Abstract

The mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) H3K4 methyltransferase protein, and the heterodimeric RUNX1/CBFβ transcription factor complex, are critical for definitive and adult hematopoiesis, and both are frequently targeted in human acute leukemia. We identified a physical and functional interaction between RUNX1 (AML1) and MLL and show that both are required to maintain the histone lysine 4 trimethyl mark (H3K4me3) at 2 critical regulatory regions of the AML1 target gene PU.1. Similar to CBFβ, we show that MLL binds to AML1 abrogating its proteasome-dependent degradation. Furthermore, a subset of previously uncharacterized frame-shift and missense mutations at the N terminus of AML1, found in MDS and AML patients, impairs its interaction with MLL, resulting in loss of the H3K4me3 mark within PU.1 regulatory regions, and decreased PU.1 expression. The interaction between MLL and AML1 provides a mechanism for the sequence-specific binding of MLL to DNA, and identifies RUNX1 target genes as potential effectors of MLL function.

Introduction

The transcriptional regulation of hematopoiesis requires coordinate changes in gene expression to control the processes of stem cell self-renewal, differentiation, and maturation. The primary importance of transcriptional regulation in hematopoiesis is exemplified by human acute myelogenous leukemia, where recurrent chromosomal translocations are found that affect transcriptional regulators including transcription factors and histone modifying enzymes, such as AML1, CBFβ, RARα, TEL, MLL, MOZ, CBP, and p300.1,2 Acute leukemias accompanied by MLL translocations have traditionally been thought of being distinct from the CBF leukemias (those associated with AML1 or CBFβ translocations) at least in part because of their different gene expression profile, different prognosis, and different frequency of occurrence in de novo versus secondary AML. Yet mutations and translocations involving the mixed-lineage leukemia and AML1 genes are found in both AML and ALL, and it has been postulated that MLL and AML1/CBFβ may both participate in regulating some common target genes.3

The MLL gene was isolated as a common target of chromosomal translocations involving 11q23.4-6 These translocations, which are observed in adult, childhood, and infant acute leukemias, fuse MLL with more than 60 different partner proteins. However, the most common translocations generate the MLL/AF6, MLL/AF9, MLL/ENL(s), MLL/AF10, and the MLL/AF17 fusion proteins in AML, and the MLL/AF4, MLL/LAF4, MLL/5q31, and MLL/ENL(l) fusion proteins in B-ALL.7 MLL is a functional ortholog of the Drosophila trithorax (trx) protein,8 which is involved in maintaining epigenetic transcriptional memory at homeobox (Hox) gene loci.9 The SET domain of MLL has histone methyltransferase activity10 and MLL forms a multicomponent complex that specifically methylates lysine 4 on histone H3 (H3-K4), a modification typically associated with transcriptionally active regions of chromatin. The best-studied downstream targets of MLL (and trx) are the Hox genes, which control segment pecificity and cell fate in the developing embryo.11 Targeted homozygous disruption of MLL in mice was embryonic lethal at day 10.5-14,12 and similar to loss of trx function in flies, Hox gene expression was initiated but not maintained in these mice.13 Another group, who targeted exons 12-14 of Mll, obtained a slight delay in lethality,14 but both groups reported that Mll-deficient mice have defective yolk sac and fetal liver hematopoiesis.15 Animals carrying a single normal Mll allele are phenotypically abnormal, with mild anemia and thrombocytopenia,12,14 and studies using chimeric mice reconstituted with Mll deficient or hemizygous embryonic stem cells suggest that Mll is essential for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) development itself or for the transition of HSC to multipotent progenitors.16 Thus 2 copies of the Mll gene are essential for normal hematopoietic development. By regulating Hox gene activity, Mll can influence progenitor cell expansion.16 Although the Hox gene locus has been extensively studied as a target of MLL (and the leukemia-associated MLL fusion proteins), additional downstream targets of MLL need to be identified.

RUNX proteins, which include AML1 (RUNX1), AML2 (RUNX3), and AML3 (RUNX2), are involved in hematologic, skeletal, gastric, and neural development.17 AML1 and its required heterodimeric partner, CBFβ, are 2 of the most frequently deregulated genes in human acute leukemia through translocations (generating AML1-ETO and CBFβ-SMMHC in AML, and TEL-AML1 in B-ALL), mutations or gene amplification. Mono-allelic mutations in AML1 have been found in affected individuals with FPD/AML (familial platelet disorder [FPD] with a predisposition to AML), de novo AML, and in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), whereas bi-allelic mutations have been found primarily in AML M0 patients.18 AML1 and CBFβ are required for the establishment of definitive hematopoiesis in mice,19,20 although the conditional knockout of AML1 has demonstrated that AML1 is not essential for adult hematopoiesis. Rather, loss of AML1 in adult mice results in thrombocytopenia, expansion of the myeloid compartment (with an increase in myeloid progenitors), and defective T- and B-cell development.21 AML1 can function to activate or repress gene expression22 and recruitment of critical chromatin modifiers, such as MOZ, p300/CBP, Suv39H1, PRMT1, Sin3, and HDACs, by AML1 may explain its promoter-specific effects.23-25 Although knockout of several of these AML1-interacting proteins in mice results in hematopoietic phenotypes, they generally differ from the phenotype of Aml1−/−or Cbfβ−/− mice.

Here we demonstrate that MLL binds to the amino-terminus of AML1 and abrogates its ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. Furthermore, we show that both MLL and AML1/CBFβ are required for maintaining the H3K4-me3 mark at the PU.1 upstream regulatory element (URE) and promoter region, and for full PU.1 gene expression. We examined a series of MDS and leukemia-associated AML1 frame-shift mutations and missense mutations, which do not alter DNA binding or CBFβ binding, and found that many of them affect the interaction between AML1 and MLL. Disruption of the interactions between AML1 and MLL by these mutations leads to defective regulation of AML1 target gene expression, reduced Mll binding and H3K4me3 at PU.1 regulatory regions, and decreased PU.1 expression. The physical and functional interaction of MLL with AML1 broadens the range of MLL target genes, promoting the expression of AML1 target genes.

Methods

Constructs, shRNA, and cell cultures

The shRNA for Aml1, Cbfβ, MLL were obtained from Open Biosystems Cells (416B and 293T) were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS. Human erythroleukemia line (HEL) cells were maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS. Stable cell lines of 416B were generated by lentiviral infection with pLKO.1-based shRNA constructs, followed by selection with puromycin for 1 week beginning 48 hours after infection. Expression of F-MLL or F-MLL–ΔSET was accomplished by co-transfection pCXN2 F-MLL or F-MLL–ΔSET with the pGK-Neo expression vector followed by 2 weeks selection in G418, that started 48 hours after transfection. Expression of wild-type AML1 or AML1 (R139Q) was accomplished by retroviral infection with a MigR1 construct (MigR1, MigR1-AML1, or MigR1-AML1 [R139Q]) followed by FACS sorting of the GFP positive cells. The experiments using primary mouse hematopoietic cells were performed using lineage− c-Kit+ bone marrow Cells obtained from 5-FU–treated C57Bl6 mice. The cells were infected with 1 of the 2 MLL-directed lentiviral shRNAs and selected with puromycin for 2 days beginning 24 hours after infection.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were done on indicated cell (2 × 106 cells/1 ChIP) DNA using EZ ChIP (Upstate Biotechnology) and following the manufacturer's protocols with some modifications. Formaldehyde was added to the cells in a culture dish to a final concentration of 1% and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. The cells were washed in 1 mL of ice-cold PBS with proteinase inhibitors, scraped, and resuspended in 400 μL of SDS lysis buffer. Lysates were sonicated for 10 seconds 9 times on ice with 10 second pulses on wet ice and centrifuged at 21 130g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were loaded on 1% agarose gels and determined to have DNA lengths between 200 and 1000 bp. The sonicated samples were precleaned with salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose beads (Upstate Biotechnology). The soluble chromatin fraction was collected, and 8 μL of antibody for acetyl-H3, acetyl-H4, trimethyl-H3-K4 (H3K4me3), or antibody for polyclonal rabbit antibody to PU.1 (Spi-1, Santa Cruz sc-352), polyclonal rabbit antibody to AML1 (CST no. 4334), IgG control antibody or no antibody, was added and incubated overnight with rotation. All histone antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. After rotation, chromatin-antibody complexes were collected using salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose beads and washed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Immunoprecipitated DNA was recovered using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and analyzed by direct PCR or q-PCR. We used previously reported primers designed to separately amplify different regions in the PU.1 locus. One additional primer set was used to amplify the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene as an internal control. Relative enrichments for histone antibodies were calculated by taking the ratio between the net intensity of the PU.1 PCR product from each primer set and the net intensity of the GAPDH PCR product for the bound sample and dividing this by the same ratio calculated for the input sample. Relative enrichments for PU.1 and AML1 antibodies were calculated by taking the ratio between the net intensity of the PU.1 PCR product from each primer set and the net intensity for the bound sample of the IgG control and dividing this by the same ratio calculated for the input sample. The value of each point was calculated as the average from 2 independent ChIP experiments and a total of 4 independent PCR analyses.

Real-time RT-PCR

We extracted RNA using the RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN), reverse transcribed it and then amplified it using an ABIPrism 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems) with the following parameters: 48°C (30 minutes), 95°C (10 minutes), followed by 40 cycles of 95°C (15 seconds) and 60°C (1 minute). The primers are shown in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Western blot assay

We prepared total cell lysates as described, resolved proteins by SDS-PAGE, and electrotransferred them to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). We used polyclonal rabbit antibody to AML1 (CST, 4334), PU.1 (Spi-1; Santa Cruz sc-352), and monoclonal mouse antibody to CBFβ (MBL, D127-3), Flag (Sigma-Aldrich; F3165). We detected immunoreactive proteins using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies to rabbit or mouse (Amersham; NA934V) and the ECL detection system (Amersham; RPN2132).

The Student t test was used to determine the statistical differences between various experimental and control groups. The difference was considered statistically significant when *P < .05 or **P < .01.

Results

Interaction of MLL and AML1

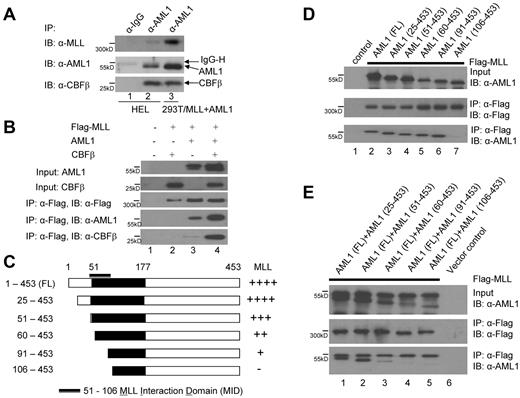

AML1 has been shown to interact with SET domain containing proteins, including Suv39H1,24,25 which prompted us to look for a direct interaction between MLL and AML1. We first showed that the endogenous MLL and AML1 proteins interact in HEL cells, performing coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays with anti-AML1 antibodies in the presence of a DNA intercalating agent, ethidium bromide (50 μg/mL), followed by immunoblotting with anti-MLL, anti-AML1, and anti-CBFβ antibodies (Figure 1A lanes 1-2); transiently transfected Flag tagged MLL and untagged AML1 were used as the positive control for the IP (Figure 1A lane 3). We next coexpressed MLL with AML1 in 293T cells and used co-IP assays (in the presence of ethidium bromide) to confirm and examine their interaction. MLL interacts with AML1 in the absence of CBFβ, but also when CBFβ is present (Figure 1B lanes 3-4). Using a series of AML1 N-terminal deletion constructs: [AML1 (1-453, 25-453, 51-453, 60-453, 91-453, and 106-453; Figure 1C)], we determined that MLL interacts with the N-terminal portion of the Runt-domain and the region N-terminal to it, involving the region between amino acids 91 and 106 (Figure 1D). We also examined the competitive interaction between MLL and the N-terminal deletion mutants in the presence of full-length AML1 (Figure 1E). Although AML1 (25-453) and AML1 (51-453) bind MLL as well as wild type (1-453) AML1, further N terminal deletions (60-453, 91-453) gradually reduce MLL binding and the AML1 (106-453) deletion mutant completely loses its interaction with MLL (Figure 1D lane 7 and Figure 1E lane 5). In the presence of full-length AML1, N-terminal deletions (60-453 and 91-453) showed weaker interaction with MLL comparing with full-length AML1 or AML1 (51-453; Figure 1E lanes 2-4), even though the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and nuclear matrix localization signal (NMLS) of AML1 are located within amino acids 170-185 and amino acids 331-371, respectively.17 Thus, the lack of MLL binding to the 106-453 deletion mutant AML1 protein reflects loss of the MLL interacting domain (MID), which spans amino acids 51-60 and 91-106 of AML1.

Physical interaction between MLL and AML1. (A) Interaction between the endogenous MLL and AML1 proteins in HEL cells. HEL cell nuclear lysates were used for immunoprecipitation (lane 1-2) with IgG and anti-AML1 polyclonal antibodies cross-linked with protein A sepharose beads followed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. Nuclear lysates prepared from 293T cells that coexpress Flag tagged MLL and AML1 were used as an IP control (lane 3) with the anti-AML1 polyclonal antibodies cross-linked with protein A sepharose beads. (B) Interaction of MLL and AML1 when both are expressed in 293T cells in the absence or presence of CBFβ, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot. The transfections were indicated as in lane 1, vector alone; lane 2, Flag tagged MLL and CBFβ; lane 3, Flag tagged MLL and AML1; and lane 4, Flag tagged MLL, AML1, and CBFβ. Row 1 indicates AML1 input, row 2 indicates CBFβ input, row 3 indicates Flag tagged MLL IP and Western blot, row 4 indicates Western blot of AML1 with IP samples in row 3, and row 5 indicates Western blot of CBFβ with IP samples in row 3. (C) Diagram of a series of AML1 N-terminal deletion constructs: AML1 (1-453, 25-453, 51-453, 60-453, 90-453, and 106-453), and the strength of their interaction with MLL as indicated (either – or + derived from experiment in panel E). (D) Determination of the MLL interacting domain in AML1 by IP and Western blot using the N-terminal deletion constructs of AML1 shown in panel C. (E) Competitive interaction between MLL and full-length AML1 and coexpressed N-terminal deletion constructs of AML1 in 293T cells. The upper band in lanes 1-5, top panel indicate AML1 (1-453), while the lower band in lanes 1-5 indicate AML1 (25-453, 51-453, 60-453, 90-453, and 106-453). The bands (both upper and lower) in lanes 1-3, bottom panel indicate the same bands as the top panel, whereas lanes 4-5 indicate only the AML1 (1-453) band, but not the AML1 (90-453 or 106-453) bands.

Physical interaction between MLL and AML1. (A) Interaction between the endogenous MLL and AML1 proteins in HEL cells. HEL cell nuclear lysates were used for immunoprecipitation (lane 1-2) with IgG and anti-AML1 polyclonal antibodies cross-linked with protein A sepharose beads followed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. Nuclear lysates prepared from 293T cells that coexpress Flag tagged MLL and AML1 were used as an IP control (lane 3) with the anti-AML1 polyclonal antibodies cross-linked with protein A sepharose beads. (B) Interaction of MLL and AML1 when both are expressed in 293T cells in the absence or presence of CBFβ, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot. The transfections were indicated as in lane 1, vector alone; lane 2, Flag tagged MLL and CBFβ; lane 3, Flag tagged MLL and AML1; and lane 4, Flag tagged MLL, AML1, and CBFβ. Row 1 indicates AML1 input, row 2 indicates CBFβ input, row 3 indicates Flag tagged MLL IP and Western blot, row 4 indicates Western blot of AML1 with IP samples in row 3, and row 5 indicates Western blot of CBFβ with IP samples in row 3. (C) Diagram of a series of AML1 N-terminal deletion constructs: AML1 (1-453, 25-453, 51-453, 60-453, 90-453, and 106-453), and the strength of their interaction with MLL as indicated (either – or + derived from experiment in panel E). (D) Determination of the MLL interacting domain in AML1 by IP and Western blot using the N-terminal deletion constructs of AML1 shown in panel C. (E) Competitive interaction between MLL and full-length AML1 and coexpressed N-terminal deletion constructs of AML1 in 293T cells. The upper band in lanes 1-5, top panel indicate AML1 (1-453), while the lower band in lanes 1-5 indicate AML1 (25-453, 51-453, 60-453, 90-453, and 106-453). The bands (both upper and lower) in lanes 1-3, bottom panel indicate the same bands as the top panel, whereas lanes 4-5 indicate only the AML1 (1-453) band, but not the AML1 (90-453 or 106-453) bands.

Mll is required for H3K4 tri-methylation at PU.1 regulatory regions

We have shown that Aml1 is critical for appropriate PU.1 gene regulation by the PU.1 URE.21

To determine whether Mll is responsible for H3K4 trimethylation at the PU.1 locus, we knocked down Mll using shRNAs in the early myeloid murine progenitor cell line 416B. We established an Mll knockdown cell line, and after confirming the knockdown by real-time PCR and Western blotting (Figure 2A), demonstrated reduced H3K4 tri-methylation at both the PU.1 URE and promoter regions (Figure 2B lanes 2-5), as well as reduced PU.1 expression (lane 2 in Figure 2A). Reintroduction of full-length human MLL (lacking the 3′ UTR, which is targeted by the shRNA), but not its SET domain deletion mutant form (MLL-ΔSET), rescued both the H3K4me3 mark (Figure 2C lanes 2-5) and PU.1 expression (Figure 2D lanes 2-3). To validate our finding in primary hematopoietic cells, we performed Mll knockdown with 2 different Mll-directed shRNAs in mouse lineage− c-Kit+ bone marrow cells, and after confirming Mll knockdown (Figure 2E row 1 lanes 2-3), demonstrated reduced Aml1 expression (Figure 2E row 2 lanes 2-3), and reduced PU.1 expression (Figure 2E row 3 lanes 2-3) by Western blotting. Thus, the methyltransferase activity of Mll is required for the maintenance of the H3K4 tri-methylation mark within the PU.1 locus and for proper regulation of PU.1 gene expression.

Mll dictates the level of H3K4 tri-methylation at PU.1 regulatory regions. (A) Western blot of nuclear extracts from control cells (lane1) and Mll knockdown cells (lane 2) with indicated antibodies, anti-MLL, anti-AML1, anti-PU.1, anti-H3, anti-H3K4me3, and anti-actin. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed using H3K4 tri-methylation specific antibodies and multiple primer sets to assay H3K4me3 levels at the PU.1 locus to detect the effects of shRNA-mediated knockdown of Mll in the early myeloid progenitor 416B cells. The ChIP primers localized at 1, 5′ URE; 2, 3′URE; 3, −5kb; 4, promoter; 5, +0.4 kb; 6, +6 kb; 7, +17 kb at PU.1 locus; 8, control primers at Gapdh gene locus. (C) Rescue of the H3K4me3 marks in the PU.1 URE and promoter regions after reintroduction of full-length human MLL, but not a deletion mutant form (MLL-ΔSET) that lacks a SET domain; in 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll. (D) IP or direct Western blot with indicated antibodies in established MLL and MLL-ΔSET stable expression 416B cell lines: lane 1, 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll; lane 2, 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll and overexpress Flag tagged MLL; lane 3, 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll and overexpress Flag tagged MLL-ΔSET. Row 1 indicates IP with anti-Flag beads and Western blot with Flag antibodies; row 2 indicated direct Western blot with anti-PU.1 antibodies; and row 3 indicated direct Western blot with anti-actin antibodies. (E) Western blots of nuclear extracts isolated from pLKO.1 infected control bone marrow Lin− c-Kit+ cells (lane 1) and Mll knockdown cells (lane 2-3) using anti-MLL, anti-AML1, anti-PU.1, and anti-actin antibodies.

Mll dictates the level of H3K4 tri-methylation at PU.1 regulatory regions. (A) Western blot of nuclear extracts from control cells (lane1) and Mll knockdown cells (lane 2) with indicated antibodies, anti-MLL, anti-AML1, anti-PU.1, anti-H3, anti-H3K4me3, and anti-actin. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed using H3K4 tri-methylation specific antibodies and multiple primer sets to assay H3K4me3 levels at the PU.1 locus to detect the effects of shRNA-mediated knockdown of Mll in the early myeloid progenitor 416B cells. The ChIP primers localized at 1, 5′ URE; 2, 3′URE; 3, −5kb; 4, promoter; 5, +0.4 kb; 6, +6 kb; 7, +17 kb at PU.1 locus; 8, control primers at Gapdh gene locus. (C) Rescue of the H3K4me3 marks in the PU.1 URE and promoter regions after reintroduction of full-length human MLL, but not a deletion mutant form (MLL-ΔSET) that lacks a SET domain; in 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll. (D) IP or direct Western blot with indicated antibodies in established MLL and MLL-ΔSET stable expression 416B cell lines: lane 1, 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll; lane 2, 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll and overexpress Flag tagged MLL; lane 3, 416B cells that express shRNA knock down of the Mll and overexpress Flag tagged MLL-ΔSET. Row 1 indicates IP with anti-Flag beads and Western blot with Flag antibodies; row 2 indicated direct Western blot with anti-PU.1 antibodies; and row 3 indicated direct Western blot with anti-actin antibodies. (E) Western blots of nuclear extracts isolated from pLKO.1 infected control bone marrow Lin− c-Kit+ cells (lane 1) and Mll knockdown cells (lane 2-3) using anti-MLL, anti-AML1, anti-PU.1, and anti-actin antibodies.

Aml1/Cbfβ are required for maintaining H3K4 tri-methylation at PU.1 regulatory regions

To verify that maintenance of H3K4 trimethylation within the PU.1 locus is truly Aml1/Cbfβ dependent, we knocked-down Aml1 and Cbfβ with specific shRNAs in 416B cells. Knockdown of either Aml1 or Cbfβ reduced H3K4 trimethylation at both the PU.1 URE and promoter regions, as well as PU.1 expression (Figure 3A lanes 2-5). We confirmed efficient knockdown of Aml1 or Cbfβ in the cell lines by Western blot analysis (Figure 3B lanes 3-4). To demonstrate that this is an Aml1-dependent effect, we show that reintroduction of wild-type human AML1, but not a DNA binding mutant form (R139Q) of AML1, both lacking the DNA sequences targeted by the shRNA, rescues the H3K4me3 mark and restores PU.1 expression in the Aml1 knockdown cell line (Figure 3C lanes 2-5). The level of AML1 and AML1 (R139Q) protein expression is shown in Figure 3D. Thus, both the Aml1/Cbfβ complex and MLL are required for proper maintenance of the H3K4 trimethyl mark within the PU.1 locus.

Both Aml1 and Cbfβ are required for maintaining H3K4 tri-methylation at PU.1 regulatory regions. (A) ChIP assays were performed to assess the level of H3K4 trimethylation at the PU.1 locus in 416B cells in which knockdown of either Aml1 or Cbfβ was accomplished using specific shRNAs. (B) Reduction in PU.1 levels following knockdown of either Aml1 or Cbfβ. Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, anti-CBFβ; row 3, anti-PU.1) with controls (lane 1-2) and Aml1 and Cbfβ knockdown cells (lane 3-4). (C) Rescue of the H3K4me3 mark within the PU.1 URE and promoter regions following reintroduction of wild-type human AML1, but not a DNA binding mutant form of AML1 (R139Q). (D) Loss of PU.1 expression following knockdown of AML1, which could be restored following AML1 overexpression, but not AML1 (R139Q) overexpression. Western blot using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, anti-CBFβ; row 3, anti-PU.1) with controls (lane 1-2) and AML1 (lane 3) and AML1 (R139Q; lane 4) overexpression in Aml1 knockdown cells.

Both Aml1 and Cbfβ are required for maintaining H3K4 tri-methylation at PU.1 regulatory regions. (A) ChIP assays were performed to assess the level of H3K4 trimethylation at the PU.1 locus in 416B cells in which knockdown of either Aml1 or Cbfβ was accomplished using specific shRNAs. (B) Reduction in PU.1 levels following knockdown of either Aml1 or Cbfβ. Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, anti-CBFβ; row 3, anti-PU.1) with controls (lane 1-2) and Aml1 and Cbfβ knockdown cells (lane 3-4). (C) Rescue of the H3K4me3 mark within the PU.1 URE and promoter regions following reintroduction of wild-type human AML1, but not a DNA binding mutant form of AML1 (R139Q). (D) Loss of PU.1 expression following knockdown of AML1, which could be restored following AML1 overexpression, but not AML1 (R139Q) overexpression. Western blot using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, anti-CBFβ; row 3, anti-PU.1) with controls (lane 1-2) and AML1 (lane 3) and AML1 (R139Q; lane 4) overexpression in Aml1 knockdown cells.

MLL stabilizes AML1 from ubiquitin-proteasome mediated degradation

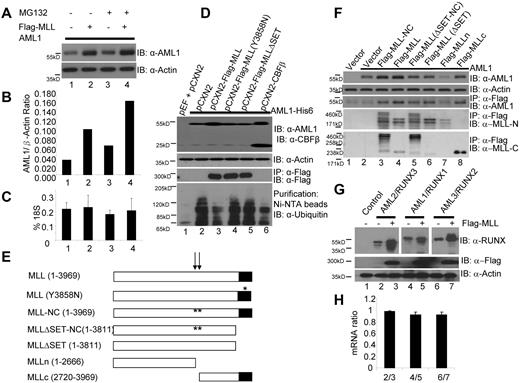

To address the functional relationship between MLL and AML1, we cotransfected 293T cells with both MLL and AML1, and found that the level of AML1 protein was significantly increased by coexpression of MLL (Figure 4A-B lanes 1-2), even though real-time PCR showed no difference in the amount of AML1 mRNA (Figure 4C lanes 1-2). MLL coexpression stabilizes AML1 to a greater extent than a 3 hour exposure to the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 4A-B lane 3). Thus, MLL appears to affect the translation and/or protein stability of AML1. This stabilization by MLL is specific to AML1, as CBFβ protein expression is not up-regulated in the same coexpression experiments (Figure 1B lanes 2-4 and data not shown). To confirm this effect of MLL we used the Mll knock down 416B cells, and found reduced Aml1 protein but not mRNA level (data not shown) in those cells (Figure 2B lane 2). We next measured the polyubiquitination of AML1 after the transient coexpression of AML1 with one of the following MLL constructs: MLL (1-3969), MLL-Y3858N, MLL-ΔSET (1-3811), and CBFβ in 293T cells. We found reduced polyubiquitination of AML1 when either MLL or CBFβ was coexpressed (Figure 4D lanes 3-6), but not when AML1 was coexpressed with the MLL mutants (MLL-Y3858N and MLL-ΔSET; Figure 4D lanes 4-5). Thus, like Cbfβ, wild-type Mll stabilizes Aml1 protein, and interferes with its ubiquitin-proteasome mediated degradation in vivo.26

MLL stabilizes AML1. (A) Stabilization of AML1 in 293T cells by coexpression of MLL or presence of MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. (B) Ratio of AML1/β-Actin is determined by densitometry based on the Western blot in Figure 4A. (C) Real-time PCR measurement of AML1 mRNA levels in experiment shown in Figure 4A. (D) Inhibition of AML1 poly-ubiquitination by coexpression of CBFβ and wild-type MLL but not MLL mutants. Lane 1, transfection control; lane 2, AML1-His6 with pCXN2 vector; lane 3, AML1-His6 with Flag-MLL; lane 4, AML1-His6 with Flag-MLL (Y3858N); lane 5, AML1-His6 with Flag-MLLΔSET; lane 6, AML1-His6 with CBFβ. Western blots were performed using the indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1 and anti-CBFβ; row 2, anti-actin; row 3, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-Flag; row 4, His-tag AML1 were affinity purified with Ni-NTA magnetic Agarose beads and IB with anti-ubiquitin). (E) Diagram of a series of MLL deletion mutant constructs: MLL (1-3969), MLL (Y3858N), MLL-NC (1-3969), MLLΔSET-NC (1-3811), MLL ΔSET (1-3811), MLLn (1-2666), and MLLc (2720-3969). The arrows indicate 2 taspase I processing sites and the stars indicate the sites of the taspase I processing site mutations (cleavage site 1 mutation, D2666A/G2667A; cleavage site 2 mutation, D2718A/G2719A). (F) Interaction between AML1 and MLL deletion proteins. Lane 1, transfection control; lane 2, AML1 with pCXN2 vector; lane 3, AML1 with Flag-MLL-NC (noncleavable); lane 4, AML1 with Flag-MLL; lane 5, AML1 with Flag-MLLΔSET-NC; lane 6, AML1 with Flag-MLL-ΔSET; lane 7, AML1 with Flag-MLLn; and lane 8, AML1 with Flag-MLLc. Western blots were done using the indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, anti-actin; row 3, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-AML1; row 4, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-MLLn; row 5, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-MLLc). (G) Stabilization of AML1 family proteins (AML1, AML2, and AML3) by MLL. AML2 was expressed in lane 2 and 3. AML1 was expressed in lane 4 and 5. AML3 was expressed in lane 6 and 7. Flag-MLL was expressed in lane 3, 5, and 7. Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-RUNX; row 2, anti-Flag; row 3, anti-actin). Spaces have been inserted in the top panel to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (H) AML2, AML1, and AML3 mRNA expression level ratios measured by real-time PCR assay in experiment of 4G. Lane 1, AML2 mRNA levels ratio between AML2 without MLL/AML2 with MLL; lane 2, AML1 mRNA levels ratio between AML1 without MLL/AML1 with MLL; lane 3, AML2 mRNA levels ratio between AML3 without MLL/AML3 with MLL.

MLL stabilizes AML1. (A) Stabilization of AML1 in 293T cells by coexpression of MLL or presence of MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. (B) Ratio of AML1/β-Actin is determined by densitometry based on the Western blot in Figure 4A. (C) Real-time PCR measurement of AML1 mRNA levels in experiment shown in Figure 4A. (D) Inhibition of AML1 poly-ubiquitination by coexpression of CBFβ and wild-type MLL but not MLL mutants. Lane 1, transfection control; lane 2, AML1-His6 with pCXN2 vector; lane 3, AML1-His6 with Flag-MLL; lane 4, AML1-His6 with Flag-MLL (Y3858N); lane 5, AML1-His6 with Flag-MLLΔSET; lane 6, AML1-His6 with CBFβ. Western blots were performed using the indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1 and anti-CBFβ; row 2, anti-actin; row 3, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-Flag; row 4, His-tag AML1 were affinity purified with Ni-NTA magnetic Agarose beads and IB with anti-ubiquitin). (E) Diagram of a series of MLL deletion mutant constructs: MLL (1-3969), MLL (Y3858N), MLL-NC (1-3969), MLLΔSET-NC (1-3811), MLL ΔSET (1-3811), MLLn (1-2666), and MLLc (2720-3969). The arrows indicate 2 taspase I processing sites and the stars indicate the sites of the taspase I processing site mutations (cleavage site 1 mutation, D2666A/G2667A; cleavage site 2 mutation, D2718A/G2719A). (F) Interaction between AML1 and MLL deletion proteins. Lane 1, transfection control; lane 2, AML1 with pCXN2 vector; lane 3, AML1 with Flag-MLL-NC (noncleavable); lane 4, AML1 with Flag-MLL; lane 5, AML1 with Flag-MLLΔSET-NC; lane 6, AML1 with Flag-MLL-ΔSET; lane 7, AML1 with Flag-MLLn; and lane 8, AML1 with Flag-MLLc. Western blots were done using the indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, anti-actin; row 3, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-AML1; row 4, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-MLLn; row 5, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-MLLc). (G) Stabilization of AML1 family proteins (AML1, AML2, and AML3) by MLL. AML2 was expressed in lane 2 and 3. AML1 was expressed in lane 4 and 5. AML3 was expressed in lane 6 and 7. Flag-MLL was expressed in lane 3, 5, and 7. Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-RUNX; row 2, anti-Flag; row 3, anti-actin). Spaces have been inserted in the top panel to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (H) AML2, AML1, and AML3 mRNA expression level ratios measured by real-time PCR assay in experiment of 4G. Lane 1, AML2 mRNA levels ratio between AML2 without MLL/AML2 with MLL; lane 2, AML1 mRNA levels ratio between AML1 without MLL/AML1 with MLL; lane 3, AML2 mRNA levels ratio between AML3 without MLL/AML3 with MLL.

To identify the AML1-interacting and stabilizing domain(s) within MLL, we cotransfected AML1 with the following MLL deletion constructs: MLL (1-3969), MLL-ΔSET (1-3811), MLLn (1-2666), MLLc (2720-3996), and two Taspase I cleavage site mutant proteins MLL-NC (1-3969), MLL-ΔSET-NC (1-3811), and performed co-IP experiments (Figure 4E). The wild-type and noncleavable mutant full-length MLL proteins strongly interact with AML1 and increase AML1 protein levels (Figure 4F top panel lanes 3-4). The wild-type and noncleavable mutant MLL-ΔSET proteins still interact with AML1, but they do not increase AML1 protein levels as potently as full-length MLL (Figure 4F lanes 5-6). Further deletion of the C-terminal of MLL eliminates its interaction with AML1 (Figure 4F lane 7). Deletion of N-terminal portions of MLL maintains its interactions with AML1, but does not increase AML1 protein levels as well as full-length MLL (Figure 4F lane 8). Our data suggest that the interaction of MLL with AML1 requires the C-terminal domain (2720-3969), but to increase AML1 protein levels requires both the N-terminal domain (1-2666) and C-terminal domain (2720-3969). Given that the nuclear localization signal is located in the N-terminal domain and the AML1 interaction domain in the C-terminal of MLL, it follows that the intact MLL protein has the greatest ability to interact with AML1 and increase its levels.

Because the MLL interaction domain in AML1 protein is highly conserved among other members of AML1 family (AML2 and AML3), we further demonstrated that MLL can increase the level of all 3 AML proteins (AML1, AML2, and AML3) after transient transfection (Figure 4G), as real-time PCR showed no difference in the levels of AML1, 2, and 3 mRNA in the presence or absence of MLL (Figure 4H)

The interaction between MLL and AML1 is impaired in some mutant forms of AML1 found in MDS or AML patients

Having shown that MLL interacts with AML1 directly, and regulates its protein level, we examined whether the MLL-AML1 interaction is impaired by some of the AML1 mutations found in human MDS or AML patients, in particular those located within the MID (Figure 5A). We examined the interaction of these AML1 mutant proteins with MLL, and whether the mutant proteins could interfere with the interaction of MLL with wild type AML1, which is expressed in all cells containing a wild-type allele. Surprisingly, we found that the frame-shift mutations, which create short N-terminal fragments of AML1 that are 57 aa or longer, bind MLL well (Figure 5B bottom panel) but also inhibit the interaction of MLL with the wild-type AML1 protein (Figure 5B lanes 3-6 next to bottom panel). This suggests that they bind MLL with a higher than normal affinity. Next, we examined 8 missense mutations that localize close to or within the MID (L29S, A33V, G42R, R49H, R49S, H58N, V63A, and S67I)27-32 and all significantly impair the interaction with MLL (Figure 5C lanes 3-10). In contrast, the AML1 mutant with impaired DNA binding (W79C; lane 11) binds MLL similarly as the wild-type AML1 (lane 2).

The interaction between MLL and AML1 is impaired by some mutant AML1 proteins found in leukemia patients. (A) Diagram of a series of the N-terminal frame shift and misssense mutations. The black bar indicates the MID. The black area indicates the Runt-domain. The black x's indicate missense mutation of AML1 found in MID (details in Figure 5C). (B) The AML1 frame shift mutants interact with MLL and block the interaction between wild-type AML1 and MLL. Lane 1, transfection control; lane 2, AML1 with vector control; lane3, AML1 with AML1 (1-57); lane 4, AML1 with AML1 (1-72); lane 5, AML1 with AML 1(1-91); and lane 6, AML1 with AML1 (1-105). Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-Flag; row 3, IP with anti-Flag, running with 10% SDS-PAGE gel and IB with anti-AML1; and row 4, IP with anti-Flag, running with 20% SDS-PAGE gel and IB with anti–AML1-N). (C) The N-terminal missense mutations of AML1 impair MLL interaction. Lane 1, transfection with pCS2 vector control and AML1; lane 2, MLL with AML1; lane 3, MLL with AML1 (L29S); lane 4, MLL with AML1 (A33V); lane 5, MLL with AML1 (G42R); lane 6, MLL with AML1 (R49H); lane 7, MLL with AML1 (R49S); lane 8, MLL with AML1 (H58N); lane 9, MLL with AML1 (V63A); lane 10, MLL with AML1 (S67I); and lane 11, MLL with AML1 (W79C). Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-Flag; and row 3, IP with anti-Flag, IB with anti-AML1). (D) ChIP assay with anti-MLL antibodies and with primer set at 3′URE region of PU.1 gene (Figure 2A primer set 2) with 416B stable cell lines: 1, pBEX; 2, pBEX-AML1; 3, pBEX-AML1 (1-91); 4, pBEX-AML1 (1-105); 5, pBEX-AML1 (L29S); 6, pBEX-AML1 (H58N); 7, pBEX-AML1 (R139Q); and 8, pBEX-AML1 (R177Q). (E) ChIP assay with anti-H3K4me3 antibodies and with primer set at 3′URE region of PU.1 gene (Figure 2A primer set 2) in 416B stable cell lines in experiments 5D. (F) Real-time PCR assay for PU.1 expression in 416B stable cell lines in experiments in panels D and E.

The interaction between MLL and AML1 is impaired by some mutant AML1 proteins found in leukemia patients. (A) Diagram of a series of the N-terminal frame shift and misssense mutations. The black bar indicates the MID. The black area indicates the Runt-domain. The black x's indicate missense mutation of AML1 found in MID (details in Figure 5C). (B) The AML1 frame shift mutants interact with MLL and block the interaction between wild-type AML1 and MLL. Lane 1, transfection control; lane 2, AML1 with vector control; lane3, AML1 with AML1 (1-57); lane 4, AML1 with AML1 (1-72); lane 5, AML1 with AML 1(1-91); and lane 6, AML1 with AML1 (1-105). Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-Flag; row 3, IP with anti-Flag, running with 10% SDS-PAGE gel and IB with anti-AML1; and row 4, IP with anti-Flag, running with 20% SDS-PAGE gel and IB with anti–AML1-N). (C) The N-terminal missense mutations of AML1 impair MLL interaction. Lane 1, transfection with pCS2 vector control and AML1; lane 2, MLL with AML1; lane 3, MLL with AML1 (L29S); lane 4, MLL with AML1 (A33V); lane 5, MLL with AML1 (G42R); lane 6, MLL with AML1 (R49H); lane 7, MLL with AML1 (R49S); lane 8, MLL with AML1 (H58N); lane 9, MLL with AML1 (V63A); lane 10, MLL with AML1 (S67I); and lane 11, MLL with AML1 (W79C). Western blots were done using indicated antibodies (row 1, anti-AML1; row 2, IP with anti-Flag and IB with anti-Flag; and row 3, IP with anti-Flag, IB with anti-AML1). (D) ChIP assay with anti-MLL antibodies and with primer set at 3′URE region of PU.1 gene (Figure 2A primer set 2) with 416B stable cell lines: 1, pBEX; 2, pBEX-AML1; 3, pBEX-AML1 (1-91); 4, pBEX-AML1 (1-105); 5, pBEX-AML1 (L29S); 6, pBEX-AML1 (H58N); 7, pBEX-AML1 (R139Q); and 8, pBEX-AML1 (R177Q). (E) ChIP assay with anti-H3K4me3 antibodies and with primer set at 3′URE region of PU.1 gene (Figure 2A primer set 2) in 416B stable cell lines in experiments 5D. (F) Real-time PCR assay for PU.1 expression in 416B stable cell lines in experiments in panels D and E.

We next addressed the regulatory function of these AML1 mutant proteins, and 2 DNA binding defective AML1 mutant proteins (R139Q and R177Q), on PU.1 expression using retroviral transduction to express AML1, (1-91) AML1, (1-105) AML1 (L29S), AML1 (H58N), AML1 (R139Q), or AML1 (R177Q) in 416B cells. Stably expressing GFP positive cell lines were established and used for ChIP and qPCR assays. Overexpression of AML1 increases MLL binding and H3K4me3 at the PU.1 URE region, and also PU.1 expression (Figure 5D-F lane 2). However, the frame shift mutants (AML1 [1-91] and AML1 [1-105]), missense mutants (AML1 [L29S] and AML1 [H58N]) and DNA binding mutants (AML1 [R139Q] and AML1 [R177Q]) all show less Mll and H3K4 trimethylation at the PU.1 URE (Figure 5D-E lanes 3-8). These mutants also have a minimal effect on PU.1 expression.

Discussion

We have shown that both MLL and AML1/CBFβ are required for maintaining the H3K4-me3 mark at the PU.1 upstream regulatory element (URE) and promoter region, and for full PU.1 gene expression. Furthermore, we demonstrate that MLL binds to a region of AML1 (that is conserved in AML2 and AML3) and increases AML1 (AML2 and AML3) protein levels. We examined MDS- or AML-associated AML1 mutations (frame-shift and missense mutations) that do not alter its DNA binding or CBFβ binding properties (except S67I, which is a CBFβ-interaction defective mutant) and found that they decrease the interaction between AML1 and MLL. Taken together, our data indicate that the physical and functional interaction of MLL with AML1 promotes AML1 target gene expression; disruption of this functional interaction by mutations that affect a component of this complex (MLL, AML1, or CBFβ) is a common event in MDS and AML.

Whole genome-wide studies of H3K4 methylation show that this mark is primarily localized in the promoter and regulatory regions of genes. H3K4 methylation may be an early histone modification that helps determine subsequent histone modifications, including acetylation and deacetylation.33 The cellular processes controlling the initiation, maintenance, and inheritance of the H3K4 methylation mark are still largely unknown, however, transcription factors have been suggested to play an important role in these processes and even in the inheritance of histone modification marks. The Menin, LEDGF, HCF1/2, E2F, NFE2, p53, and c-Myb transcription factors have been shown to interact with MLL family members, which could lead to methylation of H3K4.34-40

Here we show that AML1/CBFβ is required for maintaining H3K4 methylation in two regulatory regions of its target gene PU.1. The sequence specific DNA binding by AML1/CBFβ and recruitment of MLL may initiate H3K4 methylation at many of the AML1/CBFβ target genes. The initiation of target gene H3K4 methylation and subsequent gene expression might explain how AML1/CBFβ functions as a master regulator in hematopoiesis, and why AML1/CBFβ and MLL are frequently mutated in different patients with the same spectrum of diseases.

The Set1 family of methyltransferases methylate H3K4 and while a single gene (Set1) is responsible for this modification in yeast, 9 distinct proteins exist in higher eukaryotes that can regulate this modification. Other families of H3K4 methyltransferases also exist,41 but when we used shRNA against MLL, we found that its activity is required for the maintenance of the H3K4 mark at PU.1 regulatory regions. This suggests that MLL is the major methyltransferase, but it does not rule out the possibility that other methyltransferses might also be capable of initiating or maintaining the H3K4me3 mark at the AML1 target genes. Nonetheless, given the role that PU.1 dysregulation may play in human leukemogenesis,42 its role in B cell and monocyte differentiation and maturation, and the high frequency of MLL gene mutations in human leukemias of the B cell and monocytic lineages, it appears that MLL plays a significant role in regulating the H3K4 modification at the PU.1 locus in hematopoietic cells.

Although MLL increases AML1 levels in the absence or presence of CBFβ, the increased level of AML1 is more profound when CBFβ is also present (Figure 1B). Thus, the recruitment of wild-type MLL by AML1 is not only responsible for maintaining the H3K4me3 histone modification, but also for maintaining the level of AML1 protein in the cell. Our data suggest that MLL protects AML1 from ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. The MLL interaction domain in AML1 is at its amino terminus of the Runt-domain, a region that is highly conserved throughout evolution. The crystal structure of the amino terminus of the Runt domain of human AML1 shows an α-helix and a surface formed by several β-sheets and loops. Some missense mutations in AML1 found in patients with MDS or AML are located in the α-helical region, which should not affect DNA binding or the interaction of AML1 with CBFβ.43 We found that several of these missense mutant proteins (when intact for CBFβ binding and DNA binding) and S67I (which is also a CBFβ binding defective mutant) have lost the ability to interact with MLL. This suggests that the loss of MLL binding could lead to similar consequences as loss of DNA binding, loss of CBFβ binding or loss of transactivation function, thereby identifying a new mechanism for these loss of function AML1 mutations in leukemogenesis. Although certain frame shift mutations have been thought of as loss-of-function mutations,44 it is possible that these mutations could result in the expression of one or more peptides, such as AML1 (1-91) and AML (106-453), based on different methionine usage. Our data suggest that the naturally occurring splice variant, AML1ΔN, which contains the same amino acids as AML1 (106-453), could inhibit AML1 function by sequestering molecules that interact with the C-terminus of AML1.45 The N-terminal short AML1 peptide could also inhibit the interaction of wild-type AML1 with MLL, supporting the notion that MDS and AML-related AML1 mutations have dominant negative function.46 It is also possible that the broad effects of MLL in hematologic, skeletal, and neural development could be explained by the physical and functional interaction of MLL with AML1, AML2, and AML3.

It appears that MLL and CBFβ bind to different surfaces of AML1, forming a ternary complex or an even larger complex containing components of the MLL complex, the AML1/CBFB complex, and their various interacting proteins (such as MOZ/MORF, CBP/p300). Our data suggest that by binding MLL, AML1 might change its conformation possibly enhancing its interaction with CBFβ. The interaction of MLL might serve as a molecular switch for both CBFβ binding and DNA binding, as early studies show that amino acid residues both amino-terminal and carboxyl-terminal to the Runt-domain can negatively regulate CBFβ and DNA binding.47 The same effect could be true for the AML1 and CBFβ interaction, which could enhance the interaction of MLL with AML1/CBFβ. Nonetheless, the combinatorial interaction of these proteins could secure the high affinity binding of the AML1/CBFβ complex to DNA and recruitment of the MLL complex, which methylates the histone H3K4 mark, priming AML1/CBFβ target genes for further transcriptional regulation. Although some MID mutations appear to be loss-of-function mutants for AML1, other MID mutants show higher affinity for CBFβ than wild-type AML1 (data not shown), and this higher affinity could rescue their protein levels allowing them to function as dominant negative molecules capable of sequestering MLL away from the wild-type AML1/CBFβ complex.

In summary, MLL and AML1/CBFβ are critical for normal hematopoiesis, and frequently involved in human leukemia. We have demonstrated that they physically and functionally interact to maintain the histone H3K4-me3 mark at critical regulatory regions of an AML1 target gene, PU.1.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society SCOR grant (to S.D.N.), by an RO1 grant from the National Institutes of Health (DK52208 to S.D.N.), by an RO1 grant from the National Institutes of Health (CA41456 to D.G.T.), a Biomedical Research Council (BMRC) grant (to M.O.), and by the Maynard Parker Leukemia Research Fund at MSKCC.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: G.H. and S.D.N. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; D.G.T., M.O. and J.J.-D.H. contributed vital new reagents; and G.H., Xinghui Zhao, L.W., S.E., X.H., Xinyang Zhao, G.S., Y.Z., Y.L., J.L., S.M., Y.Y., X.Y., and P.Z. performed research and analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen D. Nimer, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, Box 575, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: s-nimer@mskcc.org; or Gang Huang, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Rm S7.607, MLC 7013, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039; e-mail: gang.huang@cchmc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal