Key Points

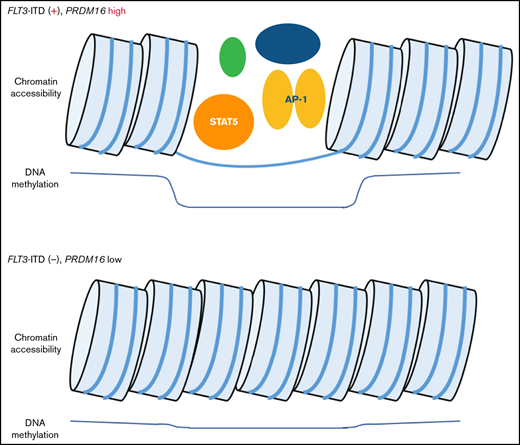

FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 expression induced methylation changes at STAT5 and AP-1 binding sites in pediatric AML.

Hypomethylated regions in PRDM16-highly expressed AMLs were correlated with enhanced chromatin accessibilities at multiple genomic regions.

Abstract

We investigated genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in 64 pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Based on unsupervised clustering with the 567 most variably methylated cytosine guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites, patients were categorized into 4 clusters associated with genetic alterations. Clusters 1 and 3 were characterized by the presence of known favorable prognostic factors, such as RUNX1-RUNX1T1 fusion and KMT2A rearrangement with low MECOM expression, and biallelic CEBPA mutations (all 8 patients), respectively. Clusters 2 and 4 comprised patients exhibiting molecular features associated with adverse outcomes, namely internal tandem duplication of FLT3 (FLT3-ITD), partial tandem duplication of KMT2A, and high PRDM16 expression. Depending on the methylation values of the 1243 CpG sites that were significantly different between FLT3-ITD+ and FLT3-ITD− AML, patients were categorized into 3 clusters: A, B, and C. The STAT5-binding motif was most frequently found close to the 1243 CpG sites. All 8 patients with FLT3-ITD in cluster A harbored high PRDM16 expression and experienced adverse events, whereas only 1 of 7 patients with FLT3-ITD in the other clusters experienced adverse events. PRDM16 expression levels were also related to DNA methylation patterns, which were drastically changed at the cutoff value of PRDM16/ABL1 = 0.10. The assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing of AMLs supported enhanced chromatin accessibility around genomic regions, such as HOXB cluster genes, SCHIP1, and PRDM16, which were associated with DNA methylation changes in AMLs with FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 expression. Our results suggest that DNA methylation levels at specific CpG sites are useful to support genetic alterations and gene expression patterns of patients with pediatric AML.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clinically and biologically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy that is characterized by cytogenetic abnormalities, including fusion genes, mutations, epigenetic modifications, and dysregulated gene expression.1,2 For example, the strong expression levels of MECOM (also known as EVI1) and its homolog, PRDM16 (also known as MEL1), have been reported to be associated with inferior outcomes in our pediatric patients with AML.3,4 Because of this genetic heterogeneity, accurate prognostic predictions for patients with AML are difficult to obtain. Therefore, novel biomarkers are needed to elucidate the clinical characteristics of patients with this clinically heterogeneous disease.

Aberrant DNA methylation has been detected in adult patients with AML, and particular methylation patterns have been associated with cytogenetic abnormalities and prognosis.5-8 However, only a few reports have discussed the influence of DNA methylation status on the clinical features of pediatric AML,9 and the significance of this potential biomarker remains unclear. Most previous studies have analyzed only the DNA methylation status of promoter regions, although some reports suggest the importance of DNA methylation in other regions, particularly in the gene body.10,11 In contrast to gene expression analysis, DNA methylation analysis is considered highly credible because it provides excellent quantitative determinations and absolute values, without requiring endogenous controls. Therefore, we analyzed genome-wide DNA methylation in 64 pediatric patients with AML to reveal the differences in DNA methylation patterns among various cytogenetic alterations, particularly in PRDM16 expression value, and investigate the associations of methylation patterns with other genetic alterations.

Patients and methods

Patients

A total of 64 pediatric patients with de novo AML (age range, 0-17 years) treated in the Japanese AML-05 trial were enrolled in this study. The AML-05 trial was conducted by the Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group between November 2006 and December 2010 (registered at http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm as #UMIN000000511), and details of the treatment were described in another report.12 The clinical characteristics of the 64 patients are shown in supplemental Table 1. All treatment methods, data, and sample collection protocols in the clinical trial were approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents/guardians. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of Gunma Children’s Medical Center, Yokohama City University Hospital, and the ethical review board of the Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group.

DNA methylation analysis

All leukemic samples were obtained from bone marrow at diagnosis and were cell preserved using Ficoll separation where blast cells were enriched. DNA samples from all 64 pediatric patients with AML were prepared using the ALLPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). After adjusting the concentration of each DNA sample to 250 ng/μL, a comprehensive DNA methylation analysis was performed using the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Methylation data were obtained in an IDAT file format with the iScan System (Illumina) and then processed using the RnBeads package (https://bioconductor.org/biocLite.R)13 in R software (version 3.4.3). The data were normalized using the Illumina method in the RnBeads package, and the manifest file was annotated using IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b2.hg19. We removed 3828 unreliable probes by using a greedy approach, as well as 2932 non–cytosine guanine dinucleotide (CpG) targeting probes. We also filtered 18 926 probes located on the X or Y chromosome and 17 240 single nucleotide polymorphism–related probes. Finally, we obtained 757 561 autosomal probes from 64 samples. We classified DNA methylation levels into 3 groups according to their β value: hypermethylation (≥0.67), intermediate methylation (0.34-0.66), and hypomethylation (≤0.33), respectively.

Assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing

We performed an assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) using 5 other samples from pediatric patients with AML who were not registered in the AML-05 study but were treated at Yokohama City University Hospital (supplemental Table 2).

Cells were harvested and frozen in culture media containing CELLBANKER 1 (ZENOAQ, Fukushima, Japan). Cryopreserved cells were sent to Active Motif to perform ATAC-seq. The cells were then thawed in a 37°C water bath, pelleted, washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline, and tagmented as previously described,14 with some modifications based on Corces et al.15 Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer, pelleted, and tagmented using the enzyme and buffer provided in the Nextera Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Tagmented DNA was then purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen), amplified with 10 cycles of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and purified using Agencourt AMPure SPRI Beads (Beckman Coulter). Resulting material was quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina platforms (KAPA Biosystems) and sequenced with PE42 sequencing on the NextSeq 500 Sequencer (Illumina).

Reads were aligned using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner algorithm (MEM mode; default settings). Duplicate reads were removed; only reads mapping as matched pairs and only uniquely mapped reads (mapping quality ≥1) were used for further analysis. Alignments were extended in silico at their 3′ ends to a length of 200 bp and assigned to 32-nt bins along the genome. The resulting histograms (genomic signal maps) were stored in bigWig files.

Screening for molecular characterization

The molecular characterization included mutational analyses of internal tandem duplication of FLT3 (FLT3-ITD), NPM1 (exon 12), WT1 (exons 7-10), and all coding regions of CEBPA, DNMT3A, TET2, and IDH1/216-22 ; gene rearrangement analyses of KMT2A, RUNX1-RUNX1T1, CBFB-MYH11, NUP98-NSD1, and FUS-ERG (reverse transcription PCR); and an analysis of KMT2A partial tandem duplication (multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification methods).23,24 GeneScan (Applied Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan) was used to determine the allele ratio of FLT3-ITD to the wild-type alleles; here, allele ratio values of >0.7 and ≤0.7 were defined as high and low, respectively, according to a previous report.25 We also performed quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis of PRDM16 and MECOM expression and defined the following respective cutoff points according to the results of receiver operating characteristic curve in the previous report: PRDM16/ABL1 ratio ≥0.10 and MECOM/ABL1 ratio ≥0.10.3

Transcriptome analysis

We performed transcriptome analysis in 45 of 64 patients to investigate the relationship between DNA methylation patterns and gene expression, which was performed according to the methods described in a previous report.26

Transcription factor–binding site analysis

Transcription factor (TF) motifs were found by HOMER (version 4.11) with Finding Enriched Motifs in Genomic Regions using the default setting.27

Use of a public database

We compared the DNA methylation data and expression data of our cohort with those of the National Cancer Institute TARGET cohort in the public database. The public data included 91 pediatric patients with AML analyzed using a 450K methylation array. Of these, only 8 cases had expression data. The public database was available at https://target-data.nci.nih.gov/Public/AML/.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR software (version 1.36; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan).28 All P values were 2 tailed, and a P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Detailed statistical methods are described in the data supplement. Analysis of variance was used to assess the differences between groups in mean age and white blood cell count at diagnosis. The χ2 test was applied to comparisons of other factors. Overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival were compared using the log-rank test. OS was defined as the time interval from diagnosis to death or last follow-up, whereas EFS was defined as the time interval from diagnosis to the date of treatment failure (induction failure, relapse, second malignancy, or death) or the date of last contact, whichever was appropriate. For methylation analysis, P values were determined using a 2-sided Welch’s t test, and a false discovery rate–adjusted P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Clustering was performed using the complete linkage method. CpG-associated genes were determined by the Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT [version 4.0.4]) if transcription start sites (TSSs) were located between 1 megabase upstream or downstream of the concerned CpG. Significant terms were selected when the false discovery rate–adjusted P value was <.05 by both binomial and hypergeometric tests.

Results

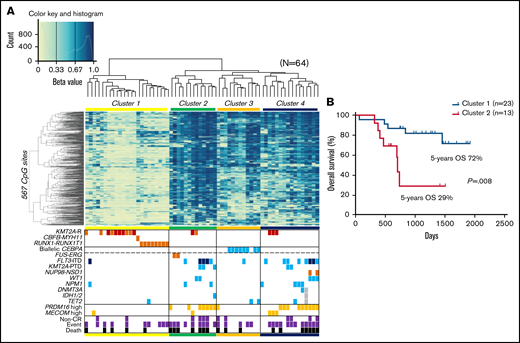

Clustering in the DNA methylation analysis was consistent with molecular features

We analyzed 757 561 methylation sites per sample, collected from our cohort of 64 pediatric patients with AML. To identify the differences in DNA methylation across samples, we selected 567 CpG sites that showed the most variable methylation values among 64 AMLs (standard deviation >0.3; supplemental Table 3). An unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis based on the methylation values at these sites generated 4 clusters of AML (clusters 1-4; Figure 1A). Clusters 1 and 2 consisted of AMLs that exhibited lowest and highest methylation levels, respectively. Clusters 3 and 4 corresponded to intermediate methylation levels. Cluster 2 had a significantly worse OS than cluster 1 (P = .008; Figure 1B). Distributions of FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 expression were significantly unequal (P = .003 and P < .001, respectively), with high frequencies in clusters 2 and 4 and low frequencies in clusters 1 and 3. Patients in clusters 2 and 4 tended to be older and have a higher white blood cell count at diagnosis and a higher mortality rate than patients in clusters 1 and 3 (supplemental Table 4). Cluster 1 was characterized by the presence of known favorable prognostic factors, such as RUNX1-RUNX1T1 fusion and KMT2A rearrangement with low MECOM expression.29 All patients with biallelic CEBPA mutations, which indicated a favorable outcome, were classified under cluster 3. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering with methylation values of CpG sites that showed the most variable methylation values among our 64 AMLs succeeded in dividing biallelic CEBPA mutations and RUNX1-RUNX1T1 fusion in publicly available TARGET data (supplemental Figure 1).

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of DNA methylation profiles and associations between DNA methylation clusters and additional parameters. (A) Heatmap of the DNA methylation profiles of 64 AMLs based on unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Clustering was based on the 567 CpG sites with the most variable methylation values in the 64 studied cases. Four clusters were generated: 1, 2, 3, and 4. DNA methylation levels were classified into 3 groups according to their β value: hypermethylation (≥0.67), intermediate methylation (0.34-0.66), and hypomethylation (≤0.33), respectively. Light blue, orange, and dark orange indicate the presence of the specified mutation, high gene expression, and chromosomal aberration, respectively. Brown indicates KMT2A-MLLT3 fusion, and dark blue indicates FLT3-ITD with high allele ratio (>0.7). Purple and black indicate non–complete remission (CR) and events and deaths, respectively. (B) Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves of OS between clusters 1 and 2. KMT2A-R, KMT2A rearrangement; PTD, partial tandem duplication.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of DNA methylation profiles and associations between DNA methylation clusters and additional parameters. (A) Heatmap of the DNA methylation profiles of 64 AMLs based on unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Clustering was based on the 567 CpG sites with the most variable methylation values in the 64 studied cases. Four clusters were generated: 1, 2, 3, and 4. DNA methylation levels were classified into 3 groups according to their β value: hypermethylation (≥0.67), intermediate methylation (0.34-0.66), and hypomethylation (≤0.33), respectively. Light blue, orange, and dark orange indicate the presence of the specified mutation, high gene expression, and chromosomal aberration, respectively. Brown indicates KMT2A-MLLT3 fusion, and dark blue indicates FLT3-ITD with high allele ratio (>0.7). Purple and black indicate non–complete remission (CR) and events and deaths, respectively. (B) Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves of OS between clusters 1 and 2. KMT2A-R, KMT2A rearrangement; PTD, partial tandem duplication.

DNA methylation patterns predicted the outcomes of patients with FLT3-ITD

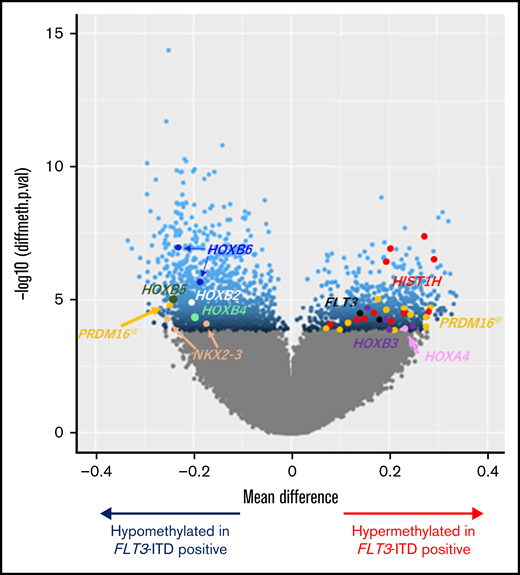

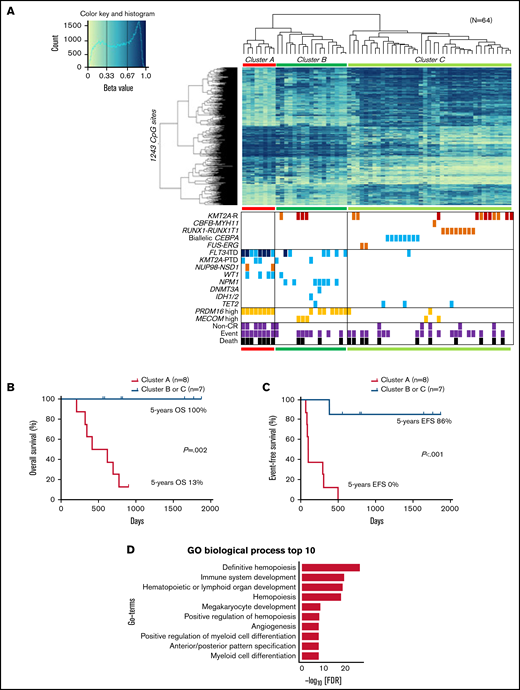

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering divided patients with AML with FLT3-ITD and/or high PRDM16 expression into clusters 2 and 4 (Figure 1A). Therefore, we sought CpG sites with methylation values that differed significantly between patients with and without FLT3-ITD. Consequently, we identified significantly different methylation values at 2501 CpG sites in patients with FLT3-ITD, in comparison with others. The hypermethylation of HOXB3 (5′ untranslated region [UTR]), HOXA4 (TSS200), FLT3 (body), and PRDM16 (body) and the hypomethylation of HOXB2 (TSS1500), HOXB4 (TSS1500), HOXB5 (TSS1500, TSS200, body, and 3′ UTR), HOXB6 (TSS200, body, and 3′ UTR), and NKX2-3 (body and 3′ UTR) were observed in patients harboring FLT3-ITD (Figure 2). Patients with FLT3-ITD showed a significantly higher expression of FLT3 than those without FLT3-ITD (P = .022; supplemental Figure 2). This result was consistent with a previous report that demonstrated that hypermethylation of the gene body was associated with high gene expression.30 Furthermore, 11 CpG sites located in HIST1H that regulate the transcription of individual genes by bundling histone octamers via DNA methylation exhibited significant hypermethylation in patients harboring FLT3-ITD (Figure 2). The HOX family of genes is reported to be expressed in FLT3-ITD/NPM1–specific TF networks.31 Depending on the methylation values of the 1243 CpG sites that were significantly different between FLT3-ITD+ and FLT3-ITD− AMLs, patients were categorized into 3 clusters (Figure 3A). Cluster A was composed of 8 patients carrying FLT3-ITD, and 4 patients harbored the WT1 mutation. The remaining 7 of the 15 patients with FLT3-ITD were distributed in cluster B or C. All 8 patients with FLT3-ITD+ in cluster A experienced events, whereas only 1 of 7 patients with FLT3-ITD+ in cluster B or C experienced events (Figure 3A; Table 1). According to the survival analysis between patients with FLT3-ITD in clusters A and B or C, patients in cluster A showed worse prognosis than those in the other clusters (5-year OS, 13% vs 100%; P = .002 and 5-year EFS, 0% vs 86%; P < .001; Figure 3B-C). Remarkably, all patients in cluster A expressed high levels of PRDM16 (Figure 3A). High PRDM16 expression was significantly more frequent in cluster A than in clusters B (P = .023) and C (P < .001).

Volcano plot comparing the number of significantly hyper- and hypomethylated probes in patients with FLT3-ITD. Mean methylation differences (x-axis) and negative log10-transformed statistical P values (y-axis) between AML with and without FLT3-ITD are shown in the volcano plot. Methylation levels of the 2501 CpG sites were significantly different between the groups at false discovery rate–adjusted P values <.05, which are represented in blue. Dots in other colors correspond to various genes as follows: brown, NKX2-3; white, HOXB2; aquamarine, HOXB4; green, HOXB5; cyan, HOXB6; black, FLT3; red, HIST1H genes (including HIST1H2AE, HIST1H2AJ, HIST1H2BG, HIST1H2BI, HIST1H3E, and HIST1H3J); orange, PRDM16; purple, HOXB3; and pink, HOXA4. Among the 12 dots of PRDM16, 1 CpG site appeared on the hypomethylation side located near the TSS of PRDM16. In contrast, the remaining 11 CpG sites appeared on the hypermethylation side located in the PRDM16 gene body.

Volcano plot comparing the number of significantly hyper- and hypomethylated probes in patients with FLT3-ITD. Mean methylation differences (x-axis) and negative log10-transformed statistical P values (y-axis) between AML with and without FLT3-ITD are shown in the volcano plot. Methylation levels of the 2501 CpG sites were significantly different between the groups at false discovery rate–adjusted P values <.05, which are represented in blue. Dots in other colors correspond to various genes as follows: brown, NKX2-3; white, HOXB2; aquamarine, HOXB4; green, HOXB5; cyan, HOXB6; black, FLT3; red, HIST1H genes (including HIST1H2AE, HIST1H2AJ, HIST1H2BG, HIST1H2BI, HIST1H3E, and HIST1H3J); orange, PRDM16; purple, HOXB3; and pink, HOXA4. Among the 12 dots of PRDM16, 1 CpG site appeared on the hypomethylation side located near the TSS of PRDM16. In contrast, the remaining 11 CpG sites appeared on the hypermethylation side located in the PRDM16 gene body.

Clustering of DNA methylation profiles according to FLT3-ITD. (A) hierarchical clustering analysis with the methylation levels of the 1243 CpG sites with methylation differences of ≥20% generated 3 clusters (A, B, and C), and associations of the DNA methylation cluster according to FLT3-ITD status with mutations, expression levels, cytogenetic features, and outcomes in pediatric patients with AML. DNA methylation levels were classified into 3 groups according to their β value: hypermethylation (≥0.67), intermediate methylation (0.34-0.66), and hypomethylation (≤0.33), respectively. Light blue, orange, and dark orange indicate presence of the specified mutation, high gene expression, and chromosomal aberration, respectively. Brown indicates KMT2A-MLLT3 fusion, and dark blue indicates FLT3-ITD with high allele ratio (>0.7). Gray and black indicate non–complete remission (CR) and events and deaths, respectively. (B-C) Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (B) and EFS (C) between clusters A and B or C of panel A in 15 patients with FLT3-ITD. (D) Gene ontology (GO) biologic process for the top 1243 CpG-related 1481 genes. FDR, false discovery rate; GO, gene ontology; KMT2A-R, KMT2A rearrangement; PTD, partial tandem duplication.

Clustering of DNA methylation profiles according to FLT3-ITD. (A) hierarchical clustering analysis with the methylation levels of the 1243 CpG sites with methylation differences of ≥20% generated 3 clusters (A, B, and C), and associations of the DNA methylation cluster according to FLT3-ITD status with mutations, expression levels, cytogenetic features, and outcomes in pediatric patients with AML. DNA methylation levels were classified into 3 groups according to their β value: hypermethylation (≥0.67), intermediate methylation (0.34-0.66), and hypomethylation (≤0.33), respectively. Light blue, orange, and dark orange indicate presence of the specified mutation, high gene expression, and chromosomal aberration, respectively. Brown indicates KMT2A-MLLT3 fusion, and dark blue indicates FLT3-ITD with high allele ratio (>0.7). Gray and black indicate non–complete remission (CR) and events and deaths, respectively. (B-C) Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (B) and EFS (C) between clusters A and B or C of panel A in 15 patients with FLT3-ITD. (D) Gene ontology (GO) biologic process for the top 1243 CpG-related 1481 genes. FDR, false discovery rate; GO, gene ontology; KMT2A-R, KMT2A rearrangement; PTD, partial tandem duplication.

Clinical characteristics of 15 pediatric patients with AML with FLT3-ITD

| N . | Age, y . | Sex . | WBC, 109/L . | Blast, % . | FLT3-ITD AR . | Cluster . | Other genetic alterations . | PRDM16 expression . | Non-CR . | Relapse . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G_AML_012 | 11.4 | F | 4.5 | 78.4 | 0.71 | A | WT1, KMT2A-PTD | High | + | − | Dead |

| G_AML_136 | 12.8 | M | 7.0 | 76.4 | 0.70 | A | WT1 | High | − | + | Dead |

| G_AML_153 | 7.4 | M | 168.1 | 92 | 0.84 | A | — | High | + | + | Dead |

| G_AML_188 | 10.8 | F | 380.5 | 88.6 | 0.60 | A | — | High | − | + | Dead |

| G_AML_222 | 11.2 | F | 210.3 | 81.1 | 0.48 | A | NUP98-NSD1, WT1 | High | + | − | Dead |

| G_AML_225 | 17.3 | M | 147.9 | 85 | 0.73 | A | NUP98-NSD1, WT1 | High | + | + | Dead |

| G_AML_306 | 10.8 | F | 45.3 | 85.5 | 0.64 | A | KMT2A-PTD | High | + | + | Alive |

| G_AML_381 | 11.8 | M | 70.8 | 87.2 | 4.47 | A | KMT2A-PTD | High | + | + | Dead |

| G_AML_051 | 11.5 | F | 4.5 | 66.5 | 0.30 | B | NPM1 | High | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_105 | 17.5 | F | 65.3 | 89 | 0.63 | B | — | Low | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_319 | 2.8 | M | 17.7 | 95.1 | 0.77 | B | NPM1 | Low | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_329 | 10.6 | F | 4.6 | 44.8 | 0.24 | B | — | High | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_432 | 2.1 | F | 209.0 | 51.6 | 0.38 | B | NPM1 | Low | − | + | Alive |

| G_AML_437 | 16.9 | M | 8.5 | 23.1 | 0.11 | B | NPM1 | High | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_018 | 2.7 | M | 114.4 | 79 | 0.34 | C | — | Low | − | − | Alive |

| N . | Age, y . | Sex . | WBC, 109/L . | Blast, % . | FLT3-ITD AR . | Cluster . | Other genetic alterations . | PRDM16 expression . | Non-CR . | Relapse . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G_AML_012 | 11.4 | F | 4.5 | 78.4 | 0.71 | A | WT1, KMT2A-PTD | High | + | − | Dead |

| G_AML_136 | 12.8 | M | 7.0 | 76.4 | 0.70 | A | WT1 | High | − | + | Dead |

| G_AML_153 | 7.4 | M | 168.1 | 92 | 0.84 | A | — | High | + | + | Dead |

| G_AML_188 | 10.8 | F | 380.5 | 88.6 | 0.60 | A | — | High | − | + | Dead |

| G_AML_222 | 11.2 | F | 210.3 | 81.1 | 0.48 | A | NUP98-NSD1, WT1 | High | + | − | Dead |

| G_AML_225 | 17.3 | M | 147.9 | 85 | 0.73 | A | NUP98-NSD1, WT1 | High | + | + | Dead |

| G_AML_306 | 10.8 | F | 45.3 | 85.5 | 0.64 | A | KMT2A-PTD | High | + | + | Alive |

| G_AML_381 | 11.8 | M | 70.8 | 87.2 | 4.47 | A | KMT2A-PTD | High | + | + | Dead |

| G_AML_051 | 11.5 | F | 4.5 | 66.5 | 0.30 | B | NPM1 | High | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_105 | 17.5 | F | 65.3 | 89 | 0.63 | B | — | Low | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_319 | 2.8 | M | 17.7 | 95.1 | 0.77 | B | NPM1 | Low | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_329 | 10.6 | F | 4.6 | 44.8 | 0.24 | B | — | High | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_432 | 2.1 | F | 209.0 | 51.6 | 0.38 | B | NPM1 | Low | − | + | Alive |

| G_AML_437 | 16.9 | M | 8.5 | 23.1 | 0.11 | B | NPM1 | High | − | − | Alive |

| G_AML_018 | 2.7 | M | 114.4 | 79 | 0.34 | C | — | Low | − | − | Alive |

AR, allele ratio; CR, complete remission; F, female; M, male; PTD, partial tandem duplication; WBC, white blood cell.

The 1243 CpG sites in Figure 3A were allocated to 1481 genes and revealed that these genes were significantly enriched in definitive hemopoiesis and had the lowest P values (Figure 3D; supplemental Table 5). The 9 terms with the next lowest P values were nearly related to lymphocyte, hemopoiesis, and myeloid (Figure 3D). Some of them overlapped with the top enriched gene ontology terms for upregulated genes of FLT3-ITD compared with CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells, which have been reported previously.31

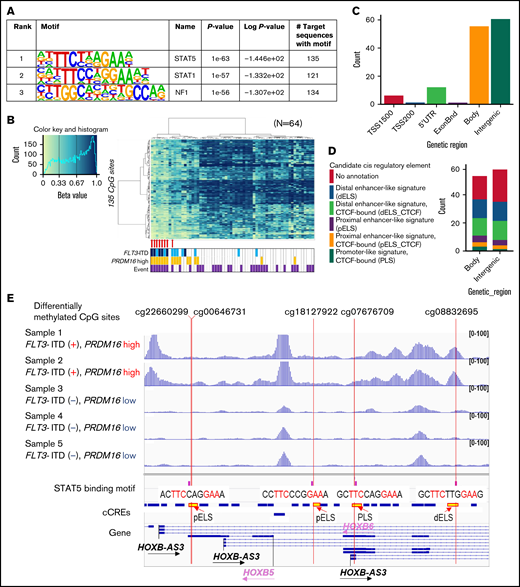

Three TF-binding motifs were significantly enriched in the 1243 CpG sites (Figure 4A). Methylation levels at the 135 CpG sites, near where the top STAT5 motifs were, classified the 8 patients of cluster A in the first trunk (Figure 4B). Of the 135 CpG sites, 85% were located in the gene body or intergenic region (Figure 4C; supplemental Table 6), and 65% were annotated as candidate cis-regulatory elements (Figure 4D).31 ATAC-seq of 5 AMLs (supplemental Table 2) confirmed that genomic regions where DNA methylation changed close to STAT5-binding motifs were specifically opened in 2 AMLs with FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 gene expression (Figure 4E), which may indicate that the detection of aberrant STAT5 activity implies a worse prognosis in patients with FLT3-ITD. In addition, high PRDM16 expression was concentrated in cluster A, which indicated that high PRDM16 expression may affect DNA methylation.

TF-binding motif analysis of genomic regions in which DNA methylation was different between FLT3-ITD+ and FLT3-ITD− AMLs. (A) The 3 TFs were confirmed by HOMER in the genomic regions ±200 bp in length adjacent to each of the 1243 CpG sites with a P value <1e−50. (B) hierarchical clustering of methylation levels at 135 CpG sites in the STAT5-binding sites was classified in 8 patients of cluster A in the first trunk. Eight patients with AML with FLT3-ITD in cluster A in Figure 3A are indicated by red arrows. (C) Genetic localization of 135 CpG sites for which the STAT5-binding motif existed nearby. (D) Annotation of candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) in the gene body and intergenic CpG sites close to STAT5-binding motifs. (E) Chromatin accessibility of the genomic regions where STAT5 binds close to the methylation-changed CpG sites was analyzed in 5 patients using ATAC-seq. Some open chromatin regions in the HOXB-AS3 gene were identified only in patients with FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 gene expression. Annotations of cCREs are described in panel D.

TF-binding motif analysis of genomic regions in which DNA methylation was different between FLT3-ITD+ and FLT3-ITD− AMLs. (A) The 3 TFs were confirmed by HOMER in the genomic regions ±200 bp in length adjacent to each of the 1243 CpG sites with a P value <1e−50. (B) hierarchical clustering of methylation levels at 135 CpG sites in the STAT5-binding sites was classified in 8 patients of cluster A in the first trunk. Eight patients with AML with FLT3-ITD in cluster A in Figure 3A are indicated by red arrows. (C) Genetic localization of 135 CpG sites for which the STAT5-binding motif existed nearby. (D) Annotation of candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) in the gene body and intergenic CpG sites close to STAT5-binding motifs. (E) Chromatin accessibility of the genomic regions where STAT5 binds close to the methylation-changed CpG sites was analyzed in 5 patients using ATAC-seq. Some open chromatin regions in the HOXB-AS3 gene were identified only in patients with FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 gene expression. Annotations of cCREs are described in panel D.

Cutoff values of PRDM16 expression as defined by DNA methylation analysis

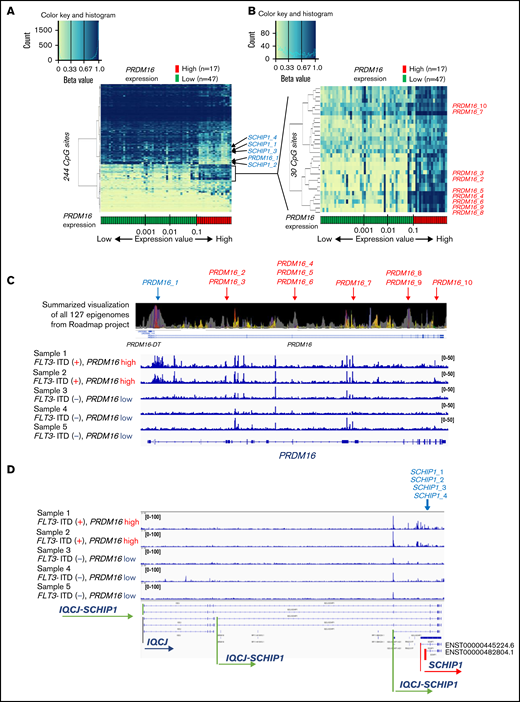

We examined the relationship between PRDM16 expression and DNA methylation status and identified 244 CpG sites wherein methylation status was significantly associated with PRDM16 expression level (supplemental Table 7). The arrangement of the 64 patients according to a series of PRDM16 expression values yielded 2 groups with distinct methylation patterns (Figure 5A). The methylation pattern drastically changed at this border (PRDM16/ABL1 = 0.10). We evaluated various cutoff points to confirm the relationship between the methylation pattern and expression value of PRDM16 (supplemental Figure 3), and the cutoff point we adopted was appropriate. Although the number of samples for annotation of gene expression levels was limited, we reconfirmed that methylation levels at the 244 CpG sites accurately distinguished AMLs with highly expressed PRDM16 in the TARGET data (supplemental Figure 4). Methylation differences at the 244 CpG sites were associated with changes in expression levels, especially in the following genes, in which methylation levels at multiple CpG sites were significantly altered in PRDM16_high AMLs: SCHIP1, HOXB-AS3, HOXB5, and RPS6KL1 (supplemental Figure 5). Figure 5B presents 30 CpG sites that were associated with particularly large differences in direction of hypermethylation values between the 2 groups. Nine of these sites were located at PRDM16 (supplemental Table 7). Remarkably, 1 CpG site (PRDM16_1) near the TSS of PRDM16 was hypomethylated in patients highly expressing PRDM16 (Figure 5A). In contrast, the remaining 9 CpG sites (PRDM16_2-10) located in the PRDM16 gene body were hypermethylated and colocalized at polycomb repressive complex target regions (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figure 6). Furthermore, 6 of these 9 sites were present in the 567 CpG sites that were identified as abnormal DNA methylation sites associated with OS (Figure 1). The ATAC-seq of 5 AMLs (supplemental Table 2) revealed that chromatin accessibility was enhanced only in 2 AMLs with high PRDM16 expression at the TSS region of PRDM16 (Figure 5C), TSS of SCHIP1 (Figure 5D), and 22 other CpG sites (supplemental Figure 7), which were hypomethylated among the 244 CpG sites in patients with high PRDM16 expression (Figure 5A). These opened regions occurred not only in TSSs but also in the gene body and intergenic regions (supplemental Table 7). These results revealed that molecular feature–specific hypomethylation could be a marker of enhanced chromatin accessibility in pediatric AML.

Strong associations of DNA methylation profiles with PRDM16 expression. (A) Heatmap of the DNA methylation profiles based on the methylation values of 244 CpG sites associated with PRDM16 expression. Arrangement of the 64 patients according to a series of PRDM16 expression values (more rightward column location indicates stronger PRDM16 expression) yielded 2 groups with distinct methylation patterns. This classification substantially distinguished patients with high and low PRDM16 expression. (B) Heatmap of 30 CpG sites associated with particularly large differences in methylation values between patients with high and low PRDM16 expressions. (C) Chromatin state annotations for the PRDM16 gene across 127 reference epigenomes based on the National Institutes of Health Roadmap project and chromatin accessibility of the PRDM16 gene in 5 patients with pediatric AML. Chromatin status is indicated by color information, such as purple for bivalent chromatin and gray for repressed polycomb. Supplemental Figure 9 provides details. Only 10 CpG sites among the 649 array probes corresponding to PRDM16 exhibited significant differences in methylation according to PRDM16 expression levels. (D) TSSs of SCHIP1 in which 4 CpG sites were included in the 244 CpG sites opened specifically in the 2 AMLs with high PRDM16 expression.

Strong associations of DNA methylation profiles with PRDM16 expression. (A) Heatmap of the DNA methylation profiles based on the methylation values of 244 CpG sites associated with PRDM16 expression. Arrangement of the 64 patients according to a series of PRDM16 expression values (more rightward column location indicates stronger PRDM16 expression) yielded 2 groups with distinct methylation patterns. This classification substantially distinguished patients with high and low PRDM16 expression. (B) Heatmap of 30 CpG sites associated with particularly large differences in methylation values between patients with high and low PRDM16 expressions. (C) Chromatin state annotations for the PRDM16 gene across 127 reference epigenomes based on the National Institutes of Health Roadmap project and chromatin accessibility of the PRDM16 gene in 5 patients with pediatric AML. Chromatin status is indicated by color information, such as purple for bivalent chromatin and gray for repressed polycomb. Supplemental Figure 9 provides details. Only 10 CpG sites among the 649 array probes corresponding to PRDM16 exhibited significant differences in methylation according to PRDM16 expression levels. (D) TSSs of SCHIP1 in which 4 CpG sites were included in the 244 CpG sites opened specifically in the 2 AMLs with high PRDM16 expression.

Association of DNA methylation regulation and TFs

Because we identified 17 AMLs in which methylation levels were clearly dissociated from others according to PRDM16 expression levels (Figure 5A), we focused on the methylation levels of these 17 AMLs. Between the 17 AMLs of high PRDM16 expression and those of low PRDM16 expression, 4849 CpG sites were significantly different. The TF-binding motifs were significantly enriched only at 1893 hypomethylated CpG sites (supplemental Figure 8A); among the 15 significant TF motifs, the AP-1 motif was enriched (supplemental Figure 8B). Meanwhile, the STAT5 motif was not included in the 15 significant motifs.

We confirmed that the 2 AMLs with high PRDM16 expression analyzed by ATAC-seq specifically enhanced chromatin accessibility at the AP-1 motif for which methylation levels were significantly altered in the nearby 17 AMLs of high PRDM16 expression; these sites were reported to be distal enhancer-like signatures (supplemental Figure 8C).32 Further analysis revealed that 8 AMLs with FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 expression in cluster A, shown in Figure 3A, significantly regulated methylation at 7629 CpG sites, ≥20% more than those in cluster C. Again, TF-binding motifs were significantly enriched only in the hypomethylated 3180 CpG sites (supplemental Figure 9A). Among them, both AP-1 and STAT5 motifs were included (supplemental Figure 9B). Clustering by STAT5- or AP-1–binding CpG sites classified AMLs with FLT3-ITD and high PRDM16 expression not only in our cohort but also in the TARGET cohort (supplemental Figure 10). These results suggest that AMLs in which FLT3-ITD and PRDM16 expression were high concurrently occurred with aberrant AP-1 and STAT5 signaling. However, these 2 signals did not seem to directly explain why FLT3-ITD induced extraordinal expression of PRDM16 or vice versa. Neither of the TFs has been reported to bind the promoter of PRDM16 by ENCODE reference data.33

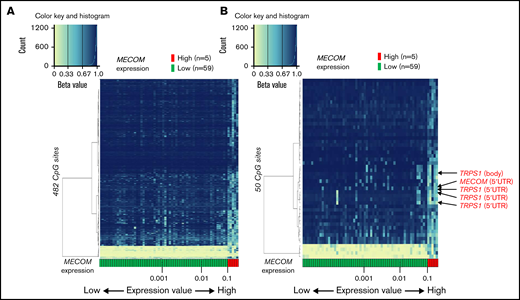

Cutoff values of MECOM expression as defined by DNA methylation analysis

We extracted 482 CpG sites that were significantly associated with MECOM expression and investigated the relationship between expression of this gene and DNA methylation profiles. The arrangement of 64 patients according to a series of MECOM expression values yielded 2 groups with distinct DNA methylation patterns (Figure 6A). Similar to PRDM16, the methylation pattern was drastically changed at this border (MECOM/ABL1 = 0.10). hierarchical clustering of methylation values of the 50 CpG sites with the smallest P values revealed that high MECOM expression was significantly associated with hypomethylation at 4 CpG sites in transcriptional repressor GATA-binding 1 (TRPS1), which encodes a member of the GATA family of transcriptional repressors (Figure 6B).34 These results imply that the PRDM16 and MECOM expression cutoff points3 with PRDM16/ABL1 ratio ≥0.10 and MECOM/ABL1 ratio ≥0.10 were associated with signature DNA methylation patterns. Moreover, specific CpG sites within the gene bodies of PRDM16 were significant markers indicative of a high PRDM16 expression.

Association of DNA methylation profiles with MECOM expression. (A) Heatmap of DNA methylation profiles according to the methylation values at the 482 CpG sites associated with MECOM expression. Arrangement of 64 patients according to a series of MECOM expression values (more rightward column location indicates stronger PRDM16 expression) yielded 2 groups with distinct methylation patterns. This classification substantially distinguished patients with high and low MECOM expression (left). (B) Heatmap of 50 CpG sites associated with particularly large differences in methylation values between patients with high and low MECOM expressions (right).

Association of DNA methylation profiles with MECOM expression. (A) Heatmap of DNA methylation profiles according to the methylation values at the 482 CpG sites associated with MECOM expression. Arrangement of 64 patients according to a series of MECOM expression values (more rightward column location indicates stronger PRDM16 expression) yielded 2 groups with distinct methylation patterns. This classification substantially distinguished patients with high and low MECOM expression (left). (B) Heatmap of 50 CpG sites associated with particularly large differences in methylation values between patients with high and low MECOM expressions (right).

Discussion

In this study, we examined genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in 64 pediatric patients with de novo AML. The unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the patients’ DNA methylation status yielded 4 clusters, which correlated strongly with genetic alterations that are known to indicate AML prognosis. We observed that the hypermethylation and hypomethylation of the 567 extracted CpG sites tended to be associated with worse and better prognosis, respectively. Intriguingly, the methylation pattern of patients with AML with KMT2A-MLLT3 and low MECOM expression resembled that of those harboring RUNX1-RUNX1T1. These findings suggest that the DNA methylation patterns may be also significant prognostic factors in pediatric AML harboring KMT2A-MLLT3 and could potentially elucidate the pathologic mechanisms of AML.

A previous report suggested that the established adverse effect of FLT3-ITD on survival was modulated by a cooccurring variant, such as a WT1 or NPM1 mutation or NUP98-NSD1 fusion.35 Patients with FLT3-ITD harboring a WT1 mutation or NUP98-NSD1 fusion have an adverse prognosis, whereas those with an NPM1 mutation have a favorable prognosis. A similar trend was observed in the present study (Figure 3A; Table 1). Although the number of patients was limited, the DNA methylation pattern distinguished between patients with FLT3-ITD who harbored a WT1 mutation or NUP98-NSD1 fusion versus those who harbored an NPM1 mutation. As described previously,35 patients who harbored a WT1 mutation exhibited aberrant promoter DNA hypermethylation and consequent widespread gene silencing. The prognosis of patients with FLT3-ITD who did not harbor these cooccurring variants could also be distinguished clearly by the DNA methylation patterns (Figure 3A). Accordingly, DNA methylation patterns might be an accurate prognostic factor for patients with FLT3-ITD.

Three TFs were extracted from the TF-binding site analysis for the 1243 regions in which significantly different DNA methylations were confirmed, with the lowest P value between AMLs with and without FLT3-ITD (Figure 4A). Of these, STAT5 has been reported to be an effector activated by FLT3-ITD, thus leading to cell proliferation and antiapoptosis.36 Furthermore, FLT3-ITD has been reported to be linked to a distinct DNA methylation signature targeting STAT sites.37 Next, we investigated CpG sites that showed significantly different methylation statuses between PRDM16_high (red) and PRDM16_low (green) AMLs, shown in Figure 5A. The STAT5-binding sites do not seem to correlate with high expression of PRDM16 (supplemental Figure 8A-B). Instead, the AP-1–binding motif was involved in high PRDM16 expression. Finally, AMLs harboring FLT3-ITD concomitant with high PRDM16 expression included STAT5- and AP-1–binding motifs in nearby altered DNA methylation CpG sites (supplemental Figure 9). We reconfirmed these results in the TARGET cohort (supplemental Figure 10). Therefore, methylation levels at STAT5- and AP-1–binding sites may correlate with high expression of PRDM16 with FLT3-ITD, synergistically.

We previously identified high levels of PRDM16 expressions as a poor prognostic factor in pediatric AML.3,4 In this study, we revealed that highly expressed PRDM16 in AML exhibited significant hypermethylation within the PRDM16 gene body at 9 CpG sites with polycomb repressive complex target regions (Figure 5C). It was only these 9 that methylation was significantly changed within 614 array probes of PRDM16 genes. These results indicated that significant methylation changes at the 9 CpG sites were markers for estimating the degree to which PRDM16 expression levels were related to AML methylome aberrance. PRDM16 is highly homologous to MDS1/EVI1, which is an alternatively spliced transcript of MECOM,38 and both PRDM16 and MECOM encode histone H3 lysine 9 monomethyltransferases, which maintain heterochromatin integrity.39 Recent reports have demonstrated the distinct roles for Prdm16 isoforms.40,41 We revealed that methylation at the 4 CpG sites near the alternative TSS of SCHIP1 (ENST00000482804.1) clearly decreased in AMLs with highly expressed PRDM16 concomitantly with enhanced chromatin accessibility and increased transcript levels. Two of the 4 CpG sites at SCHIP1 were included in the 1243 CpG sites that were differentially methylated, with >20% between FLT3-ITD+ and FLT3-ITD−. It is impossible to discriminate between the effects of FLT3-ITD and PRDM16 high expression on the changes in DNA methylation in our study. SCHIP1 encodes a cytoskeletal protein and is identified as an intermediate early gene controlled by PDGF signaling.42,43 PDGF receptors and FLT3 are both type 3 receptor tyrosine kinases. Gene rearrangements of PDGFRA and PDGFRB have been reported in AML.44,45 Additional molecular aberrations or cross talk between PDGFR and FLT3 might be involved in DNA methylation changes.

In summary, we successfully classified pediatric AML in accordance with characteristics of molecular biology by studying the DNA methylation levels of extracted CpG sites. Furthermore, from the methylation differences between AML with FLT3-ITD with and without high expression of PRDM16, we identified TF-binding sites of STAT5 and AP-1, which may be specifically involved in aberrant cell signaling. Targeting molecules for cytogenetically specific AML may facilitate the decision of which drugs to administer. Finally, we confirmed that the methylation pattern drastically changed between high and low PRDM16 expression. The results of ATAC-seq supported that hypomethylation was associated with high chromatin accessibility and corresponding gene expression, especially of HOXB genes, SCHIP1, and PRDM16. Our findings suggest that DNA methylation plays a key role in leukemogenesis and serves as a useful novel biomarker of pediatric AML.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the ENCODE Consortium and the ENCODE production laboratories, Bradley Bernstein laboratory (Broad Institute), Richard Myers laboratory (HudsonAlpha Institute for Biology), Vishwanath Iyer laboratory (University of Texas at Austin), John Stamatoyannopoulos laboratory (University of Washington), and Michael Snyder laboratory (Stanford University). The authors also thank Enago for English language review.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and Exploratory Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (16K20951 [N.S.] and 20K17414 [G.Y.]) and by the Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED_15ck0106066h0002, JP16ck0106064, JP19ck0106329, and 19ek0109348s0102; Y. Hayashi).

Authorship

Contribution: G.Y., T. Kawai, and N.S. wrote the paper; G.Y., T. Kawai, N.S., J.I., Y. Hara, K.O., S.-I.T., T. Kaburagi, and K.Y. performed the experiments; G.Y., T. Kawai, N.S., M.S., H.A., S.O., and K. Hata analyzed the data and results; N.K., D.T., A.S., S.A., T.T., and K. Horibe collected the data and samples; Y.S. and S.M. developed the bioinformatic tools; Y. Hayashi designed the study and supervised the work; and all authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yasuhide Hayashi, Institute of Physiology and Medicine, Jobu University, 270-1 Shinmachi, Takasaki, 370-1393 Gunma, Japan; e-mail: hayashiy@jobu.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

G.Y. and T. Kawai contributed equally to this study.

DNA methylation data are available at National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus under accession #GSE133986 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE133986).

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to Yasuhide Hayashi (hayashiy@jobu.ac.jp).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.