by size gating).

All the purified TER-119+/4A5+ cell fractions (irrespective of the method used) were enriched for benzidine- and ACHE-negative cells (Table 1 and 4) with the morphology of blasts (Figure 3B) that coexpressed fluorescein and phycoerythrin membrane-associated fluorescence by microscopic analysis (Figure 2C). Progenitor cells were not detected among the TER-119+/4A5+ cells (Table 1). In contrast, the TER-119+ cell fractions, isolated as control, contained benzidine-positive erythroblasts and some CFU-E (3 ± 2 CFU-E/104 cells) (Table 1).

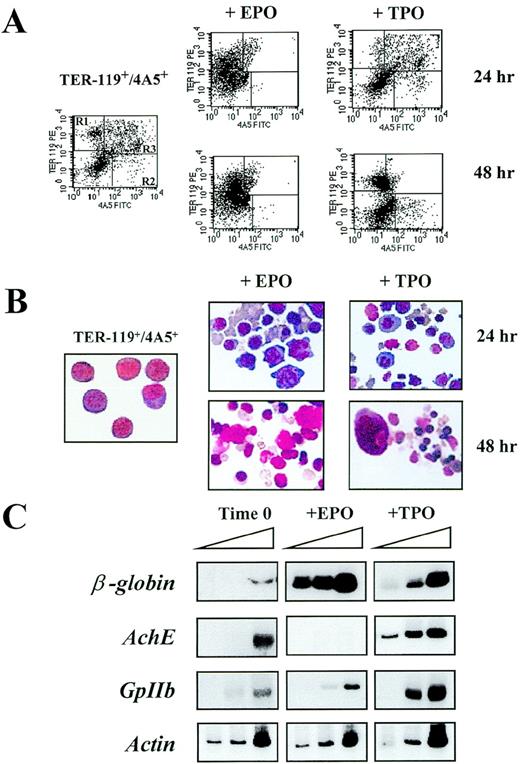

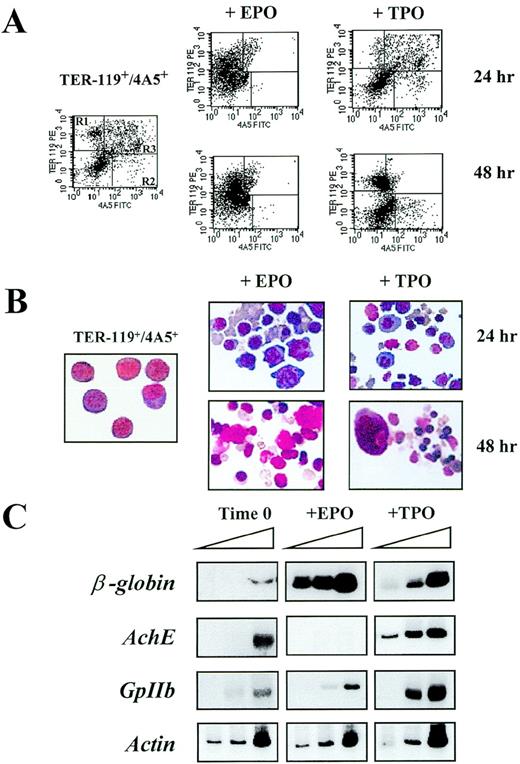

Differentiation of TER-119+/4A5+ cells isolated from the spleens of phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated mice in serum-deprived cultures stimulated with either erythropoietin (EPO; 5 U/mL) or thrombopoietin (TPO; 100 ng/mL).

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 and 4A5 in cells isolated by immunomagnetic selection as such (left panel) and after 24-48 hours of culture in the presence of either EPO (center panels) or TPO (right panels). Negative controls (not shown), analysis conditions, and cell gating are the same as in Figure 1A. The frequencies of the cells expressing TER-119 and/or 4A5 observed in individual experiments are shown in Table 4. (B) May-Grunwald Giemsa staining of Ter119+/4A5+ cells purified from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice as such (left panel) or cultured for 24-48 hours in the presence of either EPO (center panels) or TPO (right panels). The same cell preparations presented in Figure 2A (magnification ×400). (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid (β-globin) and megakaryocytic (AchE and GpIIb) genes in TER-119+/4A5+ cells purified from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice at baseline (left) or cultured for 24 hours in the presence of EPO (center) or TPO (right). Actin complementary DNA (cDNA) was amplified to control for the total amount of cDNA used in each reaction. The same cell fractions are shown in the top right panels of Figure 3A. β-globin and actin were amplified for 18, 21, and 24 cycles and AchE and GpIIb for 27, 30, and 33 cycles (increasing numbers of cycles are indicated by a triangle on top of the panels). Similar results were obtained in 3 additional experiments.

Differentiation of TER-119+/4A5+ cells isolated from the spleens of phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated mice in serum-deprived cultures stimulated with either erythropoietin (EPO; 5 U/mL) or thrombopoietin (TPO; 100 ng/mL).

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of TER-119 and 4A5 in cells isolated by immunomagnetic selection as such (left panel) and after 24-48 hours of culture in the presence of either EPO (center panels) or TPO (right panels). Negative controls (not shown), analysis conditions, and cell gating are the same as in Figure 1A. The frequencies of the cells expressing TER-119 and/or 4A5 observed in individual experiments are shown in Table 4. (B) May-Grunwald Giemsa staining of Ter119+/4A5+ cells purified from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice as such (left panel) or cultured for 24-48 hours in the presence of either EPO (center panels) or TPO (right panels). The same cell preparations presented in Figure 2A (magnification ×400). (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid (β-globin) and megakaryocytic (AchE and GpIIb) genes in TER-119+/4A5+ cells purified from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice at baseline (left) or cultured for 24 hours in the presence of EPO (center) or TPO (right). Actin complementary DNA (cDNA) was amplified to control for the total amount of cDNA used in each reaction. The same cell fractions are shown in the top right panels of Figure 3A. β-globin and actin were amplified for 18, 21, and 24 cycles and AchE and GpIIb for 27, 30, and 33 cycles (increasing numbers of cycles are indicated by a triangle on top of the panels). Similar results were obtained in 3 additional experiments.

The semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis for the expression of erythroid and megakaryocytic genes in the purified cell fractions is presented in Figures 2D and 3C. Both erythroid and megakaryocytic genes were readily amplified from the fraction depleted of B and T lymphocytes (B−/T− cells) (Figure 2D), whereas, as expected on the basis of their morphology, only the erythroid genes were amplified from fractions enriched for TER-119+ cells (Figure 2D). All of the genes analyzed were amplified also from TER-119+/4A5+ cells. However in this case,EpoR and Mpl, as well as α-globin andGpIIb, were amplified with high efficiency, but amplification of β-globin and AchE was detectable only after the highest number of PCR cycles (Figure 2C).

To verify if the purified TER-119+/4A5+ cells had the potential to differentiate into erythroid and megakaryocytic cells, they were cultured for up to 48 hours in the presence of EPO or TPO under serum-deprived culture conditions (Table4 and 5). TER-119+/4A5+ cells survived poorly in the absence of GF, and very few (20%-30%) of the original dual-labeled cells remained detectable after 48 hours of culture under those conditions. In cultures stimulated with either EPO or TPO, the total number of cells remained constant for 24 hours (Table5), and ∼50% of the original cell number was still detectable after 48 hours (Table 4 and 5). In contrast, the frequency of TER119+/4A5+ cells declined progressively and only 7%-10% of the cells expressed both antigens by 48 hours (Figure 3A and Table 5). The decline in the frequency of double-positive cells was paralleled by an increase in the frequency of cells positive for 1 antigen. In cultures stimulated with EPO, there was a significant increase in the number of single TER119+cells (60% by 24 hours), whereas, in cultures stimulated with TPO, the frequency of both TER-119+ (60% by 48 hours) and 4A5+ (16% by 24 hours) cells was significantly increased (Table 5). These surface phenotypic changes were accompanied by morphological changes: cells cultured with EPO became benzidine+ and acquired a predominantly erythroid morphology (Figure 3B). Orthochromatic erythroblasts, conceivably in the enucleation phase, were clearly recognized at 48 hours. Following culture with TPO, both erythroblasts and megakaryocytes were recognized (Figure 3B).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the genes expressed by the cultured TER-119+/4A5+ cells is presented in Figure 3C. The expression of all the genes analyzed increased when TER-119+/4A5+ cells were cultured for 48 hours:β-globin was amplified after 18 cycles from cells cultured either with EPO or TPO, whereas substantial amplification ofGpIIb and AchE was obtained only from cells cultured with TPO (Figure 3C). This last result reflects the high frequency of single 4A5+ (Table 4) ACHE+ (Table5) cells detected in those cultures.

As a negative control, purified single TER-119+ cells were also cultured under the same conditions. Very low numbers (5%-10%) of TER-119+ cells survived 24-48 hours even in the presence of EPO or TPO and did not provide amounts of cDNA sufficient for gene expression analysis (not shown).

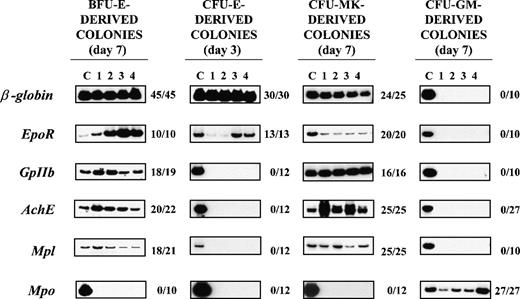

Expression of erythroid and megakaryocytic-specific genes in single colonies derived from normal progenitor cells

To evaluate the time span that normal hematopoietic progenitors remain bipotent, the expression of lineage-associated genes in single colonies derived from marrow progenitor cells was assessed by RT-PCR (Figure 4). cDNAs were obtained from single colonies derived from either early (CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-Mk) or late (CFU-E) progenitor cells induced to proliferate and differentiate in semisolid cultures by appropriate combinations of growth factors.49-51 The presence in the cDNA libraries of differentiation-associated genes (erythroid: β-globin andEpoR; megakaryocytic: GpIIb, AchE, andMpl; and granulocytic: Mpo) was then evaluated by PCR. To control for adequate amounts of cDNA, actin fragments were concurrently amplified from each library. Actin-specific cDNA fragments were amplified from 137 of a total of 140 single colonies processed (97% efficiency). Only actin-positive libraries were included in the analysis presented in Figure 4.

RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid(β-globin and EpoR), megakaryocytic (GpIIb,AchE, and Mpl), and myeloid (Mpo) genes in single colonies derived from early erythroid, megakaryocytic, and myeloid (BFU-E, CFU-Mk, and CFU-GM, respectively) or late erythroid (CFU-E) progenitor cells.

RNA was prepared from individual colonies (lanes 1-4), reverse transcribed, and PCR-amplified for either 24 (β-globin) or 35 (all the other genes) cycles. Actin-specific fragments were amplified from all the PCR reactions presented (not shown). Lane C shows the data obtained using complementary DNA (cDNA) from normal bone marrow (positive control). The results obtained with 4 representative colonies are shown in each panel. The ratio on the right of each panel specifies the actual number of single colonies that were positive for that particular gene as a function of the total number of colonies analyzed. The cloning efficiency was 32 ± 10 BFU-E–, 6 ± 2 CFU-Mk–, 10 ± 4 CFU-E–, and 55 ± 20 CFU-GM–derived colonies per 105 normal bone marrow cells, and the number of colonies analyzed corresponds to the colonies detected in 1.5, 4, 3, and 0.5 dishes, respectively. BFU-E = burst-forming unit erythroid; CFU-E = colony-forming unit–erythroid; CFU-GM = colony-forming unit–granulocyte macrophage; CFU-Mk = colony-forming unit–megakaryocyte.

RT-PCR analysis of the expression of erythroid(β-globin and EpoR), megakaryocytic (GpIIb,AchE, and Mpl), and myeloid (Mpo) genes in single colonies derived from early erythroid, megakaryocytic, and myeloid (BFU-E, CFU-Mk, and CFU-GM, respectively) or late erythroid (CFU-E) progenitor cells.

RNA was prepared from individual colonies (lanes 1-4), reverse transcribed, and PCR-amplified for either 24 (β-globin) or 35 (all the other genes) cycles. Actin-specific fragments were amplified from all the PCR reactions presented (not shown). Lane C shows the data obtained using complementary DNA (cDNA) from normal bone marrow (positive control). The results obtained with 4 representative colonies are shown in each panel. The ratio on the right of each panel specifies the actual number of single colonies that were positive for that particular gene as a function of the total number of colonies analyzed. The cloning efficiency was 32 ± 10 BFU-E–, 6 ± 2 CFU-Mk–, 10 ± 4 CFU-E–, and 55 ± 20 CFU-GM–derived colonies per 105 normal bone marrow cells, and the number of colonies analyzed corresponds to the colonies detected in 1.5, 4, 3, and 0.5 dishes, respectively. BFU-E = burst-forming unit erythroid; CFU-E = colony-forming unit–erythroid; CFU-GM = colony-forming unit–granulocyte macrophage; CFU-Mk = colony-forming unit–megakaryocyte.

Megakaryocytic-specific cDNAs (GpIIb, AchE, andMpl) were amplified from all 25 CFU-Mk–derived colonies and from a high proportion (86%-95%) of the single BFU-E–derived colonies analyzed (Figure 4). Conversely, erythroid-specific cDNAs(β-globin and EpoR) were amplified not only from all the BFU-E–derived colonies but also from 96%-100% of the CFU-Mk–derived colonies analyzed (Figure 4). It is possible that the amplification of erythroid (or megakaryocytic) genes from libraries prepared from single colonies was due to contamination from the originally plated marrow cells. To exclude this possibility, cDNAs were also prepared from 10 separate methylcellulose samples (10-20 μL each; ie, the same volume necessary to harvest a single colony), randomly removed from regions of the dish not containing colonies. Because actin was never amplified from those samples (not shown), we believe that cell contamination does not contribute in a detectable way to cDNA libraries prepared from the single colonies. It is also possible that the BFU-E– and CFU-Mk–derived colonies analyzed were CFU-Mix–derived colonies whose myeloid component had not been recognized by morphological evaluation. Although CFU-Mix–derived colonies were rare (2-4 colonies/105 cells), cDNA libraries were prepared from 17 of them and specific genes were amplified from these libraries as well. β-globin, EpoR, GpIIb, and Mpo were amplified from all 17 CFU-Mix–derived colonies analyzed, and AchE and Mplwere amplified from 16 of them (94%). The fact that Mpo was never amplified from the colonies identified as erythroid or megakaryocytic (Figure 4) supports the morphological observation that these colonies did not contain detectable myeloid cells.

The presence of erythroid and megakaryocytic genes was also analyzed in cDNA libraries prepared from 27 single CFU-GM–derived colonies and from 12 single CFU-E–derived colonies (Figure 4). Mpo was readily amplified from all 27 CFU-GM– derived colonies analyzed, whereas erythroid- and megakaryocytic-specific cDNAs were never amplified from these cDNAs (Figure 4). In contrast, erythroid (β-globin- and EpoR-) but not megakaryocytic (GpIIb, AchE, or Mpl) genes were readily amplified from libraries prepared from single CFU-E–derived colonies. Because CFU-E–derived colonies contain at most 50 cells, it is possible that the failure to detect megakaryocytic genes in those libraries was due to technical limitations. To exclude this possibility, cDNA libraries prepared from 7 separate pools of 5-20 individual CFU-E–derived colonies were analyzed as well. Althoughβ-globin was readily amplified from each of the pools, a very faint GpIIb band was amplified from only 2 of them andAchE and Mpl were never amplified (data not shown).

To evaluate whether the cells within a BFU-E–derived colony had the potential to generate megakaryocytic cells, single BFU-E–derived colonies were harvested at day 5 and transferred into secondary cultures stimulated with either EPO or TPO (Table6). Twenty-two single colonies of the total 24 harvested grew in secondary cultures, giving rise mostly to CFU-E–derived colonies (5 ± 3), with few (3 ± 2) single megakaryocytes, in the presence of EPO, and to many (on average 22 ± 9) single megakaryocytes when stimulated with TPO. Single GM colonies, similarly cultured into secondary cultures as control, proliferated very poorly (17%) under these conditions, giving rise to few clusters of macrophages and only in the presence of TPO.

Discussion

The failure to establish in vivo murine models of pure erythropoiesis by genetic strategies has suggested a linkage between erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation involving the presence of bipotent cell precursors.6,22-25,29-34 In this regard, a myeloid progenitor cell, capable of giving rise to cells of all the myeloid lineages, has been recently isolated and characterized (Traver D, et al, unpublished data, 1999). This myeloid progenitor generates in vitro 2 additional progenitor cell populations, 1 exclusively committed to the myelomonocytic lineage and the other 1 committed to the erythroid/megakaryocytic lineage.58 A similar bipotent E/Mk progenitor cell has been recently described in culture of human44 and murine45 bone marrow cells. This progenitor cell is apparently different from BFU-E and CFU-Mk that give rise to pure colonies containing only erythroid and megakaryocytic cells, respectively. These data suggested that, in the hemopoietic cell hierarchy, the last bipotent E/Mk cell is upstream to the BFU-E level.

Our working hypothesis was that a bipotent E/Mk cell should not only be present in hematopoietic tissues of normal mice, but its frequency should be increased following recovery from PHZ-induced anemia. To prove this hypothesis, we have investigated the expression of erythroid and megakaryocytic markers in the bone marrow and spleens of normal and PHZ-treated mice. These organs of PHZ-treated animals contained increased levels of both erythroid (TER-119+) and megakaryocytic (4A5+) cells (Figure 1A). Furthermore, at day 1, PHZ-treated spleens expressed high levels of both erythroid (β-globin and EpoR) and megakaryocytic (GpIIb, AchE, and Mpl) genes (Figure 1B). Therefore, despite the fact that PHZ-treated animals have been used as animal models for pure erythropoiesis,48megakaryocytopoiesis is also increased (at least transiently) in the tissues from these mice.

A population of TER-119+/4A5+ cells was noticed in the bone marrow of normal mice and its frequency increased from 1.3% to 3.8%-4.7% after PHZ-treatment (Figure 1A and Table 2). High numbers (1.3%-8.3% of the light density cells) of TER-119+/4A5+ cells were also detected in PHZ-treated spleens (Figure 1A, 1B, and Table 2). The presence of EDTA in the buffers used to manipulate the cells makes it unlikely that the antibodies were reacting against platelets (or their membranes) adherent to the surface of erythroblasts. Furthermore, fluorescence was expressed uniformly on all the cell surfaces under microscopic examination (Figure 2C). Therefore, TER-119 and 4A5/2D5 staining identifies cells expressing both erythroid and megakaryocytic markers whose frequency increases in hematopoietic tissues from mice recovering from PHZ-induced anemia. These results indicate the TER-119+/4A5+ cells as a potential candidate for the E/Mk precursor.

TER-119+/4A5+ cells were purified by several means from the spleens of PHZ-treated mice. GF starvation enriched TER-119+/4A5+ cells by ∼5-fold, whereas both immunomagnetic selection and cell sorting provided fractions enriched by ∼11-fold. In the case of immunomagnetic selection, ∼35% of the original TER-119+/4A5+ cells were recovered at the end of the purification (Table 3). The TER-119+/4A5+ cell fractions contained benzidine-negative (Table 1) and ACHE-negative (Table 4) blasts (Figure3B) expressing highly detectable levels of EpoR, Mpl,α-globin, and GpIIb, and low levels ofβ-globin and AchE by RT-PCR (Figure 2D and 3C). The fact that TER-119+/4A5+ cells were recognized by 2D5 (not shown) indicates that GpIIb expression is at the single-cell level. It was also interesting that TER-119+/4A5+ cells expressed almost as muchα-globin but much less β-globin than single TER-119+ cells (Figure 2D). Because activation ofα-globin precedes that of β-globin in the erythroid differentiation pathway,59 the difference in the levels ofα- and β-globin expression is consistent with the hypothesis that TER-119+/4A5+ cells are early precursor cells.

Although the TER-119+/4A5+ cells survived in the absence of GF for 18 hours, ∼80% of them died in the absence of EPO or TPO for 24-48 hours (Table 5) even in the presence of G-CSF or stem cell factor (data not shown). After 24-48 hours of culture in the presence of EPO, TER-119+/4A5+ cells gave rise to a cell population composed mainly (60%-75%) of single TER-119+ cells. After the same length of time, but in the presence of TPO, both TER-119+ (62%) and 4A5+ (11%-16%) cells were observed. It is unlikely that these differentiated cells developed from progenitor cells because of the low numbers of BFU-E, CFU-Mk, and CFU-E detected in the purified fractions. These results indicate that TER-119+/4A5+ blasts differentiate into erythroid and megakaryocytic cells within 24-48 hours of culture in the presence of EPO or TPO.

The observation that late differentiated cells, such as the TER-119+/4A5+ cells described in this manuscript, are still bipotent E/Mk precursors is apparently in contradiction with the report that, by careful morphological evaluation, normal murine BFU-E– and CFU-Mk–derived colonies do not contain cells for the other lineage. To clarify this point, we analyzed the expression of erythroid- and megakaryocytic-specific genes in single colonies derived in vitro from normal erythroid, megakaryocytic, and myeloid progenitor cells. Almost all (∼90%) of the colonies deriving from BFU-E and CFU-Mk, but none of the colonies derived from CFU-GM and CFU-E, contained significant numbers of cells expressing erythroid and megakaryocytic genes (Figure4). To confirm that the expression of megakaryocytic genes by a single BFU-E–derived colony was an index of the megakaryocytic potential of its cells and not of lineage-infidelity within the erythroid cells for megakaryocytic gene expression, single BFU-E–derived colonies were harvested at day 5 and transferred into secondary cultures stimulated only with TPO. A significant proportion (92%) of the single erythroid colonies gave rise to ACHE+ cells with a clear megakaryocyte morphology when cultured in the presence of TPO. This result indicates that, although megakaryocytes are not observed within BFU-E–derived colonies, almost all of them contain megakaryocyte precursors. Because we had analyzed a fair amount of all the colonies present in a culture dish (see legend to Figure 4), we conclude that normal BFU-E, and probably also CFU-Mk, are still bipotent for E/Mk differentiation. Therefore, as suggested by Axelrad et al,60 the normal E/Mk precursor is downstream to the BFU-E level.

The precise relationship of TER-119+/4A5+ cells with the progenitor cell compartments remains to be established. In fact, although progenitor cells were never detected among these cells, the normal bone marrow contains progenitor cells intermediate between BFU-E and CFU-E, the day 3 BFU-E61 that do not grow in the absence of serum (Migliaccio G, unpublished observation). It is also possible that TER-119+/4A5+ cells are generated by an alternative differentiation pathway during which cells remain bipotent after the CFU-E level to play an important physiological role in the recovery from PHZ-induced anemia. However, irrespective of their precise relationship with the progenitor cell compartments, TER-119+/4A5+ cells may provide a valuable tool to define the gene activation hierarchy during erythro-megakaryocytic differentiation in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs Sam Burstein and Thalia Papayannopoulou for suggestions and helpful discussions.

Supported by grants from Associazione Italiana per le Leucemie, Florence (“30 ore per la vita”), MURST 60%; and Grant CEE ERB-B104-CT96-0646 of the IV Framework Program of the European Community, Brussels, Belgium; by funds from Associazione Donatori Midollo Osseo, Florence, Italy; by a donation from Famiglia Yuja; and by institutional funds from Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy. C.C. was the recipient of a fellowship from FIRC (Milano, Italy).

Reprints:Alessandro Maria Vannucchi, Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit, Division of Hematology, Azienda Ospedaliera Careggi, 50134, Florence, Italy; e-mail: a.vannucchi@dfc.unifi.it.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.