Key Points

Runx factors are critical for HSC function, preventing HSC exhaustion by maintaining levels of PU.1.

Runx factors are required for leukemia survival by maintaining the stemness of leukemic cells through their downstream target PU.1.

Abstract

Runx transcription factors contribute to hematopoiesis and are frequently implicated in hematologic malignancies. All three Runx isoforms are expressed at the earliest stages of hematopoiesis; however, their function in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is not fully elucidated. Here, we show that Runx factors are essential in HSCs by driving the expression of the hematopoietic transcription factor PU.1. Mechanistically, by using a knockin mouse model in which all three Runx binding sites in the −14kb enhancer of PU.1 are disrupted, we observed failure to form chromosomal interactions between the PU.1 enhancer and its proximal promoter. Consequently, decreased PU.1 levels resulted in diminished long-term HSC function through HSC exhaustion, which could be rescued by reintroducing a PU.1 transgene. Similarly, in a mouse model of AML/ETO9a leukemia, disrupting the Runx binding sites resulted in decreased PU.1 levels. Leukemia onset was delayed, and limiting dilution transplantation experiments demonstrated functional loss of leukemia-initiating cells. This is surprising, because low PU.1 levels have been considered a hallmark of AML/ETO leukemia, as indicated in mouse models and as shown here in samples from leukemic patients. Our data demonstrate that Runx-dependent PU.1 chromatin interaction and transcription of PU.1 are essential for both normal and leukemia stem cells.

Introduction

As the DNA-binding subunit of the heterodimeric transcription factor core-binding factor (CBF), the three isoforms of the RUNX family, RUNX1 (AML1/CBFA2/PEBP2aB), RUNX2 (AML3/CBFA1/PEBP2aA), and RUNX3 (AML2/CBFA3/PEBP2aC), regulate normal cell specification during development and are commonly altered in many forms of leukemia and cancer (reviewed in Ito1 and Blyth et al2 ). Runx1 and CBFβ, the heterodimeric partner of all three Runx proteins, are the most frequent mutational targets in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). They are disrupted either by chromosomal translocations that create oncogenic fusion proteins such as AML1-ETO and CBFB-MYH11 or by intragenic loss-of-function mutations and loss of heterozygosity.3-7 In leukemia with chromosomal translocations, a dominant negative effect of the fusion protein and inactivation of the Runx downstream target PU.1 has been considered as a critical mechanism of leukemia development.8-15

Runx1 knockout mice lack definitive hematopoiesis,16 mainly because of the essential role of Runx1 in the endothelial-to-hematopoietic cell transition during embryonic development.17-20 However, studies of its function in adult hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have been inconsistent, with some demonstrating that Runx1 deficiency results in HSC defects21,22 and others suggesting minimal impact on HSCs.23,24 Partial and varying compensation by other Runx family members might explain the discrepancies of these reports, given that all 3 Runx family members bind directly to a conserved nucleotide sequence (-TGNGGTA-). Indeed, it was shown recently that Runx3 has an antiproliferative function in HSCs and/or progenitors of aged mice.25 In this report, using a knockin mouse model in which binding of all Runx factors at the −14kb upstream enhancer of PU.1 is abolished,11 we could rule out any compensatory effects of individual Runx family members. By using this model, we observed major importance of the Runx-PU.1 pathway for HSC function. Mechanistically, Runx binding facilitated chromosomal loop formation between the PU.1 enhancer and its proximal promoter, thereby promoting transcription. Importantly, we further found that Runx-induced PU.1 expression is essential for leukemic initiating cell (LIC) function in AML/ETO9a leukemia. These findings point to the importance of PU.1 in both normal and leukemia stem cells.

Methods

Mice

Generation of PU.1 upstream regulatory element (URE)-mRunx mice was previously reported.11 Supplemental Figure 1A (available on the Blood Web site) indicates the exact position of binding site mutations. Mx-1Cre conditional Runx1 knockout mice as well as transgenic mice with a human PU.1 bacterial artificial chromosome used in this study have been described previously.26,27 All mouse strains were crossed into C57B6 mice for at least 6 generations. Primer sequences for genotyping polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) are listed in supplemental Table 1. For all experiments, only 4-month-old littermates were used, which were generated by breeding of heterozygous mice. Mice were kept in a sterile barrier facility, and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental procedures.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry, we used the following monoclonal antibodies conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE), PE-CY7, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), allophycocyanin (APC), APC-Cy7, or eFluor 450 obtained from BD Pharmingen (BD), BioLegend (San Diego, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA): Mac-1/CD11b (M1/70), Gr-1 (8C5), CD3 (KT31.1), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD19 (1D3), TER119 (TER-119), Sca1 (E13-161-7), c-Kit (2B8), CD16/32 (2.4G3), Thy-1.2 (53-2.1), CD135 (AF2 10.1), CD48 (HM48-1), Ly5.1 (A20), Ly5.2 (104), and CD150 (TC15-12F12.2). Viable cells were identified either by propidium iodide or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole exclusion. Cells were analyzed by LSRII flow cytometer or sorted by FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For data acquisition and analysis, Diva software (BD) or FlowJo (Tree Star) was used.

Real-time PCR

Cells were sorted by flow cytometry directly into a tube containing 350 µL of a lysis buffer (Qiagen), and RNA was purified by using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). RNA was either directly used in TaqMan real-time PCR (RT-PCR) or reverse transcribed and subsequently amplified with a Rotor-Gene 6000 RT-PCR machine (Corbett). Transcript levels of tested genes were normalized to 18S (Applied Biosystems) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as indicated. Sequence information of primers and TaqMan probes are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Chromosome conformation capturing

Semiquantitative chromosome conformation capturing (3C) was performed as previously described with some modifications.28 Briefly, 5- to 6 × 105 cKit bone marrow cells were sorted from paired wild-type (WT) and Runx mutant mice. Cells were cross-linked, digested with Bgl2, and ligated as described.29 Control libraries were prepared with bacterial artificial chromosome DNA spanning the entire locus (gi: 31335567). Libraries were amplified for 27 cycles, followed by gel fractionation (2.5% agarose gel) and transferred to nylon filters. Filters were hybridized with T4 kinase-32P-labeled mixture of four composite oligonucleotides, 10 ng each (oligonucleotide and probe sequences are provided in supplemental Table 1). Hybridization and washing were performed with ULTRAhyb-Oligo (Ambion, Cat. No. 8663) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Quantitative analysis was performed by using a Storm Phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

Quantitative TaqMan RT-PCR–based 3C analysis was performed as described previously.30 A TaqMan probe was designed for the H2 fragment of the −14kb URE containing the PU.1 autoregulatory site. We used an amplicon within two Bgl2 restriction sites in intron 3 of the PU.1 gene as a housekeeping gene. Sequence information for all primers and probes used is shown in supplemental Table 1. 3C experiments were performed as 2 independent biological and two technical replicates.

Transplantations

For limiting dilution competitive repopulation unit assays, HSCs were collected from CD45.2+ mice (WT and PU.1-URE-mRunx), indicated number of cells were re-sorted into individual wells of a 96-well plate containing 2 × 105 CD45.1+ whole bone marrow cells in phosphate-buffered saline, and transplanted intravenously into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients (650 rads twice with a 4-hour rest interval). Peripheral blood and bone marrow were obtained from each mouse after 6 months and were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Recipient mice with less than 0.3% chimerism (CD45.2+CD45.1–) in lymphomyeloid lineage were considered as negative responders. Serial and mixed bone marrow competitive transplantations were performed as described in the figure legends.

The transduction of E14.5 fetal liver cells (WT and PU.1-URE-mRunx) was performed after lineage depletion with the retroviral MigR1 vector expressing AML/ETO9a (MigR1-A/E9a).31 After 48 hours, equal amounts (104) of green fluorescence protein (GFP+) cells were transplanted into irradiated (650 rads) CD45.1+ recipients. Limiting dilution LIC assay was performed using WT + A/E9a and PU.1-URE-mRunx + A/E9a leukemic cells from primary recipients transplanted at indicated cell numbers into irradiated (650 rads) CD45.1+ recipients.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were done on total bone marrow cells (2 × 106 cells per ChIP assay) using polyclonal rabbit antibody to Runx (CST #4334), as described previously.30

Statistical analysis

L-Calc software (StemCell Technologies) was used to calculate competitive repopulation unit and LIC frequencies. The statistical differences in frequencies between sets of limiting dilution analyses were assessed on the basis of the asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimates and were calculated by using the χ2 test. For survival studies (5-fluorouracil [5-FU] transplantations of A/E9a-transduced fetal liver cells), a log-rank nonparametric test (Mantel-Cox) was used. Student unpaired t test was used for all other experiments, and statistical significance was indicated as P < .05 and P < .01. Gaussian error propagation was applied for normalized data.

Results

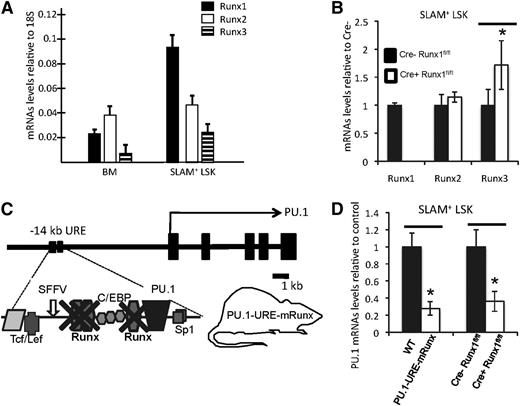

Runx binding sites in the PU.1 URE mediate PU.1 transcription in HSCs

In order to understand the role of the 3 Runx factors in regulating PU.1 in hematopoietic stem cells, we first evaluated expression of the 3 Runx transcription factors in unselected bone marrow cells and HSCs (SLAM+ LSK, or lineage-Sca1+cKit+CD150+CD48– 32 ). Although expression of all Runx genes was clearly detectable in both populations, Runx1 was the most highly expressed factor in HSCs (Figure 1A) (note that expression data for Runx1 have been presented in Levantini et al,33 see supplemental Figure 1). To test whether loss of Runx1 would result in a compensatory upregulation of either Runx2 or Runx3 in HSCs, we used Mx1-Cre1 inducible Runx1 knockout mice26 and tested changes in messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of individual Runx factors. Induced disruption of Runx1 resulted in nondetectable Runx1 mRNA levels in HSCs, indicating efficient excision. Interestingly, Runx3 levels were significantly increased, whereas Runx2 levels remained unchanged, suggesting that Runx3 might partially compensate for Runx1 loss in HSCs (Figure 1B).

Runx factors mediate PU.1 transcription in HSCs through binding sites at the −14kb URE. (A) mRNA levels of indicated Runx genes in unselected whole bone marrow (BM) cells and isolated SLAM+ LSK cells (HSC-enriched population). Shown are average levels + standard deviation (SD); n = 7 (B) mRNA levels of indicated Runx genes after CRE-induced Runx1 deletion in SLAM+ LSK cells. Shown are average levels ± SD. n = 4; *P < .05. (C) Simplified scheme of murine PU.1 locus indicating the 3 Runx binding sites, all of which have been selectively mutated from TGTGGTA to TGACCTA in the knockin mouse model PU.1-URE-mRunx. (D) PU.1 mRNA levels in SLAM+ LSK cells of PU.1-URE-mRunx and Runx1-deleted mice compared with control. Shown are average levels ± SD. n = 4; *P < .05.

Runx factors mediate PU.1 transcription in HSCs through binding sites at the −14kb URE. (A) mRNA levels of indicated Runx genes in unselected whole bone marrow (BM) cells and isolated SLAM+ LSK cells (HSC-enriched population). Shown are average levels + standard deviation (SD); n = 7 (B) mRNA levels of indicated Runx genes after CRE-induced Runx1 deletion in SLAM+ LSK cells. Shown are average levels ± SD. n = 4; *P < .05. (C) Simplified scheme of murine PU.1 locus indicating the 3 Runx binding sites, all of which have been selectively mutated from TGTGGTA to TGACCTA in the knockin mouse model PU.1-URE-mRunx. (D) PU.1 mRNA levels in SLAM+ LSK cells of PU.1-URE-mRunx and Runx1-deleted mice compared with control. Shown are average levels ± SD. n = 4; *P < .05.

The hematopoietic transcription factor PU.1 harbors 3 conserved Runx binding sites at its −14kb URE (supplemental Figure 1A).11 Reporter assays in stably transfected 416B cells demonstrated that the transcriptional activation potency of the URE depends highly on the intactness of all 3 Runx binding sites (supplemental Figure 1B and Huang et al11 ). We previously generated a knockin mouse model (PU.1-URE-mRunx) in which binding of all Runx factors was abolished from the URE of PU.111 (Figure 1C). Electromobility shift assays demonstrated that, in contrast to a loss of all 3 URE Runx binding sites, a loss of Runx1 alone led to only a minimal decrease of CBF binding because of the contribution of other Runx family members.11 ChIP analyses of total bone marrow cells confirmed the loss of Runx binding to the −14kb URE in PU.1-URE-mRunx mice (supplemental Figure 1C). Importantly, PU.1 mRNA levels in HSCs of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice were reduced by 72% in comparison with controls (WT), greater than the average reduction of 63% observed in Runx1 knockout mice (Figure 1D). These results revealed the major role of the URE Runx sites for PU.1 transcription in HSCs.

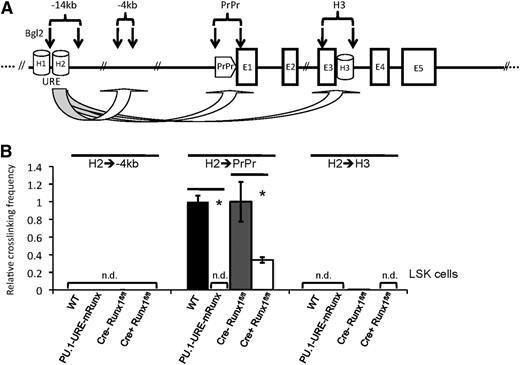

Disruption of Runx binding leads to a loss of URE-proximal promoter interaction

We recently reported that a stable interaction of the URE with the proximal promoter is required for efficient PU.1 transcription in hematopoietic progenitors and/or HSCs.30 To test whether Runx binding is also necessary for loop formation in the PU.1 gene locus, we designed a 3C experiment in which, after DNA crosslinking and restriction enzyme digestion (with Bgl2), the frequency of interactions of the URE with other DNA fragments was quantified by TaqMan RT-PCR (Figure 2A). In LSK (lin–, sca+, cKit+) stem and/or progenitor cells, induced deletion of Runx1 resulted in a pronounced (66%) decrease in crosslinking frequency between the URE and proximal promoter. After disruption of Runx binding sites, however, crosslinking frequencies were not detectable (Figure 2B). To verify the dramatic effect of URE Runx site mutations on PU.1 folding, we also applied a semiquantitative (PCR/Southern blot–based) 3C approach investigating the interactions of the proximal promoter with other DNA segments in the PU.1 locus (supplemental Figure 2A). By using isolated cKit+ cells from bone marrows of PU.1-URE-mRunx and WT mice, we could confirm the loss of interaction between URE and proximal promoter following Runx site mutation (supplemental Figure 2B).

Runx site mutation leads to loss of URE-proximal promoter interaction in HSCs and/or progenitors. (A) Simplified scheme of the PU.1 gene indicating the positions of homology regions (H1-H3), the −14kb URE, proximal promoter (PrPr), exon 1 through exon 5 (E1-E5), and Bgl2 restriction sites (vertical arrows) for quantitative 3C. The genomic region at −4kb was used as control. (B) Quantitative 3C demonstrates a loss of URE-PrPr interaction in mice with disrupted Runx binding sites (PU.1-URE-mRunx) and a significant loss after induced Runx1 deletion in LSK cells. After crosslinking and Bgl2 digestion, ligated DNA was purified, and interactions of the H2 region with indicated genetic locations was measured by TaqMan PCR and calibrated with an intergenetic DNA amplicon. Graphs represent the results of 4 independent quantitative TaqMan PCR experiments (average + SD; *P < .05). Crosslinking efficiencies are shown as relative values to H2-PrPr interactions of WT and Cre-Runx1fl/fl, respectively. n.d., not detectable.

Runx site mutation leads to loss of URE-proximal promoter interaction in HSCs and/or progenitors. (A) Simplified scheme of the PU.1 gene indicating the positions of homology regions (H1-H3), the −14kb URE, proximal promoter (PrPr), exon 1 through exon 5 (E1-E5), and Bgl2 restriction sites (vertical arrows) for quantitative 3C. The genomic region at −4kb was used as control. (B) Quantitative 3C demonstrates a loss of URE-PrPr interaction in mice with disrupted Runx binding sites (PU.1-URE-mRunx) and a significant loss after induced Runx1 deletion in LSK cells. After crosslinking and Bgl2 digestion, ligated DNA was purified, and interactions of the H2 region with indicated genetic locations was measured by TaqMan PCR and calibrated with an intergenetic DNA amplicon. Graphs represent the results of 4 independent quantitative TaqMan PCR experiments (average + SD; *P < .05). Crosslinking efficiencies are shown as relative values to H2-PrPr interactions of WT and Cre-Runx1fl/fl, respectively. n.d., not detectable.

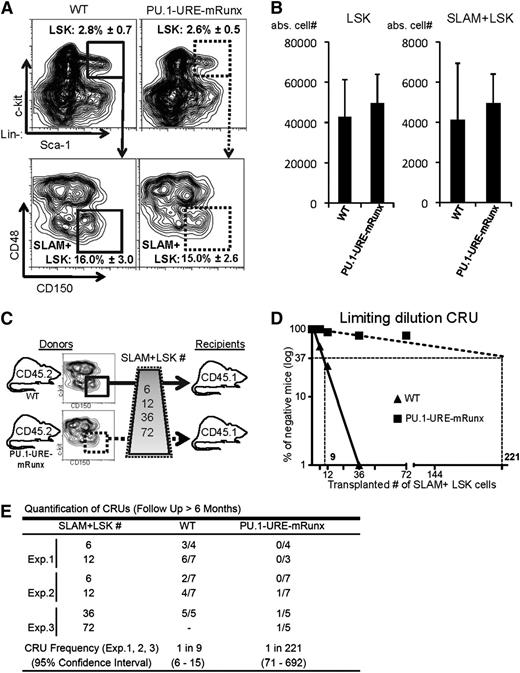

Mutation of the Runx binding sites results in loss of HSC function

Because PU.1-URE-mRunx mice expressed PU.1 at very low levels in HSCs, we next analyzed the HSC phenotype. The percentage of progenitors (LSKs) and HSCs in PU.1-URE-mRunx mice was not different from that in WT controls as determined at an age of 4 months (Figure 3A). Similarly, absolute cell numbers of LSKs and HSCs also appeared to be unchanged (Figure 3B). HSCs of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice demonstrated normal bone marrow homing capabilities (supplemental Figure 3). To test whether the Runx-PU.1 axis would have an impact on the function of HSCs, we performed competitive repopulation transplantation with limiting dilution of phenotypic HSCs (Figure 3C). After 6 months, we evaluated hematopoietic reconstitution in blood and bone marrow considering mice with a CD45.2 chimerism of <0.3% as negative responders. Quantification of competitive repopulating units showed a severe (24.5-fold) decrease, indicating a dramatic loss of HSC long-term function (Figure 3D-E).

Runx binding site mutation leads to reduced numbers of functional HSCs. (A-B) Phenotypic HSCs are unaltered in PU.1-URE-mRunx mice compared with WT (4 months). (A) Flow cytometry of bone marrow samples demonstrating the average percentage ± SD of LSK cells (from lineage-negative population) and the average percentage ± SD of SLAM+ LSK cells (from LSK population). (B) Total number of LSK and SLAM+ LSK cells in bone marrow (average + SD of 1 femur and 1 tibia; n = 5). (C) Experimental scheme of the limiting dilution competitive repopulation unit (CRU) assay. Indicted numbers of isolated SLAM+ LSK cells of WT or PU.1-URE-mRunx mice (CD45.2) were transplanted together with 2 × 105 unselected whole bone marrow cells of competitor mice (CD45.1) into lethally irradiated (1300 rads) recipients (CD45.1). (D) Semilogarithmic plot showing the percentage of negative recipients as a function of the number of transplanted SLAM+ LSKs. CRUs are indicated as vertical dashed lines. (E) Table showing the frequency of CRUs and the total number of transplantations per cell dose. Reconstitution was evaluated in blood and bone marrow 6 months after transplantation. Mice with CD45.2 chimerism <0.3% were considered as nonresponders. abs., absolute; Exp., experiment.

Runx binding site mutation leads to reduced numbers of functional HSCs. (A-B) Phenotypic HSCs are unaltered in PU.1-URE-mRunx mice compared with WT (4 months). (A) Flow cytometry of bone marrow samples demonstrating the average percentage ± SD of LSK cells (from lineage-negative population) and the average percentage ± SD of SLAM+ LSK cells (from LSK population). (B) Total number of LSK and SLAM+ LSK cells in bone marrow (average + SD of 1 femur and 1 tibia; n = 5). (C) Experimental scheme of the limiting dilution competitive repopulation unit (CRU) assay. Indicted numbers of isolated SLAM+ LSK cells of WT or PU.1-URE-mRunx mice (CD45.2) were transplanted together with 2 × 105 unselected whole bone marrow cells of competitor mice (CD45.1) into lethally irradiated (1300 rads) recipients (CD45.1). (D) Semilogarithmic plot showing the percentage of negative recipients as a function of the number of transplanted SLAM+ LSKs. CRUs are indicated as vertical dashed lines. (E) Table showing the frequency of CRUs and the total number of transplantations per cell dose. Reconstitution was evaluated in blood and bone marrow 6 months after transplantation. Mice with CD45.2 chimerism <0.3% were considered as nonresponders. abs., absolute; Exp., experiment.

To further analyze whether the loss of functional HSCs of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice was related to premature HSC exhaustion, we performed a series of analyses on HSCs after repetitive injuries and stress. We first evaluated their capability to regenerate bone marrow after repetitive injections with the antimetabolite 5-FU. Survival of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice was significantly decreased (P < .0001) upon once-per-week 5-FU injections, demonstrating that HSCs of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice could not provide sufficient blood supply after injuries, a key physiologic task of HSCs (Figure 4A). By using repetitive transplantation experiments, we investigated whether the ability to repopulate bone marrow decreased with increasing rounds of transplantation as a result of stem cell exhaustion. Indeed, HSCs of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice failed to repopulate bone marrows of lethally irradiated recipients after the third round of transplantations (Figure 4B). To confirm the results of limiting dilution competitive repopulation experiments with isolated SLAM+ LSK cells, we performed competitive long-term repopulation assays with total bone marrow cells. These results also demonstrated marked functional defects in HSCs of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice, thus indicating that the HSC defect was independent of the surface markers used to characterize SLAM+ LSK cells (Figure 4C). We previously demonstrated that crossing a human PU.1 transgenic strain with PU.1 knockout, PU.1 heterozygous, and PU.1 hypomorphic mice could restore PU.1 protein levels.27,30 Importantly, we here show that HSC functions of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice could be rescued by the human PU.1 transgene (Figure 4C), thus providing proof that the HSC phenotype of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice depends on PU.1.

Long-term HSC deficiency of Runx site mutants is related to exhaustion and is PU.1 dependent. (A) Reduced capability of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice to regenerate bone marrow after repetitive injuries by weekly administration of 5-FU 150 mg/kg injected intraperitoneally. Results are shown as Kaplan-Meier survival curves (n = 9; P < .0001 [Mantel-Cox]). (B) Serial transplantation assays. Rounds of transplantations with 5 × 105 bone marrow cells were performed at 16-week intervals. Bar graphs indicate survival percentage after each round of transplantation (TX) (n = 5). (C) Whole bone marrow cells (1 × 106) of indicated donor mice (CD45.2+) were co-transplanted with equal amounts of CD45.1+ WT bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. Bar graphs show donor chimerism in blood after 6 months (average + SD; n = 5; **P < .01). Loss of chimerism of PU.1-URE-mRunx donors was restored by breeding to a strain harboring a human transgene expressing PU.1 (+hPU.1-TG).

Long-term HSC deficiency of Runx site mutants is related to exhaustion and is PU.1 dependent. (A) Reduced capability of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice to regenerate bone marrow after repetitive injuries by weekly administration of 5-FU 150 mg/kg injected intraperitoneally. Results are shown as Kaplan-Meier survival curves (n = 9; P < .0001 [Mantel-Cox]). (B) Serial transplantation assays. Rounds of transplantations with 5 × 105 bone marrow cells were performed at 16-week intervals. Bar graphs indicate survival percentage after each round of transplantation (TX) (n = 5). (C) Whole bone marrow cells (1 × 106) of indicated donor mice (CD45.2+) were co-transplanted with equal amounts of CD45.1+ WT bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. Bar graphs show donor chimerism in blood after 6 months (average + SD; n = 5; **P < .01). Loss of chimerism of PU.1-URE-mRunx donors was restored by breeding to a strain harboring a human transgene expressing PU.1 (+hPU.1-TG).

Delayed AML/ETO9a leukemia onset in cells of Runx binding site mutants

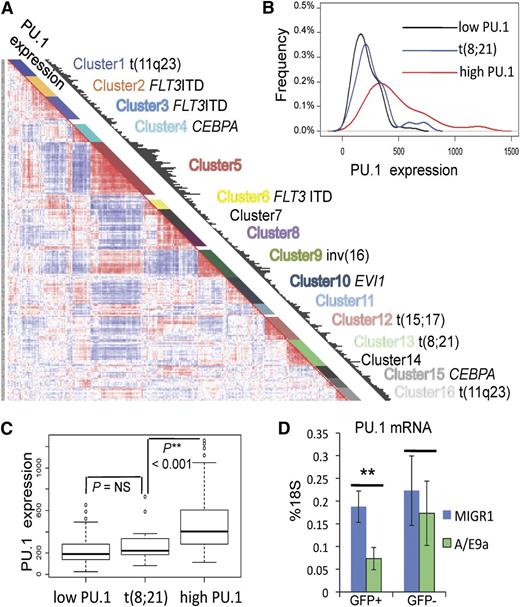

We next aimed to investigate whether leukemic stem cells share the same dependence on the Runx-PU.1 pathway as normal HSCs. Given the role of Runx in regulating PU.1,11 and other studies suggesting that dysregulation of PU.1 is an important mechanism in some types of AML,8,34-36 we chose to test this hypothesis in a model of leukemia with low and/or dysfunctional PU.1. We first evaluated the relative PU.1 expression in leukemia patients by using the gene expression data set (Affymetrix U133A GeneChips) of the Erasmus Rotterdam cohort comprising 285 well-characterized patients with AML.37 PU.1 expression is shown as black bars in respect to hierarchical clusters that reflect distinct genetic abnormalities (Figure 5A). In this data set, all specimens from patients with the t(8;21) that generates the AML/ETO fusion gene grouped within cluster 1337 (Figure 5A). Using the global cluster mean expression of PU.1 as the cutoff, low PU.1 (132 patients) and high PU.1 (118 patients) clusters were defined, and their PU.1 expression profiles were compared with cluster t(8;21) (22 patients) (Figure 5B). The t(8;21) cluster was indistinguishable from the low PU.1 group, but it was significantly different from the high PU.1 group (Figure 5C). We then asked whether the expression of AML/ETO is responsible for PU.1 suppression. A truncated form of the AML/ETO fusion protein (AML/ETO9a) efficiently induces leukemia when expressed in an MigR1 retrovirus in fetal liver cells.31 Here we show that transducing E14.5 fetal liver cells with AML/ETO9a-MigR1 resulted in significantly reduced PU.1 mRNA levels compared with controls transduced with empty MigR1 vector (Figure 5D). Thus, AML/ETO leukemia represents low PU.1 leukemia, and decreased PU.1 levels are related to AML/ETO or AML/ETO9a expression.

Reduced PU.1 gene expression in human AML/ETO leukemia. (A) PU.1 expression (black bars) with respect to hierarchical clustering of the gene expression data set of 285 AML patients from the Erasmus Rotterdam cohort (Affymetrix U133A GeneChips).36 Each cluster demonstrates distinct genetic abnormalities as indicated. (B-C) PU.1 expression profile of cluster t(8;21) compared with low PU.1 and high PU.1 clusters. Red line: all clusters with cluster mean expression higher than the global cluster mean (high PU.1), including clusters 1, 2, 5, 9, 11, and 16 with 118 patients; black line: all clusters with cluster mean expression lower than the global cluster mean (low PU.1), including clusters 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 15 with 132 patients; blue line: cluster 13: t(8;21) with 22 patients. (D) PU.1 mRNA levels of E14.5 fetal liver cells (c-kit+, GFP+c-kit+, GFP–) 48 hours after transduction with either MigR1 or AML/ETO9a-MigR1 (A/E9a). Shown are average levels ± SD as percentage of 18S. n = 4; **P < .01.

Reduced PU.1 gene expression in human AML/ETO leukemia. (A) PU.1 expression (black bars) with respect to hierarchical clustering of the gene expression data set of 285 AML patients from the Erasmus Rotterdam cohort (Affymetrix U133A GeneChips).36 Each cluster demonstrates distinct genetic abnormalities as indicated. (B-C) PU.1 expression profile of cluster t(8;21) compared with low PU.1 and high PU.1 clusters. Red line: all clusters with cluster mean expression higher than the global cluster mean (high PU.1), including clusters 1, 2, 5, 9, 11, and 16 with 118 patients; black line: all clusters with cluster mean expression lower than the global cluster mean (low PU.1), including clusters 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 15 with 132 patients; blue line: cluster 13: t(8;21) with 22 patients. (D) PU.1 mRNA levels of E14.5 fetal liver cells (c-kit+, GFP+c-kit+, GFP–) 48 hours after transduction with either MigR1 or AML/ETO9a-MigR1 (A/E9a). Shown are average levels ± SD as percentage of 18S. n = 4; **P < .01.

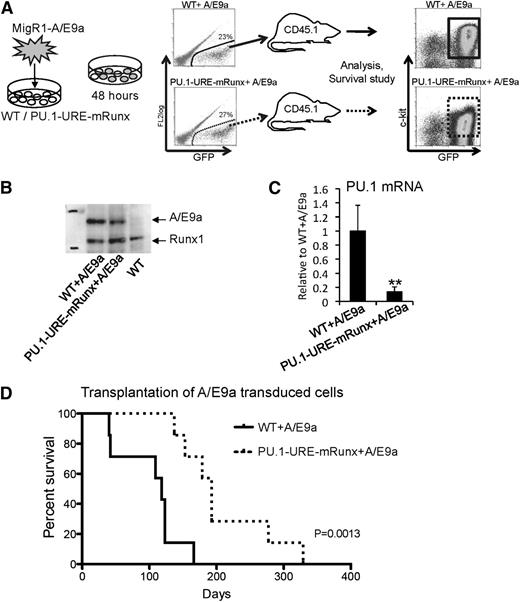

To test whether Runx-mediated PU.1 expression, even in a low-PU.1 leukemia model, is required for leukemic stem cell function, we transplanted equal numbers of AML/ETO9a-transduced E14.5 fetal liver cells of PU.1-URE-mRunx and WT mice (supplemental Figure 4A) into CD45.2 recipients and analyzed leukemia development and survival (Figure 6A). AML/ETO9a protein was stably expressed in samples from leukemic recipients (Figure 6B). Similar to HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice (supplemental Figure 4B), leukemic cells derived from AML/ETO9a-transduced PU.1-URE-mRunx cells also showed significantly decreased PU.1 levels compared with those derived from AML/ETO9a-transduced WT leukemia cells (Figure 6C). All recipients eventually developed leukemia with similar patterns of multiorgan infiltration (supplemental Figure 6). However, disease onset in recipients of AML/ETO9a-induced PU.1-URE-mRunx leukemic cells was delayed, and survival was significantly longer than that of recipients of AML/ETO9a-induced WT cells (median, 193 vs 118 days; P = .0013) (Figure 6D). A multistage process was reported for the erythroleukemia developed by spi-1/PU.1 transgenic mice,38 which is characterized by an early arrest of the proerythroblast differentiation followed later on (after 4 months) by malignant transformation with acquired mutations in exon 17 of the stem cell factor receptor gene (c-KIT) in 86% of tumors.39 In mRunx + A/E9a leukemia, c-kit expression appeared to be slightly reduced (Figure 6A and supplemental Figure 5); however, sequencing of genomic DNA of 6 WT + A/E9a and 6 PU.1-URE-mRunx tumors (primary transplants) at exon 17 of KIT did not reveal KIT mutations (data not shown; primer sequences are available in supplemental Table 1).

Mutation of Runx binding site leads to delayed onset of AML/ETO9a leukemia. (A) Experimental scheme: E14.5 fetal liver cells (lineage depleted) of PU.1-URE-mRunx and WT mice were retrovirally (MigR1) transduced with the fusion oncogene AML/ETO9a (A/E9a) harboring an eGFP signal. After 48 hours, GFP+ cells were isolated and transplanted into CD45.2 recipient mice (n = 7). Development of leukemia and survival were monitored. Moribund mice were taken for analysis. (B) Representative immunoblot demonstrating stable A/E9a protein expression in leukemic samples (spleen) of A/E9a recipients. (C) PU.1 mRNA levels of leukemic (c-kit+, GFP+) cells. Shown are average levels ± SD relative to WT + A/E9a. n = 4; **P < .01. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of recipients receiving either WT or PU.1-URE-mRunx cells transduced with A/E9a (n = 7; P = .0013).

Mutation of Runx binding site leads to delayed onset of AML/ETO9a leukemia. (A) Experimental scheme: E14.5 fetal liver cells (lineage depleted) of PU.1-URE-mRunx and WT mice were retrovirally (MigR1) transduced with the fusion oncogene AML/ETO9a (A/E9a) harboring an eGFP signal. After 48 hours, GFP+ cells were isolated and transplanted into CD45.2 recipient mice (n = 7). Development of leukemia and survival were monitored. Moribund mice were taken for analysis. (B) Representative immunoblot demonstrating stable A/E9a protein expression in leukemic samples (spleen) of A/E9a recipients. (C) PU.1 mRNA levels of leukemic (c-kit+, GFP+) cells. Shown are average levels ± SD relative to WT + A/E9a. n = 4; **P < .01. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of recipients receiving either WT or PU.1-URE-mRunx cells transduced with A/E9a (n = 7; P = .0013).

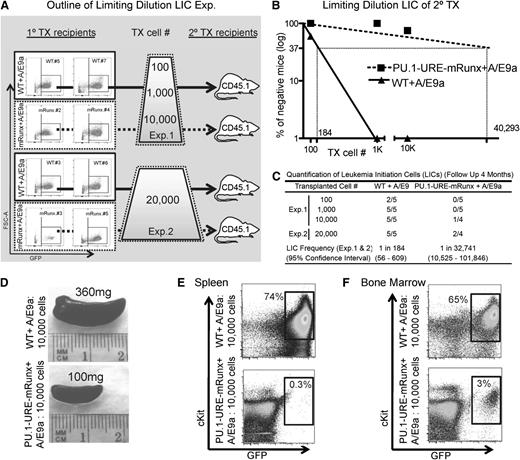

Loss of AML/ETO9a leukemic stem cells in Runx site mutants

The observed differences in disease latency might be related to different proliferation characteristics or to a different amount of LICs between the two groups. To investigate whether the observed delay of leukemia onset was related to a decreased number of functional leukemic stem cells that could initiate leukemia in AML/ETO9a PU.1-URE-mRunx recipients, we designed experiments to quantify LICs by using limiting dilution transplantations (Figure 7A). 100, 1000, 10 000, or 20 000 leukemic cells from primary recipients (AML/ETO9a-transformed WT and PU.1-URE-mRunx) were transplanted into secondary recipients (CD45.2+) respectively, and development of leukemia was monitored with a follow-up of up to 4 months. The characteristics of tumors used for transplantation experiments are indicated in Figure 7A and supplemental Figure 5. The LIC frequency of PU.1-URE-mRunx AML/ETO9a leukemias was dramatically decreased (1 in 32 741 compared with WT AML/ETO9a; 1 in 184; P < .0001) (Figure 7B-C). Leukemia was evident with splenomegaly (Figure 7D), and leukemic cell (c-Kit+ and GFP+) infiltration of spleen (Figure 7E) and bone marrow (Figure 7F). Thus, as for normal HSCs, the Runx-PU.1 pathway is essential for leukemic stem cell function of AML/ETO9a leukemia.

Runx site mutation loss of AML/ETO9a leukemic stem cells. (A) Experimental outline: WT + A/E9a and PU.1-URE-mRunx + A/E9a leukemic cells from moribund primary recipients (see Figure 6 and supplemental Figure 5) were isolated and transplanted as indicated in limiting dilutions to secondary recipients in which development of leukemia was monitored. (B) Logarithmic plot showing the percentage of negative recipients as a function of the dose of transplanted A/E9a leukemia cells. LICs were calculated as for CRUs. (C) Table showing the frequency of LICs and the total number of transplantations per cell dose. Leukemia development was monitored by survival and evaluated in spleen and bone marrow. No GFP+ cells were detectable in bone marrow or spleen of surviving mice after 4 months, which were then considered as nonresponders. (D) Representative picture of a leukemic (WT + A/E9a) and a nonleukemic (PU.1-URE-mRunx + A/E9a) spleen at 4 weeks after transplantation. (E-F) Flow cytometry analysis of spleens shown in (D) and corresponding bone marrows.

Runx site mutation loss of AML/ETO9a leukemic stem cells. (A) Experimental outline: WT + A/E9a and PU.1-URE-mRunx + A/E9a leukemic cells from moribund primary recipients (see Figure 6 and supplemental Figure 5) were isolated and transplanted as indicated in limiting dilutions to secondary recipients in which development of leukemia was monitored. (B) Logarithmic plot showing the percentage of negative recipients as a function of the dose of transplanted A/E9a leukemia cells. LICs were calculated as for CRUs. (C) Table showing the frequency of LICs and the total number of transplantations per cell dose. Leukemia development was monitored by survival and evaluated in spleen and bone marrow. No GFP+ cells were detectable in bone marrow or spleen of surviving mice after 4 months, which were then considered as nonresponders. (D) Representative picture of a leukemic (WT + A/E9a) and a nonleukemic (PU.1-URE-mRunx + A/E9a) spleen at 4 weeks after transplantation. (E-F) Flow cytometry analysis of spleens shown in (D) and corresponding bone marrows.

Discussion

This study uncovers a novel role of the Runx-PU.1 pathway in normal and leukemic stem cell biology. Previous reports of Runx1 function in HSCs have been inconsistent, probably due to partial compensatory effects of other Runx family members.21-24 Here we show that Runx1 deletion led to Runx3 upregulation in HSCs. Our data together with data from a recent study demonstrating a functional role of Runx3 in HSCs25 suggests that Runx3 partially substitutes for Runx1 function. The functional redundancy of Runx factors was further supported by a report showing Runx2 upregulation in MLL-AF9 leukemia.40 By disrupting the common binding sequences of all Runx family members in the PU.1 URE, we could evaluate the Runx-PU.1 axis without compensatory effects. We found that Runx factors mediate folding of the PU.1 locus to a loop formation and induce PU.1 transcription in HSCs, which is fundamental to preserving HSC function by preventing exhaustion. By using PU.1 hypomorphic mice, we recently provided experimental evidence that PU.1 prevents HSC exhaustion.30 In HSCs, PU.1 directly regulates various components of the cell cycle machinery by inhibiting cell cycle–promoting factors (eg, Cdk1, E2f1, and Cdc25a) and inducing the expression of inhibitors (eg, Cdkn1a (p21), Cdkn1c (p57), and Gfi1).30 Similarly, PU.1 slows down the cell cycle of HSCs and/or progenitors.41 Thus, our data provide functional evidence that by inducing PU.1, Runx factors prevent HSC exhaustion through the regulatory function of PU.1 on the cell cycle machinery.

Acute leukemia is characterized by a block in hematopoietic differentiation. Since PU.1 strongly promotes myeloid differentiation, it has been thought to be a leukemia-suppressive gene.42 Reducing PU.1 levels can induce AML in mice,34 and low PU.1 levels have also been implicated mechanistically in specific forms of leukemia such as acute promyelocytic leukemia43,44 and core-binding factor leukemia (Figure 5A-C).8-11,14 However, the observation that the Runx-PU.1 pathway is essential in HSC biology led us to investigate whether normal and leukemic stem cells might share the requirement of Runx-induced PU.1 for their stemness. As proof of principle, we disrupted the Runx-PU.1 axis in AML/ETO9a-induced leukemia and observed a dramatic decrease in leukemic stem cell function. This finding demonstrates the requirement of Runx-PU.1 for leukemic stem cell function, likely through the requirement of at least some level of PU.1 to prevent stem cell exhaustion. By using a mouse model with the combined loss of Runx1 and CBFB, a recent study reported the requirement of Runx for the survival of MLL-AF9 fusion leukemia cells.45 Another recent report indicated a key role of Runx1 in MLL-AF4 leukemia.46 Our data are consistent with these reports. Furthermore, we here present experimental evidence that Runx factors are required to maintain the stemness of leukemic cells through their downstream target PU.1.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frank Rosenbauer for providing human PU.1 transgenic mice27 and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) Flow Cytometry Facility.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01HL112719 and by the Singapore Ministry of Health National Medical Research Council under its Singapore Translational Research (STaR) Investigator Award (D.G.T.). P.B.S. received a fellowship from the Austrian Academy of Science (APART Stipendium 11379) and a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship from the European Union (PIOF-254486). C.B. was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG fellowship BA 4186/1-1).

Authorship

Contribution: P.B.S. designed the research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; P.Z., M.Y., R.S.W., E.L., A.D.R., A.K.E., C.B., H.Z., J.Z., H.Y., K.V., R.D., and G.H. performed research and analyzed data; and D.G.T. supervised the research, analyzed data, and contributed to writing the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel G. Tenen, 3 Blackfan Circle, Room 437, Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: daniel.tenen@nus.edu.sg; and Philipp B. Staber, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Department of Medicine I, Division of Hematology & Hemostaseology, Medical University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; email: philipp.staber@meduniwien.ac.at.

![Figure 4. Long-term HSC deficiency of Runx site mutants is related to exhaustion and is PU.1 dependent. (A) Reduced capability of PU.1-URE-mRunx mice to regenerate bone marrow after repetitive injuries by weekly administration of 5-FU 150 mg/kg injected intraperitoneally. Results are shown as Kaplan-Meier survival curves (n = 9; P < .0001 [Mantel-Cox]). (B) Serial transplantation assays. Rounds of transplantations with 5 × 105 bone marrow cells were performed at 16-week intervals. Bar graphs indicate survival percentage after each round of transplantation (TX) (n = 5). (C) Whole bone marrow cells (1 × 106) of indicated donor mice (CD45.2+) were co-transplanted with equal amounts of CD45.1+ WT bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. Bar graphs show donor chimerism in blood after 6 months (average + SD; n = 5; **P < .01). Loss of chimerism of PU.1-URE-mRunx donors was restored by breeding to a strain harboring a human transgene expressing PU.1 (+hPU.1-TG).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/15/10.1182_blood-2014-01-550855/4/m_2391f4.jpeg?Expires=1765893444&Signature=P0gH0lISKhsb-Qk9OoDpB7bDEhT5T4jcZzRuVHr0rKa17D4zyxFVQ0UQk1XqirG6fachHO0HWNRMRN5Zala-FWhiO4vJySwsRRa~r~Fs79lCsy1iaIGsjlTcyOHzvsCSidgeAUlAvV6PX72Afmhli2czcJun7duMqc-3b5tIg6IhH34EVBo1J-feO3Zlw67roRvlQbID~E~N6OjCkpVCVXO3uVK-ujEm7NIo5is1U5dAE42Tg9JM-t~-S6Fx9Y8yZJuhjGeoiVsVZ2CXmozcYovhSUfuRuKMy8XG1ROHi4yO7hArhMtcL5xGxz5JhMESgMP8StCH~WpWXDD5mAcETw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)