Key Points

Inhibiting CDK6 kinase function enhances long-term HSC functionality.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 and MAZ influence HSC maintenance.

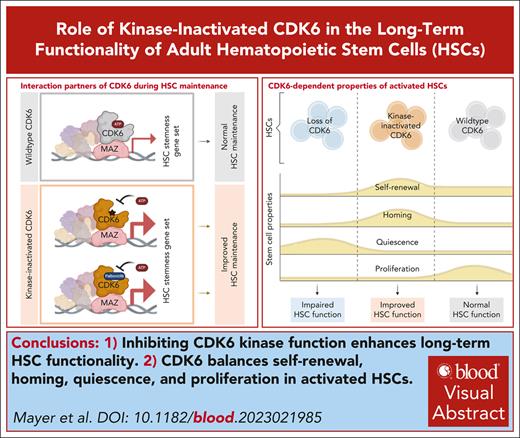

Visual Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are characterized by the ability to self-renew and to replenish the hematopoietic system. The cell-cycle kinase cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) regulates transcription, whereby it has both kinase-dependent and kinase-independent functions. Herein, we describe the complex role of CDK6, balancing quiescence, proliferation, self-renewal, and differentiation in activated HSCs. Mouse HSCs expressing kinase-inactivated CDK6 show enhanced long-term repopulation and homing, whereas HSCs lacking CDK6 have impaired functionality. The transcriptomes of basal and serially transplanted HSCs expressing kinase-inactivated CDK6 exhibit an expression pattern dominated by HSC quiescence and self-renewal, supporting a concept, in which myc-associated zinc finger protein (MAZ) and nuclear transcription factor Y subunit alpha (NFY-A) are critical CDK6 interactors. Pharmacologic kinase inhibition with a clinically used CDK4/6 inhibitor in murine and human HSCs validated our findings and resulted in increased repopulation capability and enhanced stemness. Our findings highlight a kinase-independent role of CDK6 in long-term HSC functionality. CDK6 kinase inhibition represents a possible strategy to improve HSC fitness.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are rare components of the adult bone marrow (BM), in which they preserve the hematopoietic pool by self-renewal and differentiation.1-3 Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an essential medical procedure for various hematological diseases.4-6 Although HSCT is a life-saving process, it has several limitations due to graft-versus-host disease or relapse.4,5 The objective is to use the most functional and fittest HSCs for a successful HSCT.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) controls the exit from the G1 phase of the cell cycle in all cells. The cell cycle is triggered by binding of CDK6 to D-type cyclins, which activates the kinase function of CDK6 and leads to phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. Subsequent E2F-mediated transcription causes the cells to exit G1 and enter the S phase.7 In addition to phosphorylating retinoblastoma protein, CDK6 regulates the transcription of a range of genes in healthy and malignant cells. It does not itself bind to DNA but interacts with a plethora of transcription factors, either in a kinase-dependent or in a kinase-independent manner.8-13 Using transgenic CDK6 animal models has been instrumental in our understanding of the complex interplay of the kinase-dependent and -independent functions of CDK6 in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).14,15 However, we do not understand how CDK6 controls the fate of these cells.

We now report that inactivation of the kinase function of CDK6 leads to an enriched pool of quiescent HSCs with a long-term capacity to repopulate the hematopoietic system. We also show that HSCs containing a kinase-inactivated version of CDK6 retain certain features of stem cells that are lost when the HSCs lack CDK6. Our transcriptomics data provide a model to explain how CDK6 stimulates or represses various transcriptional networks to control the fate of HSCs.

Methods

Serial BM transplantation assays

A total of 5 × 106Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, or Cdk6KM/KM donor BM cells were transplanted intravenous (IV) into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. The long-term repopulation capacities were evaluated after 12 weeks following transplantation by flow cytometry. For up to 4 rounds, 5 × 106 CD45.2+ donor BM cells were re-injected in lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice.

Single and repetitive pI:pC injections

Mice were injected once intraperitoneally with 10 mg/kg polyinosinic polycytidylic acid (pI:pC). Control mice were injected with the same volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were dissected 18 hours after treatment, and the HSC compartment was analyzed.

For repetitive analysis, mice were serially injected intraperitoneally on every second day (3 times total) with 10 mg/kg pI:pC or PBS. Mice were dissected 2 days after the third injection.

All procedures and breeding were approved by the Ethics and Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna in accordance with the University’s guidelines for Good Scientific Practice, and authorized by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMMWF-68.205/0093-WF/V/3b/2015, 2022-0.404.452, BMMWF-68.205/0112-WF/V/3b/2016, BMBWF-68.205/0103-WF/V/3b/2015 [TP], and 2023-0.108.862) in accordance with current legislation. The experimental protocols involving human cord blood samples were approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK1553/2014).

Other methods are described in detail in supplemental Method, available on the Blood website.

Results

CDK6 shapes the HSC transcriptomic landscape in a kinase-dependent and -independent manner

To understand the contribution of kinase-dependent and -independent functions of CDK6 in HSCs, we used a kinase-inactivated CDK6 K43M knockin mouse model (Cdk6KM/KM),14 which was compared with CDK6 wild type (Cdk6+/+) and CDK6 knockout mice (Cdk6–/–).15 HSPC fractions of Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM mice showed comparable CDK6 protein levels (supplemental Figure 1A-C). Although BM cellularity was reduced in Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– mice, LSK (Lin–Sca-1+c-kit+) cell numbers remained unaffected (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1D). HSC cell numbers were increased, and multipotent progenitor 3/4 (MPP3/4) cell numbers were reduced in the Cdk6KM/KM mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice, whereas Cdk6–/– mice showed reduced MPP2 cell numbers compared with Cdk6+/+ mice (Figure 1A). Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– mice showed a significantly increased percentage of the HSC subfraction, whereas the percentage of LSK and MPP1-4 cells remained unaltered irrespective of the genotype (supplemental Figure 1E-F).

CDK6 shapes the HSC transcriptomic landscape in a kinase-inactivated, kinase-dependent, and -independent manner. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of isolated BM from Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM mice. Cell numbers of HSCs (LSK [Lin–Sca-1+c-kit+] CD34–CD48–CD150+CD135–), MPP1 (LSK CD34+CD48–CD150+CD135–), MPP2 (LSK CD48+CD150+), and MPP 3/4 (LSK CD48+CD150–) (n = 10; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (B) Experimental scheme of 10x Genomics scRNA-seq including flow cytometry sorting of LSK cells of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM (top). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of 11 LSK cell clusters (bottom). Colors indicate different clusters. (C) UMAP of 9 HSPC subclusters with color code. (D) Bar chart of HSPC subcluster size differences of either Cdk6–/– or Cdk6KM/KM compared with the Cdk6+/+ control (Log2FC of percent cluster sizes relative to Cdk6+/+). (E) UMAP of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSPC cluster. The arrow indicates HSC subcluster. (F) Classification of CDK6 states: kinase-inactivated, kinase-dependent, and loss of CDK6 (top). Venn diagrams showing number of genes of the HSC subcluster uniquely (bottom) or commonly upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) in Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ (|Log2FC| ≥ 0.3). (G) UMAP showing Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSPCs overlaid with the HSC–associated proliferation gene signature (Psig).16 The 15% of cells with the lowest Psig score (compare methods) are indicated in blue. Violin plots depict Psig and HSC–associated quiescent signature (Qsig) of all 3 genotypes. Cycle, cell cycle; Ery, erythroid; Rep, replication. ∗P < .05.

CDK6 shapes the HSC transcriptomic landscape in a kinase-inactivated, kinase-dependent, and -independent manner. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of isolated BM from Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM mice. Cell numbers of HSCs (LSK [Lin–Sca-1+c-kit+] CD34–CD48–CD150+CD135–), MPP1 (LSK CD34+CD48–CD150+CD135–), MPP2 (LSK CD48+CD150+), and MPP 3/4 (LSK CD48+CD150–) (n = 10; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (B) Experimental scheme of 10x Genomics scRNA-seq including flow cytometry sorting of LSK cells of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM (top). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of 11 LSK cell clusters (bottom). Colors indicate different clusters. (C) UMAP of 9 HSPC subclusters with color code. (D) Bar chart of HSPC subcluster size differences of either Cdk6–/– or Cdk6KM/KM compared with the Cdk6+/+ control (Log2FC of percent cluster sizes relative to Cdk6+/+). (E) UMAP of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSPC cluster. The arrow indicates HSC subcluster. (F) Classification of CDK6 states: kinase-inactivated, kinase-dependent, and loss of CDK6 (top). Venn diagrams showing number of genes of the HSC subcluster uniquely (bottom) or commonly upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) in Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ (|Log2FC| ≥ 0.3). (G) UMAP showing Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSPCs overlaid with the HSC–associated proliferation gene signature (Psig).16 The 15% of cells with the lowest Psig score (compare methods) are indicated in blue. Violin plots depict Psig and HSC–associated quiescent signature (Qsig) of all 3 genotypes. Cycle, cell cycle; Ery, erythroid; Rep, replication. ∗P < .05.

To determine underlying transcriptional changes in the HSC compartment, we performed high-resolution 10x Genomics single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of steady-state BM LSK cells. Data integration identified 11 individual cell clusters, which we annotated according to published marker gene expression (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1G).17,18 Differences in cluster sizes were notable between Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ cells (supplemental Figure 1H). In line with the known cell cycle function of CDK6,7,14,15 the “cell cycle clusters” in Cdk6–/– and Cdk6KM/KM samples were smaller than the Cdk6+/+ cluster. Flow cytometry analysis of ex vivo and cultivated Cdk6–/– and Cdk6KM/KM LSK or HSC/MPP1 cells verified reduced proliferation (supplemental Figure 1I-J).

The HSPC cluster of the scRNA-seq experiment encompassed ∼20% of all LSK cells (Figure 1B). To better identify transcriptional patterns in more defined HSPCs, we reintegrated the HSPC cluster and annotated dormant HSCs and differentiation-prone cell states based on published marker genes (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1K).17,18 We found 9 HSPC subclusters that exhibited transcriptional alterations, particularly in the Cdk6KM/KM mutant setting when compared with Cdk6+/+ or Cdk6–/– cells. All Cdk6KM/KM clusters showed a more pronounced effect in size compared with Cdk6–/– clusters, except the cell cycle cluster. We identified opposing effects of Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– cells within the myeloid (Myel), lymphoid (Lym), and interferon (IFN) HSPC subclusters. Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– samples showed increased dormant HSCs to a similar extent as shown in Figure1A (Figure 1D). Strikingly, Cdk6KM/KM HSCs displayed a unique transcriptional pattern leading to an alternative cluster formation (Figure 1E). Differential gene expression analysis of the dormant HSC subcluster unmasked common and unique upregulated and downregulated genes in Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ cells (Figure 1F). Cdk6KM/KM HSCs showed on average a reduced expression of a proliferation gene signature16 compared with Cdk6–/– and Cdk6+/+ cells (Figure 1G). Cdk6–/– cells showed a stronger expression of the quiescence-associated signature16 compared with Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6+/+ cells. This result aligns with our previously published data, highlighting that the absence of CDK6 impairs HSC exit from their quiescent state, along with decreased response to HSC-specific stress conditions.13 These data led us to speculate that Cdk6KM/KM HSCs respond differently to HSC-specific stress challenge compared with Cdk6–/– HSCs. Kinase-inactivated CDK6 fails to phosphorylate, despite the protein being present, which may block other kinases that compensate in a CDK6-deficient setting.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 maintains HSPC potential upon long-term challenge

The transcriptional changes found in Cdk6KM/KM HSCs point toward alterations in IFN response and activation. We thus injected mice with a single dose of pI:pC to analyze the activation response in a short-term setting (supplemental Figure 2A). To control for the induction of Sca-1 expression by the IFN-STAT1 axis, we decided on an alternative flow cytometry gating strategy including the CD86 marker.19 Lineage– c-kit+ CD86+ cell numbers were similar among the 3 genotypes upon pI:pC treatment (supplemental Figure 2B). As under steady-state conditions, HSC/MPP1-2 cell numbers were significantly higher in Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ mice. This was not detected for the Cdk6–/– mice (supplemental Figure 2C). Cdk6–/– HSC/MPP1 cells showed reduced G1 cell cycle entry upon single pI:pC stimulation, in line with published data13 (supplemental Figure 2D).

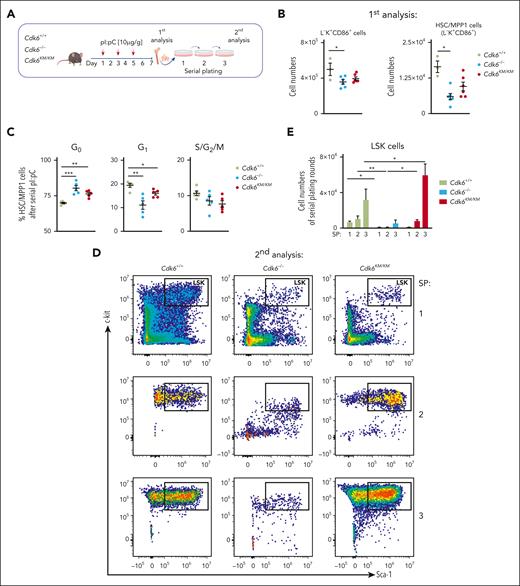

To test how Cdk6KM/KM cells respond to multiple inflammation-associated challenges, we performed serial pI:pC injections followed by serial plating assays to study long-term self-renewal (Figure 2A).

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 maintains HSPC potential upon long-term challenge. (A) Experimental workflow of repetitive in vivo pI:pC injections followed by an in vitro serial plating assay of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM cells. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of L–K+CD86+ and HSC-MPP1 (from L–K+CD86+) cells upon serial pI:pC injection (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM). (C) Cell cycle distribution of HSC/MPP1 cells upon serial pI:pC treatment (n=5, mean ± SEM). (D) Representative flow cytometry plots showing serially plated LSK cells upon repetitive pI:pC treatment. (E) Relative quantification of LSK cells during serial plating after repetitive in vivo pI:pC treatment (n = 3-6, mean ± SEM). SP, serial plating. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 maintains HSPC potential upon long-term challenge. (A) Experimental workflow of repetitive in vivo pI:pC injections followed by an in vitro serial plating assay of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM cells. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of L–K+CD86+ and HSC-MPP1 (from L–K+CD86+) cells upon serial pI:pC injection (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM). (C) Cell cycle distribution of HSC/MPP1 cells upon serial pI:pC treatment (n=5, mean ± SEM). (D) Representative flow cytometry plots showing serially plated LSK cells upon repetitive pI:pC treatment. (E) Relative quantification of LSK cells during serial plating after repetitive in vivo pI:pC treatment (n = 3-6, mean ± SEM). SP, serial plating. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Serial pI:pC injections resulted in decreased BM cellularity in Cdk6–/– and Cdk6KM/KM mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice, along with decreased Cdk6–/– L–K+CD86+ and HSC/MPP1 cell numbers (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2E). Cdk6KM/KM cells displayed intermediate numbers. MPP2-4 cells remained unchanged irrespective of the genotype (supplemental Figure 2F). A higher percentage of Cdk6–/– and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells remained in the G0 and G1 cell cycle phases (Figure 2C). Our experimental setting was completed by serially plating BM cells into methylcellulose (Figure 2A). Serial BM cell plating revealed significantly elevated Cdk6KM/KM LSK cell numbers. In contrast, Cdk6–/– cells showed reduced LSK cell numbers and even more drastically reduced total cell numbers compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM cells (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Figure 2G). Cdk6KM/KM colonies displayed an overall reduction in differentiated cells compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– controls upon serial plating, yet Cdk6KM/KM cells were still able to produce Myel and Lym colonies (supplemental Figure 2H). The short-term and long-term pI:pC data suggest that kinase-inactivated CDK6 mimics full loss of CDK6 in regard to cell cycle, which can be observed most prominently in a short-term activation setting. However, in a repetitive activation setting, where long-term stem cell properties come into account, kinase-inactivated CDK6 maintained LSK numbers, whereas loss of CDK6 led to reduced LSK cell numbers. The advantage of Cdk6KM/KM HSCs comes with only mild expenses regarding the differentiation potential.

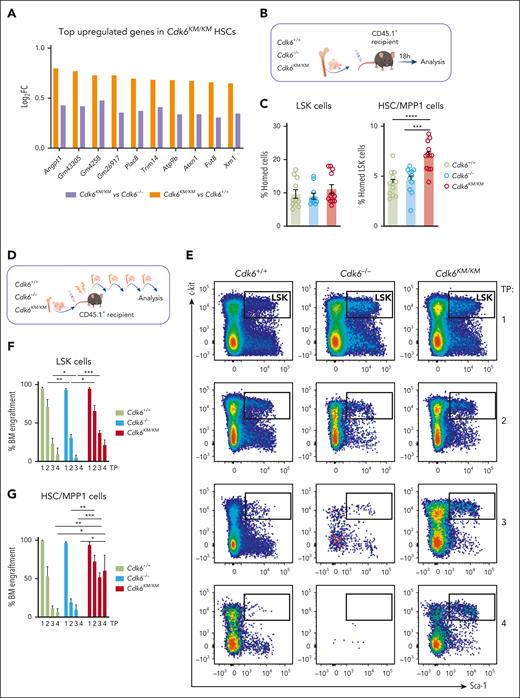

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 enhances HSC homing and self-renewal

Angiopoietin 1 (Angpt1) was 1 of the most upregulated genes in Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– cells from the dormant HSC subcluster (Figure 3A). As Angpt1/Tie2 is a critical signaling component for HSC quiescence and homing,20,21 we tested whether kinase-independent functions of CDK6 affect homing and migration of HSCs (supplemental Figure 3A). Sorted LSK cells were plated in a transwell system including stromal cell-derived factor 1α as an attractant. No changes in migration of the total LSK compartment were observed. When analyzing HSC/MPP1 cells, Cdk6KM/KM cells migrated significantly more than Cdk6–/– HSC/MPP1 cells in vitro. Therefore, we performed an in vivo homing assay. We injected CD45.2+ LSK cells of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM mice IV into CD45.1+ recipient mice (Figure 3B). Injected CD45.2+ LSK and MPP2-4 progenitor cells were similarly present in the BM irrespective of the genotype 18 hours thereafter (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 3B). In contrast, significantly more Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells homed to the BM compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– HSC/MPP1 cells.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 enhances HSC homing and self-renewal. (A) Top upregulated genes in dormant Cdk6KM/KM HSCs compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– cells from scRNA-seq. (B) Schematic representation of BM homing assay in vivo. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of homed CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM LSK and HSC/MPP1 of LSK cells 18 hours after injection into CD45.1+ recipients (n ≥ 11 recipients and donors, mean ± SEM). (D) Serial BM transplantation workflow of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM cells. (E) Representative flow cytometry plots of gated LSK cells over 4 rounds of transplantation (TP). (F-G) Percentage of engrafted CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM LSK and HSC/MPP1 cells over 4 rounds of transplantation. (H) Lineage distribution of engrafted CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM cells (n = 3-6/genotype, mean ± SEM). (I) Experimental-design competitive BM transplantation assay, depicting a 1:1 ratio transplantation of CD45.1+Cdk6+/+ together with either CD45.2+Cdk6+/+ or Cdk6KM/KM BM into lethally irradiated recipient mice. (J) End point analysis of competitive transplantation showing CD45.2+Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells (n = 7 per group, mean ± SEM). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 enhances HSC homing and self-renewal. (A) Top upregulated genes in dormant Cdk6KM/KM HSCs compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– cells from scRNA-seq. (B) Schematic representation of BM homing assay in vivo. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of homed CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM LSK and HSC/MPP1 of LSK cells 18 hours after injection into CD45.1+ recipients (n ≥ 11 recipients and donors, mean ± SEM). (D) Serial BM transplantation workflow of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM cells. (E) Representative flow cytometry plots of gated LSK cells over 4 rounds of transplantation (TP). (F-G) Percentage of engrafted CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM LSK and HSC/MPP1 cells over 4 rounds of transplantation. (H) Lineage distribution of engrafted CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM cells (n = 3-6/genotype, mean ± SEM). (I) Experimental-design competitive BM transplantation assay, depicting a 1:1 ratio transplantation of CD45.1+Cdk6+/+ together with either CD45.2+Cdk6+/+ or Cdk6KM/KM BM into lethally irradiated recipient mice. (J) End point analysis of competitive transplantation showing CD45.2+Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells (n = 7 per group, mean ± SEM). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Self-renewal and homing are processes involved in HSC engraftment. To assess the repopulation capacity of Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells, we serially transplanted BM cells from CD45.2+Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM mice into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice (Figure 3D). From the second round of transplantation onward, we identified significantly higher numbers of donor-derived Cdk6KM/KM LSK cells compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– LSK cells (Figure 3E-F). This effect was even more pronounced for the HSC/MPP1 cell compartment (Figure 3G). In contrast to Cdk6KM/KM cells, Cdk6–/– LSK and HSC/MPP1 cells significantly declined over serial rounds of transplantation. Cdk6KM/KM MPP2-4 progenitor cells displayed higher percentages of BM engraftment compared with Cdk6–/– MPP2-4 cells within all transplantation rounds (supplemental Figure 3C). No significant differences in the MPP2-4 cells were observed between Cdk6KM/KM and CDK6 wild-type cells.

Comparable percentages of Myel and Lym cells were found upon repopulation of Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM cells in the long-term transplantation setting (Figure 3H). Of note, Cdk6–/– cells showed a shift from the Myel to the Lym lineage, with the strongest effect observed in the second serial transplantation round. These data are consistent with the enhanced Lym HSPC subcluster identified by the scRNA-seq data (Figure 1D). No significant alterations were detected in the composition of the peripheral blood (supplemental Figure 3D). To further investigate the functionality of CDK6 kinase-inactivated HSC/MPP1 cells, we performed competitive transplantation assays with Cdk6KM/KM or Cdk6+/+ BM cells (Figure 3I). Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells showed a competitive advantage compared with control counterparts (Figure 3J). No major differences in the MPP2-4 fractions and LSK cells between Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM were observed (supplemental Figure 3F-G). These results highlight a specific role for kinase-inactivated CDK6 in the repopulation ability of HSCs, which is not mimicked by full loss of CDK6. Cdk6KM/KM HSCs balance proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal through a unique mechanism of transcriptional regulation.

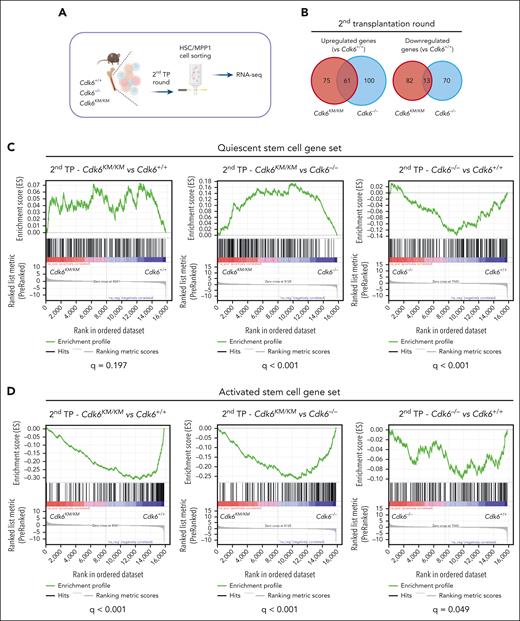

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 balances quiescent and activated transcriptional programs of long-term HSCs

To gain deeper insights into how kinase-inactivated CDK6 protects HSCs during long-term challenge, we performed low-input RNA-seq of flow cytometry–sorted serially transplanted (second round) HSC/MPP1 cells (Figure 4A). Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– cells showed unique and common transcriptional changes (Figure 4B). From the scRNA-seq analysis, we identified a gene set associated with kinase-inactivated CDK6, kinase-dependent activity, and CDK6 loss. We first defined gene sets associated with HSC quiescence or HSC activation (supplemental Figure 4A).22Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells displayed a positive enrichment of the quiescent stem cell gene set compared with Cdk6–/– HSC/MPP1 cells (Figure 4C). This finding reflected the reduced engraftment potential of the Cdk6–/– HSC/MPP1 cells over Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells (Figure 3G). A significant negative enrichment of the activation stem cell gene set was identified for Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– HSC/MPP1 cells compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells, which aligns with the proliferation-associated gene signature from the dormant HSC cluster (Figure 1G and 4D). These results highlight the importance of kinase-independent effects of CDK6 in maintaining quiescent gene expression patterns, which becomes critical under HSC long-term behavior. Under homeostasis, we previously observed the regulation of the Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– quiescent genes. In these conditions, we identified a different transcriptional pattern of the dormant Cdk6KM/KM HSC subcluster (Figure 1E-G).

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 balances quiescent and activated transcriptional programs of HSCs. (A) Experimental workflow of low-input RNA-seq of engrafted CD45.2+ HSC/MPP1 cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (B) Venn diagrams showing genes uniquely or commonly upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) in Cdk6–/– and Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation (n=3; |Log2FC| ≥ 0.3; adjusted P value < .2). (C-D) Gene set enrichment analysis to test for the enrichment of quiescent or activated stem cell gene sets in differentially expressed genes coming from 3 analyses: HSC/MPP1 cells of Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ cells, Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6–/–, or Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (E-F) Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis of genes within the activated stem cell gene set that are either upregulated in (E) Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells or (F) Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells upon 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (G) Subcellular fractionation of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cells, followed by western blot analysis of CDK6. Lamin B1/regulator of chromosome condensation 1 (RCC1) served as a nuclear marker, whereas heat shock protein 90 (HSP-90) served as a cytoplasmic marker. (H) Anti-NFY-A co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) from Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cell extracts followed by NFY-A and CDK6 immunoblotting. IN indicates the input lysate and SN indicates the supernatant after IP. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as loading control.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 balances quiescent and activated transcriptional programs of HSCs. (A) Experimental workflow of low-input RNA-seq of engrafted CD45.2+ HSC/MPP1 cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (B) Venn diagrams showing genes uniquely or commonly upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) in Cdk6–/– and Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation (n=3; |Log2FC| ≥ 0.3; adjusted P value < .2). (C-D) Gene set enrichment analysis to test for the enrichment of quiescent or activated stem cell gene sets in differentially expressed genes coming from 3 analyses: HSC/MPP1 cells of Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ cells, Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6–/–, or Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (E-F) Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis of genes within the activated stem cell gene set that are either upregulated in (E) Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells or (F) Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ HSC/MPP1 cells upon 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (G) Subcellular fractionation of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cells, followed by western blot analysis of CDK6. Lamin B1/regulator of chromosome condensation 1 (RCC1) served as a nuclear marker, whereas heat shock protein 90 (HSP-90) served as a cytoplasmic marker. (H) Anti-NFY-A co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) from Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cell extracts followed by NFY-A and CDK6 immunoblotting. IN indicates the input lysate and SN indicates the supernatant after IP. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as loading control.

The CDK6 protein lacks a DNA-binding domain and acts as a transcriptional cofactor.7-9,11,14 To understand how CDK6 regulates HSC self-renewal and maintenance, we performed a transcription factor motif analysis in promoter regions of the differentially expressed activation signature genes between kinase-inactivated CDK6 and wild-type CDK6.

NFY and E2F motifs emerged as the most significant findings (Figure 4E). When performing a motif enrichment analysis for the comparison of Cdk6–/– with Cdk6+/+cells, we identified a pattern similar to that of the Cdk6KM/KM mutant compared with Cdk6+/+ cells (Figure 4F). These results validated the canonical cell cycle function of CDK6. Our results also confirmed published data on NFY-A, showing that it is a critical factor in proliferating HSCs.

We recently described that CDK6 phosphorylates NFY-A at serine position S325 in breakpoint cluster region and Abelson chimeric gene (BCR/ABL) transformed cells. Thereby, NFY-A is activated for its transcriptional function.10

To validate a CDK6–NFY-A interaction in hematopoietic progenitor cells, we took advantage of our recently established HPCLSK system and generated stem/progenitor cell lines from Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM mice.23 Subcellular fractionation analysis revealed that kinase-inactivated and wild-type CDK6 protein was comparable in the chromatin and cytoplasmic fractions (Figure 4G) in HPCLSK cells, predicting that kinase-inactivated CDK6 interacts with the chromatin in a similar manner as wild-type CDK6. Coimmunoprecipitation confirmed the protein-protein interaction of CDK6 and NFY-A in Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cells (Figure 4H). To better understand the significance of this interaction, we performed NFY-A short hairpin RNA knockdown experiments with Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cells. Upon NFY-A knockdown, Cdk6KM/KM HPCLSK cells responded with increased cell death compared with Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6–/– cells (supplemental Figure 4B-C). These data are consistent with previous reports that NFY-A loss induces apoptosis and CDK6 kinase activity is needed to antagonize p53-responses.10,24,25

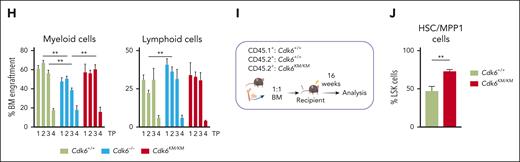

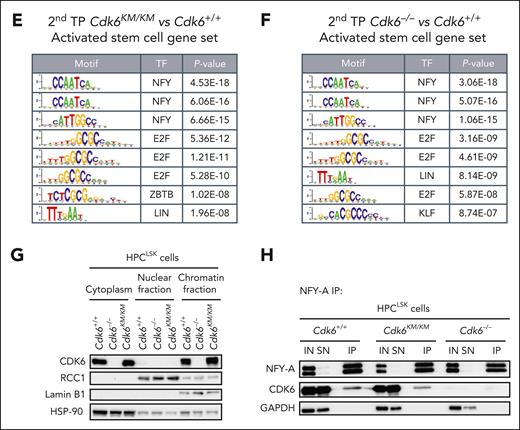

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 and MAZ influence HSC maintenance

To identify kinase-inactivated CDK6 interactors maintaining quiescence, we combined motif enrichment analysis with a CDK6 immunoprecipitation–mass spectrometry experiment. We performed motif enrichment analysis of Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– deregulated genes compared with Cdk6+/+ within the quiescent stem cell gene set, and defined Cdk6KM/KM-specific motifs (Figure 5A-B; supplemental Figure 5A). We performed a nuclear CDK6 immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry analysis with the hematopoietic progenitor cell line HPC-726 (Figure 5C). An overlap of these data with the Cdk6KM/KM-specific motifs highlighted ZNF148, RUNX1, and MAZ as the strongest interactors. The MAZ-CDK6 interaction was validated by proximity ligation assays in Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells (Figure 5D).

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 and MAZ influence HSC maintenance. (A-B) Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis of genes within the quiescent stem cell gene set that are either upregulated in (A) Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ cells or (B) Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (C) CDK6 interactome analysis generated by nuclear CDK6-IP mass spectrometry analysis of HPC-7 cell lines expressing either wild-type CDK6 or CDK6KM. Dot plot illustrating all protein interactions with CDK6 or CDK6KM vs CDK6–/– (Log2FC). Established CDK6 interactors are highlighted in blue. Transcription factors interacting with CDK6KM and analyzed from the CDK6KM specific motif analysis from supplemental Figure 5A are highlighted in red. (D) Flow cytometry proximity ligation assay of CDK6 and MAZ antibodies showing endogenous protein interaction in ex vivo Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells. Representative flow cytometry histograms are depicted on the right. Cdk6–/– cells, MAZ, and CDK6 antibody only samples served as controls. (E) Overlap of CDK6 ChIP-seq data from BCR/ABLp185+ cells with published MAZ ChIP-seq data from CH12.LX mouse lymphoma cell line. (F) Annotation of the genomic regions identified in the CDK6/MAZ ChIP-seq overlap. (G) CDK6/MAZ ChIP-seq overlay (+2 kb to –500 bp to transcription start site [TSS]) with upregulated genes of Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ dormant HSC subcluster genes (scRNA-seq FC ≥ 0.3). (H) Stem cell genes of Cdk6KM/KM or Cdk6–/– cells compared with Cdk6+/+ cells with a CDK6-MAZ ChIP peak. (I) Experimental design of siRNA MAZ knockdown assay in sorted Cdk6+/+LSK cells ± palbociclib treatment and in Cdk6KM/KM LSK cells. (J-K) Flow cytometry analysis of (J) HSC/MPP1 scramble cells and (K) HSC/MPP1 cell subset of LSK cells upon MAZ knockdown ± palbociclib treatment depicted as Log2FC relative to corresponding scramble controls (n = 4 per genotype, mean ± SEM). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P< .01.

Kinase-inactivated CDK6 and MAZ influence HSC maintenance. (A-B) Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis of genes within the quiescent stem cell gene set that are either upregulated in (A) Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ cells or (B) Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (C) CDK6 interactome analysis generated by nuclear CDK6-IP mass spectrometry analysis of HPC-7 cell lines expressing either wild-type CDK6 or CDK6KM. Dot plot illustrating all protein interactions with CDK6 or CDK6KM vs CDK6–/– (Log2FC). Established CDK6 interactors are highlighted in blue. Transcription factors interacting with CDK6KM and analyzed from the CDK6KM specific motif analysis from supplemental Figure 5A are highlighted in red. (D) Flow cytometry proximity ligation assay of CDK6 and MAZ antibodies showing endogenous protein interaction in ex vivo Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells. Representative flow cytometry histograms are depicted on the right. Cdk6–/– cells, MAZ, and CDK6 antibody only samples served as controls. (E) Overlap of CDK6 ChIP-seq data from BCR/ABLp185+ cells with published MAZ ChIP-seq data from CH12.LX mouse lymphoma cell line. (F) Annotation of the genomic regions identified in the CDK6/MAZ ChIP-seq overlap. (G) CDK6/MAZ ChIP-seq overlay (+2 kb to –500 bp to transcription start site [TSS]) with upregulated genes of Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ dormant HSC subcluster genes (scRNA-seq FC ≥ 0.3). (H) Stem cell genes of Cdk6KM/KM or Cdk6–/– cells compared with Cdk6+/+ cells with a CDK6-MAZ ChIP peak. (I) Experimental design of siRNA MAZ knockdown assay in sorted Cdk6+/+LSK cells ± palbociclib treatment and in Cdk6KM/KM LSK cells. (J-K) Flow cytometry analysis of (J) HSC/MPP1 scramble cells and (K) HSC/MPP1 cell subset of LSK cells upon MAZ knockdown ± palbociclib treatment depicted as Log2FC relative to corresponding scramble controls (n = 4 per genotype, mean ± SEM). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P< .01.

To assess whether CDK6 and MAZ interplay at chromatin, we reanalyzed publicly available chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data sets from transformed B cells.10,27 A total of 9501 binding sites were identified as common peaks for CDK6 and MAZ (Figure 5E-F). The associated CDK6-MAZ bound genes enriched for pathways related to chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, and apoptotic signaling (supplemental Figure 5B).

The overlap of CDK6-MAZ binding sites with Cdk6KM/KM genes upregulated in the HSC subcluster of Figure 1E identified that ∼50% of all genes display a common binding site (Figure 5G). Among these 282 genes, several are known HSC mediators (Figure 5H).17,18,22,28

Palbociclib (CDK4/6 kinase inhibitor) treatment did not affect MAZ interaction with the promoters of Mlec, Fosb, and Hmgb2 in Cdk6+/+ HPCLSK cells (supplemental Figure 5C). However, CDK6 kinase activity influences the transcription of Mlec and Fosb, which is abrogated by MAZ knockdown (siMAZ) (supplemental Figure 5D).

MAZ knockdown was performed in sorted LSK cells from Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM mice (Figure 5I; supplemental Figure 5E). Cdk6KM/KM cells responded with a decrease in HSC/MPP1 cells compared with controls (Figure 5J-K). Palbociclib-treated Cdk6+/+ LSK cells with siMAZ yielded comparable results and reduced HSC/MPP1 numbers. The LSK fraction remained unaltered in the different conditions (supplemental Figure 5F). In summary, these data indicate a critical role of the kinase-inactivated CDK6-MAZ axes for HSC maintenance.

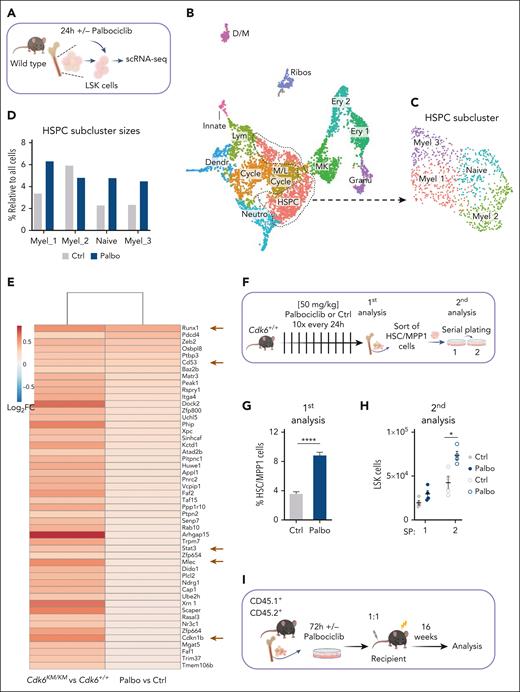

CDK4/6 kinase inhibition protects HSC fitness

We used palbociclib to evaluate its effects on Cdk6+/+ LSK cells by using 10x Genomics scRNA-Seq (Figure 6A).

CDK4/6 kinase inhibition protects HSC fitness. (A) Experimental scheme of 10x Genomics scRNA-seq including flow cytometry sorting of LSK cells followed by 24-hour cultivation with either PBS or palbociclib. (B) UMAP visualization of 13 LSK cell clusters. Colors indicate different clusters. (C) UMAP of 4 HSPC subclusters. Myel 1: granulocyte; Myel 2: dendritic; Myel 3: neutrophil; and Naïve: immature cells. (D) Bar chart of relative HSPC subcluster sizes of the PBS or palbociclib-treated samples. (E) Heat map of top 50 upregulated genes upon palbociclib treatment compared with controls out of the 282 genes found in Figure 5G. Errors indicate top genes of Figure 5H, also found in the palbociclib comparison. (F) Experimental design to assess in vivo palbociclib treatment followed by an in vitro serial plating assay of sorted HSC/MPP1 cells. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of HSC/MPP1 cells and (H) serially plated LSK cell numbers upon in vivo palbociclib treatment (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). (I) Experimental design for competitive BM transplantation assay. CD45.1+ control and palbociclib-treated (200 nM) CD45.2+ BM cells were transplanted in a 1:1 ratio into lethally irradiated recipient mice upon 72 hours of cultivation. (J-K) End point analysis of engrafted BM LSK and HSC/MPP1 cells upon palbociclib treatment (n = 7 per group, mean ± SEM). (L) Experimental overview of PBS or palbociclib-treated human CD34+ cells followed by a serial plating assay. (M-N) Percentage of CD34+CD38– cells and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD34+ cells in 2 serial plating rounds (n = 3-4 per treatment, mean ± SEM). Cycle, cell cycle; Dendr, dendritic; D/M, dendritic/macrophage; Ery, erythroid; Granu, granulocyte; Innate, innate lymphocyte; MK, megakaryocyte; M/L cycle, myeloid/lymphoid cell cycle; Neutro, neutrophil; Ribos, ribosomes; Ctrl, control. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01: ∗∗∗P< .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

CDK4/6 kinase inhibition protects HSC fitness. (A) Experimental scheme of 10x Genomics scRNA-seq including flow cytometry sorting of LSK cells followed by 24-hour cultivation with either PBS or palbociclib. (B) UMAP visualization of 13 LSK cell clusters. Colors indicate different clusters. (C) UMAP of 4 HSPC subclusters. Myel 1: granulocyte; Myel 2: dendritic; Myel 3: neutrophil; and Naïve: immature cells. (D) Bar chart of relative HSPC subcluster sizes of the PBS or palbociclib-treated samples. (E) Heat map of top 50 upregulated genes upon palbociclib treatment compared with controls out of the 282 genes found in Figure 5G. Errors indicate top genes of Figure 5H, also found in the palbociclib comparison. (F) Experimental design to assess in vivo palbociclib treatment followed by an in vitro serial plating assay of sorted HSC/MPP1 cells. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of HSC/MPP1 cells and (H) serially plated LSK cell numbers upon in vivo palbociclib treatment (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). (I) Experimental design for competitive BM transplantation assay. CD45.1+ control and palbociclib-treated (200 nM) CD45.2+ BM cells were transplanted in a 1:1 ratio into lethally irradiated recipient mice upon 72 hours of cultivation. (J-K) End point analysis of engrafted BM LSK and HSC/MPP1 cells upon palbociclib treatment (n = 7 per group, mean ± SEM). (L) Experimental overview of PBS or palbociclib-treated human CD34+ cells followed by a serial plating assay. (M-N) Percentage of CD34+CD38– cells and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD34+ cells in 2 serial plating rounds (n = 3-4 per treatment, mean ± SEM). Cycle, cell cycle; Dendr, dendritic; D/M, dendritic/macrophage; Ery, erythroid; Granu, granulocyte; Innate, innate lymphocyte; MK, megakaryocyte; M/L cycle, myeloid/lymphoid cell cycle; Neutro, neutrophil; Ribos, ribosomes; Ctrl, control. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01: ∗∗∗P< .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

The integrated data identified 13 individual clusters, which we annotated according to published marker gene expression (Figure 6B; supplemental Figure 6A).17,18 We further substructured the HSPC cluster and annotated 4 either immature (naïve) or differentiation-prone cell states (Figure 6C; supplemental Figure 6B).17,18 Consistent with the Cdk6KM/KM HSC subcluster (Figure 1D), the palbociclib-treated sample showed a relative increase in cell number of the naïve subcluster compared with control (Figure 6D). To study the above-defined HSC mediators regulated by CDK6 and MAZ (Figure 5G-H), we analyzed the expression of these genes in the naïve subcluster (Figure 6E; supplemental Figure 6C). Top genes identified in Figure 5H, including Runx1, Cd53, Stat3, Mlec, and Cdkn1b, were found among the top upregulated genes in the naïve palbociclib-treated subcluster relative to controls.

To compare palbociclib-treated LSK cells with CDK6 kinase-inactive cells, we performed an in vivo homing assay. CD45.2+Cdk6+/+ LSK cells pretreated with palbociclib or the control treatment were injected IV into CD45.1+ recipient mice (supplemental Figure 6D-E). At 18 hours after injection, significantly more HSC/MPP1 cells homed in the BM of mice pretreated with palbociclib, whereas LSK cells remained unchanged. MPP2 cells were increased upon palbociclib treatment, whereas MPP3-4 cells were unaltered.

To validate the effects of CDK6 kinase inhibition on the colony-forming potential of HSPCs, we performed serial plating assays with palbociclib (supplemental Figure 6F). Palbociclib treatment resulted in increased colony and LSK cell numbers and decreased differentiated cells from the second round of plating onward.

In vivo treatment with palbociclib every 24 hours over 10 days resulted in a higher percentage of HSC/MPP1-MPP2 cells and reduced MPP 3/4 cells in the BM (Figure 6F-G; supplemental Figure 6G-H). Reduced Myel cells in the BM confirmed the effectiveness of the treatment (supplemental Figure 6I)29. HSC/MPP1 cells were embedded for a serial plating assay. Upon the second round of plating, colony and LSK cell numbers of palbociclib-treated mice were enhanced (Figure 6H; supplemental Figure 6J-K).

In combination with a MAZ knockdown, the colony numbers were reduced in the palbociclib and control conditions, whereas the LSK cells were reduced in the palbociclib samples (supplemental Figure 6L-M).

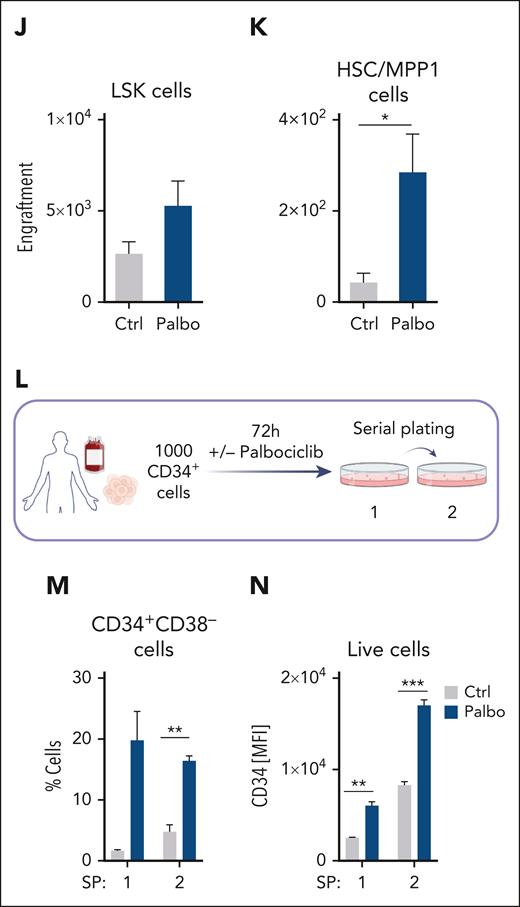

Further, we treated freshly isolated LSK cells either with palbociclib (CD45.2) or PBS (CD45.1) for 72 hours and injected them in a 1:1 ratio into lethally irradiated recipient mice (Figure 6I). After 16 weeks, palbociclib-treated HSC/MPP1 cells showed a competitive advantage (Figure 6J-K; supplemental Figure 6N-O).

To test the effect of palbociclib in a human setting, CD34+ cord blood cells were plated with either palbociclib or control in methylcellulose for serial plating assays (Figure 6L). CD34+CD38– cells were enriched with palbociclib (Figure 6M-N). The percentage of CD11b+ cells was unaltered (supplemental Figure 6P).

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that sustaining kinase-independent functions of CDK6 in HSCs enables enhanced long-term capacity, which is reflected in a specific transcriptional pattern. Kinase-inactivated CDK6 regulates quiescent and activated stem cell gene sets at least partially with NFY-A and MAZ.

Discussion

The function of the hematopoietic system critically depends on the supply of new cells, which are generated as needed by activation of the HSCs. Many patients suffer from hematopoietic deficiencies, but we lack knowledge of when and how to intervene. HSCT is a potentially curative therapy for various hematopoietic diseases. To enhance the success rate of HSCT, we need to maintain stem cell potential and/or improve homing efficiency.

Homing is one of the multiple processes involved in engraftment, which seems to be partially influenced by CDK6.30 We propose that CDK4/6 kinase inhibitors could be used to maintain cultured HSCs in their noncycling and naïve state before they are transferred to the recipient. Although the canonical functions of both CDK4 and CDK6 are inhibited, the kinase-independent functions of CDK6 are generally unaffected or even improved. CDK4/6 inhibitors cause a transient arrest of the cell cycle in HSCs, thereby shielding them from chemotherapy-induced damage.31 We suggest that CDK4/6 inhibitors could be used to treat donor-derived HSCs before HSCT to inhibit their proliferation while improving their regeneration and homing potential.

Critical functions of CDK6 have been described in human cord blood cells. CDK6-enforced expression in long-term HSCs leads to increased cell division, and those cells acquire a competitive advantage that is suggested to be independent of cyclin expression.32 Loss of CDK6 in HSCs inhibits the cells’ exit from dormancy upon activation.13 We now demonstrate that kinase-inactivated CDK6 influences the transcription of a set of genes to enhance HSC functionality upon long-term activation. These kinase-independent functions of CDK6 might partially explain the effects of long-term HSCs with enforced CDK6 expression, when cyclins are not yet expressed.32,33 Loss of CDK6 in HSCs shows the opposite effect.

Hu et al found a 50% reduction in LSK cells of Cdk6–/–- and Cdk6KM/KM mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice,14 whereas our analysis failed to detect these differences. This could be caused by stem cells antigen-1 (Sca-1) expression changes. Sca-1 has previously been recognized to react to certain biological stresses,19 including mouse rearing facilities, with different environmental background in a similar way to the mouse genetic background.

CDK6 does not contain a DNA-binding domain, but exerts its effects by interacting with transcription factors. We have identified the transcription factors with which CDK6 interacts to determine HSC self-renewal. Consistent with our data on leukemic cells,10 CDK6 interacts with NFY-A in a kinase-dependent manner. The CDK6-NFY-A complex induces a gene set that characterizes activated HSCs. CDK6 and CDK2 phosphorylate the DNA-binding domain of NFY-A.10,33,34 We have shown that CDK6 interacts with NFY-A in Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6KM/KM HSPCs. We postulate that kinase-inactivated CDK6 inhibits NFY-A by interacting with it and preventing its phosphorylation, thereby blocking the transcription of NFY-A–dependent genes and suppressing the progression of HSCs to activated MPP1 cells. Knocking down NFY-A in HSCs with kinase-inactivated CDK6 leads to an increase in apoptosis, which was not observed in HSCs with wild type or lacking CDK6. This might be explained by the fact that both proteins regulate p53-response,10,24,25 and it underlines the importance of the delicate axis of CDK6 and NFY-A in activated progenitor cells.

The transcription pattern of Cdk6KM/KM HSCs upon transplantation directs the cells to a more quiescent state. The HSC maintenance axis is characterized by a regulating complex including CDK6 and MAZ. The critical role of kinase-inactivated CDK6 and MAZ interaction is supported by MAZ knockdown experiments in HSCs, as HSCs lose their self-renewal ability.

ChIP-Seq data of CDK6 and MAZ from leukemic B cells reveal a large set of common target genes, showing that the role of CDK6 and MAZ is not restricted to healthy hematopoietic cells. We speculate that the effect on MAZ might be due to a scaffolding function or to the blockage of certain phosphorylation sites that are critical for transcriptional inactivation or chromatin release. Similar to CCCTC-Binding Factor (CTCF), MAZ interacts with a subset of cohesins to organize the chromatin.35

The transcription factor MAZ provides another possibility to balance differentiation. MAZ binds the promoters of genes related to erythroid differentiation. It is highly expressed in several cancers and regulates angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), another known CDK6 target.7,9,36-39 MAZ is also a cofactor of CTCF in embryonic stem cells, where it insulates active chromatin at Hox clusters during differentiation.37 This function could explain the bias toward Myel-directed differentiation in Cdk6KM/KM HSPCs, which suggests that CDK6 regulates Hox genes and thereby differentiation together with MAZ and CTCF. We thus have evidence for a role of CDK6 in regulation, not only in the most naïve HSC compartment but also in early hematopoietic progenitors.

Our data indicate a regulation of NFY-A and MAZ by CDK6, which is important for the long-term repopulation capability of HSCs. Our results present a strategy to enhance the success of HSCTs by pretreating HSCs with CDK4/6 kinase inhibitors. CDK4/6 kinase inhibitors are used and tested for combinatorial cancer therapy.7,40 These treatments might improve the fitness of healthy HSCs as a byproduct of cancer therapy. We highlight CDK6 as a major player in HSPCs, and inactivation of the CDK6 kinase domain thus has dramatically different consequences compared with the complete loss of CDK6. Regarding the upcoming protein degrader strategies, it is crucial for future clinical trials to consider our data showing reduced HSC potential in HSCs lacking CDK6.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Ensfelder-Koperek, P. Kudweis, S. Fajmann, P. Jodl, D. Werdenich, and I. Dhrami for excellent technical support; G. Tebb for his excellent knowledge and support in scientific writing; M. Milsom and F. Grebien for scientific discussions; U. Ma for great technical support and the FACS facility MedUni Vienna for experimental support; and the Biomedical Sequencing Facility at CeMM for next-generation sequencing library preparation, sequencing, and related bioinformatics analyses. This research was supported using resources of the VetCore Facility (Mass Spectrometry) of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna. Graphics were created with BioRender.com

This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 694354). This research was funded in whole or in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (SFB-F6101, P 31773).

Authorship

Contribution: I.M.M., E.D., T.K., V.S., and K.K. conceptualized the study; T.K., M.Z., R.G., and G.H. conducted formal analyses; I.M.M., E.D., S.K., L.G., M.P.-M., A.S., L.S., and M.F. performed experiments; U.M., L.E.S., and N.K provided technical support; M.M., A.F., and E.Z.-B. provided resources; I.M.M., E.D., T.K., and K.K. were responsible for writing of the manuscript; and V.S. and K.K. provided supervision.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Karoline Kollmann, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Veterinärplatz 1, 1210 Vienna, Austria; email: karoline.kollmann@vetmeduni.ac.at.

References

Author notes

All sequencing data are avaliable via ArrayExpress with the following accession numbers: E-MTAB-13145 (low-input RNA-seq), E-MTAB-13149 (LSK scRNA-seq) and E-MTAB-13268 (Palbociclib LSK cell scRNA-seq).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![CDK6 shapes the HSC transcriptomic landscape in a kinase-inactivated, kinase-dependent, and -independent manner. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of isolated BM from Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM mice. Cell numbers of HSCs (LSK [Lin–Sca-1+c-kit+] CD34–CD48–CD150+CD135–), MPP1 (LSK CD34+CD48–CD150+CD135–), MPP2 (LSK CD48+CD150+), and MPP 3/4 (LSK CD48+CD150–) (n = 10; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (B) Experimental scheme of 10x Genomics scRNA-seq including flow cytometry sorting of LSK cells of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM BM (top). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of 11 LSK cell clusters (bottom). Colors indicate different clusters. (C) UMAP of 9 HSPC subclusters with color code. (D) Bar chart of HSPC subcluster size differences of either Cdk6–/– or Cdk6KM/KM compared with the Cdk6+/+ control (Log2FC of percent cluster sizes relative to Cdk6+/+). (E) UMAP of Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSPC cluster. The arrow indicates HSC subcluster. (F) Classification of CDK6 states: kinase-inactivated, kinase-dependent, and loss of CDK6 (top). Venn diagrams showing number of genes of the HSC subcluster uniquely (bottom) or commonly upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) in Cdk6KM/KM and Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ (|Log2FC| ≥ 0.3). (G) UMAP showing Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSPCs overlaid with the HSC–associated proliferation gene signature (Psig).16 The 15% of cells with the lowest Psig score (compare methods) are indicated in blue. Violin plots depict Psig and HSC–associated quiescent signature (Qsig) of all 3 genotypes. Cycle, cell cycle; Ery, erythroid; Rep, replication. ∗P < .05.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/2/10.1182_blood.2023021985/2/m_blood_bld-2023-021985-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1769098949&Signature=PqyePxrFvyWx~8LV-u8SApHlwCCZKf~Ap4SGS2DLzmheciUlot-rwWufCpCQ9NgfxlxfW4vHTO~mDt0k3bLecyMwHr~vxWoGiVYcG0OL4TELzSVgAfw1Xlww~TY5E75OYbmbW7Z-sfgvQgeWeimVMxgZR~dP6H5bO4qSr4w~EDs6V8YsvwQ~5YSu3x7SwutH4fjwsiKHrIsP-uoj0KuhcrYEE7NFYwDwnmd2Vr8BRyyb8RBCmGty6pk~S8CmhQLUyh~4MC7~tekFJemVoIuY4qj97MVZMDfk9thdIsmWdFkyJuyzX1JdxrwuBz0oVUnwunfAoxdQOJ~IZmaZka1aLg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Kinase-inactivated CDK6 and MAZ influence HSC maintenance. (A-B) Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis of genes within the quiescent stem cell gene set that are either upregulated in (A) Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ cells or (B) Cdk6–/– compared with Cdk6+/+ cells after 2 serial rounds of transplantation. (C) CDK6 interactome analysis generated by nuclear CDK6-IP mass spectrometry analysis of HPC-7 cell lines expressing either wild-type CDK6 or CDK6KM. Dot plot illustrating all protein interactions with CDK6 or CDK6KM vs CDK6–/– (Log2FC). Established CDK6 interactors are highlighted in blue. Transcription factors interacting with CDK6KM and analyzed from the CDK6KM specific motif analysis from supplemental Figure 5A are highlighted in red. (D) Flow cytometry proximity ligation assay of CDK6 and MAZ antibodies showing endogenous protein interaction in ex vivo Cdk6+/+, Cdk6–/–, and Cdk6KM/KM HSC/MPP1 cells. Representative flow cytometry histograms are depicted on the right. Cdk6–/– cells, MAZ, and CDK6 antibody only samples served as controls. (E) Overlap of CDK6 ChIP-seq data from BCR/ABLp185+ cells with published MAZ ChIP-seq data from CH12.LX mouse lymphoma cell line. (F) Annotation of the genomic regions identified in the CDK6/MAZ ChIP-seq overlap. (G) CDK6/MAZ ChIP-seq overlay (+2 kb to –500 bp to transcription start site [TSS]) with upregulated genes of Cdk6KM/KM compared with Cdk6+/+ dormant HSC subcluster genes (scRNA-seq FC ≥ 0.3). (H) Stem cell genes of Cdk6KM/KM or Cdk6–/– cells compared with Cdk6+/+ cells with a CDK6-MAZ ChIP peak. (I) Experimental design of siRNA MAZ knockdown assay in sorted Cdk6+/+LSK cells ± palbociclib treatment and in Cdk6KM/KM LSK cells. (J-K) Flow cytometry analysis of (J) HSC/MPP1 scramble cells and (K) HSC/MPP1 cell subset of LSK cells upon MAZ knockdown ± palbociclib treatment depicted as Log2FC relative to corresponding scramble controls (n = 4 per genotype, mean ± SEM). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P< .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/2/10.1182_blood.2023021985/2/m_blood_bld-2023-021985-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1769098949&Signature=p3XbV5NbHH2LLbdKnsDE5KWMN5SaXm7cW5adMA2~0MKm5-TOtdG7SsLpxvZMwMJxKWtZmct4pLPus8Npa-d0WTcgPvtO~IJ4qLJNjGPz7HMrWanFn7gj1xo3EOmkvYT7xpQe69xLeMLrPwjlTF9Mh9bJlrTEkoRwjDtgBvK8cfjl2aY~VFIwcDey4lo3uzMJA-Qh7bd7O53Ij9aWYoZuypxYNyKJjT9aIi1oubqzfRF5cJwL5KFb3Qf5tLCHuCcEMimYiphIBkx4uarY6pQWuKeADAk2FynbJP1Tmve56QSf1f-0RO3P4Mx6qlRrLaPM9RF76Ao7uta1d35eOdyRpw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal