TO THE EDITOR:

BCR-ABL-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of clonal stem cell disorders characterized by the overproduction of mature myeloid cells. However, MPN patients also have a 2.8- to 3.4-fold increased risk of developing a lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) compared with the general population.1,2 A range of lymphoid neoplasms have been documented in MPN patients, most commonly chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which can be diagnosed prior to, simultaneous with, or following the myeloid neoplasm.3

The pathogenic mechanism underlying the increased risk of LPD in MPN patients is unknown, but it has been postulated that these disorders could share a common clonal origin.4 Genetic studies have demonstrated that certain genes, such as SF3B1, TET2, TP53, and BCOR, are mutated in both myelo- and lymphoproliferative diseases, as well as in healthy individuals with age-related clonal hematopoiesis (ARCH), a known precursor to overt malignancy.5-10 Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that CLL and hairy cell leukemia, mature B-cell neoplasms traditionally thought to arise in lineage-committed cells, may originate from multipotent hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), as disease-defining mutations have been identified in nonlymphoid progenitors and differentiated myeloid cells in some patients.11-13 It follows that ARCH, driven by pathogenic mutations in multipotent HSPCs, could serve as a substrate for the development of concurrent MPN/LPD.

To address this hypothesis, detailed genetic characterization of patients with concurrent MPN/LPD is required; prior reports have exclusively focused on JAK2 or CALR MPN driver mutations, with the majority showing no contribution to lymphoid disease.1,4,14-22 Here, we analyzed 3 patients diagnosed with both myelofibrosis (MF) and a mature B-cell LPD; their clinical features are summarized in Table 1 and supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood Web site). All biological samples used in this study were collected in accordance with the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network (REB#01-0573 and REB#02-0763). Patient-specific mutations were identified by sequencing DNA from whole peripheral blood (PB) using the Illumina TruSight Myeloid Panel, which covers regions of 54 genes relevant to ARCH and hematologic malignancy (Table 1; supplemental Tables 1 and 2; see supplemental Methods for details). Subsequently, to determine the contribution of these variants to normal and neoplastic hematopoiesis, digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) was performed on DNA from 5 subpopulations sorted from cryopreserved PB mononuclear cells (MNCs): monocytes, T cells, non–B-cell progenitors, normal B cells, and malignant B cells (supplemental Figure 2).

Clinical and molecular characteristics of study patients at the time of sample collection

| ID . | Age/sex . | Hematologic diagnoses . | Prior treatments . | FISH . | Karyotype . | PB counts . | Mutation data . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×109/L) . | Lymphocytes (×109/L) . | Blasts (×109/L) . | Gene . | Protein change . | VAF (%) . | ||||||

| A | 84/M | 1a. CLL* | 1. Chlorambucil | +12 | nd | 20.6 | 6.74 | 0.21 | NOTCH1 | p.Pro2514Argfs*4 | 5.2 |

| 1b. PMF* | 2. Ibrutinib | FBXW7 | p.Arg465Leu | 15.1 | |||||||

| BCOR | p.Gln1528* | 25.2 | |||||||||

| CALR | p.Leu367Thrfs*46 | 38.7 | |||||||||

| B | 76/F | 1. PET-MF with dysplastic acceleration | Hydroxyurea | Negative for t(11;14) | 46,XX,add(7)(q11.2),+8,-11, add(14)(q32),-17,+mar[10] | 16.0 | 10.14 | 0.16 | DNMT3A | p.Asn516Thrfs*135 | 20.0 |

| 2. CD5+ LPD, favor marginal zone derivation | JAK2 | p.Val617Phe | 18.4 | ||||||||

| TP53 | p.His193Pro | 21.1 | |||||||||

| C | 56/M | 1. PET-MF | Hydroxyurea | nd† | 46, XY [20] | 43.5 | 28.84 | 0 | MPL | p.Trp515Leu | 15.8 |

| 2. CLL | SRSF2 | p.Pro95His | 8.8 | ||||||||

| TET2 | p.Leu446Phefs*9 | 7.5 | |||||||||

| TET2 | p.His1219Arg | 10.3 | |||||||||

| ID . | Age/sex . | Hematologic diagnoses . | Prior treatments . | FISH . | Karyotype . | PB counts . | Mutation data . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×109/L) . | Lymphocytes (×109/L) . | Blasts (×109/L) . | Gene . | Protein change . | VAF (%) . | ||||||

| A | 84/M | 1a. CLL* | 1. Chlorambucil | +12 | nd | 20.6 | 6.74 | 0.21 | NOTCH1 | p.Pro2514Argfs*4 | 5.2 |

| 1b. PMF* | 2. Ibrutinib | FBXW7 | p.Arg465Leu | 15.1 | |||||||

| BCOR | p.Gln1528* | 25.2 | |||||||||

| CALR | p.Leu367Thrfs*46 | 38.7 | |||||||||

| B | 76/F | 1. PET-MF with dysplastic acceleration | Hydroxyurea | Negative for t(11;14) | 46,XX,add(7)(q11.2),+8,-11, add(14)(q32),-17,+mar[10] | 16.0 | 10.14 | 0.16 | DNMT3A | p.Asn516Thrfs*135 | 20.0 |

| 2. CD5+ LPD, favor marginal zone derivation | JAK2 | p.Val617Phe | 18.4 | ||||||||

| TP53 | p.His193Pro | 21.1 | |||||||||

| C | 56/M | 1. PET-MF | Hydroxyurea | nd† | 46, XY [20] | 43.5 | 28.84 | 0 | MPL | p.Trp515Leu | 15.8 |

| 2. CLL | SRSF2 | p.Pro95His | 8.8 | ||||||||

| TET2 | p.Leu446Phefs*9 | 7.5 | |||||||||

| TET2 | p.His1219Arg | 10.3 | |||||||||

F, female; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; M, male; nd, not done; PET-MF, post–essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis; PMF, primary myelofibrosis; VAF, variant allele frequency; WBC, white blood cell count.

Simultaneous diagnoses.

Single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis showed biallelic loss of a 1.17 Mb region at chromosome 13q14 and loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 1p.

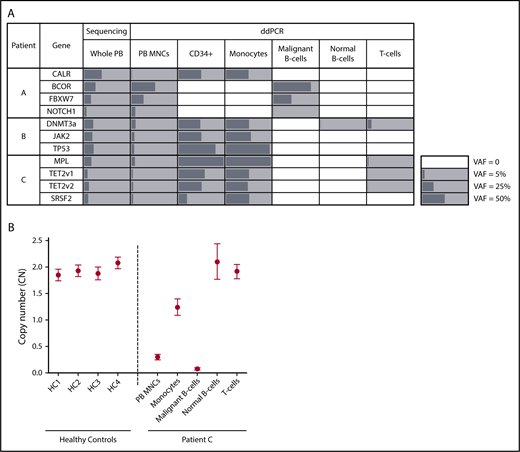

Targeted sequencing of PB from patient A, a male diagnosed with CLL and primary MF, identified mutations in CALR, BCOR, FBXW7, and NOTCH1 (Table 1). ddPCR detected all 4 mutations in unsorted MNCs (Figure 1A); however, compared with VAFs generated by sequencing whole PB, these values were lower for MPN-associated genes and higher for CLL-associated genes, a consequence of Ficoll-Hypaque separation, which depletes neutrophils during the isolation of MNCs. Analysis of sorted PB subfractions demonstrated that the BCOR, FBXW7, and NOTCH1 mutations were detected only in CLL cells; the CALR deletion was found only in progenitors and monocytes; and the T- and normal B-cell fractions were devoid of all variants (Figure 1A). Thus, mutation distribution enabled clear delineation of MPN, CLL, and normal hematopoietic cells within this patient’s blood. Notably, the MPN clone included not only mature myeloid cells, but also dominated PB progenitors, a consequence of the circulating clonal CD34+ cells characteristic of MF.23

Mutational and copy number (CN) analysis of sorted PB subpopulations in patients with concurrent MPN/LPD. (A) Allele frequencies (%) of patient-specific variants in whole PB, unsorted PB MNCs, and PB subpopulations as determined by targeted sequencing (whole PB) or ddPCR (unsorted MNCs and sorted fractions). Mutation-positive fractions are shaded in gray, with the length of the bars proportional to the VAF. White squares indicate populations where variants were not detected. TET2 v1 (TET2 variant 1) refers to the TET2 L446fs variant; TET2 v2 (TET2 variant 2) refers to the TET2 H1219R variant. In patient C, the MPL W515L VAF exceeded 99% in the CD34+/monocyte fractions, consistent with the known loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 1p in this patient. (B) CN at the chromosome 13q14 locus as determined by ddPCR in unsorted PB MNCs and PB subpopulations from patient C as well as PB MNCs from 4 healthy controls (HC). CN measurements are depicted by a circle, with error bars indicating the 95% confidence interval.

Mutational and copy number (CN) analysis of sorted PB subpopulations in patients with concurrent MPN/LPD. (A) Allele frequencies (%) of patient-specific variants in whole PB, unsorted PB MNCs, and PB subpopulations as determined by targeted sequencing (whole PB) or ddPCR (unsorted MNCs and sorted fractions). Mutation-positive fractions are shaded in gray, with the length of the bars proportional to the VAF. White squares indicate populations where variants were not detected. TET2 v1 (TET2 variant 1) refers to the TET2 L446fs variant; TET2 v2 (TET2 variant 2) refers to the TET2 H1219R variant. In patient C, the MPL W515L VAF exceeded 99% in the CD34+/monocyte fractions, consistent with the known loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 1p in this patient. (B) CN at the chromosome 13q14 locus as determined by ddPCR in unsorted PB MNCs and PB subpopulations from patient C as well as PB MNCs from 4 healthy controls (HC). CN measurements are depicted by a circle, with error bars indicating the 95% confidence interval.

Patient B, a female with a low-grade CD5+CD20+ LPD and PET-MF, carried a JAK2 V617F mutation as well as DNMT3a and TP53 variants (Table 1). All 3 mutations were detected in the monocytes and progenitors but were absent from LPD cells (Figure 1A). Notably, in the normal B- and T-cell fractions, the DNMT3a mutation was detected in the absence of JAK2 and TP53 alterations, indicating the presence of DNMT3a-driven ARCH ancestral to the development of this patient’s MPN. However, given that this variant was absent from CLL cells, this ARCH clone did not serve as the origin of her LPD.

A similar mutational distribution was noted in patient C, a male with CLL and PET-MF. Sequencing identified pathogenic variants in MPL, SRSF2, and TET2, all of which were present in monocytes and progenitors, but not CLL cells (Figure 1A). In T cells, the MPL and TET2 mutations were detected at low frequency (<2%), without the SRSF2 variant. Although the presence of 3 mutations in this fraction could suggest contamination by cells from the MPN clone, this is unlikely given the purity of the sorted fraction (supplemental Figure 3), and the notable absence of one of the MPN-associated variants. Instead, this pattern is suggestive of underlying ARCH, skewed toward T- vs B-lymphopoiesis, which, like patient B, was ancestral only to the myeloid neoplasm.

These results demonstrate that, at this level of genetic interrogation, mutational patterns segregate the MPN and LPD disease clones in patients with concurrent diagnoses. Importantly, ARCH was detected in 2 of 3 patients in this study, and in both instances, exclusively involved mutations that contributed to myeloid disease. Thus, ARCH with known driver did not serve as the shared origin of concurrent MPN/LPD in these individuals. Although our sequencing panel captures the canonical ARCH drivers, rare somatic driver, nondriver, or CN alterations shared between the 2 disease processes cannot be ruled out.

To address this possibility, we took 2 experimental approaches. First, X-inactivation patterns were assessed in the monocyte and malignant B cells of patient B, our sole female subject. The active X-chromosome, as determined by the human androgen receptor (HUMARA) assay, differed between MPN and LPD cells (supplemental Figure 4), establishing the distinct clonal origins of the 2 diseases. Second, given the recent finding that loss of chromosome 13q14 in the PB of healthy individuals is associated with an increased risk of CLL,24 we interrogated 13q14 CN status in patient C, who was known to carry this lesion. As expected, CLL cells showed evidence of biallelic 13q14 deletions, whereas the CN of normal B- and T-cell populations at this locus was comparable to diploid controls (Figure 1B). Surprisingly, monocytes showed evidence of monoallelic deletion of 13q14, suggesting that loss of 1 copy of this locus was a shared ancestral event for this patient’s MPN and LPD. Consistent with a role for this lesion in MPN pathogenesis, 13q loss is a frequently observed karyotypic abnormality in MF.25

Thus, our study adds clarity to the apparent contradictory results from previous studies of patients with concurrent MPN/LPD: distinct clonal origins were suggested in a study of X-inactivation pattern in 3 females with MPN and CLL,18 whereas other reports have found that JAK2 mutations can be detected in LPD cells in a subset of patients.1,19-21 Our findings suggest that the pathogenic processes underlying concurrent MPN/LPD can vary between patients. In some cases (as observed in patient B), the 2 disease clones originate independently and environmental factors or a germ-line predisposition state likely drive their parallel development. Alternatively, as seen in patient C, the 2 disease processes can have a common clonal origin, with an early shared genetic lesion prior to divergence. Notably, mutations in canonical ARCH drivers were not found to be the unifying origin of MPN and LPD disease clones in this study. Instead, we observed that a CN alteration could serve as an early shared genetic lesion. This finding highlights the key role played by noncanonical ARCH in the pathogenesis of hematologic malignancies and underscores a requirement for genome-wide mutational and CN analyses in future studies of concurrent MPN/LPD.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank N. Simard and S. Laronde for flow sorting, as well as Brian Parkin (University of Michigan) for providing the probe/primer sequences used to interrogate SRSF2.

This work was supported by grants from the Elizabeth and Tony Comper Foundation and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.K. designed the study and performed research, collected clinical information, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; J.J.F.M. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.M.D. performed research and analyzed data; A.A. collected patient samples; A.T. provided clinical flow cytometric data; M.D.M. provided patient samples; M.A.S., T.S., and S.K.-R. performed and analyzed sequencing data; J.E.D. and V.G. designed research and wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Vikas Gupta, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, 6th Floor-326, 700 University Ave, Toronto, ON M5G 1Z5, Canada; e-mail: vikas.gupta@uhn.ca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal