Abstract

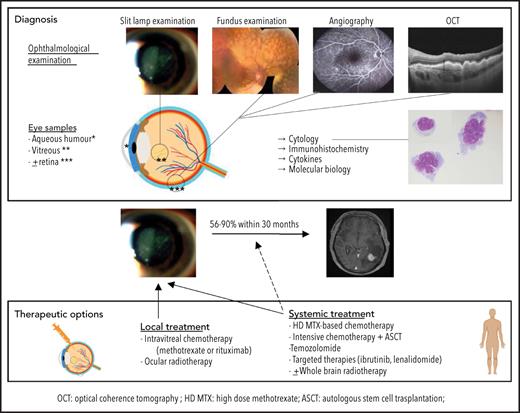

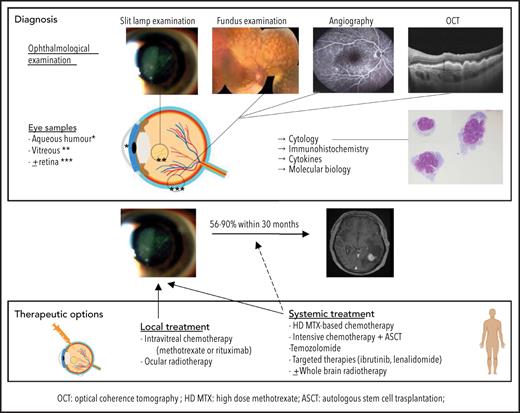

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) is a rare form of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (PCNSL) arising in the intraocular compartment without brain involvement. Despite its apparent indolent clinical course, PVRL can cause permanent vision loss and CNS relapse, the major cause of death in patients with PVRL. The pathophysiology of PVRL is unknown. As in PCNSL, the transformation of the tumor cells likely originates outside the CNS, before the cells migrate to the eye and proliferate within an immune-permissive microenvironment. PVRL exhibits a biased immunoglobulin repertoire, suggesting underlying antigen selection. The diagnosis remains challenging, requiring close coordination between ophthalmologists and cytologists. Because of their rarity and fragility in the vitreous, lymphoma cells cannot always be identified. Interleukin levels, molecular biology, and imaging are used in combination with clinical ophthalmological examination to support the diagnosis of PVRL. Multi-institutional prospective studies are urgently needed to validate the equivocal conclusions regarding treatments drawn from heterogeneous retrospective or small cohort studies. Intravitreal injection of methotrexate or rituximab or local radiotherapy is effective at clearing tumor cells within the eyes but does not prevent CNS relapse. Systemic treatment based on high-dose methotrexate chemotherapy, with or without local treatment, might reduce this risk. At relapse, intensive consolidation chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation can be considered. Single-agent ibrutinib, lenalidomide, and temozolomide treatments are effective in patients with relapsed PVRL and should be tested as first-line treatments. Therapeutic response assessment based on clinical examination is improved by measuring cytokine levels but still needs to be refined.

Introduction

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) arises in the intraocular compartment without brain involvement, constituting a rare subgroup of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (PCNSL).1 Because of clinical similarities to uveitis and initial response to steroid therapy, the PVRL diagnosis may be delayed. The initial indolent clinical course must not be seen to minimize the severity of this disease, which can result in permanent vision loss or CNS relapse with a poor prognosis. Therapeutic options range from local ocular treatment to systemic therapy based on high-dose (HD) methotrexate (MTX) and even intensive chemotherapy (IC) with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). The diagnostic procedure is improved by analyses of biomarkers and molecular biological parameters. Efforts are needed to better assess the therapeutic response.

This review aims to summarize the most important studies in the field of PVRL, including their pitfalls and limitations, to assist with decision making in clinical practice and better identify the next challenges to address in this disease.

Definition and epidemiology

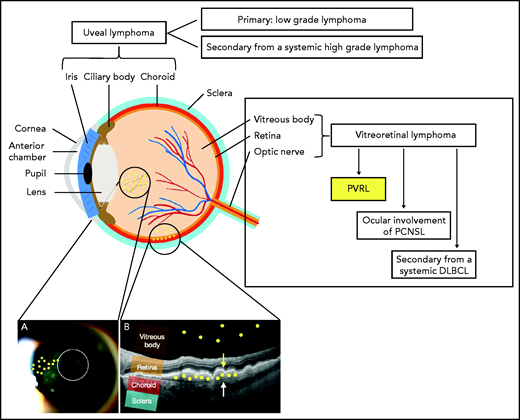

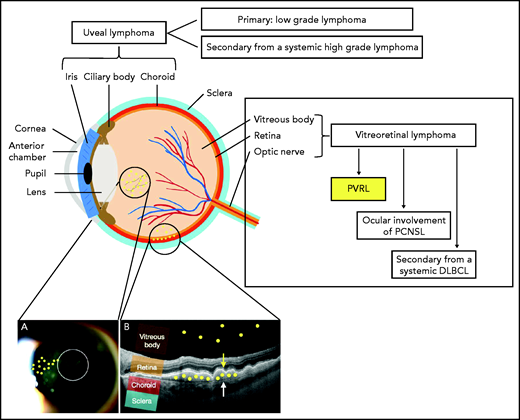

PVRL is a rare high-grade extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma affecting the vitreous, retina, or in rare cases the optic nerve in the absence of brain parenchyma infiltration. It must be distinguished from secondary vitreoretinal or choroidal invasion by systemic lymphoma and from primary uveal lymphoma, which arises in the choroid, iris, or ciliary body, and is mainly a type of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (Figure 1).2 The vitreoretinal involvement present at the diagnosis of PCNSL, which occurs in 15% of patients with PCNSL,3 falls outside the definition of PVRL.

Schema of the anatomy of the eye and anatomical classification of intraocular lymphoma (IOL). IOL can occur in the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body, and choroid) as a primary (mainly mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma) or secondary (to systemic lymphoma) form. IOL that occurs in the vitreous body, the retina, or in rare cases the optic nerve is called vitreoretinal lymphoma (VRL). VRL is subdivided into PVRL, ocular involvement of PCNSL, and secondary lymphoma from systemic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The typical localization of lymphoma cells in the case of PVRL is represented by the small yellow circles drawn on the picture. (A) Slit-lamp examination of an eye affected by PVRL showing the infiltration of lymphoma cells in the anterior vitreous and along the vitreous fibrils. (B) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of the retina illustrating the infiltration of lymphoma cells into the subretinal space between the retinal pigmented epithelium (yellow arrow) and the Bruch membrane (white arrow) or into the vitreous body.

Schema of the anatomy of the eye and anatomical classification of intraocular lymphoma (IOL). IOL can occur in the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body, and choroid) as a primary (mainly mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma) or secondary (to systemic lymphoma) form. IOL that occurs in the vitreous body, the retina, or in rare cases the optic nerve is called vitreoretinal lymphoma (VRL). VRL is subdivided into PVRL, ocular involvement of PCNSL, and secondary lymphoma from systemic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The typical localization of lymphoma cells in the case of PVRL is represented by the small yellow circles drawn on the picture. (A) Slit-lamp examination of an eye affected by PVRL showing the infiltration of lymphoma cells in the anterior vitreous and along the vitreous fibrils. (B) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of the retina illustrating the infiltration of lymphoma cells into the subretinal space between the retinal pigmented epithelium (yellow arrow) and the Bruch membrane (white arrow) or into the vitreous body.

A majority of PVRL cases are a form of high-grade DLBCL.4 Like PCNSL, PVRL may be said to belong to the activated-B cell type (ABC) of lymphoma,5 more specifically to the subgroup of ABC DLBCL, with frequent mutations in CD79 and MYD88L265P and a less favorable outcome than other ABC subgroups.6,7 Rare cases of unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and T-cell lymphoma are encountered.

True epidemiological data are lacking. PVRL incidence is estimated to be 50 cases per year in the United States.4 PVRL represents ∼5% of the patients registered in the French database for oculocerebral lymphomas and accounts for 10 new cases per year.3,8 PVRL usually occurs in immunocompetent adults in their 50s, with a slight female predominance but no racial predilection.4,9 Some cases have been described in patients with immunosuppression, usually associated with Epstein-Barr virus.10 PVRL is mainly bilateral, although asymmetrical presentations are encountered.

Pathophysiology of PVRL and CNS relapse

PVRL pathophysiology remains to be deciphered. The lymphoma cell origin is unknown, but similarly to PCNSL, the transformation of the tumor cells likely originates outside the CNS, before the cells migrate to the eye and proliferate. The microenvironments of the CNS and the eyes share similar characteristics. The retina is isolated from the vascular and perivascular compartments by 2 blood-retinal barriers (BRBs), composed of cells linked by tight junctions at the level of the intraretinal capillary endothelial cells (inner BRB) and the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE; outer BRB), which substantially restrict paracellular diffusion of molecules into the retina from the vascular and perivascular compartments, respectively.11 The ocular microenvironment shows low expression of major histocompatibility complex class molecules and is enriched in immunosuppressive molecules, such as transforming growth factor β, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, and Fas ligands, which suppress the activation of T helper 1 (Th1) cells and the inflammatory activity of macrophages and prevent natural killer cell activation. The secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10), an immunosuppressive cytokine, by lymphoma cells may increase immune tolerance and allow tumor cells to escape the immune system.12,13 Data on ocular immune reactions to tumor cells are scarce. Impaired Th1 cytokine production by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes has been documented in PVRL animal models.13

According to a recent study,14 PVRL displayed very high levels of immunoglobulin gene mutations, especially in the IGHV4-34 sequences and in a significantly higher proportion than in PCNSL. This biased immunoglobulin repertoire suggests that antigen selection plays a major role in PVRL development and highlights a potential role for inhibitors of the B-cell receptor signaling pathway in blocking the activity of the NF-κB pathway, which is activated in ABC DLBCL.15 The galectin-3 protein, which is recognized by antibodies using the IGHV4-34 gene and is expressed in cells from both the brain microenvironment and the RPE, is a candidate antigen.14,16 Additional studies are needed to identify the antigen responsible for PVRL.

The pathophysiology of CNS relapse from PVRL is poorly documented. Whether CNS relapse results from subclinical brain disease involvement that is not detectable with routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at diagnosis or from dissemination from the eye through the retina and optic nerve is still a matter of debate. Experiments using murine models17,18 support the hypothesis of dissemination through the RPE into the choroid, thus highlighting the importance of achieving complete remission (CR) in the eye. The detection of IL-10 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with PVRL, without CSF or brain involvement of lymphoma,19 might suggest subclinical brain involvement of the disease.19

Diagnosis

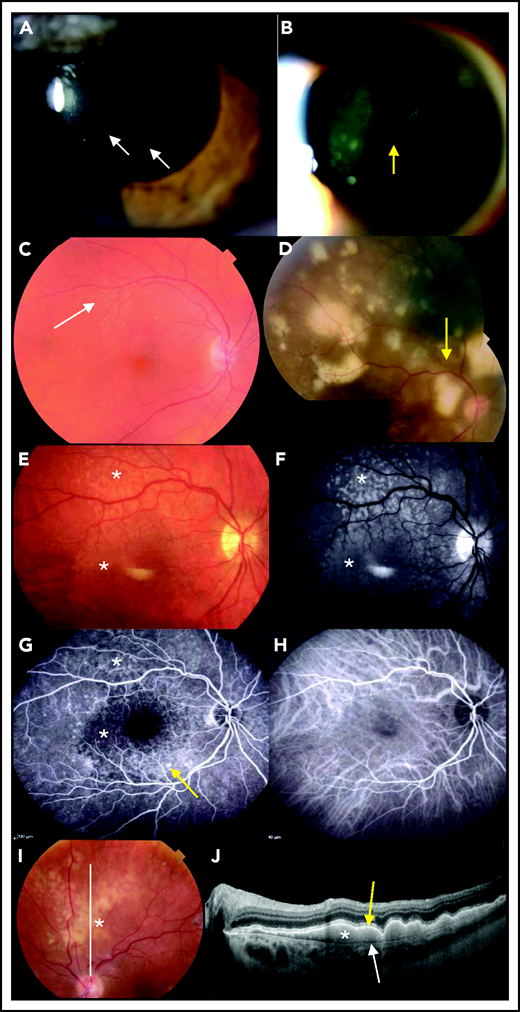

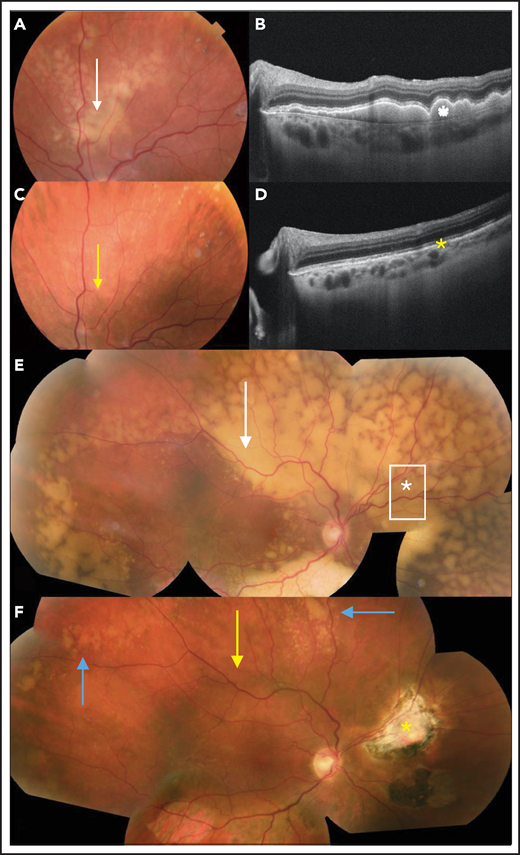

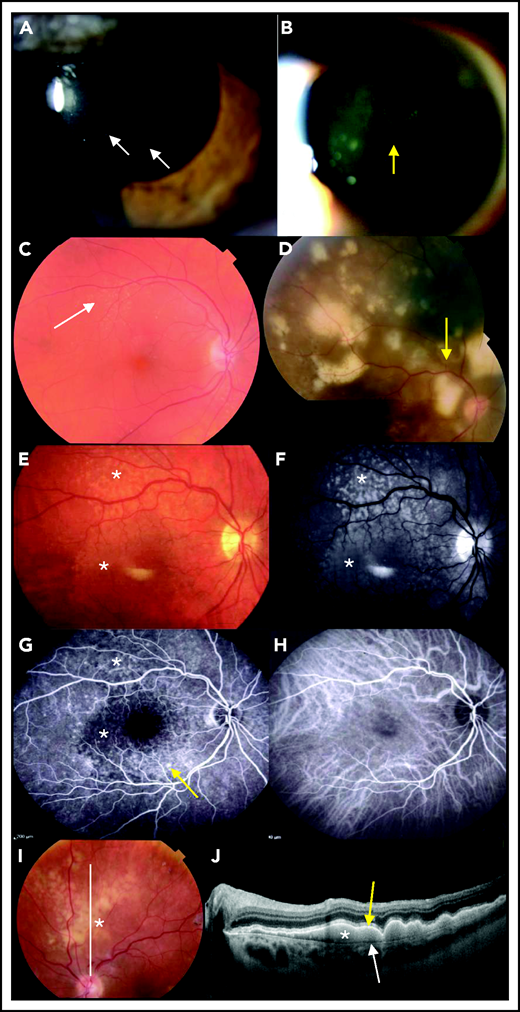

Distinguishing PVRL from posterior uveitis is still a challenge for ophthalmologists. PVRL is part of the well-named masquerade syndrome: insidious onset, initial response to steroids, and delayed diagnosis resulting in part from the common prolonged and indiscriminate use of steroids are common.4 The median time from first symptoms to diagnosis ranges from 6 to 40 months,9,20,21 compared with 35 days for PCNSL.22 Patients may complain of floaters or blurred vision.4 A slit-lamp examination reveals a quiet anterior chamber with no protein flare and some cellular gray diffuse keratic precipitates. Lymphoma cell clumps are noticeable in the anterior vitreous or along the vitreous fibrils. Lymphoma cells may also infiltrate the retina (multifocal cream-colored retinal spots on funduscopic imaging) or grow along the Bruch membrane under the RPE. Multimodal retinal imaging reveals the typical but nonpathognomonic leopard skin pattern, while subretinal cell deposits are highlighted with noninvasive OCT (Figure 2). Clinical findings and paraclinical signs of PVRL and uveitis are summarized in Table 1.

Ophthalmological findings and multimodal imaging of PVRL. (A) Slit-lamp examination showing a quiet anterior chamber with no protein flare and some cellular gray diffuse keratic precipitates (white arrows). (B) A clump of lymphoma cells is visible in the slit-lamp examination in the anterior vitreous or along the vitreous fibrils (yellow arrow). (C) At diagnosis, a fundus examination reveals only subtle small yellowish retinal lesions (white arrow). (D) The (sub)retinal lesions detected at diagnosis are more extended and multifocal (yellow arrow; composite color fundus photograph, with photos merged together with built-in camera software) (E) Retinal photograph showing cream-colored subretinal deposits (white asterisks). (F) Infrared photograph of the same patient shown in panel E, showing hyperreflective lesions corresponding to the lesions visible in panel E (white asterisks). (G) Fluorescein angiography of the same patient shown in panel E, showing the lymphoid infiltration as dark spots masking the underlying fluorescence of the choroid (white asterisks). RPE alterations appear as hyperfluorescent areas because of window effects (yellow arrow). (H) Indocyanine angiography of the same patient shown in panel E, with poorly contributive hypocyanescent lesions visualized. (I) Fundus photograph showing patchy yellowish subretinal lesions (white asterisk). (J) OCT image of the retina along the white line in panel I showing subretinal hyperreflective deposits of lymphoma cells (white asterisk) that are located between the RPE (yellow arrow) and the Bruch membrane (white arrow).

Ophthalmological findings and multimodal imaging of PVRL. (A) Slit-lamp examination showing a quiet anterior chamber with no protein flare and some cellular gray diffuse keratic precipitates (white arrows). (B) A clump of lymphoma cells is visible in the slit-lamp examination in the anterior vitreous or along the vitreous fibrils (yellow arrow). (C) At diagnosis, a fundus examination reveals only subtle small yellowish retinal lesions (white arrow). (D) The (sub)retinal lesions detected at diagnosis are more extended and multifocal (yellow arrow; composite color fundus photograph, with photos merged together with built-in camera software) (E) Retinal photograph showing cream-colored subretinal deposits (white asterisks). (F) Infrared photograph of the same patient shown in panel E, showing hyperreflective lesions corresponding to the lesions visible in panel E (white asterisks). (G) Fluorescein angiography of the same patient shown in panel E, showing the lymphoid infiltration as dark spots masking the underlying fluorescence of the choroid (white asterisks). RPE alterations appear as hyperfluorescent areas because of window effects (yellow arrow). (H) Indocyanine angiography of the same patient shown in panel E, with poorly contributive hypocyanescent lesions visualized. (I) Fundus photograph showing patchy yellowish subretinal lesions (white asterisk). (J) OCT image of the retina along the white line in panel I showing subretinal hyperreflective deposits of lymphoma cells (white asterisk) that are located between the RPE (yellow arrow) and the Bruch membrane (white arrow).

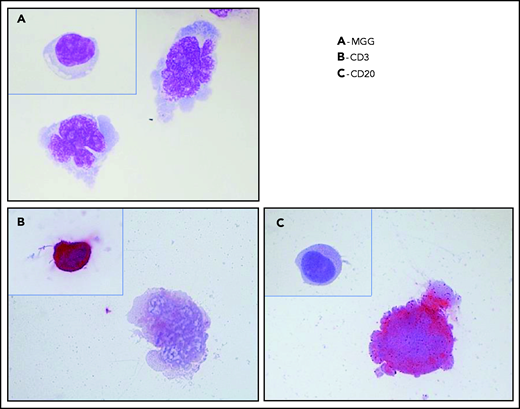

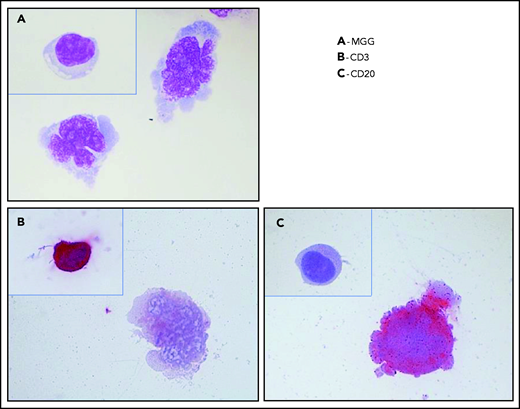

Although an ophthalmic examination and ocular imaging might raise clinical suspicion,23 the gold standard for PVRL diagnosis is still the cytological identification of lymphomatous cells in the eye (Figure 3). A diagnostic vitrectomy is usually performed. Less frequently, a retinal biopsy is necessary. A cytological examination, immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, measurement of cytokine levels, and molecular examinations of these samples should be combined to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the PVRL diagnosis.10 The diagnosis could remain challenging because of a limited sample volume, low cellularity of vitreous fluid samples, and the extreme fragility of lymphoma cells in the vitreous. The procedures for vitreous sampling and analysis have been described previously24-27 (Table 2). We must emphasize that for a successful diagnostic procedure, the discontinuation of steroids several weeks before vitrectomy, good communication and collaboration between the ophthalmologist and the cytologist/pathologist trained in handling vitreous samples, and an immediate analysis of both pure and diluted vitreous samples preferentially without a fixative are critical.

Typical cytology of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Reconstruction from 4 fields of the same cytospin (magnification x100 m) (A) May-Grünwald-Giemsa (MGG) staining of a diluted vitrectomy specimen. Cytospin shows 2 large lymphoid cells with basophilic cytoplasm and irregular nuclei, with several nucleoli corresponding to large lymphomatous cells. A small reactive lymphocyte (inset) was visible on another field of the same cytospin. (B) Immunochemistry with an anti-CD3 antibody and alkaline phosphatase–antialkaline phosphatase (APAAP) staining showing the negativity of a large lymphoma cell and the positivity of a reactive lymphocyte (inset). These 2 cells were identified in 2 different fields on the same cytospin. (C) Immunochemistry with an anti-CD20 antibody and APAAP staining showing the positivity of a large lymphoma cell and the negativity of a reactive lymphocyte (inset). These 2 cells were identified in 2 different fields on the same cytospin.

Typical cytology of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Reconstruction from 4 fields of the same cytospin (magnification x100 m) (A) May-Grünwald-Giemsa (MGG) staining of a diluted vitrectomy specimen. Cytospin shows 2 large lymphoid cells with basophilic cytoplasm and irregular nuclei, with several nucleoli corresponding to large lymphomatous cells. A small reactive lymphocyte (inset) was visible on another field of the same cytospin. (B) Immunochemistry with an anti-CD3 antibody and alkaline phosphatase–antialkaline phosphatase (APAAP) staining showing the negativity of a large lymphoma cell and the positivity of a reactive lymphocyte (inset). These 2 cells were identified in 2 different fields on the same cytospin. (C) Immunochemistry with an anti-CD20 antibody and APAAP staining showing the positivity of a large lymphoma cell and the negativity of a reactive lymphocyte (inset). These 2 cells were identified in 2 different fields on the same cytospin.

Cytology provides morphological evidence of PVRL. Because of the difficulties of sampling, the sensitivity of cytology alone in diagnosing PVRL is low (45% to 60%).28 Immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry of pan B-cell markers can show a CD20+ population of B cells with monotypical light chain expression.29,30 Monoclonality can be identified by polymerase chain reaction to detect immunoglobulin heavy-chain or κ light-chain gene rearrangement.31-33 Results of flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction analyses must be interpreted with caution in samples with low cellularity.

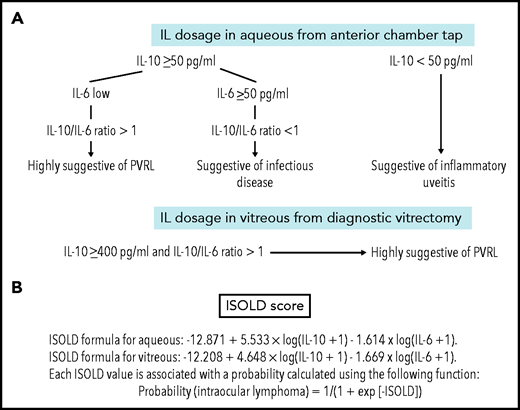

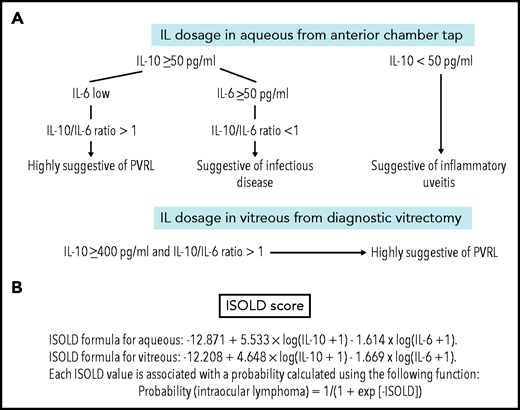

IL-10 measurements in pure vitreous or aqueous samples are a significant diagnostic aid when PVRL is clinically suspected. High IL-10 levels in the vitreous or anterior chamber favor a diagnosis of PVRL, whereas high IL-6 levels are more specific to inflammatory or infectious diseases. The IL-10/IL-6 ratio is thus very helpful in determining the PVRL diagnosis34-36 while avoiding errors related to sample dilution. Caution remains for pure retinal localization, which may not be accompanied by an increase in IL-10 in intraocular fluids. Cassoux et al12 defined specific IL-10 cutoffs of 50 pg/mL in the aqueous humor (sensitivity, 89%; specificity, 93%) and 400 pg/mL in the vitreous (sensitivity, 80%; specificity, 99%; Figure 4). More recently, the Interleukin Score for Intraocular Lymphoma Diagnosis, which combines the IL-10 and IL-6 levels, was proposed as a probability score for the diagnosis of PVRL (Figure 4).37 Assessments of interleukin levels are currently routine procedures for the screening and follow-up of PVRL in many referral centers, because an anterior chamber tap is a rapid and minimally invasive procedure.38

Interleukin levels in case of clinical suspicion of PVRL. (A) IL-10 and IL-6 levels in the aqueous humor and vitreous for PVRL screening and diagnosis. In the aqueous humor, an absolute level of IL-10 ≥50 pg/mL and IL-10/IL-6 ratio >1 is suggestive of PVRL (IL-10 cutoff: sensitivity, 89%; specificity, 93%). In patients with uveitis, the level of IL-10 is low and IL-10/IL-6 ratio is <1. In patients with an infectious disease, the IL-10 level might exceed 50 pg/mL, but the IL-6 level might also be >50 pg/mL; the IL-10/IL-6 ratio is <1. In the vitreous, the absolute level of IL-10 ≥400 pg/mL and IL-10/IL-6 ratio >1 are also suggestive of PVRL (IL-10 cutoff: sensitivity, 80%; specificity, 99%). Data adapted.12,100 (B) The Interleukin Score for Intraocular Lymphoma Diagnosis (ISOLD) is a probability score for the diagnosis of PVRL based on a mathematical formula combining both IL-10 and IL-6 levels in vitreous or aqueous samples with high sensitivity and specificity (93% and 95%, respectively). Data adapted.37

Interleukin levels in case of clinical suspicion of PVRL. (A) IL-10 and IL-6 levels in the aqueous humor and vitreous for PVRL screening and diagnosis. In the aqueous humor, an absolute level of IL-10 ≥50 pg/mL and IL-10/IL-6 ratio >1 is suggestive of PVRL (IL-10 cutoff: sensitivity, 89%; specificity, 93%). In patients with uveitis, the level of IL-10 is low and IL-10/IL-6 ratio is <1. In patients with an infectious disease, the IL-10 level might exceed 50 pg/mL, but the IL-6 level might also be >50 pg/mL; the IL-10/IL-6 ratio is <1. In the vitreous, the absolute level of IL-10 ≥400 pg/mL and IL-10/IL-6 ratio >1 are also suggestive of PVRL (IL-10 cutoff: sensitivity, 80%; specificity, 99%). Data adapted.12,100 (B) The Interleukin Score for Intraocular Lymphoma Diagnosis (ISOLD) is a probability score for the diagnosis of PVRL based on a mathematical formula combining both IL-10 and IL-6 levels in vitreous or aqueous samples with high sensitivity and specificity (93% and 95%, respectively). Data adapted.37

MYD88 and CD79B gene mutations are frequently reported in PCNSL.7 The most common mutation, MYD88L265P, increases NF-κB activity, which promotes cell survival.39 The MYD88L265P mutation was observed in the vitreous in up to 88% of a series of 25 patients with PVRL.40 Adding the MYD88 gene mutation test might improve the diagnostic yield of vitreous fluid.41 Concomitant MYD88 mutations were detected in paired aqueous and vitreous samples from a small series of patients.42,43

CD79B, which encodes the B-cell receptor, was mutated in 35% of a series of 17 patients with PVRL.44 Yonese et al44 suggested an association between the CD79B mutation and a poorer prognosis because of earlier CNS involvement.

Recent epigenetic studies identified microRNAs such as miR-6513-3p and miR-1236-3p in the vitreous and serum that might serve as candidate PVRL biomarkers.45,46 Whole-exome sequencing to determine the PVRL mutation profile was recently conducted, but small targeted gene panel tests remain to be developed.47

In summary, a definite PVRL diagnosis relies on the cytological identification of malignant lymphoid cells with monotypic and/or clonal characteristics. This diagnosis may be challenging when cytological evidence of PVRL is lacking because of a low-cellularity or poor-quality sample. In these cases, the PVRL diagnosis will be highly probable based on evidence from multiple tests combining an ophthalmological clinical examination, imaging (such as angiography or OCT), and measurements of IL-10/IL-6 levels for Interleukin Score for Intraocular Lymphoma Diagnosis scoring.

Cerebral MRI, CSF examination including cytology and ideally flow cytometry for lymphoid markers, computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography of the chest/abdomen and pelvis, and bone marrow biopsy are necessary in the initial disease assessment to rule out brain and extraCNS lymphoma involvement.

Therapeutic issues

Therapeutic challenges for PVRL are dual. Local and CNS relapses are frequent. Fifty-six percent to 90% of patients with PVRL ultimately develop CNS dissemination within 30 months.4,9,48

The median progression-free survival (PFS) ranges from 18 to 29 months.8,9 However, overall survival (OS), ranging from 58 to 75 months,8,9 is longer than the estimated survival of patients with PCNSL.22 Therapy aims to treat the intraocular and retinal disease to restore the patient’s vision and decrease the incidence of CNS relapse, which represents the main cause of death.4,48,49

Different treatment strategies are available9,50-57: local treatment, such as intravitreal (IVT) injection of chemotherapy or ocular radiotherapy (ORT); systemic treatment; or a combination of both. Debate persists regarding which strategy to adopt as the first-line treatment. The large number of published studies reflects the efforts of medical teams to improve the prognosis of patients with PVRL. However, many pitfalls hinder their interpretation. The largest retrospective studies involved patients who received multiple treatments, resulting in small subgroups receiving similar treatments. The few prospective studies available were conducted in a very limited number of patients. Interestingly, the median survival seems longer in patients treated at the time of PVRL diagnosis than in patients treated at the time of CNS relapse.58

How patients are monitored for the early detection of an ocular or CNS relapse is usually not specified in the published series. Differences in monitoring procedures may account for part of the observed differences in PFS.

First-line treatment

Local treatment

The goal of local treatment is to induce intraocular CR and improve vision without systemic toxicity. Studies have not proved whether the achievement of local CR reduces the risk of CNS relapse.

The IVT route for chemotherapy is an interesting procedure to rapidly reach intraocular cytotoxic drug concentration. Data on the ocular bioavailability of IVT chemotherapy are scarce. De Smet et al59 showed that a single IVT injection of 400 μg of MTX remained effective for >5 days (Table 3). Kim et al60 determined that the half-life of rituximab in the rabbit vitreous (IVT injection of 1 mg/0.1 mL) is 4.7 days.

IVT injection is a safe procedure performed under topical anesthesia.61 MTX is the main drug used for IVT injection at a dose of 0.4 mg/0.1 mL. Various IVT administration schedules have been published (data supplement).62-65 The induction phase consists of IVT injections twice per week for 4 weeks. The treatment is then followed by a predetermined number of IVT injections (for a total of 25 IVT injections over 1 year) or driven by the clinical response or the IL-10 level in the aqueous humor51,65,66 to decrease the number of IVT injections.

IVT rituximab injections at a dose of 1 mg/0.1 mL, alone or combined with IVT injections of MTX, are an interesting alternative that would require fewer injections to control PVRL. Protocols vary between authors.66-68 Some authors also reported IVT injections of melphalan.69,70

The main IVT MTX–related adverse effects are transient intraocular hypertonia, epithelial keratopathy,63,64 and in some cases drug resistance.71 Reversible uveitis may occur after IVT rituximab.68 These adverse effects are reduced by performing an anterior chamber tap before the IVT injection to reduce intraocular pressure and drug reflux and abundant washing of the cornea with saline. The obtained aqueous sample is then used to monitor the IL-10 level. Intraocular hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and endophthalmitis are rare vision-threatening adverse effects caused by the procedure of IVT injection (occurring in 0.06%, 0.01%, and 0.05% of injections, respectively).72

IVT chemotherapy has been used as first-line treatment, although some authors have used IVT chemotherapy only for ocular relapse or when systemic chemotherapy is contraindicated.4,66,73 The efficacy of IVT chemotherapy as the sole first-line treatment of PVRL cannot be properly assessed because of the heterogeneity encountered in retrospective studies in terms of disease characteristics (eg, initial PVRL or relapse, vitreo-retinal involvement associated with PCNSL) and the frequent association of systemic treatments.

External-beam ORT (30-40 Gy) is an alternative local treatment, although it is rarely offered as the only first-line treatment.4 It is effective for local control of the disease and may be preferable in patients with bilateral disease,4 but it fails to prevent CNS relapse. The risk of cataract and radiation retinopathy decreases with lower doses (<30 Gy) of ORT.9,58,66,74-76

Therapeutic vitrectomy can be considered a palliative treatment to improve vision.77

Systemic and combined (local with or without systemic) treatments

Systemic treatments are empirical and mainly rely on PCNSL-like treatments with HD MTX, based on the anatomical and functional similarities between the blood-brain barrier and the BRB.11 Knowledge of the pharmacokinetics of drugs administered systemically in ocular tissues and fluid is scarce; these have been explored in a few studies of a small number of patients (Table 3). After IV HD MTX and aracytine administration, these drugs were found in the aqueous humor and to a lesser extent in the vitreous shortly after injection.78-80 Ifosfamide and trofosfamide were detectable in the aqueous humor after IV and oral administration, respectively,81 but data regarding the vitreous are lacking for these drugs.

The benefit of combining a first-line treatment with systemic HD MTX chemotherapy and local treatment to decrease the risk of CNS relapse is controversial based on the results of heterogeneous retrospective studies9,50-57,82 (Table 4) that aimed to compare the outcomes of patients who received only local treatment with the outcomes of patients who received systemic treatment or a combination of both. The retrospective study by Hashida et al,55 in which the treatments were more homogeneous, showed significantly delayed CNS relapse in patients who received a combination of local and systemic HD MTX treatments. Because of the aforementioned biases of the published therapeutic studies in patients with PVRL, the failure of retrospective studies to prove the superiority of combined therapeutic approaches should not discourage clinicians from testing treatments with the objective of decreasing CNS relapse. Kaburaki et al57 reported encouraging results from a small prospective series of 11 patients treated with a conventional PCNSL-like treatment consisting of systemic IV rituximab, HD MTX, procarbazine, and vincristine plus reduced-dose whole-brain radiotherapy (23.4 Gy) and IV HD cytarabine combined with IVT MTX. With a median follow-up of 40 months, the estimated 4-year cumulative incidence of CNS progression was only 10%. The combination of bilateral ORT (30-40 Gy) with systemic HD MTX produced encouraging survival results in a cohort of 11 patients but resulted in radiation retinopathy in 9 patients (with optic atrophy [n = 2] or cataract [n = 2]) and bilateral optic nerve atrophy in 1 patient.82

Treatment for R/R PVRL

At relapse, IVT chemotherapy and ORT can be provided as single treatment with the same objectives as those discussed in first-line treatment or to rapidly improve vision in combination with systemic treatment.

IC with or without ASCT

IC plus ASCT has been evaluated in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) PVRL to circumvent the BRB,83-85 mainly with an IC regimen consisting of HD thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide, because this combination of drugs proved feasible and effective in patients with poor-prognosis systemic lymphoma, including in patients with CNS disease involvement,86 and because thiotepa and busulfan have good CNS bioavailability.87 IC plus ASCT proved feasible in patients with R/R PVRL (Table 5). A pilot study reported encouraging results for patients with refractory PVRL after induction chemotherapy based on HD MTX and HD cytarabine83; the 5 patients who received IC plus ASCT achieved CR, and no CNS relapse was observed after ASCT, with a median follow-up of 17 months. Patients with R/R PVRL were included in subsequent retrospective85 and prospective84 studies for R/R PCNSL and PVRL with the same IC plus ASCT regimen. These studies confirmed the efficacy of this therapeutic procedure in patients with R/R PCNSL and PVRL, with no significantly different outcomes between patients with PVRL and PCNSL. Other retrospective studies52 also suggested a beneficial effect of IC plus ASCT in PVRL. Although these statements are based on a small series of patients with PVRL, because of the rarity of this disease, and in the absence of any comparative studies, IC plus ASCT can still be considered a treatment option for relapsed PVRL in younger patients with no severe comorbidities.

Single agents and targeted therapies

Single-agent temozolomide produced encouraging results in a retrospective study involving 21 patients (relapse, n = 19; first line, n = 2).88 The overall response rate was 81%, with 71% achieving CR. The toxicity profile was good. With a median follow-up of 42 months, the median PFS was 12 months, and 5 CNS relapses occurred.

Two targeted therapies, lenalidomide (as a single agent or combined with rituximab) and ibrutinib, showed clinical activity in the ocular compartment in phase 1 and prospective proof-of-concept phase 2 studies89-92 (Table 5). These therapies were tested because of their known efficacy against systemic DLBCL, with preferential antilymphoma activity against the ABC DLBCL subtype.5,14,93,94

In the REVRI study,89 the induction treatment consisted of 8 28-day cycles of rituximab at 375/m2 IV on day 1 and lenalidomide at 20 mg per day on days 1 to 21 for cycle 1 and 25 mg per day on days 1 to 21 for the subsequent cycles. Fifty patients were recruited to the study, including 17 with intraocular disease involvement (11 patients with R/R PVRL and 6 patients with disease involvement of the brain and eyes). In this patient subgroup, the CR rate was 35%. The median PFS of patients with PVRL was 9.2 months. The median OS of patients with PVRL was not reached and was significantly longer than that of patients with PCNSL (P = .03). Although the precise roles of rituximab and lenalidomide in determining the therapeutic outcomes in this population cannot be defined, this study documented the clinical activity of the combination of rituximab and lenalidomide in the ocular compartment.

The prospective multicenter phase 2 iLOC study90 evaluated the activity of ibrutinib as a single agent (560 mg per day every day) in patients with R/R PCNSL and PVRL. Fourteen patients with R/R PVRL were included. After 2 months of treatment, an overall response rate was observed in 86% of patients with intraocular disease involvement, including CR in 50%. The median PFS of patients with PVRL was 23 months. After a median follow-up of 26 months, 1 CNS relapse was observed.

Assessment of the therapeutic response and follow-up

According to the International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group, the definition of ocular CR requires “no evidence of active ocular lymphoma as defined by the absence of cells in the vitreous and resolution of any previously documented retinal or optic nerve infiltrates.”95,(p5038) In practice, the response to treatment is assessed by a clinical ophthalmological evaluation,96 which aims to assess the reduction in vitreous and retinal invasion by tumor cells. However, this evaluation is subjective. The ophthalmological definitions of CR, partial response, and relapse are difficult to determine, because a measurable mass is not present. Tumor vitreous haze and retinal infiltration are observer-dependent measures. True CR is difficult to ascertain, because many patients show minimal residual disease, which is difficult to distinguish from an active infiltrate.97 Assessment of the PVRL response is a major challenge. Indeed, PVRL is currently the only aggressive lymphoma for which the assessment of a response to treatment is based on clinical evaluation, which differs substantially from the recommendation for systemic lymphoma.98

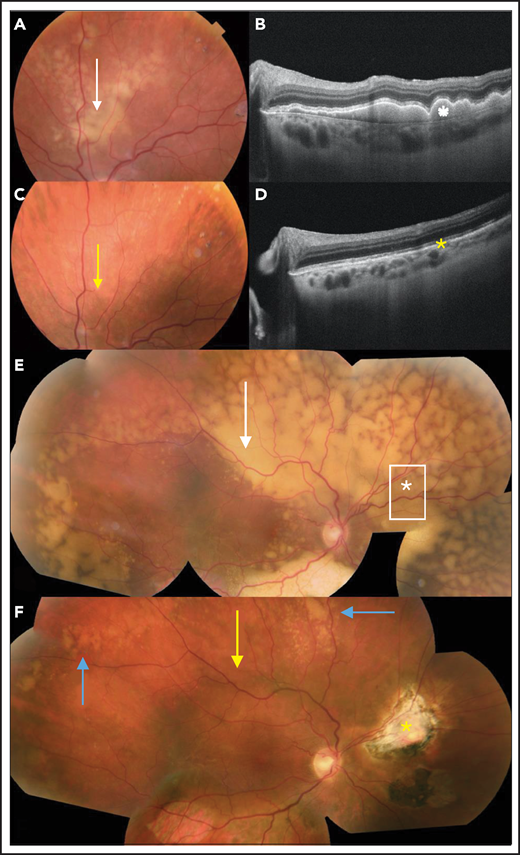

Ancillary ophthalmological examinations, such as OCT, could provide interesting noninvasive, reproducible, and comparative information about the evolution of retinal lesions (Figure 5), as evidenced by a retrospective case analysis.96 However, multimodal imaging including retinal photography, angiography, and OCT enables an assessment of the posterior pole of the eye and the retinal lesion, but not the vitreous infiltration.

Clinical evaluation of the response to treatment of PVRL. (A) Retinal photograph of a subretinal yellowish lesion corresponding to the lymphoma lesion before treatment (white arrow). (B) OCT image of the lesion described in panel A showing hyperreflective subretinal deposits (white star). (C) After systemic treatment, the subretinal lesion completely disappeared in the retinal photograph (yellow arrow). (D) In the OCT image, the subretinal deposits also disappeared (yellow asterisk). (E) In another patient, composite color fundus photograph (photographs merged together with built-in camera software) shows diffuse subretinal yellowish lesions corresponding to (sub)retinal infiltration by lymphoma cells captured before treatment (white arrow). In this patient, the vitreous was clear and free of visible lymphoma cells. The vitreous levels of IL-10 and IL-6 were low (36 and 6 pg/mL, respectively). A retinal biopsy was performed in the area of the asterisk to assess the diagnosis in this patient with pure retinal lymphoma. (F) Composite color fundus photograph (photographs merged together with built-in camera software) of patient shown in panel E after 2 courses of systemic chemotherapy (rituximab, HD MTX, procarbazine, and vincristine), showing the disappearance of most of the lesions (yellow arrow). The residual active lesions (blue arrows) disappeared after subsequent courses of chemotherapy. The scar from the retinal biopsy performed during diagnostic vitrectomy is visible on the nasal side of the optic nerve (yellow asterisk).

Clinical evaluation of the response to treatment of PVRL. (A) Retinal photograph of a subretinal yellowish lesion corresponding to the lymphoma lesion before treatment (white arrow). (B) OCT image of the lesion described in panel A showing hyperreflective subretinal deposits (white star). (C) After systemic treatment, the subretinal lesion completely disappeared in the retinal photograph (yellow arrow). (D) In the OCT image, the subretinal deposits also disappeared (yellow asterisk). (E) In another patient, composite color fundus photograph (photographs merged together with built-in camera software) shows diffuse subretinal yellowish lesions corresponding to (sub)retinal infiltration by lymphoma cells captured before treatment (white arrow). In this patient, the vitreous was clear and free of visible lymphoma cells. The vitreous levels of IL-10 and IL-6 were low (36 and 6 pg/mL, respectively). A retinal biopsy was performed in the area of the asterisk to assess the diagnosis in this patient with pure retinal lymphoma. (F) Composite color fundus photograph (photographs merged together with built-in camera software) of patient shown in panel E after 2 courses of systemic chemotherapy (rituximab, HD MTX, procarbazine, and vincristine), showing the disappearance of most of the lesions (yellow arrow). The residual active lesions (blue arrows) disappeared after subsequent courses of chemotherapy. The scar from the retinal biopsy performed during diagnostic vitrectomy is visible on the nasal side of the optic nerve (yellow asterisk).

IL-10 is a promising biomarker. Exploratory studies have shown that a decrease in IL-10 level in the aqueous humor is a minimally invasive indicator of treatment response, whereas an increase might suggest recurrence.66 This biomarker might facilitate early relapse detection.12 Prospective studies evaluating specific correlations between IL-10 level and clinical CR, PFS, or OS are lacking.

Perspectives and conclusions

In clinical practice, several therapeutic options are available, from local treatment to systemic chemotherapy and IC plus ASCT, with practices that differ between ophthalmologists and oncologists/hematologists. IVT chemotherapy, mainly MTX and rituximab, or ORT can rapidly decrease vitreous disease involvement and improve vision but will not prevent the risk of CNS relapse. Local treatment still represents a convenient symptomatic therapeutic option in patients with persistent PVRL who are unable to receive systemic treatment because of either patient characteristics and comorbidities or systemic treatment failure. Although the lack of multi-institutional prospective studies prevents unequivocal conclusions on the superiority of 1 specific therapeutic approach, our own preference is to initially provide PCNSL-like treatment with additional local ophthalmic treatment to younger patients with the objective of achieving local CR and preventing CNS relapse. Nonetheless, the best combined treatment has not yet been defined. Encouraging results have been observed with single-agent oral temozolomide, ibrutinib, and lenalidomide in patients with R/R PVRL, supporting the need to assess these drugs as first-line treatments. Myeloablative chemotherapy followed by ASCT can be offered to patients up to 65 years of age and to a subgroup of selected older patients with R/R PVRL. The risks of each therapeutic option must be considered at the time of the therapeutic decision, along with patient characteristics. The results of a prospective study with single-agent pembrolizumab in patients with PCNSL, including a cohort of patients with PVRL, are pending (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03012620). Another major challenge in PVRL is the assessment of therapeutic response. A prospective evaluation of the IL-10 level in the aqueous humor in addition to clinical and imaging ophthalmological examinations are currently the most promising feasible steps.

The diagnosis of PVRL remains challenging because of the fragility of the lymphoma cells in the vitreous, but improvement has been seen with recent advances in cytokine assays and molecular biology. International collaborative prospective studies bringing together ophthalmologists, biologists, and oncologists/hematologists are necessary to improve therapeutic outcomes and address the issue of therapeutic response criteria for PVRL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Magali Le Garff-Tavernier and Frederic Davi for fruitful discussions on the biology of PVRL.

Authorship

Contribution: C.S. was responsible for conception and design; and all authors were responsible for the provision of study materials or patients, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Carole Soussain, Institut Curie, Hématologie, 35 rue Dailly, 92210 Saint-Cloud, France; e-mail: carole.soussain@curie.fr.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.